Suzanne BORUCKI, 1926 – 1991

This biography was produced by the students of the “Memories of the Shoah” club at the Robert Desnos junior high school in Rives, in the Isère department of France, and their teachers, Cécilia Pommier, Katia Verhoeven and Joan Trech.

Portrait of Suzanne, 1947

In order to reconstruct the life of Sarah Borucki (whose real name was Suzanne), we had to turn to various different sources (official documents, birth certificates, deportation certificates etc.) and we were particularly moved by two of them: We were lucky enough to meet Mr Antonin Jaquier, the son of the Borucki family’s neighbours, who was 14 at the time they sought refuge in Isère, and to find Suzanne’s granddaughter, Claire, who put us in touch with her father, Suzanne’s son, Jean Michel Habergrytz, who shared his memories of his mother with us. We thank them very much for the trust they placed in us. The memory of Suzanne will stay with us for many years to come.

Life before the war

The Borucki family originated from Warsaw, in Poland.

Symcha Joseph Borucki, Sarah’s father, was born in 1899 in Kiev. Her mother, Alta Laye Borucki, née Trafikant, was born in 1896.

When Poland became independent again in 1918, some 3,500,000 Jews were among its citizens, i.e. 10% of the population within the borders as they were in 1921. Anti-Semitism, however, was a political problem as the country developed. Between 1917 and 1922, between 100,000 and 150,000 Jews were killed and their property looted in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Poland. This was the beginning of the persecution of Jews. These pogroms in the 1920s paved the way for the Holocaust.

Symcha and Alta had their first child, Dina, on September 14, 1920, in Warsaw. Then came a boy, Pejeth Peysach, on April 2, 1922. Later on, in France, he would be called Paul.

It was after the birth of their second child that the Boruckis decided to leave Poland, as did many of their fellow citizens. At that time, many Jews saw France as a haven of peace. There was even a Jewish saying that went “Happy as a Jew in France!”.

They followed in the footsteps of many other members of the Trafikant family, including Alta’s father, who was staying in the Jewish quarter of Rue des Rosiers in Paris, having fled from the prevailing anti-Semitism in Poland.

Suzanne was born on November 3, 1926 in Paris. At the time of her birth, Joseph was 27 years old and Alta was 30. Paul was 4 years old when his sister was born and life was easy in those days. Nazism had not yet taken hold in Germany, although Hitler attempted a coup d’état, also known as the “Brewery putsch”, on 8 November 1923, the year after Paul was born

The family lived at 14, rue Villiot in the 12th district of Paris. Joseph and Alta were retailers and worked in the clothing trade. They got married on February 24, 1927 in Paris, when Suzanne was three months old. There must have been a religious ceremony, but there is no record of it. In 1931, the family left rue Villiot to live at 214, rue Saint Maur in the 10th district, and then in 1936 they moved to 38, rue Meslay, in the 3rd district.

Suzanne as a teenager

Dina and her father, Symcha Joseph, in 1938

Joseph, Dina and Alta in 1938

Dina, who had married and had children, left Paris for the Gers department of France in 1941. In 1939, the Second World War had begun. In 1940, after the armistice, France was divided into an occupied zone in the north and a free zone in the south. Many French people, frightened by the presence of the Germans in the streets, took part in the exodus. Jewish families felt particularly threatened, especially as the Vichy regime willingly accepted the anti-Semitic ideology promoted by the Nazis.

Suzanne in 1941, at Lozère, in the Seine and Oise department

Dina and Paul, standing, with Alta and Suzanne in the center, in 1941

The fate of the Jewish population was sealed on January 20, 1942 at the Wannsee Conference, at which the “Final Solution”, i.e., the extermination of the Jewish population, was set in motion. The family was hit hard very early on, sadly, by the arrest and deportation of Suzanne’s brother, Paul, who was deported to Auschwitz on March 27, 1942 on Convoy No. 1. Symcha and Alta then decided to leave Paris for the free zone, taking Suzanne with them. They hoped to keep their family safe.

The family sought refuge in St-Hilaire-de-la-Côte, in the Isère department

After several stops along the way, Symcha, Alta and Suzanne arrived in Lyon. By 1944, the danger was tangible. Roundups were increasing and Symcha was looking for a safe place, preferably in the countryside, to hide his family. He met a man called Alexandre Rey, a customs inspector in Lyon, who offered to hide them in his family home in Saint-Hilaire-de-la-Côte in the Isère department. Mindful of the ever-present risk, they left for the countryside, thinking it would be safer, in March 1944.

Saint-Hilaire-de-la-Côte was a small rural community with a population of about 600. The family lived in a hamlet called Hameau du Plantier, on a hillside in the village, in a large Dauphinoise-style house. They hid their true identity. Symcha called himself Joseph, his middle name, and obtained false papers in the name of Jacob Pick. In the village, however, he was known as “Father Joseph”. Alta became Adèle and then Anna. These pseudonyms were used to “Frenchify” their identities.

Mr. Rey’s house at St Hilaire de la Côte

The family became friendly with their neighbors. Alta fetched milk from the neighbouring farms, but Joseph, who knew they were under threat, remained worried. One day, the family went to a nearby farm belonging to a Mr. Jaquier (whom we were lucky enough to meet) to drop off and hide some trunks, which no doubt contained some personal belongings. Suzanne and her mother would eventually go back to retrieve them when they returned from the camps.

Joseph formed a bond with Antonin Jaquier, who was then 14 years old. He confided in him his anxieties and fears. He often went out into the surrounding countryside to look for places to hide in case the Germans arrived. Mr. Jacquier described him to us as a good, very kind man with whom it was easy to talk even though it was clear that he was afraid of what might happen to them.

After the war, Suzanne spoke about her involvement in the Resistance. She had helped the rebels to obtain ration coupons in association with other young people in the area. She mentioned the pseudonym of “Toto”, the person who was in charge of the network, a Mrs. Jeanne Adolf and a certain Sabine. However, these details could not be formally verified after the war and were therefore not accepted by the commission responsible for approving requests for recognition for members of the French interior resistance movement.

Joseph’s murder and Suzanne’s deportation

In the spring of 1944, several tragic events occurred in the ranks of the Resistance: in May, the villages of La Frette, Longechenal, Bévenais and Grand-Lemps were surrounded by the Militia and the Gestapo, in an effort to destroy the resistance unit that was based in an old farmhouse near Bévenais. Unable to find the resistance fighters, the Militia blew up four houses and arrested about 20 locals. Among them were some resistance members, who were arrested and beaten in a classroom at the school of La Frette, to make them confess where the group was hiding. As a result, several resistance fighters were interned in Montluc prison in Lyon and later deported to Germany.

On July 12, a fight took place at the Col du Banchet between Guy Roger’s group of resistance fighters and the enemy. The resistance fighters’ mission was to attack a German convoy that was heading back to Lyon. The ambush turned out badly, as the German convoys were escorted by militia cars to protect them. Three resistance fighters were killed: Henry Porchier de La Frette, Alfred Buttin de Rives and Tino Langafamme. The survivors retreated to Longechenal. Paulette Jacquier-Roux, known as Marie-Jeanne, was captured and taken to Bourgoin where she was interrogated, and then locked up for the night on the second floor, from which she managed to escape by jumping out of the window.

It was as a punishment for this that the Germans and the militiamen went to St-Hilaire-de-la-Côte on the morning of July 13. They began by going to the home of Louis Ballay, a farmer who was accused of providing food for the rebels. When he failed to provide satisfactory answers to questions about the resistance group’s whereabouts, he was taken to his farmyard and hanged from a tree. They then went to Mr. Rey’s house, no doubt already aware that a Jewish family was hiding there.

Anticipating shouting, Joseph Borucki, awakened with a start, approached the gate, where he was grabbed through the bars. After trying to get him over the gate, the militiamen agreed that he should go to fetch the key. The militiamen and Germans then went into the house and ordered Alta and Suzanne to get dressed and go with them.

Joseph was manhandled and slapped, then loaded with a box of ammunition.

To force him to move forward, a German soldier took off his flannel belt, tied it around Joseph’s neck and pulled him violently. Thus, surrounded by militiamen and German soldiers and followed by his wife and daughter, Joseph was led to a spot near the Col du Banchet, where the previous day the La-Frette Resistance group had ambushed the German convoy. There, a militiaman, who was recognized as being Guy Éclache, from Grenoble, summarily executed Joseph with a burst of machine gun fire. Joseph Guillerme, a farmer from La Murette, who was on his way to Mottier to fetch some pigs, was stopped by chance by the Germans and witnessed the whole scene. It was he who, after the war, identified Guy Éclache, a notorious member of the Grenoble police force and Nazi collaborator, as the person responsible for Joseph’s execution. Éclache is said to have told him: “Pik, kiss your wife and daughter for the last time” before shooting him dead in cold blood.

According to Mr. Jacquier, Joseph’s body was discovered near the church by a Mr. Maréchal, the local rural policeman, who was curious about the identity of the corpse. A declaration was made at the town hall reporting the discovery of a body in the Banchet area, according to the statements of Joseph Guénard, the town hall secretary. The body was then buried in the cemetery of St-Hilaire-de-la-Côte on July 14th.

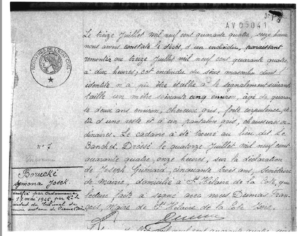

Judgment regarding the death of Joseph Borucki from the Court in Vienne.

It was not until 1946 that Joseph’s identity was confirmed by a judgement handed down by the Court of First Instance in Vienne.

When they were liberated from the camps, Suzanne and Alta returned to St-Hilaire-de-la-Côte to collect Joseph’s body, which was later buried in the Bagneux cemetery in Paris.

Joseph is listed among the victims of the Shoah by the Yad Vashem Memorial in Jerusalem, Israel. His name also appears on the commemorative plaque at the Chambarand camp in Viriville, Isère, and on the memorial erected near the site of the fighting at the Col du Banchet in La Frette.

The Memorial in Frette, Isère

The Resistance Memorial in Viriville, Isère

Suzanne’s itinerary and her deportation to Auschwitz

Guy Éclache, after having shot Joseph, put Suzanne and Alta in a truck that took them to Bourgoin. They were then taken to the Montluc prison in Lyon, then transferred to the Drancy internment camp, near Paris, and finally deported to Auschwitz: Suzanne on Convoy n°77 on July 31, 1944 and Alta on Convoy n°78 on August 11, 1944.

Suzanne arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on July 24, 1944 and was tattooed with the number A 16 676. Alta and Suzanne were separated, given that Alta was deported to the Ravensbrück camp. This camp, created in 1938 by Himmler, was only for women and children. The fact that Alta was not French, but Polish, could account for this. At Ravensbrück, Alta befriended a young woman of Suzanne’s age, Lucette, whom she protected during her 9 months of deportation. She wanted Lucette to meet Suzanne, if ever they came back from the camps.

According to her application for recognition as a deportee, Suzanne was in Birkenau from 4 August 1944 to January 1945, when she was transferred to Ravensbrück. She remained in this camp until March 1945. At that time, the Germans were caught in a pincer movement by the Allied advance and evacuated prisoners and removed records as they went along to try to hide their crimes.

In March 1945, Suzanne was sent to Malkow camp, which was annexed to Ravensbrück, until April 1945. She returned to France on May 17, 1945.

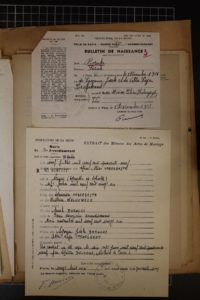

Application for the status of Deportee, page 4, 1956

As to the circumstances of her liberation, Suzanne would tell her family that she and the deportees were surrounded by guards, and then left stranded in the wilderness. With the help of the local population, they were rescued and later repatriated.

She rarely spoke to her children about her deportation. Like many survivors, she kept silent about the unspeakable to spare her family. She recounted a few details, such as the hunger and the mutual cooperation among the deportees to share the little food they had. She is said to have crossed paths with the Nazi doctor Joseph Mengele.

Alta’s liberation was quite different, since she had remained in the Ravensbrück camp, from which she was freed by the Swedish Red Cross. The Nazi guards negotiated their impunity in exchange for the release of female prisoners. Along with some of the other women, Alta was taken to Sweden before finally returning to Paris.

Alta and Suzanne both went via the Hotel Lutétia, in Paris, which served as a reception centre for the deportees.

A medical report, drawn up on her return from the camps, shows that Suzanne lost nearly 50 pounds, that she suffered from stomatitis and that she had scarlet fever.

Fiche médicale Suzanne Borucki

Suzanne subsequently suffered from tuberculosis. She was treated in a sanatorium for 6 months. She says that she underwent extensive and painful medical treatment, but it was there that she regained her zest for life.

Suzanne’s journey, drawn by Lou, Maelys and Mathéo

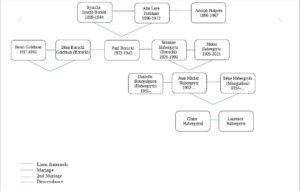

Suzanne’s family tree, drawn by Sarah and Cassandra

Suzanne’s life after returning from the camps

Suzanne in June 1945

Suzanne was reunited with her mother, Alta, and helped her in the shop at 19 rue du Caire in Paris, which had been returned to them by the French state. Alta later got remarried, to a man called Adolphe.

Two encounters were to shape Suzanne’s life. By chance, she met up with Lucette, the young woman who had been deported to Ravensbrück with Alta. The two young women would remain friends all their lives.

Suzanne also met her husband, Eddy Moïse Habergrytz, through her mother. Eddy parents had been deported and killed, and at the end of the war he was taken in by his aunt Tolé. Tolé had remarried a man called Joseph, who happened to be Adolphe’s brother.

Alta and her brother-in-law organized a meeting between the two young people, who were married on July 9, 1949 at the town hall in the 3rd district of Paris.

Marriage certificate, from the Seine prefecture.

Suzanne and Eddy’s wedding photo, 1949

The young couple went to live at 11, rue Taylor, in the 10th district of Paris.

Suzanne and Eddy had two children, Danielle was born in 1951 and Jean Michel in 1952.

They worked together in a store on the rue Saint Denis in Paris until they separated in 1969. Suzanne then gained her independence by working at Galleries Lafayette.

She devoted her time to her children and granddaughters, Laurence, born in 1987, and Claire, born in 1990.

Alta died in 1972 and Suzanne in 1991.

We feel honored to be able to share Suzanne’s life story with her family and to celebrate the memory of an exemplary life of love and courage in the year of the 30th anniversary of her death.

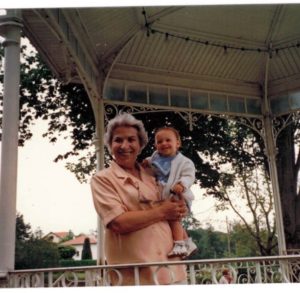

Suzanne and one of her granddaughters in 1988

Suzanne and her daughter in 1988

Suzanne and her granddaughter Claire, in 1991, shortly before she died

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Je suis totalement bluffé par cet extraordinaire travail de documentation. Bravo à tous, profs et élèves. Grâce à vous le devoir de mémoire prend toute sa valeur et le souvenir de tous ces invisibles qui ont construit notre Liberté et la qualité de vie qui en découle se grave à jamais dans le marbre.

Je suis à la fois, ému, bouleversé, admiratif, et bien sûr reconnaissant pour ce travail exceptionnel que vous avez accompli.

J’ai appris beaucoup de choses que j’ignorais sur ma famille, ma tante Suzanne et ma grand-mère étaient restées très discrètes sur ces années noires, sans doute pour nous préserver.

Je vous adresse dans le désordre de mon émotion, mes sincères félicitations, ma reconnaissance et mon admiration pour ce merveilleux cadeau que je garde précieusement et que j’ai déjà transmis à mes filles qui sauront grâce à vous, transmettre à leur tour, l’histoire de notre famille a leurs enfants.

Je n’oublie bien sûr pas Mme Katia Verhoeven, votre guide, sans qui ce travail mémoriel n’aurait sans doute pas vu le jour.

Avec mon infinie reconnaissance.

Patrick Goldman