Zofia BORENSZTEJN 1901-1944

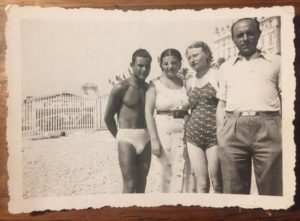

Photo of Szlama and Zofia Borensztejn, from the Lanzmann family collection

Zofia Borensztejn’s life and family background were researched by a group of three 9th grade students from the French International High School in Vilnius, Lithuania, since several documents mention that Zofia Borensztejn was born in Vilnius.

During the Covid 19 lockdown, their history and geography teacher collected together some documents available on the Internet and made contact with Zofia Borensztejn’s great-granddaughter, Doris Lanzmann, as well as some other people who had documents and testimonials concerning Zofia’s daughter, Riva Boren. At the end of the lockdown, after returning to school, the group of students worked on the dossier of information thus collected and added some historical context to the biography.

Sources:

Numerous sources had to be searched in order to provide an overall picture of Zofia Borensztejn’s life:

- the disappeared person’s file from the Defense Historical Service, Department of Veterans Affairs and War Victims, provided by the project organizers;

- an extract from the Seine Police Prefecture’s filing register, provided by the project organizers;

- the search log book from Drancy camp, available on the Shoah Memorial website;

- the civil status and census registers, available on the Paris Archives office website;

- the American Relief Mission’s December 1921 newsletter on Russia and Ukraine;

- the genealogy websites ancestry.com and familysearch.org, which provide access to numerous documents on Zofia Borensztejn’s mother and sisters, who left for the United States after the Great War, as well as on Zofia Borensztejn’s and Riva Boren’s stays in America;

- the autobiography of Jacques Lanzmann (who married Riva Boren in 1955) entitled Le Voleur de Hasards (1976);

- the autobiography of the American writer Clancy Sigal, entitled The London Lover: My Weekend that Lasted Thirty Years (2019), of which a short chapter is dedicated Riva Boren;

- Clancy Sigal’s 1956-1957 diary, several pages of which refer to his stay in Paris in 1956 and his meeting with Riva Boren. This is held at the Harry Ransom Center, the University Library in Austin, Texas, but an extract was kindly sent to us by Roberta Rubenstein, Professor of Literature at the University of Washington, author of Literary Half-Lives: Doris Lessing, Clancy Sigal, and Roman à Clef, which deals with the relationship between the writer and Riva Boren;

- the Auschwitz camp register of serial numbers;

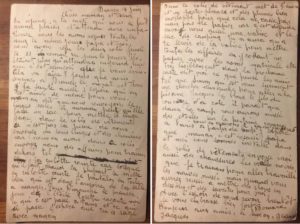

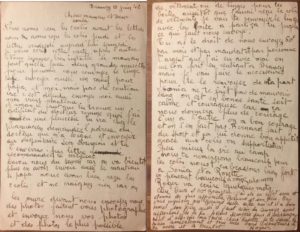

- copies of photographs and two letters sent from Drancy by Zofia Borensztejn’s husband and son in 1942, generously sent to us by Riva Boren’s granddaughter and Zofia Borensztejn’s great-granddaughter, Doris Lanzmann;

- testimonials from people who knew Riva Boren, thanks to the assistance of Laurence d’Ist, art historian.

Ukrainian Origins

Zofia Borensztejn was not in fact born in Vilnius but rather in Wolynsk, Ukraine, then in the Russian Empire, on March 4, 1901, under the maiden name Mandell/Mandelöl. This is what most of the French documents that we consulted state, despite some confusion at times between Wolynsk and Wolno/Wilno/Vilnius in Lithuania. We had no access to birth registers that could confirm this, but the Ukrainian origin is not in doubt given the number of documents found on the Mandell family on genealogy sites.

Zofia’s father’s name was Israël and he may have been a merchant. Her mother’s name was Mechlia/Mahlia. Zofia had three sisters: the eldest, Ita, was born around 1900, Mala was born on December 5, 1903 and Estera on June 1, 1905. In their naturalization records in the United States, the last two, who became Molly and Esther, claim to have been born in Zhitomir, in Volhynia, which is in the same region as Wolynsk, but they do not appear in the city’s Jewish birth records. It is likely, however, that the Mandell family lived there for some time. A family photograph that appears to date from the end of the First World War gives the impression of a rather well-off family.

The Mandell family, photograph from the Lanzmann family collection: Zofia is in the center, standing.

The escape

The once well-to-do family can be found in 1921, destitute and in mourning, the father having died, in a refugee camp in Rovno, which was still in Volhynia, but in a part of it that had by then become Polish. The JDC (the American Jew Joint Distribution Committee, founded in 1914 to help Jews all over the world) holds a record of a transfer of 300 dollars to Mahlia Mandell and her daughters in the camp, so that they could take the boat to the United States. This money had been sent by a relative, Morris Mandell, who had emigrated earlier.

The Mandell family was fleeing a turbulent situation: Ukraine had declared itself independent in 1917, but it was fighting against the Red Army (which eventually took control of the country in 1919-1920), as well as against the Polish army for control of border areas such as Volhynia. Pogroms were carried out by soldiers of all the armed forces involved, but it was Ukrainian soldiers, who accused the Jews of being supporters of the “reds”, who carried out the bloodiest massacres on an unprecedented scale: there were at least 35,000-50,000 deaths in Ukraine in 1918-1920, perhaps as many as 100,000, the pogroms having begun in Volhynia, where the Mandell family lived. In Zhitomir alone, several hundred people were killed in 1919. Was Israël killed during one of the pogroms? He is not included on any of the lists of victims, but the lists are not exhaustive.

According to reports by the JDC, the massacres prompted many Jews to flee, with some families hiding for weeks in the wilderness to escape the armed gangs. When the Polish army took over most of Western Volhynia, including Rovno, the JDC reports mention dozens of looted towns and villages, a Jewish population in abject poverty, and thousands of widows and orphans, such as the Mandell family.

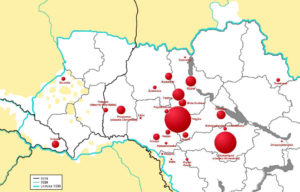

The 1918-1920 pogroms in Ukraine, by Wojciech Winkler, CC0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24946771

The Red Army’s takeover of Ukraine and the implementation of Bolshevik policies, such as the nationalization of companies, dealt the final blow, at least to wealthy families such as the Mandells. Thus, according to the American Relief Mission, the Rovno refugee camp was populated not only by Jews, but by members of the “intelligentsia”, the educated middle class, who fled the Bolshevik occupation of the Ukraine, at which time Rovno came under Polish control. Thousands of Jewish refugees and members of the “intelligentsia” were crowded into the camp, often in tents, suffering from hunger, exhaustion and disease, despite help from the Polish authorities.

Photographs of refugees in Rovno, from the JDC archives

A new life

With the money received from America, Mahlia and her daughters Estera and Mala set sail from Hamburg for the United States on May 30, 1922 and arrived in New York harbor on June 9. They were met by their relative, Morris Mandell, and moved to Boston, where Ita, the elder sister, joined them later. Until at least 1930, they lived in Boston, before moving to Manhattan, in New York City. Ita, who by this time was known as Edith, got married but was widowed soon afterwards, while her two sisters stayed with their mother until her death in 1948.

Zofia Mandell, however, did not go with them. She stayed behind and married a Warsaw man, Szlama Borensztejn. There are two possible explanations for their meeting: either Szlama visited the Rovno camp, perhaps on behalf of a Jewish aid organization, or Zofia and no doubt her sister Ita, before she went to the United States, left the refugee camp and went to Warsaw to look for work.

Pendant with photos of the Borensztejn couple, kept Riva Boren and now the Lanzmann family

In any case, Zofia and Szlama Borensztejn, once married, left for France at the beginning of the 1920s, as part of a mass exodus during the inter-war period, which included several Borensztejns from Warsaw: an exodus to the “City of Light, a city whose dazzling signs had attracted those fleeing “l’Europe de ténébres”, or “Europe of darkness”, as Jacques Lanzmann called it in his 1976 book Le Voleur de Hasards (The Thief of Chances) about Zofia Borensztejn’s family. A “Europe of darkness”, marked by anti-Jewish violence, including that in Poland, in Warsaw.

In Paris, Zofia and Szlama had two children: Bernard, who was born on September 28, 1923, when his parents were living the suburbs, at 59, allée des Aldes in Pavillons-sous-Bois, and then Riva, born on August 13, 1926, by which time the family had moved to Paris and lived at 10 rue du Pressoir, in the 20th district of the city. On 2 February 1929, Zofia and Szlama “remarried” at the Town Hall of the 20th district, in order for their union to be legally recognized by the French authorities. As from 1931, the family was registered at 130, rue Saint-Denis, in the 2nd district, but without Riva, who had possibly been sent to the countryside for a while for health reasons.

The Borensztejns, immigrants who probably had limited means to begin with, did not settle in the most exclusive of neighborhoods. The rue Saint-Denis is notorious for prostitution on its sidewalks. This did not stop the family from starting a business, however. Szlama was an embroidery merchant and Zofia was a seamstress, and, according to reports about their daughter Riva, they had a sewing workshop called the “Atelier de couture d’Odessa”, the “Odessa Sewing Workshop”. A tribute, no doubt, to Zofia’s Ukrainian roots, the port of Odessa having a greater appeal to customers than Zhitomir or Wolynsk. The photographs sent to us by Zofia’s great-granddaughter portray a rather well-to-do family that could afford a holiday by the sea. In addition, Zofia Borensztejn travelled to the United States at least twice to visit her family, in 1929 with her children, and again in 1939. We also know from Jacques Lanzmann’s memoirs that after the war Riva wanted to write a book about Beethoven, dedicated to her father Szlama: we can therefore surmise that he had a taste for classical music, and perhaps a gramophone at home.

Zofia Borensztejn (in the white dress) with her loved ones at the beach, in the thirties. Photograph from the Lanzmann family collection.

In addition, census data and letters written by Bernard from Drancy in 1944 reveal French forms of first names and the use of the French language: Zofia became Sonia, Szlama became Salomon or Michel, and Riva was Rosette. There appears to have been a clear desire to integrate into French society: in 1932, Zofia Borensztejn was naturalized as a French citizen, by a decree dated 12 January, probably at the same time as her husband.

A family torn apart

Despite this desire to integrate, the family was badly affected by anti-Jewish persecution under the Vichy regime and the Occupying army. Szlama and Bernard were arrested and deported in 1942, on Convoy 3 to Auschwitz on June 22, at a time when the police only rounded up the men. It was not until the Vel-d’Hiv round-up on July 16 and 17, 1942 that the round-ups were extended to include women and children.

On June 13, from Drancy, Bernard and Szlama each wrote letters to “Sonia” and “Rosette”, asking for clothes, a penknife, soap, and “some photos, have them take pictures of you and send us your photos and pictures, as many as possible”. Szlama tried to reassure his wife: “Sonia, don’t worry, we are healthy, be calm and brave, because it will give us more courage and we are not [worried]. Bernard does some exercise and it gives him a good appetite.” Bernard confirmed that he was “in good spirits and in good health too.” One of Bernard’s friends, Roger, who he met up with in Drancy, added: “Don’t worry, Bernard stays beside me and he’s in good spirits, and his father is too. We must have courage, we’re nearing the end.”

Letters from Drancy, held by the Lanzmann family

Both Bernard and Szlama were both given identity numbers at Auschwitz, which means that they would have been tattooed upon arrival and subjected to forced labor, so not gassed immediately. Nevertheless, they both died in August 1942, Bernard on the 3rd and Szlama on the 11th. On the Convoy 3 list, Bernard is listed as a “bookkeeper” and his father only as a “travelling salesman”, which would suggest that his workshop had been looted, or “Aryanized”.

Zofia and Riva, meanwhile, were subjected to a double drama, as the men’s arrest took place at the very moment when the wearing of the yellow star became compulsory, on Sunday June 7, 1942. Bernard mentioned this in his letter to Riva, sent from Drancy: “On Sunday, the first day of the star, Rosette, tell me what happened in Paris and what is happening now. I hope you’re good to Mommy.” This second aspect, the wearing of the star, was so traumatic that Riva Borensztejn kept hers all her life.

Riva Boren’s yellow star, held by the Lanzmann family

Zofia was arrested two years later, on the morning of July 27th. On the 28th, she was sent to Drancy, where the search book states that she had 143 francs on her. This was a modest amount compared to other deportees (one franc in 1944 would be worth 20 cents today).

On July 31, Zofia was sent to Auschwitz on Convoy 77. The French Official Journal of 19 May 2019 gives August 5 as the date of her death, but this is an arbitrary date. The authorities chose to use the 5th day after the departure of the convoy as the date of death of all deportees if there are no documents to prove otherwise. In fact, the majority of the deportees were sent to the gas chambers as soon as they arrived, on August 3.

The mystery of Riva Borensztejn

Only the daughter, Riva, survived the Holocaust. Thanks to the autobiographical works of her future husband, Jacques Lanzmann, and the American writer Clancy Sigal, as well as his typewritten diary, we know that Riva Borensztejn went into hiding to escape arrest and to stay alive. Riva took refuge in various attics and toilets, and then joined a “gang” of young street girls, who played a part in the Liberation of Paris. Riva, while carrying some ammunition, reportedly escaped the machine-gun fire by hiding under a broken-down tank.

But when did Riva go into hiding? According to Jacques Lanzmann and Clancy Sigal, it was at the time of the arrest “of her parents” when she was fourteen years old, whereas in fact her parents were not both arrested at the same time, and Riva was sixteen in 1942 and eighteen in 1944. But both writers refer to a fairly long period of living a clandestine life, which suggests that Riva went into hiding long before her mother’s arrest: Clancy Sigal mentions the year 1943.

In fact, according to the accounts of several people who knew her, Riva and her mother had quarreled because Zofia wanted to be arrested so that she could be reunited with her husband and in particular her son Bernard, whom she adored. Zofia reportedly took risks in order to be noticed by the police, and Riva then felt in danger, so left the family home. Nevertheless, other accounts mention an ongoing relationship between mother and daughter that continued until Zofia was arrested. Zofia is said to have accompanied Riva to a bus stop on the morning of July 27, 1944, because she had to go into hospital. When she came out, Riva reportedly watched from afar, hidden in a park, and witnessed her mother’s arrest.

Riva Boren after the war: “the undead past”

After the war, Riva joined her aunts and grandmother in New York in 1946. According to Clancy Sigal, she worked as a singer in night clubs and as a model for fashion photographers. She also began to study Fine Arts there.

In 1949, Riva returned to Paris to continue her studies at the Grande Chaumière Academy, but returned to New York in 1951 to marry a fellow student at the academy, the American painter Eugen Roy Witten. The marriage did not last long, however, and in 1952, Riva returned to France. She became an artist under the name Riva Boren, working in the sculptor Ossip Zedkine’s studio before becoming a painter. Riva Boren mixed in artistic circles in Montparnasse, where she met Jacques Lanzmann, whom she married in 1955.

Riva Borensztejn as a Fine Arts student in Paris, photograph from the Lanzmann family collection

Jacques Lanzmann was a writer, journalist and future lyricist of the singer Jacques Dutronc. He owed much of his literary success to Simone de Beauvoir, the great existentialist writer and feminist, author of The Second Sex. Incidentally, Simone de Beauvoir allowed Jacques and Riva Lanzmann to live in her former apartment at 11, rue de la Bûcherie.

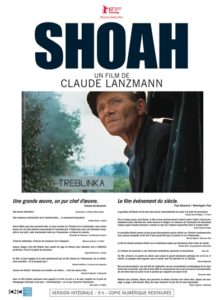

Simone de Beauvoir was in a relationship with Jean-Paul Sartre, the great philosopher of existentialism, human freedom and commitment, and they became an iconic couple. Riva and Jacques Lanzmann were both active in the Communist Party and took part in the demonstrations against the Algerian war. Jacques’ brother, Claude Lanzmann, later directed “Shoah” the epic ten-hour documentary about the Holocaust, in 1976-1981. It was this piece that brought together numerous eyewitness accounts and photographs taken at places where the genocide took place (without using period images), which made the word “Shoah” synonymous with “Holocaust” or “Final Solution”.

Riva and Jacques Lanzmann had a son, but only stayed together for two years.

Both Jacques Lanzmann and Clancy Sigal remember Riva Boren at that time as an extremely beautiful young woman, who made a strong impression but was deeply traumatized by the deportation of her family. Jacques Lanzmann described her as “wounded to death and bereaved forever” while for Clancy Sigal she was the embodiment of the “undead past”. In his 2016 book, A London Lover: My Weekend that Lasted Thirty Years, he wrote “France’s années noires never ended for her”.

However, later on, Riva Boren was deeply marked by a trip to Asia, in particular Nepal, in 1972, where she met some Tibetan refugees and found herself wandering among them. This trip greatly influenced her work, causing her to abandon canvas for kraft paper and pastels. The figures depicted in her work were often faceless, nostalgic, as if keeping a secret, inviting observers to embark on a spiritual journey into the depths their soul.

Riva Boren died in 1995.

Contributor(s)

Three 9th grade students from the French International high school in Vilnius, Lithuania, under the guidance of their teacher, Yvan Leclère.

Français

Français Polski

Polski