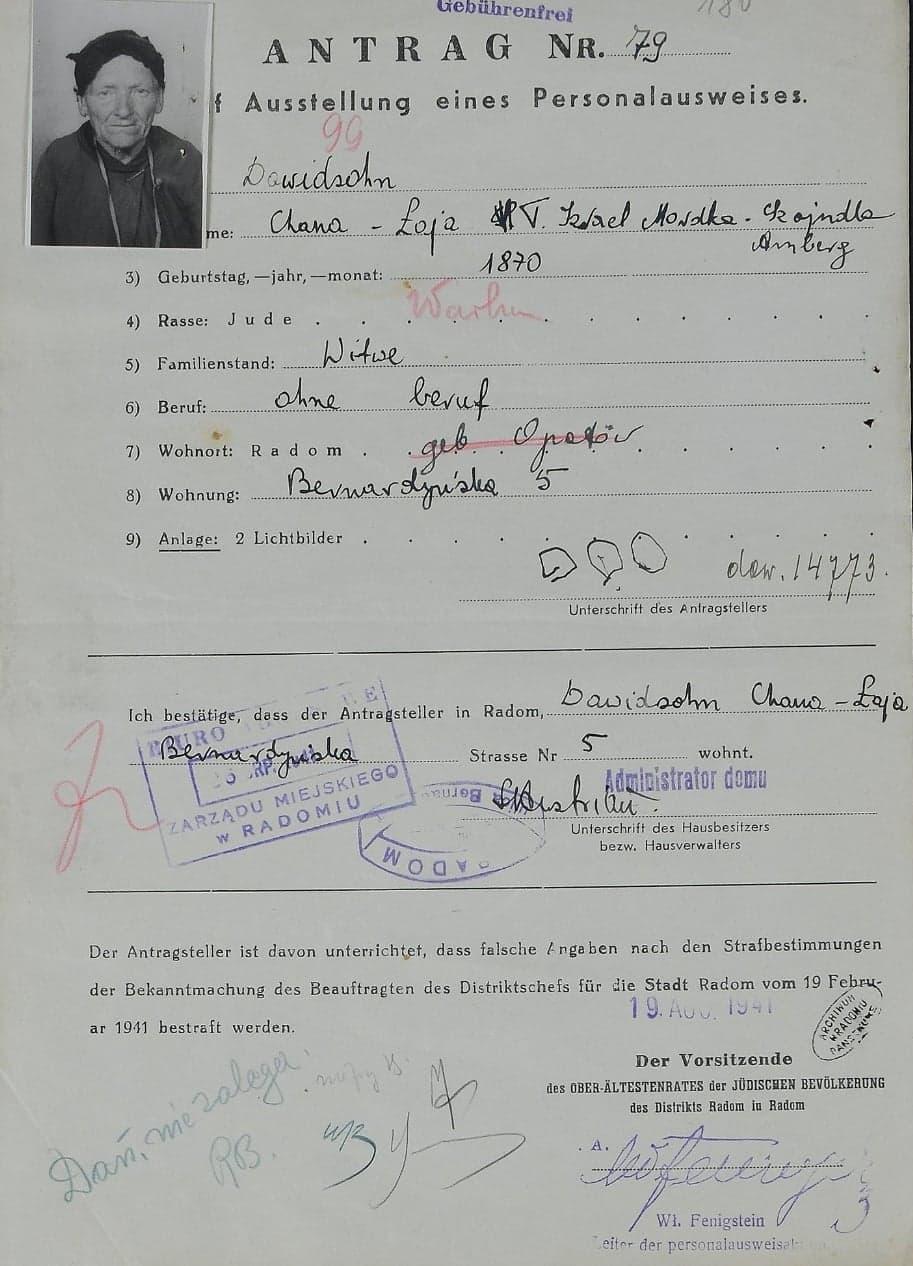

Zlata WALDBERG-DAWIDZON

Our names are Anna, Kaja, Judyta, Kacper and Katarzyna. We are students in the literature stream at the Lyceum Międzynarodowego Liceum “Paderewski” High School in Lublin, Poland. Our history teacher, Anna Nadolska, encouraged us to participate in the “Convoy 77” project.

History of the Jews in Lublin

The history of the city of Lublin, which has been home to a Jewish minority for centuries, is closely linked to this community. Over time, the city has become a symbol of the rise of Hebrew culture and Orthodox Judaism. This is why it has often been called the “Jewish Oxford” or the “Jerusalem of the Kingdom of Poland”. From the end of the 19th century onwards, the Jews themselves began to see themselves as a minority community on a national scale, rather than as an isolated group belonging to a different religion. From then on, they became an active part of the Lublin society. The first Jewish schools were opened, as well as many other facilities serving the Jewish population, including the fully equipped hospital on Lubartowska Street and the orphanage on Grodzka Street. However, Jewish culture did not really take off in Lublin until 1915, when the city came under Austro-Hungarian rule. The invaders’ benevolent attitude encouraged Jewish involvement in the local community and, as a result, in 1916 the first Jewish monthly magazine in Polish, Myśl Żydowska (Jewish Thought), was published. A number of cultural institutions were also founded, such as Jakub Waksman’s amateur theater and the first public library. In addition, 15 private Jewish schools operated in the city and Jews began to participate actively in the deliberations of the City Council. In 1931, the Jewish population of Lublin already numbered 38,935 and their cultural development was in full swing. New sports, cultural and educational centers were created, headed by the prestigious and modern Yechiva Chachmei Lublin Rabbinical School, opened in 1930 on the initiative of Rabbi Meïr Shapiro. At the time, there were nine Jewish political parties in Lublin, offering young people the opportunity to become involved in social life. The Jewish press also flourished, with the addition of two new Yiddish-language publications: the Lubliner Tugblat (Lublin Diary) and the weekly Lubliner Sztyme (Voice of Lublin). Young people increasingly aspired to assimilate into the Polish community, making their culture an integral part of our city’s history.

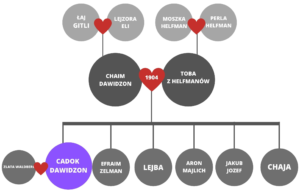

- Family tree

Zlata’s family tree, which we reconstructed from archived documents.

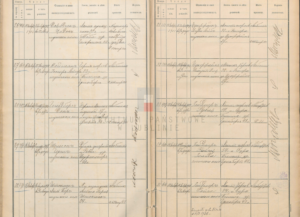

2. Birth certificate

Thanks to the generous assistance of the archivist, we were able to find Zlata Waldberg’s birth certificate as part of archive no. 1753.

Through our work on the project, we were able to obtain information about the rules and customs of the Jewish community, for example that the registration of Jews’ marital status was a two-step process. First, the rabbi performed religious ceremony and registration, and then clerk at the town hall registered the marriage officially.

It was the year 1914, in spring, when flowers were in bloom everywhere. It was the 2nd or the 15th of April. Before the First World War the Kingdom of Poland used two calendars, Julian and Gregorian, in its official documents, hence the 12-day difference. In a house at 101, Grodzka Street, a child was born, a girl called Zlata, named after her maternal grandmother. The street no longer exists today under the same name, but if we continue towards the Grodzka Gate, we can still find a building on the corner near 2 Zamkowa Street, which is probably the same one.

3. Parents

Zlata’s parents were Waldberg Symcha and Sura Ita Wegsztajn.

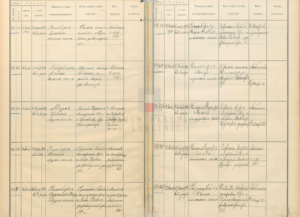

We were able to find the birth certificate of Symcha Waldberg (P.J. No. 4). He was born on August 12/24, 1882, in house No. 551. His parents were Icek and Estera Micenmacher. We also managed to obtain their marriage certificate: they got married on August 20 / September 1, 1881 (Attachment No 8). Sura’s parents were called Icek and Zlatta Band. Zlata’s father was a hatter.

4. Schooling

Unfortunately, we were unable to find out anything about Zlata’s education because Jewish school records no longer exist. We had hoped to learn something from the records from Lublin’s public schools, but they were sent to the archives department in very poor shape. Among other things, the daily roll call registers and class lists were missing. The chances of retrieving such information were therefore negligible.

5. Marriage certificate

The exact date is unknown, but the marriage probably took place in the years 1930-1936. Two young people in love, Zlata Waldberg and Cadok Dawidzon, got married. It is possible that they did not declare their relationship, which was a common occurrence in the Jewish community, or that they got married in France, because all trace of the marriage certificate seems to have been lost.

6. Population registers

Unfortunately, Lublin’s pre-war population registers, which were called “books of the permanent population”, no longer exist. They were destroyed during the bombing of the city during the Second World War. In the archives we find only partially salvaged registers from the 19th century, opened in the years 1839-1840 and in 1865, where the inhabitants of Lublin were registered until about 1890.

Icek Wolberg, Zlata’s grandfather, who was a shoemaker, lived in house No. 454.

In the 19th century, a house numbering system, where houses were assigned a “Police Number”, was introduced. According to the new numbering system, it became 27, Ruska Street.

7. Departure for France

We consulted records of passports issued in the years 1925-1929 and 1932-1939 (records for the years 1930-1931 are missing), as well as passport applications, few of which were kept.

We found neither Zlata nor her husband in them. They may have left before 1925 or in the years 1930-31.

8. Life in France

Information about Zlata’s life in France was gathered by students of the René Goscinny French High School in Warsaw. Additional information about the arrest of Zlata and her husband was provided by Mr. Serge Jacubert.

Before the war, Zlata lived with Cadok in the city of Lyon, where Cadok rented an apartment from 1937 to 1944 at 28, rue de l’Annonciade (P.J. 5 and 6). It appears therefore that Cadok left for France before 1937. Zlata was a shopkeeper, buying and selling various small items. This was not her only occupation, however, as she also worked as a typist.

On June 22, 1944, the couple heard someone knocking on the door of their modest apartment in Lyon. Gestapo agents entered their building in search of conspirators or resistance members working against the German occupiers. They were Rywka Skorka, whose French name was Régine Jacubert, and her brother, Yerme Skorka.

According to the information in their possession, there should have been a conspirator present in the building where the Dawidzons lived. The Germans searched the entire apartment building, but they found nothing and no one connected to the Resistance. However, this did not prevent Zlata and Cadok from being arrested, even though there were no pending legal proceedings against them at the time. The couple was separated, and Zlata was interned at Fort Montluel on June 22, 1944, then held at Drancy from June 30 to July 31, 1944, when she was deported. On August 3, 1944, she arrived at Auschwitz, where she remained until the end of October 1944. The last place in which she was detained was Kratzau, where she remained for another six months until May 11, 1945. On that day, the camp was liberated and, together with some other prisoners, she was released. Zlata Dawidzon had managed to survive in the concentration camps. She then decided to return to France. Some after the war, in 1951, she applied for the status of political internee. The answer was a long time coming. She did not receive confirmation of her status until three years later, on March 20, 1954. Then, on August 2, 1954, she received an allowance based on the status having been granted. From the reply to the Director of Litigation, Civil Status and Research by the Interdepartmental Director of Veterans and Victims of War, dated April 1953, we learn that Zlata had been arrested because she was a Jew. In 1973, in accordance with the law at that time, Zlata received compensation from the Federal Republic of Germany. After the war, Zlata and Cadok settled in Paris, at 32 rue Blancs-Manteaux, in the 4th district.

Attachment No 2 – Town plan of Lublin, dated 1912

Attachment No 3 – The Rabbi’s book, showing the record of Zlata’s birth

Attachment No 4 – Birth record of Symcha Waldberg, Zlata’s father, in the Rabbi’s book of 1882

Attachment No 5 – The building at 28, rue de l’Annonciade, where Zlata Dawidzon and her husband lived and were arrested.

Attachment No 6 – The building at 28, rue de l’Annonciade

Attachment No 7 – The “book of permanent population”

Attachment No 8 – Marriage certificate of Zlata’s grandparents on the paternal side, Icek and Estera-Zlata..

Contributor(s)

Anna, Kaja, Judyta, Kacper et Katarzyna de la filière littéraire au Lycée Międzynarodowego Liceum « Paderewski » à Lublin, sous la direction de l’enseignante d’histoire, Anna Nadolska.

Français

Français Polski

Polski