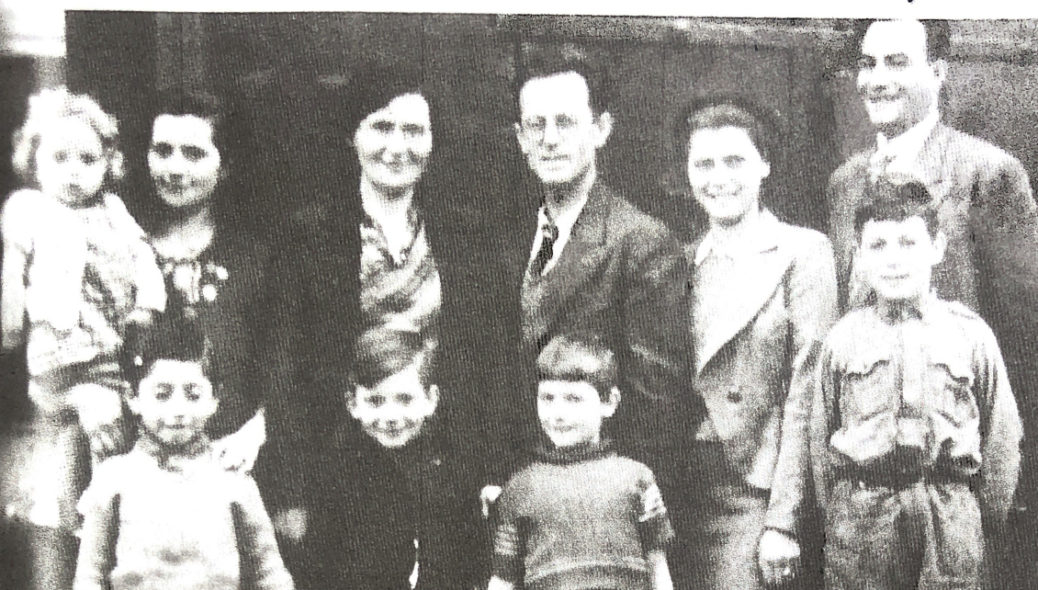

Felix Degenszajn, now 84, has been looking for answers ever since the end of the war. His questions are focused on one day in July 1944. Aged 8 at the time, he was staying at the Lucien de Hirsch private school on Avenue Secrétan, in the 19th district of Paris, which had been requisitioned by the UGIF, the Union Générale des Israélites de France, or Union of French Jews, to provide accommodation for children.

Early in the morning on July 22, the Germans arrived to round up dozens of children who they would later load into the cattle cars that made up Convoy 77, bound for Auschwitz. “I lost my memory of that time”, says Felix Degenszajn.

A child of Polish descent, Felix remembers some interesting details of life in the children’s home, where he was placed after a stay in hospital: the kitchens overlooking the courtyard and the “kids” making off with food, and the American bombers flying overhead, dropping little aluminum ribbons. “We made concertinas out of them,” he recalls. The Liberation was fast approaching.

That July 22, however, remained a black hole. “A psychiatrist explained to me that the memory loss was the result of repressed fear. I must have been panic-stricken when the Germans arrived,” he explains. During a series of raids on UGIF children’s homes that day, 242 children and 33 adults were arrested and transferred to Drancy and subsequently to Auschwitz.

The mystery of that day was revealed in the 1990s, however, when Félix Degenszajn met with a former UGIF monitor, Suzanne Schwarz. “I told her my story and gave her my name. She said, ‘I was the one who saved you’.’”

“Why me?”

This survivor who, over the years, had convinced himself that at that fateful moment he must have hidden in a cupboard under some cardboard boxes to escape the Germans, learned that this was only a “figment of his imagination” and that the reality had been quite different.

“This lady told me that she had realized that the Germans were there to round up the children and other people present. She therefore took two children, including me,” explains Félix Degenszajn. “I asked her “Why me?” and she replied that I was cute and kind and that she liked me a lot. She was 16 years old at the time.”

The trio then went to the school yard where a ladder, usually used for gymnastics classes, was kept. The supervisor set the ladder against a low wall and told the children to climb up. “We apparently climbed up and jumped over the wall and onto the street.”

Saved by a “network”

Little Felix was then dropped off at the home of a woman who ran a hotel on Avenue Secrétan. “This lady would frequently have seen us go by with the other children when we went for a walk in the park at Buttes Chaumont. Suzanne Schwarz remembered her compassionate look.”

He did not stay there long: the little boy was then passed from one person to another, being cared for by a succession of unknown members of a “network” that played a part in saving him.

“One person took me to the Jaurès metro station, and from there someone else took me by train to Tertre Doux, a hamlet in the Seine-et-Marne department. I was given a false identity card in the name of Félix Bertin, as well as two books. I remember that one of them was “Jean sans peur” (John the Fearless). I lived in a hovel, tending animals. When I was released, I weighed under 40 pounds, I had become stunted.

Once the war was over, Félix Degenszajn was reunited with his father and older brother, who until then had been hiding in Gargenville, in the Yvelines department, and did not know what had become of Félix after his stay in hospital. “My father came to pick me up from the farm, he came just like that, on his bicycle,” he recalls.

“We were profoundly affected, my family and I”

Felix Degenszajn’s mother was deported in February 1943 and murdered in Auschwitz. His aunt, his father’s sister, who was deported at the age of 32, was subjected to medical experiments at the hands of the Nazis. Her nephew explains, “Her ovaries were removed without anesthetic. After the Liberation, she came back from the camps but of course she was never able to have children.”

For his part, Félix Degenszajn is aware that he is a “miracle”. “We were all profoundly affected in my family, very profoundly affected. For me, it was due to such small things… It’s crazy that I made it through that round-up,” he still marvels. “I guess that as an adult you think about it more than as a child or teenager. All my life I’ve wondered what happened. It’s something that has been with me all along. And also, my family and I have felt a great loss. We never talked much about the past, we didn’t want to stir up painful memories, so there are a lot of things we don’t know.”

To make up for this loss, Felix Degenszajn has made numerous trips to Auschwitz and built up an extensive library. “I have a lot of books on the Holocaust that I never read. As soon as I see them, I buy them. I don’t know why I do this. Perhaps, for me, they are a memorial.”

Français

Français Polski

Polski