Yaich TIMSIT, 1905 – 1944

We are a class of 9th grade class at the International School of Casablanca, in Morocco. We and our teacher, Ms. Zriwil, first heard about the Convoy 77 project in February 2020. We found the idea of the project interesting: we were to tell the story of Yaich Timsit, a Jewish man from Morocco who was deported to Auschwitz on the last large convoy, in July 1944.

This project required us to take on the role of investigators. We also had to work around the current health situation. Thanks to the help of the French National Office for Veterans and Victims of War, we had access to various historical documents that helped us in the creation of this biography. But we needed more… We therefore sought to contact Yaich’s family, and we found them. We also contacted Mr. Farid El Asri, anthropologist and Doctor in Political and Social Sciences at the Catholic University of Louvain, Belgium (ULC), Associate Professor at Sciences Po Rabat, Morocco (UIR) and Associate Researcher at the CNRS, the French National Center for Scientific Research; and Mr. Michel Boyer, Doctor in History of International Relations and former Senior Officer, Associate Professor at Sciences Po Rabat (UIR).

This was all a great adventure for us, which ended with the making of a short film. Here is Yaich Timsit’s life story.

On Sunday, April 23, 1905, in Mogador (now Essaouira), in Morocco some wonderful news filled the hearts of the Timsits: the arrival in the world of their son Yaich, יאִשׁ, يعيش. This is an Israeli first name whose Arabic meaning means “to be alive”. The name held such a powerful, iconic meaning for us. That’s what prompted us to become “passers-on of history”: by honoring Yaich’s memory, we hope to bring out the real meaning of his first name.

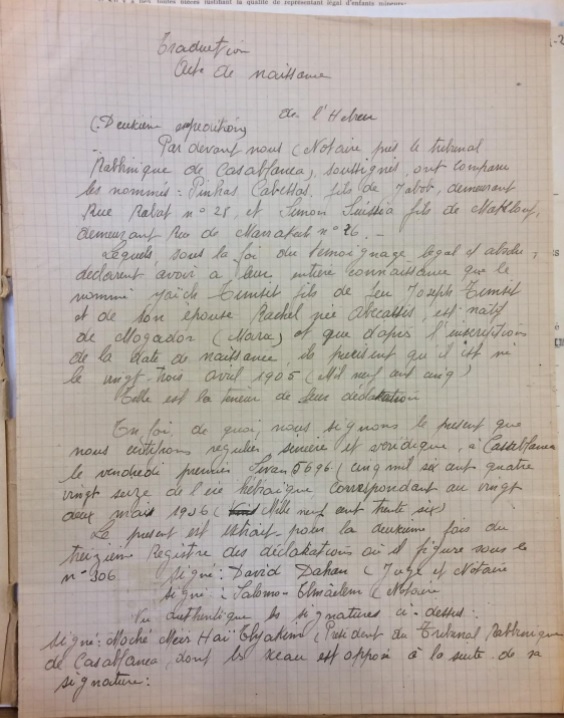

Yaich Timsit’s birth record

Since we could not travel to Essaouira, we tried to contact the Jewish museum of Essaouira, Bayt Dakira, but to no avail. We were therefore most interested in a documentary about the history of Essaouira, which provided us with some valuable information about Yaich’s background.

He was the son of Joseph Timsit, a merchant in Mogador, and Rachel Timsit, née Abecassis. They lived in harmony with the Muslim community. They lived in the Mellah, a neighborhood exclusively reserved for Moroccans of the Jewish faith. Yaich went to the Alliance Israélite Universelle school, as did the other children of the same religion.

Rue du Mellah, Mogador (Essaouira)

In the 1910s, Yaich and left Morocco for the first time and travelled with his parents to France. At that time, there were more than 15,000 Moroccan workers in France.

In 1914, when he was only 9 years old, the First World War began. It was a war of annihilation, in which women played an important role, as they replaced men in the factories. His father continued to work as a laborer and did not serve in the war.

Meanwhile, Yaich grew up and pursued his childhood dreams. He hoped for a more prosperous future. He became an accomplished and distinguished young man. It was then that he met Hassiba Alice Suissa, a young Moroccan woman, also a Jew and a native of Mogador. He fell in love with her and saw himself building a future with her.

Photo of Yaich Timsit

On March 15, 1933, at the age of 28, he married the love of his life at the Synagogue in Casablanca, where they vowed to stay together and to respect each other forever, for better or for worse. The young couple went to live in the Mellah district of Casablanca, where they lived for a time at 30, rue Worthington, now rue Mohammed Tabit.

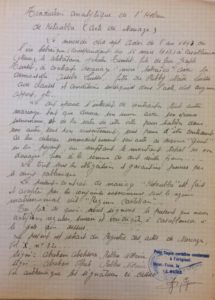

Yaich Timsit and Hassiba Alice Suissa’s marriage record

The crash of 1929 caused the Moroccan economy to collapse. Many people decided to emigrate to countries where the situation was more stable. Between the wars, on the other side of the Mediterranean, France was in the midst of emancipation: the Matignon agreements allowed for wage increases, ensured freedom of association, and established collective agreements. The working week was reduced from 48 to 40 hours, and employees were guaranteed two weeks paid vacation.

As a result, Yaich Timsit decided to return to France. He felt that a better future awaited them in that part of the world. His dream would soon come true, as he would go to work at the Saint-Gobain Glass and Chemicals Factory in Saint-Fons, near Lyon in the Rhône area of France, where he had previously worked as a mechanic.

Yaich Timsit – first row on the right, squatting (1940), while employed at the Saint Gobain factory in Saint Fons

It was there that Yaich and his wife, Alice, started their family, which was made up of Joseph, their eldest child, born May 27, 1934, Henri, born October 22, 1936, and Simon, born January 20, 1941.

Yaich Timsit – back row, 4th from the left, at the marriage of his niece in 1943

On September 1, 1939, the world went to war again. It was the beginning of a global ideological conflict.

In 1940, France was attacked by Nazi Germany and defeat was swift. There was widespread panic, which caused a mass exodus of people to the south of France, where they hoped to escape from the advancing German troops.

The government lost, and Marshal Pétain came to power. He thus became President and put an end to the Third Republic, forming what was known as the Vichy regime. He then asked the Germans for an armistice and as a result, France was divided in two. The north and the west of the country made up the area occupied by the Germans, while the south was known as a free zone. A demarcation line separated the two zones.

In the Rhône area, Lyon was the center of the Jewish Resistance movement. Yaich continued to work at the factory. He remained confident that he would not become a victim of the war. However, increasing numbers of people were arrested, tortured and deported and in July 1944, the situation became worse than ever.

It was a Wednesday afternoon, June 7, 1944 when Yaich, who was by now 39 years old, had just finished a long day at work and was looking forward to going home to his family. However, the Germans stopped him on the way, arrested him and transferred him to Drancy camp.

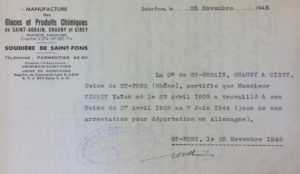

Yaich Timsit’s work report, which mentions the “day of his arrest for deportation to Germany”.

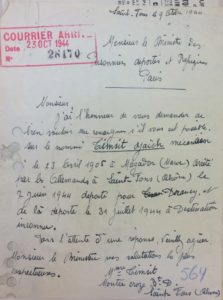

Having no news of her husband, Alice sent a letter to the Minister of Deported Prisoners and Refugees in Paris on October 9, 1944:

Alice Timsit’s letter to the Minister of Deported Prisoners and Refugees, in Paris (1944).

What she did not know, as she wrote this letter, was that Alois Brunner, the commander of the Drancy camp, had already organized the last of the large convoys to Auschwitz. Convoy 77 left Drancy on July 31, 1944, carrying 986 men and women and 324 children. Yaich’s death warrant was issued there and then.

Extract from the list of Convoy 77 deportees

Something else she didn’t know about was the horror he experienced on that convoy. First of all, the cattle cars, in which they were all piled up like corpses, even though they were alive. Yaich was tattooed, beaten, threatened, and then murdered. And yet, the Dachau song rang round:

“Charged with death, high tension wire

Rings around our world a chain.

Pitiless a sky sends fire,

Biting frost and drenching rain.

Far from us is lust for living,

Far our women and our town

When we mutely march to toiling

Thousands into morning’s dawn.

But we all learned the motto of Dachau to heed

And became as hardened as stone

Stay humane, Dachau mate,

And work as hard as you can, Dachau mate,

For work leads to freedom alone!

Faced by ever-threatening rifles

We exist by night and day.

Life itself this hell-hole stifles

Worse than any words can say.

Days and weeks, we leave unnumbered

Some forget the count of years

And their spirit is encumbered

With their faces scarred by fear.

But we all learned the motto of Dachau…

Lift the stone and drag the wagon

Shun no burden and no chore

Who you were in days long bygone?

Here you are not anymore.

Stab the earth and bury depthless

All the pity you can feel,

And within your own sweat, hapless

you convert to stone and steel.

But we all learned the motto of Dachau…

Once will sound the siren’s wailing

Summons to the last roll-call.

Outside then we will be hailing

Dachau mates uniting all.

Freedom brightly will be shining,

For the hard forged brotherhood

And the work we are designing

Our work it will be good.

For we all learned the motto of Dachau…

(Translator’s note. This is a slightly edited English translation of the original lyrics of the Dachaulied, as they appear in Paul Cummins’ biography of Herbert Zipper. The poem was originally written by Jura Soyfer and Herbert Zipper wrote the music. The two men had been friends in Vienna in the 1930s, and in the summer of 1938, they again met up in Dachau, where they wrote the song. Soon afterwards, they were transferred to the Buchenwald camp)

We tried to comprehend what Yaich Timsit went through, but it was beyond anything we had ever known… We were also interested in the testimonies of former deportees who survived, including that of Henri Kichka, who said that: “The worst thing was the food, when there was any … dry bread and soup. We were dying, we were garbage, I was half way to becoming a cadaver.”

Alice never got to say goodbye to her husband. All she had was a letter, telling her of her husband’s death.

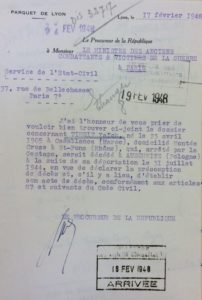

Reply from the Minister of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees, in Paris (1948)

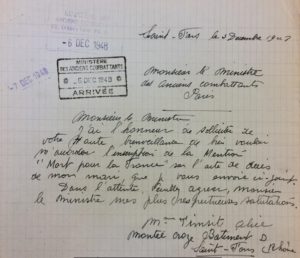

In order to honor her late husband, Habiba Alice Timsit sent another letter to the Minister of Veterans Affairs in Paris on Monday, December 6, 1948. She asked for her husband to be granted the status of “Died for France”.

Alice Timsit’s letter to the Minister of Veterans Affairs (Paris) – 1948

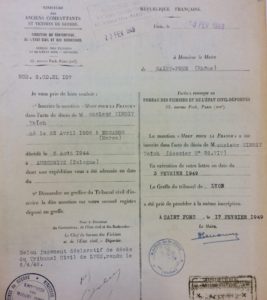

Her request must have been granted, since the words were later inscribed on Yaich Timsit’s death certificate.

Inscription of the words “Died for France” on Yaich Timsit’s death certificate – February 3, 1949

Elie Wiesel said “All peoples who do not know their history are called upon to relive it”. Thanks to you Yaich, we have a memory of the past and also a vision of the future.

Français

Français Polski

Polski