Suzanne Boukobza, née Barman

This biography was written by Iman K., Oviya S. and Sara H., 10th grade students at the Lucie Aubrac High School in Courbevoie, Paris, following a very emotional meeting with Suzanne and Albert Boukobza on March 30, 2019.

Their conversation, which lasted several hours, was recorded. The students would like to reiterate to Suzanne their admiration and affection for her and to thank her, once again, for having graciously received them at her home to share this painful memory with them. They were there to collect information to enrich this biography but they also met two exceptional people: Albert and Suzanne.

Suzanne Barman was born on August 18, 1928 in the 10th district of Paris. Her parents came from Eastern Europe, which they fled to join family living in Paris: Wolf Barman, her father, was born in Russia on October 10, 1898 and her mother, Toni Bar, in Siret in the north-east of Romania on January 12, 1904. She was the last of a dozen siblings. On their arrival in France, Wolf stayed with his sister in Saint-Ouen and Toni with her aunt in Montmorency. Introduced to each other by their families, they married in Paris in 1924. However, neither of them acquired French nationality, despite their repeated requests for naturalisation.

Suzanne was the youngest of three siblings: Jules, the eldest, was born on March 25, 1925 and Armand, the youngest, on May 18, 1927. Having arrived in the country penniless, Wolf worked on markets and flea markets, where he sold rags. In 1933, at the age of 35, he died of tuberculosis. Toni, who did not work outside the home, was then unable to support her three children. She therefore entrusted the two youngest to the Rothschild orphanage at 15, rue de Lamblardie, in the 12th district of Paris. She kept the eldest child, Jules, with her to help her with small sewing jobs.

Toni Barman with her three children at the orphanage at 15, rue de Lamblardie (photo courtesy of Suzanne Barman)

At the orphanage, the young Suzanne found herself separated from her brother because the four grades were not combined. Girls and boys were educated differently, while boys ate from bowls and girls from plates. She was allowed a weekly visit from her mother, as stipulated in the regulations. A rather naughty child and therefore often punished, she was sometimes deprived of these visits. Most of her classmates were orphans and some had the same migratory family background. At the orphanage, she celebrated her bat mitzvah in a group. Cut off from the outside world, she was not yet aware of the rise of anti-Semitism.

War was declared in September 1939, followed by the “phony war” and then the crushing victories of the Germans, who arrived in Paris in June 1940[1]. As the occupation progressed, the children in the orphanage were dispersed. Armand left the orphanage in 1940 to start an apprenticeship in jewellery, on the rue des Rosiers in the 4th district. Suzanne continued her schooling at the school on rue Vauquelin, in the 5th district. This school was run by the UGIF, the Union Generale des Israelites de France, a grouping of all Jewish assistance initiatives imposed by the Vichy Government and the German occupying forces [2]. She liked to go walking in the Bois de Boulogne with her friends, doing gymnastics (she was very talented at acrobatics). Soon afterwards, from 1941, she had to wear the yellow star, which she hid under her jacket.

Suzanne was a young acrobat (photo courtesy of Suzanne Barman)

On May 17, 1944, her brother Jules, then 19 years old, was arrested in the street by the French police. He was not wearing the star and tried to escape, but was caught by two police officers who chased him. He was deported to Auschwitz and then transferred to Bergen-Belsen, from which he was never to return. More than forty years later, Suzanne discovered by chance, while reading Dora Bruder by Patrick Modiano, a record of the circumstances of Jules’ arrest[3]. However, neither Armand nor his mother were deported.

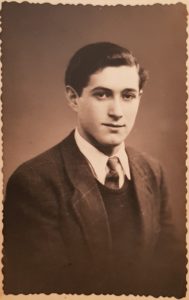

Photos of Jules Barman (courtesy of Suzanne Barman)

On the night of July 21-22, 1944, the French police arrested all the girls from rue Vauquelin and transferred them to the transit camp in Drancy[4]. That same night, 400 other children were arrested. While on the bus, to boost their courage, they sang La Marseillaise. Once in Drancy, where they remained for about ten days, they slept outside and played with a ball while waiting hopefully for the arrival of the Americans and the Liberation of Paris, which unfortunately came too late. In Drancy, the Jews were aware that they were to be taken to the East, to a disturbing and dangerous destination they called “Pitchipoi”. The young girls from rue Vauquelin stuck together to reassure themselves as best they could. Suzanne was sure she could count on her friends: Jeanine, Ida, Yvette, Suzanne, Denise, Anna, Herta and Mathilde.

Unfortunately, more Jews, including children, were being transferred to Drancy all the time. The camp commander, Alois Brunner, a ruthless SS officer, ordered round-ups to be carried out in order to “fill” his last large convoy from Drancy. Of the 1309 people who were deported on convoy 77, 324 were children or infants. On July 31, 1944, Suzanne left Drancy for Bobigny and then Auschwitz, where the convoy arrived on the evening of August 2. The journey was appalling, with the detainees crammed into cattle cars. Suzanne remembers the lack of air, the thirst, the difficulties encountered by the elderly, the air of madness, the straw on the ground, the smell and the promiscuity. A simple bucket and a sheet served as a lavatory for the entire wagon. The train stopped occasionally to empty the buckets and some people tried to take advantage of the opportunity to escape.

On arrival in Auschwitz, there was a long wait in the cattle car, over three hours with no way out, waiting for the previous wagons to be emptied[5]. The doors opened. It was night time. Children were screaming, and mothers too, while the Kapos were shouting and their fearsome dogs were barking. Suzanne was petrified and as she jumped out of the wagon her feet slipped from under her. Fortunately, her friend Jeanine, along with some others, pulled her up and gave her friend the courage to continue. Almost immediately, a doctor, the infamous Mengele, made a “selection” with his stick: to the right, those who could work; to the left, everyone else. Suzanne was sent to the right. Mengele tapped her on the shoulder and said, chillingly, “Next time”. Suzanne then went through all the stages of dehumanization: getting undressed as a group in the Sauna [disinfection area], having her head shaved under duress and getting a tattoo (which she had removed when she returned to France). She was given so-called disinfected clothes and odd shoes that were the wrong size but which she had to keep all winter. This moment is obviously etched in her memory: “One cannot forget that. I think about it every day of my life.”

From the beginning, blows rained down and the deportees had to move fast. Yet Suzanne stayed with her friends who, for her birthday, August 18, 1944, managed to gather together some bread and a little jam. They were placed in quarantine in a little barracks in Birkenau, part of the Auschwitz concentration camp complex. They were subjected to long, cruel and deadly roll calls: standing for hours, they were counted and recounted. There was a constant dread of diseases, such as typhus, and a fear of being taken to the infirmary because the deportees knew that they would not come out of it alive. Every day, more people died.

Several times, Suzanne and her friends had to return to Auschwitz for the selection rounds. She remembers one time in particular: “This selection was deadly, really horrible. We had to stand up from morning to night without eating, without drinking, without sleeping. Standing there just waiting, waiting, waiting, waiting. And you had to stay in line. They passed among us and hit people with whips. If you shifted weight from one foot to the other, they didn’t like it. You had to stand to attention. How can you stand to attention from morning till night? It was very hard. When they came by, we tried to protect and support each other.”

Suzanne felt that she and her quarantined comrades were doomed to die: “We were meant to be gone,” she says. But the massive arrival of more than 400,000 Hungarian Jews and the closure of the neighbouring Gypsy camp in August 1944 delayed the assassination of the deportees from Birkenau. Similarly, on October 7, 1944, the Sonderkommandos, cruelly assigned to work in crematorium, rebelled, knowing that they too would die. They destroyed camp crematoriums III and IV[6]. At the same time, the Germans were looking for labour in Czechoslovakia’s arms factories. Suzanne and her comrades were sent there. This was “lucky” according to Suzanne: “This was a liberation in itself. Auschwitz meant certain death. If the crematoriums had not been demolished, we would have ended up there. Fortunately, they asked for workers at Kratzau; otherwise we wouldn’t be here.

Indeed, on October 28, 1944, Suzanne and her companions left Birkenau in cattle cars without knowing where they were being taken. The journey was atrocious. They arrived in Kratzau, Czechoslovakia, to work in an weapons factory. In addition, weapons (shells, grenades, etc.) had to be painted with paint so toxic that the SS gave the girls a glass of milk before work. The camp was a long way from the factory, almost 4 kilometres away, a journey that had to be made on foot each day. On the long hike to the factory, they were forbidden to stop, even to pick a dandelion on a bridge, as Suzanne still remembers over 70 years later. At the camp, conditions were harsh: two girls slept together on single bunks. Suzanne slept with Marie, with whom she maintained a strong and supportive relationship. The SS commander of the camp was particularly cruel: she gave beatings and slaps, as Régine Jacubert recalls in her memoirs[7]. Each of the girls tried to nourish herself as best she could: Mica, Ida and Régine stole potatoes; Suzanne and another friend stole sugar. Yet in the midst of this dismal scene, one of the deportees gave birth and her baby survived. Miraculously, he was not murdered.

The Red Army liberated Suzanne and her comrades on May 9, 1945, the day after the unconditional surrender of the German army. The Soviet soldiers terrified French women who wanted to leave Czechoslovakia quickly. Still sticking with her friends, including Jeanine, Suzanne took a freight train and crossed Europe to return to Paris. On arrival in the capital, Suzanne was sent to the Lutetia (a hotel designated to receive Jews on their return from the camps), where she was noticed by the health services because she was extremely thin, weighing just 55 pounds, and had such weak lungs. She was then sent to the Les Houches sanitorium in the Savoie region. She stayed there for a few months and was then taken care of in Moissac in a center run by Bouli and Shatta Simon, said to have been “amazing people”[8]. In May 1949, Suzanne took part in a teacher training course in Geneva and met her future husband, Albert Boukobza, from whom she would never part.

Suzanne was to remain very reserved about this dramatic period of her life and would not speak about it until 2019, when she embarked on the difficult task of remembering it all for the Convoi 77 association. She explains her silence like this: “I never wanted to talk about it, even to my children. They went with me to Auschwitz. They saw what they saw and it was my duty to do it. I went there with friends, even with schools, but I didn’t speak, I couldn’t speak. I had the impression that if I were to talk, I would have stayed there, never to escape again. Twice, I went to Auschwitz. I was asked to speak but I replied: “I don’t know, I can’t do it”. Talking about it is very difficult. Words cannot describe the cruelty. Words are nothing compared to the pain. There are no words to express this great suffering. I get the shivers, and goose bumps. It’s very hard to talk about it.”

Nevertheless, despite not having shared her testimony, she has maintained very strong links with the other deportees from this convoy, who she sees regularly. She feels that her great luck and her strength was due to not having to be separated from her friends, and that this enabled her to survive the deportation.

At the time of writing, Suzanne is 91 years old. She has 3 children and 8 grandchildren, which she considers as being her greatest achievement and of whom she is very proud. She is a bubbly, exceptionally energetic and gentle lady. The reason she chose to testify was to convey a message of tolerance to young people.

Almost a year after the publication of this biography, Sophie Davieau-Pousset, the teacher who originally submitted it, sent us this very moving addition, which is illustrated by three images below the text:

“During our discussions with Suzanne, she confided to us that her brother Jules had been arrested by the French police in May 1944, two months before she herself was arrested. Jules, then 19 years old, was transferred to Drancy and then deported to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, from where he never returned.

For several decades, Suzanne was unaware of the circumstances of her brother’s arrest. In addition to her grief, therefore, there had also been the pain of not knowing the facts about what had happened to him, however brutal and painful they may have been.

Much later, in the 1990s, Patrick Modiano began researching Dora Bruder, a Jewish teenager whose parents reported her disappearance in the newspaper Paris Soir in 1941. He felt quite literally haunted by this missing person report. Thus, starting from this small ad, Patrick Modiano set out to retrace the life of Dora, a runaway teenager caught up in the turmoil of the dark years of war. His investigations led him to search the archives, in which he discovered that Dora had been arrested and that she too had been transferred to Drancy and then deported to Auschwitz, where she was killed. Born in 1926, Dora was thus about two years older than Suzanne, and was deported at the same age as Suzanne. The two young girls, both of immigrant Jewish parents, followed the same itinerary: Paris, Drancy, Auschwitz. It was not, however, this shared experience that struck Suzanne the most when she read Patrick Modiano’s book, which was published in 1997. During his research, Modiano came up with a number of possible theories to fill in the gaps in the traces left by Dora. He looked at the experiences of several young Jewish people in order to determine what may have led to the arrest of the teenager in 1942. He made copies of various archived records which, when compared, provided some leads. Among them was this one:

“May 17, 1944. Yesterday at 10:45 p.m., during a roundup, two security policemen from the 18th district arrested the French Jew, Jules Barman, born on March 25, 1925 in the 10th district of Paris, residing at 40, bis rue du Ruisseau (18th district), who, on being questioned by the two guards, had fled, since he was not wearing the yellow star. The guards fired three shots in his direction without hitting him and arrested him on the 8th floor of the building 12 rue Charles-Nodier (18th district) where he had taken refuge.”

This “French Jew, Jules Barman” was Suzanne’s brother. The date of birth and the address left no room for doubt. For Suzanne, this unexpected, brutal discovery came as a shock. She tried in vain to find out from Modiano the source of this archived record.

During our meetings, Suzanne told us about this striking discovery. We then set out in search of this document, which was so cold and so tragic. Modiano mentioned the Yivo Institute and the Prefecture of Police in Paris. We contacted both organizations, and while the first did not have the record in question, the second did. Despite being in the midst of a reorganization and the coronavirus crisis, the personnel were kind enough to find us not only this document, but two others, which attest to Jules’ presence at the Police Headquarters in Paris and to his transfer, the day after he was arrested, to the Drancy camp.

It was with great sadness, in June 2020, that we handed Suzanne these short, blunt records of her brother’s arrest by the French police, and his subsequent deportation and assassination by the Nazis.

References

[1] Antony Beevor, La Seconde guerre mondiale, Le livre de poche, 2014.

[2] Michel Laffitte, Un engrenage fatal. L’UGIF face aux réalités de la Shoah, 1941-1944, Paris, Éditions Liana Levi, 2003

[3] Patrick Modiano, Dora Bruder, Gallimard, 2002, p. 108.

[4] Annette Wieviorka et Michel Laffitte, À l’intérieur du camp de Drancy, Paris, Perrin, 2012, 382 p.

[5] Annette Wieviorka, Auschwitz, 60 ans après, Paris, Robert Laffont, 2005

[6] Shlomo Venezia, Sonderkommando, Dans lʼenfer des chambres à gaz, Albin Michel, 2007

[7] Régine Skorka-Jacubert, Fringale de vie contre usine à mort, Le Manuscrit, 2009, 251 p.

[8] Catherine Lewertowski, Les enfants de Moissac, 1939-1945, Flammarion, 2003

Images

Contributor(s)

Iman K., Oviya S. et Sara H., 10th grade students at the Lucie Aubrac High School in Courbevoie, Paris, under the supervision of Sophie Davieau-Pousset, their history teacher.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Chère Suzanne,

un grand merci d’avoir participé à notre projet et d’avoir reçu ces élèves et leurs enseignantes pour qu’elles puissent instruire votre biographie. La bande d’amies, formée à Kratzau, et si souvent réunie, les 9 mai, pour commémorer votre libération, restera gravée dans mon cœur.

Serge

BRAVO aux élèves pour cette superbe biographie, vivante, émouvante et informative. Et merci à Suzanne Barman Boukobza de leur avoir permis de vous rencontrer.

Bonjour et merci pour cette biographie. Je m’appelle Sarah Barembaum et je suis une petite-cousine de Violette Parsimento, également arrêtée au foyer de la rue Vauquelin et déportée à bord du convoi 77 pour Auschwitz. Il semble que Suzanne et Violette se soient connues. Je cherche à parler à des gens qui ont connu Violette et qui pourraient m’en dire plus sur elle. Serait-il possible de contacter la famille Boukobza? Merci par avance de l’attention que vous portez à ma requête.