Simone GUEMPIK, 1927 – 1944

Hello,

We, the 2nd class of 9th grade students at the Blés d’Or junior high school in Bailly-Romainvilliers, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France, became involved, together with our French and History teachers, in the Convoy 77 project. We chose to participate as part of our duty of remembrance and to pay tribute to three of the people who were deported on this convoy.

We chose to mix fictional autobiography and narrative to bring to life these three missing persons that we chose in class. First of all, the boys’ attention was drawn to Salomon Israël on the basis of his age, which was 17 when he was deported, because we felt an affinity with him. We discovered that he had been deported together with his mother, Sarah Israël, so we studied both mother and son. The girls chose to work on the biography of Simone Guempik for the same reason.

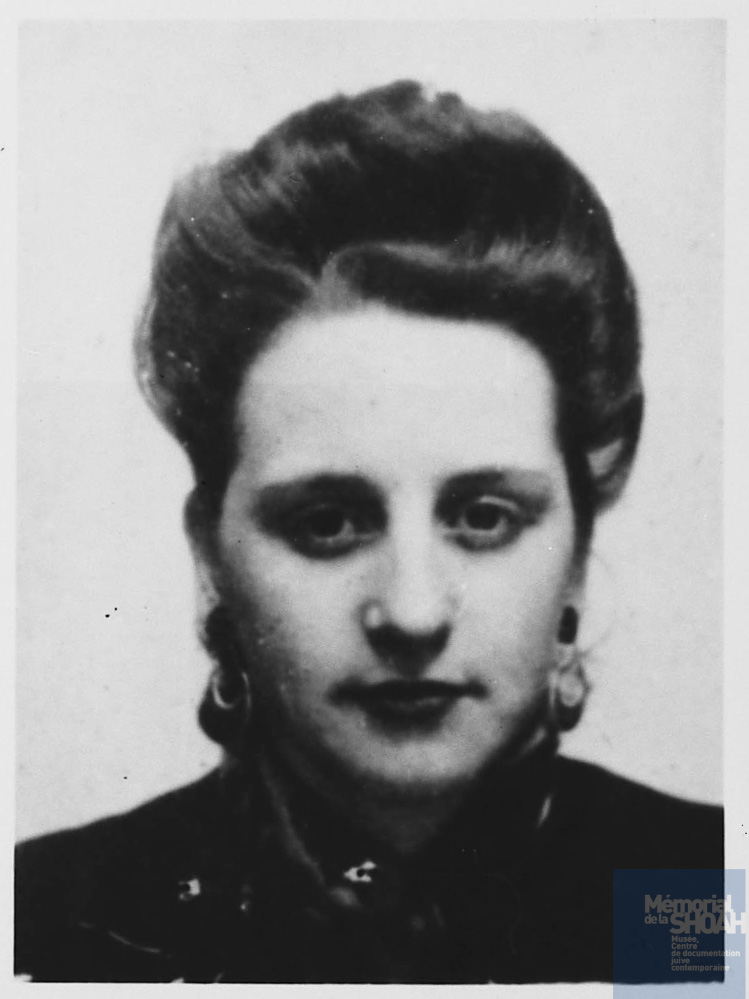

We used documents provided by the Convoy 77 association as sources for the biography, along with records from the civil registry office in Paris. We also gathered information from the archives of the Shoah Memorial website and the Yad Vashem website. Reading the Diary of Hélène Berr helped us a lot, as did the autobiographies of Ginette Kolinka, Henri Borlant, Simone Veil and Ida Grinspan. We also watched an interview with Marceline Loridan, “Ma vie balagan” (My chaotic life). During our research, we were lucky enough to encounter one of Simone’s nieces, Arielle Guempik, with whom we had a videoconference and who kindly provided us with some photos that she still had in her possession.

These various sources enabled us to learn more about the people we studied so that we could “bring them back to life” and not let them be forgotten. We found two spellings for Simonne, one with only one n, French style, and one with two ns, Russian style. We chose to use only one spelling, the French version, in the biography.

Dear readers,

My name is Simone and this is my biography, my story, my life. I promise that it is the truth and nothing but the truth and that I have not made anything up. I have stayed true to myself so that you can see the person I was. You don’t have to read it, but if you choose to stay, it will be a way for me to show myself as I was and about my life as a French Jew.

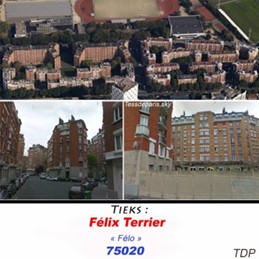

First of all, as I told you at the beginning, my name was Simone, Simone Guempik. I was born on February 22, 1927 at 123 Boulevard de Port-Royal in the 20th district of Paris. I was a young girl like any other, I went to school and I wanted to continue my studies. I lived at 6, rue Félix Terrier in the 20th district of Paris. It was a relatively poor neighborhood, but I had no complaints about it.

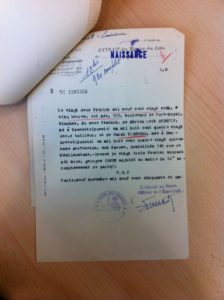

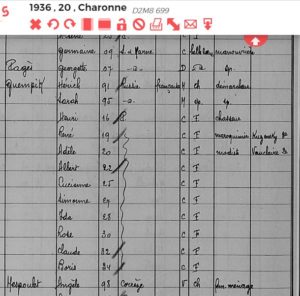

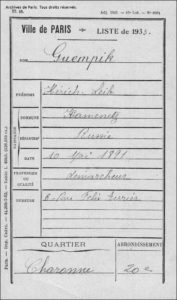

This is Simone’s birth certificate and from it we learned the names of her parents, Hereik Leib Guempik and Sarah Klemberg. She was born on February 22, 1927 at 5 am, on boulevard de Port Royal in Paris. Her father was born in 1891 in Kamenetz, Ukraine, a city that was ceded to the Russians in 1921. He worked as a tailor. Her mother was born in Smokretch in Russia in 1895 and was a housewife. They lived at 14, rue de Ménilmontant in the 20th district of Paris.

This compilation of photos depicts the Félix Terrier neighborhood in the 20th district of Paris. We found this address thanks to the 1936 census and a certificate of residence issued in 1951. We note that it was a recently built, working-class neighborhood and that the road was opened in 1929. This is line with other information we have about Simone’s life.

I was of Ukrainian origin since my parents were born there. My father’s name was Heirch Leib and he was born on May 10, 1891, while my mother’s name was Sarah and she was born on April 13, 1899. Before coming to France with my mother, my father had already visited France once before, in 1907. He came with his two brothers, Salomon and Yankel, and their mother, Bassia Bodner. There were many attacks on Jews in Ukraine and it was for this reason that they chose to leave the country. They stayed in various households in the Bastille area of Paris. In 1909, he went to Russia to find his wife, Sarah. My maternal grandparents were against the marriage, so my father took my mother away. They lost their marriage certificate on the journey to France, which is why they remarried in Paris. He then fought for the French in the 1914-18 war, notably at the Battle of Verdun. In 1924, my parents, along with their first four children, who were all born in Paris, requested and were granted French citizenship. This is proof that they had decided to settle permanently in France. He was well-integrated and loved France, which he saw as a land of freedom, and where he felt at home and totally safe.

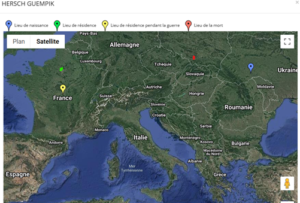

On the Yad Vashem website, there are maps available relating to each deported person, showing their places of birth, residency and death. This is the one pertaining to Hersch Guempik

The father’s naturalization certificate, issued in 1924, and his voting card, from 1933, prove that he and his family wanted to integrate into French society as much as they could.

In 1939, my parents had a large family to raise. We were 12 children in all, 5 boys and 7 girls. The boys were Henri, who was 23; René, 20; Albert, 17; Claude, 7 and Boris, 5. As for the girls, they were Fanny, 25; Adèle, 19; Lucienne, 14; me, 12; Ida, 11; Rose, 9 and Danielle, 1. My parents also lost a child, Marcelle, in 1924. She died when she was only a few months old and her death had a profound impact on us as a family.

The sibling I was most close to was Ida, my little sister. Some of the older ones had already gotten married and moved out. I shared a room with my sisters. My brothers also shared a room, while the younger ones still slept in our parents’ room. Our apartment had 4 rooms. We didn’t have much money, but I was an optimistic child and content with what we had. My father was a door-to-door salesman, Henri was a delivery boy, René was a leather goods worker, Fanny was a shorthand typist and Adèle was a milliner. In our working-class neighborhood, there were a lot of Jewish people. Everyone in the building knew each other, so we were supportive of each other, and also of the newly-arrived immigrants. Our extended family was reunited in Paris. Our uncles, aunts and cousins all lived in the same district, so we saw a lot of each other. The only one who chose to leave was my uncle Salomon, who moved to the United States in 1915.

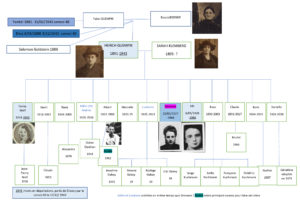

Here is a simple family tree showing that Simone’s paternal grandparents were Faitel and Bassia (the woman who came to France with Heirch). They had 4 children: Yankel, Dina, Salomon and Heirch. Only Salomon survived the Holocaust. Heirch, the son, and his wife Sarah had 13 children. And thanks to Arielle, we also know about some of the 3rd generation.

Some of the siblings in the courtyard of the apartment building: from right to left Simone, Albert and Hilda, standing, and Rose, Boris and Claude, sitting.

Here we have a photo of Fanny and Henri, with Heirch

And finally, here are the parents of the siblings, Heirch and Sarah, with René on the left, Henri in the center and Fanny on the right

The fact that they took photos suggested that they were well-integrated and wanted to be accepted as decent French citizens. They wore conventional outfits no visible signs of their religion or ethnicity.

At the beginning of the war in September 1939, our family felt secure because we had faith in the French army, we were all French citizens and my father was a war veteran. My father felt really well-integrated in France. Even though he was an immigrant, he saw France as his homeland. He was therefore deeply attached to it. René and Henri were drafted into the forces and we were a little worried about them. E In June 1940, when France was defeated, things began to change for us. We were afraid when the Germans arrived because my parents were conscious of their anti-Semitism. They were everywhere in Paris and I often ran into them on my way to school. Soon afterwards, we heard that René had been taken prisoner. E In October, when decrees were passed concerning the status of the Jews, anti-Jewish posters were put up and many of our neighbors lost their jobs. Paris was no longer the same; the mood had changed.

Intimidation and restrictions increased. We had to give back our radio and part with our only bicycle, we were forced to observe special shopping hours, and, more than ever, we were treated as undesirables. Albert decided to join the resistance. He couldn’t stand the way we were treated and wanted to fight. My parents decided to separate the children and hide them in the countryside in the free zone. The atmosphere at home became more and more tense and my mother was very sad.

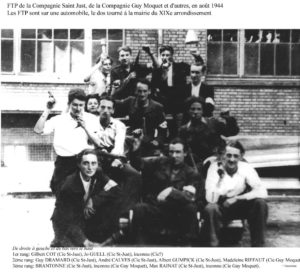

This photo dates from the liberation in August 1944. It depicts two FTP (Francs-Tireurs et Partisans) Resistance groups, the Saint-Just company, which was the one that Simone’s brother Albert joined, and the Guy Moquet company

My father was deeply troubled by the situation. Having put his trust in France, he felt betrayed. He felt humiliated by the stamp saying “Jew” on his identity card and he was frightened by the roundups that had begun in the spring of 1941. Some of our neighbors disappeared, but it appeared that only the men were targeted. As from 1942, we had to wear a yellow star sewn on our clothes, which was utterly humiliating. Our aunt Dina had chosen to leave Paris and move to Nantes, and in October 1942 we heard that she had been arrested. We never heard from her again. At the beginning of 1943, our uncle Yankel and his wife Rebecca were arrested and they too disappeared. The noose was tightening and we felt in ever greater danger. As a 15-year-old, I could see that they wanted to get rid of us Jews. And neighbors were still disappearing. There was talk of us being sent to work in the East. This journey into the unknown worried us. What had we actually done wrong? We had no more news from our family and the postal service was no longer working.

In December 1943, my father and my two sisters, Ida and Fanny, were arrested at our home and the police were looking for my brother Albert, who was in the Resistance. Meanwhile, Albert, convinced that it was the janitor who had turned them in, said he was going to blow up the janitor’s lodge. I was devastated. How were we going to survive without Papa and Ida, who was my alter ego?

My mother then decided to go and live in Montreuil with my sister Adèle to escape another potential arrest. I went back and forth between the two homes, trying to make myself useful.

My mother managed to stay in Paris and to keep her apartment despite the Aryanization of housing and the family’s involvement in the Resistance. Adèle was a perfume seller and had a boyfriend with whom she was very much in love. His name was Pierre Marlon, but he too was a member of the Resistance.

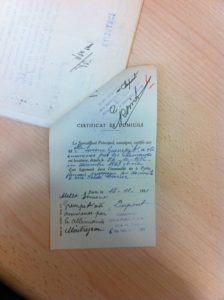

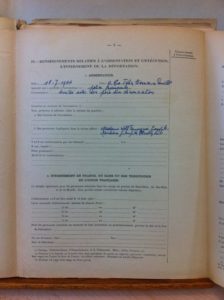

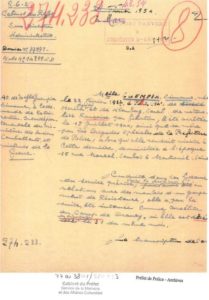

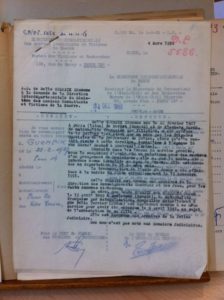

This document is Simone’s father’s arrest record. The heading reads: “Information relating to the arrest and execution, internment or deportation”

It was the French police who arrested Heirch, Fanny and Ida at their home following a tip off. We later learned that it was the janitor of the building who denounced them. In those days, as soon as people learned that others were Jews, they no longer felt any sense of solidarity. They turned everybody in without remorse. This was the reason that Simone’s father and two of her sisters were arrested. Two members of her family testified to having witnessed the arrest. They were subsequently deported on Convoy 63 on December 17, 1943. There were no survivors.

In June 1942, the violence against the Jews began to escalate. We know from Hélène Berr’s diary that Jews had to wear the Star of David sewn onto their clothes, that they could only go into stores at a specific time, between 3 and 4 p.m., and that they had to sit in second class on buses and on the subway.

On July 18, 1944, when I was on my way to visit my mother with my two sisters, Adèle and Lucienne, we were arrested in the street by the Special Brigade of the Paris police department. I was terrified, but relieved that my sisters were with me. We were initially taken to the depot and, on October 22, to the police headquarters where I was questioned for a long time. I was questioned at length about what I might know about Pierre Marlin and his resistance network. I left the police headquarters on July 26, absolutely distraught because I had just been separated from my sisters, and was put on a bus to Drancy.

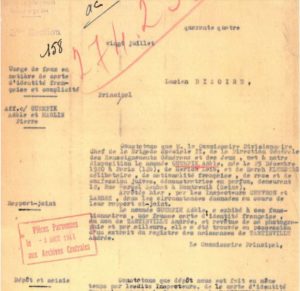

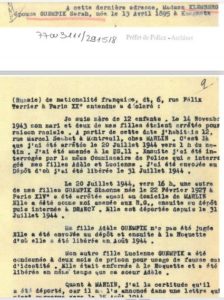

We know that Simone was arrested with two of her sisters, Adèle and Lucienne, but that is where the similarity ends. On July 20 and 25, Lucienne Gabay (her married name) was interrogated for using a false identity card. It was the same for Adèle. However, this raises a question: Where were they from July 18 to July 20? Their mother was also arrested for questioning, on July 20, at 1 a.m. We found her statement. Simone herself was only registered at the police headquarters on July 22 and she left for Drancy on July 26. She alone was sent to Drancy, while her sisters were incarcerated in the Roquette prison until August 1944.

Did her sisters escape deportation as a result of repeated interrogations? Did they thereby avoid being deported on the last convoy on July 31? They were interrogated mainly about the whereabouts of Adèle’s boyfriend, Pierre Marlin, who was an active member of the Resistance. (We know that he too was arrested shortly afterwards, for having produced fake identity cards and for keeping firearms at his home, and that he was then handed over to the authorities to be deported. He later wrote home with some news, but he never returned from the camps. Adèle continued to carry a picture of him for the rest of her life, even though she rebuilt her life and started a family). We also know that Sarah attempted to have her daughters released in the summer of 1944. As fate would have it, Sarah was freed on the same day that Simone left Drancy for Auschwitz.

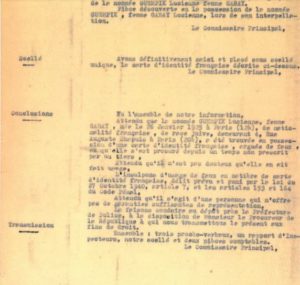

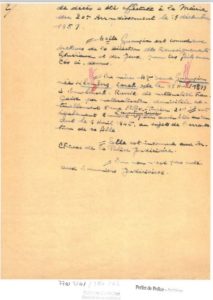

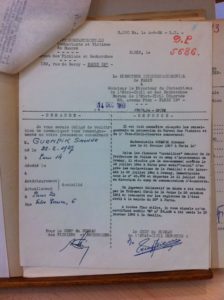

Sarah’s statement and, below, police documents relating to Simone’s arrest

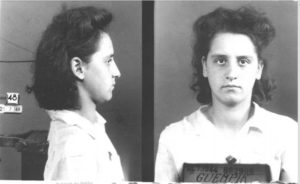

Photos taken of the three sisters by the police in July 1944 (Adèle at the top, Lucienne in the middle and Simone above

For France, Drancy camp symbolizes the mass deportation of Jews. It is a few miles north west of Paris, in the heart of the Cité de la Muette, which was designed in the 1920s as a model of urban social planning. It can be summed up in two figures: 67,000, the number of deported Jews (of a total of 75,000) who passed through the camp, and 80,000, the number of people identified as Jews (according to the racial criteria applied) who stayed there for between a few hours and the three years that the camp was in operation, between the summer of 1941 and the summer of 1944.

I was registered at Drancy with the number 26,970 on July 26, 1944.

I was totally lost. It was like a big labyrinth with big buildings forming a U shape. As we entered, we were all searched. I felt humiliated and disoriented.

It was French soldiers who worked in the camp. During the four days I spent in Drancy, I saw no German soldiers at all.

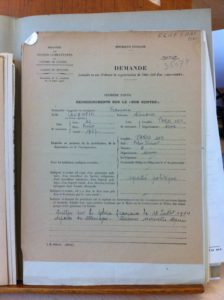

The certificate confirming that Simone was a victim of war includes her identity, her date of birth, her address and the words “political deportee”. It also says “Arrested by the French police on July 18, 1944 and deported to Germany” and then “no further news since”. It states that she was a political deportee but the reason for her deportation was her Jewish faith.

On Simone’s missing persons certificate, the circumstances of her arrest are described and at the bottom it is noted that she is recorded in the archives of the General Intelligence Directorate.

It also says that her mother, the widow Guempik, was interviewed on April 9, 1945, about her daughter’s arrest, that she was not found in police records and that it appeared that she was trying to trace her missing daughter.

On July 31, buses came to pick us up and take us to Bobigny railroad station. Once there, we were forcibly put into cattle cars regardless of age or gender. Even before we set off, it was horrible in the wagon because there were far too many of us, we had no private space and we were crammed together. No food or drinks were provided. After they got everyone in, the doors were closed, and it was quite dark inside. When the locomotive pulled away, some of the children started to scream, but they soon stopped. We spent many hours shut in the cattle car, so some people needed urinate, but there was only one bucket for everyone to use. A whole day went by, and many people complained about being too hot. As time went on, I heard fewer people talking, fewer children crying. The only thing you could do in that cursed wagon was pray. Some people said that our destination was called Pitchipoi.

This document comes from the Veterans and Victims of War bureau. It says that Simone Guempik was arrested in Paris on racial grounds on July 18, 1944, that she was interned on July 26, 1944 in Drancy under registration number 26970, and that she was deported on July 31, 1944 to the Auschwitz concentration camp.

On August 3, 1944, when I got out of the wagon, I saw a platform and a lot of people around me. Someone told us that if we were tired or had a child, we should go to the trucks. We did not know where we were, but there were big chimneys in the distance with lots of black smoke coming out of them and an acrid smell that caught our throats. At that moment, I saw a small child who was all alone, so I decided to take him in my arms to reassure him and that’s when someone sent me over to one of the trucks. They took us a short distance, towards a birch forest. We continued on to an underground room and there we were asked to undress ready for a shower. I found this very strange and also embarrassing, because I did not know the other people and men and women were all mixed together. I put on a brave face in front of the little boy so as not to worry him even more. And then some Germans closed the door behind us.

A number of records refer to Simone’s death, but they give conflicting information, which demonstrates the lack of knowledge and the prevailing ambiguity at the time. Some documents state that she died in Drancy, but then, according to a law passed in 1947, she was declared dead within five days of the departure of the convoy, i.e. on August 5, 1944. The archives of Birkenau-Auschwitz II are incomplete or missing.

As soon as Simone was arrested, her mother began the research and administrative procedures to try to trace her. She appears to have had some difficulty with the French language, since some documents were signed on her behalf. In 1946, Simone was pronounced dead on the basis that she was a “non-returnee” and in 1954, she was recognized as a victim of war and as a political deportee, having been deported on racial grounds.

Our research on Simone prompted us to look at what happened to the rest of the family: the children who were hidden in the countryside were found safe and sound, but several people died in addition to Simone, as can be seen in this extended family tree. We wanted the descendants of this family to be able to find each other on this tree. The spelling sometimes made it difficult for us to find them, when Guempik became Gempex for example. We were also unable to find the brother who was a prisoner of war on the lists of prisoners; might this also be due to a mistake in the spelling of his name?

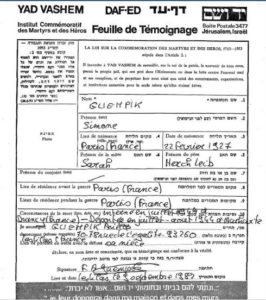

Arielle Guempik, the daughter of one of Simonne’s brothers, Albert, went to Jerusalem to fill in the Pages of Testimony at the Yad Vashem Memorial. These sheets are available in several languages, and allow visitors to testify to the existence of a person known to them who disappeared. This is like throwing a message in a bottle into the sea. It is sometimes the starting point in the search to find out what happened to a “non-returnee”. It was as a result of finding the Page of Testimony for Simone (see below) that we got in touch with Arielle, communicated with her by email, and then had a video conference.

Simone’s name remains forever engraved on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris and on the family tombstone.

Louise, Victoria, Margaux, Lauren, Louna , Aïdan et Jérémie.

Arbre généalogique:

| Maurice | |||||||||||||

| Yankel ( 1881-15/02/1943) Rebecca Lippelman | Léon | ||||||||||||

| Fanny | |||||||||||||

| Maurice | |||||||||||||

| Dina (1886- 9/12/1942) Avrum Herch Garber (9/07/1908) | Wolf (Paul | ||||||||||||

| Charles | |||||||||||||

| Isaak (Jacques) | |||||||||||||

| Léon | |||||||||||||

| Marcelle | |||||||||||||

| Faitel Guempik Bassia Bodner | Salomon (1888- ?) Goldstein

Paule Schouster (13/7/1915 à Paris) |

Ardine |

|

||||||||||

| ? | |||||||||||||

| ? | |||||||||||||

| Fanny (1914-1943) Joseph Wolf | Jean-Pierre Maguy |

|

|||||||||||

| Henri (1916- 1992) Louise Milstejn | Claude (1951- ) | ||||||||||||

| Herch-Leib (1891 – 1944) Sarah Klemberg | René ‘ (1918-2000) Fanny Jakubowiez //

Stéphanie 1979 |

Alexandra (1979- ) |

|||||||||||

| Adèle (dite Andrée) (1920- 2016) Jean-Marie Chrétien | Didier adopté (1944)

Paulette

// ? |

|

|||||||||||

| Albert (1923 – 1988) Madeleine Welk | Arielle (1962- ) | ||||||||||||

| Marcelle ( 1923-1925) | |||||||||||||

| Lucienne (1925-2013)

Marcel Gabay 1943 |

|

||||||||||||

| Simonne (1928-1944) | |||||||||||||

| Ida (1929-1943) | |||||||||||||

| Rose (1930-2003)

Lucien Kuchmann |

|

||||||||||||

| Claude (1932-2017) Francelyne Lajarrige | Murielle (1964- ) Laurent | ||||||||||||

| Boris (1934-2021) Claudine Heuze 1960 | Nadine (1967- ) Charles Cavanaugh |

|

|||||||||||

| Danielle (1938-2020) Georges 1964 | Géraldine (1973- ) | Mayana | |||||||||||

Français

Français Polski

Polski