Simone Bloch

For this biographical work, we have chosen to focus on the journey of two people from Convoy 77, the last convoy of deportees to leave Paris-Drancy for Auschwitz. Their journey before, during and just after the 2nd World War, but also the moment when, during the first decade of the 2000s, it seemed essential to them to do memory work for a wider audience than their family circle. .

The biographies of Simone and Lison Bloch are made in one set, as the two sisters have never been separated in adversity; this is what made their strength during the terrible times of imprisonment, deportation, then confinement in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp (Poland) and finally in the camp of Kratzau (today in the Czech Republic) . It is this “invisible thread of life” that binds them together, which helps them overcome the unspeakable, the appalling inhumanity of the Nazis and their acolytes, and then prompts them to testify about their lives later.

Our history teacher made us study the words of these witnesses of the Shoah; She had the privilege of meeting Simone Bloch (Guinchard) within the framework of educational projects, and told us several times how much she had been struck by her extraordinary capacity for resilience, and by her kindness of soul: often, Simone sought to excuse the behaviour of those who looked unforgivable to us: Pétain sympathizers, whistleblowers, zealous officials who had chosen to exclude Jewish children from swimming pools and regional competitions …

Simone Bloch was born in Strasbourg, Alsace (France) on May 9, 1926; her younger sibling, Lison Bloch, was also born in Strasbourg on March 3, 1928. Their parents were Edmond Bloch, born September 5, 1900 in Lausanne (Switzerland), and Jeanne Bloch, born Brunschwig on April 2, 1902 in Basel (Switzerland). They also had a son, Michel, born August 12, 1930 in Strasbourg.

Edmond and Jeanne Bloch, circa 1920

The whole family is French, and Edmond fought in the ranks of the French army during the First World War. He is very patriotic, and that is why he refuses to settle his family in Switzerland, where his own mother lives, as well as uncles and aunts. He said “I am French before being a Jew“.

Before WWII, the Bloch family lived in Strasbourg, where Edmond was a sales representative. When they were little, Simone and Lison didn’t really face anti-Semitism, but things changed at the end of the 1930s. Lison recalled that “in 1937-1938, we were thrown stones and shouted ‘dirty Jews. “”. She then discovers that she is seen as different, and unwanted.

After the defeat of the French army against the Wehrmacht, in May-June 1940, the Blochs left Alsace and headed south. They first settled in Annemasse in Haute-Savoie, very close to the Swiss border (their grandmother lives near Geneva), then in Aix les Bains, in Savoie, at number 64 Victor Hugo Str eet. It was in this city that they found themselves subject to exclusionary laws targeting Jews, laws enacted by the collaborationist Vichy regime after October 1940.

Simone enjoyed to swim, and practiced swimming at a good sporting level, since she won the Dauphiné Savoie championship at the start of the conflict, and was selected for the French championship! But she was excluded from this competition because she was Jewish.

In Aix les Bains, Simone and Lison, and their brother Michel, go to school normally, and their lives go by with difficulty, of course, but without the fear of being the object of Nazi persecution. Savoie was then occupied by the Italian army, which represented a sort of respite. The situation changed in 1942: in August there was a round-up in Aix targeting foreign Jews. 63 people were arrested and then interned in Ruffieux before being transported to Drancy. On December 30, 1942, all the Jews of Savoie were counted. The Allies’ military landing in Sicily and the collapse of fascist Italy had a disastrous effect on the Jews living in Savoie. At the end of the summer of 1943 the Bloch family left Aix les Bains, where they encountered hostile neighbours who never ceased to see in them “weird people”; Edmond Bloch fears a denunciation. In a carriage, they ascend the Bauges massif to settle in a small remote village, Ecole-en-Bauges.

On September 8, 1943, the Germans took possession of Savoie, after the Italians signed the armistice, followed by the withdrawal of their troops. Shortly after, the Gestapo settled in Chambéry, led several raids in the towns of Savoie, targeting the Jews.

In the village of Ecole, the life of the Bloch family is rather peaceful. They are known under the alias of Blache, but administrative and religious authorities are informed of their status as Jews.

Simone and Lison both have a number tattooed on their arm; the number A16674 for Simone and A16675 for Lison. They were marked at Auschwitz, after being sorted on the train arrival ramp where the Nazis determined they were fit for forced labor.

How did they pass from the tranquility of the remote village of Ecole en Bauges to the barbaric management ways of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp?

Simone, in the early days of Summer 1944, Ecole-en-Bauges, France

In the village, the Blochs were well integrated: the children used to go to school (in 1943-1944, Simone was in 3rd level at the Châtelard college and the sisters rode by bike to the school) ; Edmond took part in agricultural works, helped with hay harvest, and then after played cards with the villagers at the local bar. The whole community knows that they wwere Jewish, but no one mentioned it, they even went to mass to delude if suspicions; they felt rather protected because there were no militiamen or Petainists up there.

It must be noticed that several families in the Bauges sheltered Jewish children during WW2, they were safe there until the end of the conflict.

At the beginning of July 1944, the Nazi forces, several thousand men supported by militiamen, invaded the Bauges mountains: they wanted both to eliminate the Resistance fighters there, and to “rake” the hidden Jews. The Vichy government has planned to round up 100,000 Jews in France, to then deport them eastward as part of the “Final Solution”.

On July 4, the Bloch family was warned of the imminent arrival of the Nazis. They went hiding in the woods above Jarsy, along with another family, the Meyers. Simone and Lison mentioned a nightmare night: it was raining, it was very cold. Early in the following morning, thinking that the Germans were gone, they went back down to the hamlet of Belleville where they understood their mistake: there were lookouts and the locals refused to conceal them. They all hid in a hay barn where they were quickly arrested.

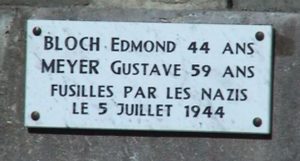

Their arrest on July 5, 1944 in Belleville was a “moment of horror”: they were all lined up against a wall. Then the fathers of both families were shot in the back, and stripped of their goods by the executors. Women and children were taken to Ecole, to the cellars of the Hotel Burgod, where they found Resistance fighters already arrested. They stayed there a night and a whole day, without eating.

Simone and Lison were numb from what they went through earlier. They witnessed the torture inflicted on young resistance fighters from the village. On July 6, Officer Henson, who led the Nazi forces, ordered the execution of 57 Resistance fighters, including 16-year-old twins, and also gave the order to burn down the village of Jarsy, before leaving the scene.

The Jewish prisoners left the village with a military truck towards Chambéry, and were then transferred to the Lyon women’s prison, then on July 22, 1944 to the Drancy camp near Paris.

At the end of July 1944, the Allies had landed in Normandy for more than two months, and their troops gradually liberated France, with the help of the Resistance fighters and the “France Libre” troops. Yet the Nazis and the Vichy authorities continued to deport to the east.

Jail files of Lison Bloch, 1944

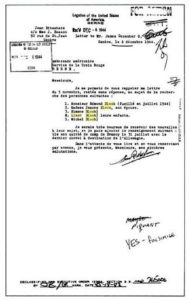

Letter sent by Jean Ditesheim to the United States Embassy in Bern, in December 1944, to learn more about the fate of the Bloch family.

Source: US Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, USA

Jeanne, Michel, Simone and Lison Bloch were part of convoy 77, which left Drancy for Auschwitz in Poland on July 31, 1944. It was the last convoy of “racial” deportees to leave France.

It was a difficult journey lasting several days, in cattle wagons, without food, hygiene or comfort. Arrived on the sorting ramp, the family was separated: Lison and Simone went to the left and Jeanne and Michel went to the right. They were never be seen again.

Simone remembered that in the convoy there were 200 children aged from 2 to 18 from the Rothschild’s orphanage in Paris, who left on the same side as her mom and brother. She said, “Auschwitz is a hell where we arrive still civilized, with baggage, which we are forbidden to take. The dogs are terrifying, the light blinds us, the soldiers use their whips”. Other inmates quickly explained to the two sisters the fate of their mother and brother; they cried for several days.

Simone and Lison stayed three months at Auschwitz- Birkenau, from August 3 to October 28, 1944. They passed three selections made by the evil-looking Doctor Mengele. During these selections they were naked in the cold, with their hands open; they were careful not to get behind each other, to avoid arbitrary sorting. Once, Simone had to fight to get her little sister back, and was badly beaten and humiliated by the guards, but managed to save her.

“The months spent at Auschwitz Birkenau are horror, stupor and idleness; we were in the blocks, we slept 7 in bedsteads on 3 levels, infested with vermin. In the morning, guards scream to get people going to the roll call station. The call lasts 3 to 4 hours, a guard will count us indefinitely, in German, one way and the other. We are in rags, in the cold.

After the call, we were handed an infamous soup and a small piece of bread that was to serve us until the next morning. Then we were usually ordered to transport heavy furniture, sewing machines from one side of the camp to the other, and back again. It was an absurd task.

We were often idle. The main activity was to maintain one’s memory on such and such subject, the names of elevators, cooking recipes. We enjoy talking about cooking because we were so very hungry. We were devastated, resigned, we did not even dare to rise up against the guards. (…) We never washed, we were covered in vermin, we went to disinfection regularly. ”

In October 1944, Simone, Lison and some other inmates were transferred to the Kratzau (now Czech Republic) labour camp to be employed in a weapons factory, in the highly dangerous paint shop. Their living and working conditions were still terrible, but they were given a glass of milk per day.

The Soviet army liberated the camp on May 9, 1945, Simone’s 19th birthday. The war was over in Europe!

Shortly after, they returned to France, to the Hotel Lutétia, where the former deportees were gathered. Their hair was shaved because of the lice crawling on them.

Picture taken when Simone was in Paris, after their return; she declared later « this photo speaks a lot, because I have dead eyes ».

The Bloch sisters were traumatized by everything they have gone through in just a few months, and especially by the loss of their family. Simone learnt that she had her school certificate, which she had passed in Chambéry very few days before their arrest. She quickly found some work to support themselves, as she wanted her little sister, Lison, to go back to school. She said that the deportation and the abominable conditions of their confinement made them “like savages“: she ate with her hands, she blowed her nose in her fingers, she spat on the ground …

Simone and Lison then went to Switzerland for a year, to stay with their aunt Amélie (in fact a great uncle and a great aunt); their aunt was concerned about getting them married quickly, and asked them not to say anything about their concentration camp experience so as “not to suffer from it” but Simone assessed that it was rather because “they could not hear“. From that moment in her life she said “I was angry with the whole world“. She didn’t dare to talk about Auschwitz “at first I was afraid that people would not believe me, the story was so unbelievable. (…) I preferred to keep it quiet. ”

In the 1950s, the two sisters got married: Simone became Mrs Guinchard and converted to Protestantism. Lison became Mrs Malmanche. Both recognized that it was only when their own children were born that they experienced a kind of “rebirth”.

They regularly met with their comrades in misery, the former deportees of Auschwitz and Kratzau. Simone, retired, became a prison visitor at Les Baumettes in Marseille.

It is only in the last part of their life that they began to testify and to share their concentration camp experience, always with the greatest modesty and with kindness. A book “Du rab de vie” and several press articles were devoted to them, as well as a documentary film directed by Isabelle Dupérier “Contre le mur de ma maison”.

Simone meeting students in a high school in Savoie in 2010.

Lison died in 2010 and Simone died in 2013.

NB: all quotes in italics are transcriptions of Simone’s testimonies.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Je suis très ému de lire cette biographie de Simon et Lison, camarades de déportation de ma mère, Régine Skorka Jacubert, avec qui elles ont entetenu une amitié fidèle toute leur vie durant. Le voyage mémoriel de 1993 permit à toutes ces amies, Yvette Lévy et Suzanne Boukobza comprises, de se retrouver à Chrastava, nouveau nom slavisé de Kratzau après la guerre.

Merci beaucoup de votre travail.

Serge JACUBERT

Frère de Serge et en complément de son témoignage, je connais les admirables soeurs Bloch depuis plus de 20 ans car notre maman, l’une des plus âgées du groupe et expérimentées par sa résistance avec son frère Jérôme groupe UJRE de Lyon et leur arrestation par Klaus Barbie, avait pris assez rapidement la “direction” de ce groupe et avait organisé avec le consulat français une réception par la mairie de Chrastava, l’école et l’apposition d’une plaque commémorative. Les enfants tchèques avaient chanté et le journal local avait dédié une page à la cérémonie.

Le groupe de Chrastava se réunissait chaque année le 9 mai en commémoration de la libération du camp par l’armée russe qui avait dans ces rangs de nombreux tchèques.