Simone GOLDBERG

Hello, we are the 21 students in 9th grade class 3 at the Jean de la Fontaine junior high school in Le Mée-sur-Seine, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. Our class chose to study the life of Simone Goldberg, a 14-year-old French Jewish child who was deported on July 31, 1944 and died on August 5, 1944. We decided to reconstruct her life’s journey until her final days as a tribute to her.

This project has taught us many things, especially about the Second World War, including the life of civilians under the German occupation in France and also about the collaboration of the Vichy regime with Nazi Germany, in particular the arrest and deportation of Jews from France.

Simone’s life is an interesting one to study because her journey symbolizes the tragedy of the last days of the war. She was deported on July 31, 1944, on Convoy No. 77, the last convoy to leave Bobigny railroad station, even though the Allies had landed on the Normandy coast more than a month earlier.

We are going to include a dialogue that one of us wrote: she imagined talking with Simone to try to help make her come alive in our imaginations. We also wrote a biography of Simone, which we published on Wikipedia.

Simone Goldberg has her very own Wikipedia entry. We did this so that she would never be forgotten, not who she was, nor what happened to her.

I. Simone’s biography.

Simone Goldberg

Simone Goldberg, who was born in the 12th district of Paris on May 4, 1930 and died on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz, was a victim of the Holocaust.

Contents

1. Simone’s family background

2. The move to Nancy, Chaïm’s death, Claire’s birth, Herzsek’s naturalization.

3. The return to Paris, Michèle’s birth. Simone and Claire’s schooling. The anti-Jewish laws.

4. Herszek, Maria, Claire and Michèle’s arrest and deportation.

5. Louveciennes.

6. The arrest of the children and supervisors at Louveciennes, Drancy camp, and Convoy 77.

1. Simone’s family background

A photo thought to be of Maria and Herszek on their wedding day.

Grumberg family’s personal archives.

Herszek Goldberg and Maria Grumberg declared their intention to marry and, according to the law, they were then married on July 2, 1929. Their address at the time was 14, rue Sainte Croix de la Bretonnière in Paris. The witnesses at Herszek and Maria’s wedding were Bernard Goldberg (Herszek’s brother) and Marie Grumberg (Maria’s sister). Émile Auguste Dupocq (the Deputy Mayor) conducted the ceremony. Maria’s father was illiterate, which meant that he could not sign his daughter’s marriage certificate. Simone’s father was Polish: he was born in Szydlowice on February 3, 1896. Her mother was born in the in the 12th district of Paris on May 7, 1909.

Just under a year later, on May 4, 1930, Maria gave birth to Simone at 15, rue Santerre in Paris. Simone’s father was working as a tailor at the time, while her mother was an office worker. Her grandmother on her father’s side was called Hendla and her grandfather was called Chaïm. He was born in Poland, more specifically in Szydlowice, and Hendla was born in Radom, Poland. They fled the country to escape the pogroms. Chaïm Goldberg worked as a tailor. They had eight children, four girls and four boys. The maternal grandmother’s name was Rosa and the maternal grandfather’s name was Yako. They also had eight children. Rosa and Yako were married in Smyrna, Turkey on November 6, 1903, after fleeing Odessa, their home town, also due to the pogroms.

2. The move to Nancy, Chaïm’s death, Claire’s birth, Herzsek’s French citizenship by naturalization.

Might the Goldberg family have moved to Nancy because the grandfather was sick? Was it because their apartment in Paris was too small? Did Simone’s father go to Nancy for work and take over an apartment that was not his own, but the grandfather’s? We are not sure why the Goldberg family moved from Paris to Nancy. Simone was two years old at the time.

Naturalization is a means of applying for French citizenship. Herszek and his family were living at 14, Rue du Pont Mouja in Nancy when he became a naturalized French citizen on July 26, 1933. Herszek then became Henri, which was the French version of his name. In Nancy, Henri Goldberg still worked as a tailor while his wife, Maria, was a street vendor. Herszek had brown hair, blue eyes, a medium-sized forehead, an oval face and was 5’6” tall. He was exempt from military service on account of his age. Claire, who was Herszek and Maria’s second daughter and Simone’s little sister, was born on July 25, 1933 in Nancy, just one day before Herszek became French.

3. The return to Paris, Michèle’s birth. Simone and Claire’s schooling. The anti-Jewish laws.

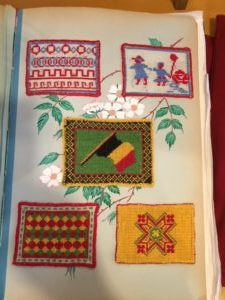

Needlework, possibly done by Claire and Simone at their school in rue Montmorency.

Simone went to a school for girls, which was at 8, rue de Montmorency in the 3rd district of Paris. She was there from 1937 to 1941. Her sister Claire also went to this school. Simone did manual work, namely sewing, just like her father.

France went to war in 1939 and was invaded in the summer of 1940. During this period, Simone witnessed or experienced the “exodus”, during which thousands of French people fled the fighting. On June 22, 1940, the French government surrendered, the fighting stopped and the Germans occupied Paris. Marshall Philippe Pétain was in power at the time. Simone saw her city change. Nazi symbols were everywhere and she often encountered German soldiers. In 1940, the anti-Jewish laws were introduced. One of the laws that Simone was forced to follow was that she was not allowed to enter certain public places such as parks, cinemas or even stores. She was not even allowed to sit on public benches. Simone was not allowed to enjoy her youth. She did not have the same rights as other French citizens. She had to wear the Jewish star on her clothes whenever she went out. Young Jews who went to school were kept aside so that they could not join in the conversations.

A cousin of Maria’s, Berthe Fridman, remembers going to the Goldbergs’ house at 72, boulevard Saint Marcel, their last address in Paris. Berthe was 12 years old at the time. She remembers that the Goldbergs lived in a store on the first floor, which was both a workplace and a living space. It was a simple home. Simone was not at home, but Berthe remembers Claire and Michèle running around the apartment.

Michèle Goldberg, whose middle name was Charlotte, was born on September 14, 1939 in Paris. Michèle was Simone’s youngest sister.

4. Herszek, Maria, Claire and Michèle’s arrest and deportation.

All of Simone’s family members, except Simone herself, were arrested and interned in Drancy camp. The Goldberg family arrived at Drancy on April 28, 1944. Herszek’s registration number was 20590. He had one thousand three hundred and ninety francs, a gold identity bracelet, a pair of gold and pearl earrings and a gold ring with pink stones on him when he arrived. The family was deported to Auschwitz on April 29, 1944 on Convoy 72. They were probably killed in the gas chambers as soon as they arrived in Auschwitz. Herszek died at the age of 48, Maria at 35, Claire at 11 and Michelle at just 4 years old. They are presumed to have died on May 4, 1944. It was Simone’s birthday.

When her family was arrested, Simone was not at home. She was then sent to a children’s home for young girls on rue Vauquelin, which was run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or General Union of French Jews). An aunt on her mother’s side, Hanna, whose name was Annette Grumberg and who was 18 years old in 1944, went to tell Simone that her parents had been arrested. Annette Grumberg died in 2020. She was able to explain what had happened. Annette says that she heard about the arrest of Simone’s family from a colleague at the post office who helped to take care of the Jewish children in the home on rue Vauquelin in the evening or at night. However, Simone did not want to go home with Annette (they had only known each other for a short time), nor did she want to go into hiding. She returned to her home, but her family had already been taken away. She then went back to rue Vauquelin. Annette says that her biggest regret in life is not having been able to take Simone with her.

5. Louveciennes.

Louveciennes is a town in the Yvelines department, which is in the Île-de-France region of France. In 1944, there was an orphanage there called Séjour de Voisins. It was at 18, rue de la Paix and place Ernest Dreux. It was another UGIF home, home number 56. When their parents were deported, children were sent to the UGIF homes because they were Jewish. The UGIF, which was founded and managed by Jews, was set up at the request of the Nazis in order to monitor the Jewish children and to keep track of where they were.

According to the testimony of Denise Holstein, a Holocaust survivor also deported on Convoy 77 and who was supervisor at Louveciennes, the manager of the home, Mr. Louis, was very selfish because he took the best of the food for himself and his family. The children did not have much to eat, and often ate leftovers. Mr. Louis was also a violent man who abused his power, telling the supervisors to beat the children and not to play with them.

6. The arrest of the children and supervisors at Louveciennes, Drancy camp, and Convoy 77.

On May 9, 1943, the SS officer Aloïs Brunner was posted to Paris to step up the deportation of Jews from France. Between June 1943 and August 1944, he was in charge of Drancy camp, during which time he deported 24,000 Jews. Brunner began his operation to round up the children in the late afternoon of July 20, 1944. It is likely that the failure of the assassination attempt on Hitler that same day contributed to Brunner’s decision.

On 28 July, 1944, Aloïs Brunner gave the order to have the children in Louveciennes arrested. They had a short time to gather a few belongings before the police took them away. The instructors sang songs so they would worry. They were taken to Drancy camp. The children had rooms to sleep in but there were not enough beds everyone, so they had to sleep on the floor. Simone was assigned to staircase 7, along with the other children from Louveciennes. In Drancy, the prisoners were unable to wash themselves, and the living conditions were terrible.

Aboard Convoy 77, which left Drancy on July 31, 1944 the Jews had nothing to drink, regardless of how thirsty they were. The toilets were just a bucket and some straw. They were unable to sit or lie down. The air was barely breathable. The train was made up of cattle cars. When they were on the train, they had no idea where they were going. The journey took 3 days and there were 60 people per wagon. The travelling conditions were horrific. Crammed together for three long days, they went through hell and not everyone survived the journey, sadly.

The older children would say “Pitchipoi” to the younger ones to reassure them. This means “(we are) going to an unknown place”. In Auschwitz, when Simone got out of the cattle car, the Nazis threatened the Jews with dogs, shouted at them to hurry up and were very violent. Simone was selected to go to the gas chamber immediately, probably because she was so young, and she died on August 5, 1944.

Plaque commemorating the children rounded up in Louveciennes.

The arrest of the children of Louveciennes took place shortly after the Allied landings: the Germans were afraid that they would not have time to deport all the Jews before the end of the war.

II. The dialogue.

– Hello

– Hi

– My name is Simone Goldberg, what about you?

– I’m Merveille Siro. How old are you?

– I’m 14. And you?

– I’m 14 too. It’s cool to meet someone my age. Do you have any brothers and sisters?

– Me, I’m my mother and father’s only daughter, but I have half-siblings on both sides. And you, how many brothers and sisters do you have?

– I have two little sisters, Michèle, who’s four and Claire, who’s eleven. Where do you come from?

– My parents are from the Central African Republic. My father was born in Bangui, as was my mother, but a few years after him. And you?

– I’m of Polish descent, from my father, who was born in Szydlowice in 1896 and came to France with my grandparents because of the pogroms. I am also French, from my mother, who was born in the 12th district of Paris in 1909.

– What’s a pogrom?

– It’s a massacre and looting of the Jews by the rest of the population.

– How horrible! But how can that happen in a country against a particular religion?

– I don’t know, but what I do know is that my paternal grandparents, grandmother Hendla and grandfather Chaïm suffered a lot during that pogrom, and they had to flee their country to come here to France with my father.

– Unlike you, my parents came of their own free will, in search of a better life and didn’t experience the same things as your paternal grandparents and your father. I feel sorry for your family.

– It’s nothing, no need to be sorry, it’s not your fault.

– What did your grandparents do for a living in France?

– My grandfather, Chaïm, was a tailor by trade, and he handed it down to my father.

– Are your parents married?

– Yes, they got married in 1929 and had me a year later. And what about you parents?

– No, they separated long before my father died.

– I’m sorry.

– It’s nothing. Is your father French now?

– Yes, he was naturalized in 1933, and one day later, my sister Claire was born.

– Your sister brought them luck and happiness.

– Yes, and are your parents French citizens now?

– My father, yes, he was and for my mother, the procedure is underway. What school do you go to?

– I was in a girls’ school in the 3rd district of Paris, with my sister Claire. I did sewing, like my father. During part of my schooling, from 1939 until now, there was war, France was invaded by the Germans. It meant that my life had to change.

– Why?

– Because Philippe Petain came to power and France capitulated. After that, there came the anti-Jewish laws.

– What were they?

– The anti-Jewish laws said that Jews were not allowed to enter certain public places, whether parks, cinemas or even stores. I was not even allowed to sit on public benches. On top of that, I had to wear a yellow star on my clothes every time I went out. I didn’t see my friends very often.

– They took away your freedom. You couldn’t enjoy your youth or see your friends.

– Yes, and how is your school?

– My school is called Jean de la Fontaine junior high school. It is in the town where I live. It is a mixed school, boys and girls, there is no difference. It is a diverse school, there are lots of people who are different, whether it is the color of their skin, their ethnicity or their religion. It’s a secular school. We are judged for who we are and not for our religion, our skin color or our background.

– How I envy you, I would have loved to live your life. Where do you live?

– I live in Le Mée-sur-Seine, a small town about an hour from Paris. But before I moved to Le Mée-sur-Seine, I grew up in another town, Dijon, about a three-hour drive from Le Mée in the southeast. I lived there until I was eight years old when my father passed away. And you, where do you live?

– I was born in Paris on May 4, 1930 and lived in Nancy with my grandparents before my grandfather, Chaïm, died. Then I came back here in 1937. Before coming to Drancy, an internment camp, I lived on boulevard Saint-Marcel, in Paris, with my family and then in Louveciennes, a UGIF orphanage.

– What?!! you live in an internment camp now? But why? How come you were living in the orphanage when you have parents?

– I’m Jewish, like my parents and grandparents. Because of my religion, my family and I were sent to Drancy, like many other Jewish families in Paris. I was unlucky enough to be interned alone without my family. My mother, father and two sisters were arrested while I was in school and I was sent to Louveciennes, an orphanage.

– Oh, how horrible… that’s not right! I feel sorry for you, that’s anti-Semitism.

– Of course, many other families had the misfortune to be separated and never had the chance to see each other again. Every day I dream of seeing my parents safe and sound.

– You poor thing. I don’t know how to console you. I hope you will see your parents again soon. How was Louveciennes?

– Louveciennes was a very inhospitable place, all the children were lonely. I was one of the oldest children in the orphanage. A lot of the children would sob in the dark, and I couldn’t cry because I didn’t want to make the children sad. Before we came to Drancy, the police came to round us up and we were all put on buses.

– Poor you, I can imagine how you felt. And in Drancy, how it is there?

– Drancy is ten times worse; the living conditions are very primitive, we don’t have much to eat, we are crammed into so-called rooms without being able to go outside very often. Not to mention the director of Drancy, Mr. Aloïs Brunner, a man who has no scruples, he lives just to mistreat us, he doesn’t differentiate between women and children. He has the same fate in store for all of us.

– He is the devil himself! How can a human being have no moral compass? When are you going to get out of Drancy?

– I think I will soon be sent to Pitchipoï, as will the other children who came from Louveciennes.

– What’s Pitchipoï?

– That’s a word they say to reassure us but in fact we don’t know where it is. I don’t think it’s a safe place. It means “a lost hole” in Yiddish.

– How will you leave Drancy?

– We will leave Drancy in cattle trains, in cars where animals like horses are transported. What I do know is that the children who get on these trains never come back. Rumor has it that the children are killed, like their parents. I am afraid that is what will happen to me when I leave this place.

– That’s inhumane, how can humans be crammed into cattle trains?

– Those who do this to us are vile, heartless beings with no conscience. They don’t even deserve to exist; they prey on children, women and elderly people to satisfy their sadistic cravings.

– In my day, we don’t see this kind of thing anymore. Human beings have become aware of the things a man can do.

– You think so?

– Do you have any news from your mother’s family?

– No, since I’ve been here, I haven’t had any news, I think my maternal grandmother, grandma Rosa, is most likely looking for me.

– You must miss her a lot.

– Yes, I miss her very much.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

iL SE trouve que je suis allée moi aussi dans cette école de 6 à 8 ans ! nous habitions alors rue Michel Lecomte …