Sarah HOFFNUNG, 1921 – 2016

Might there be a spelling mistake in the records, between Hoffnung and Hofenung?

Photo of Sarah Hofenung provided by her nephew Didier Norynberg

To begin with, we were not intending to write Sarah’s biography, but, according to the Hofenung family’s naturalization file, Riwka and Leizer had a daughter, Sarah Hofenung.

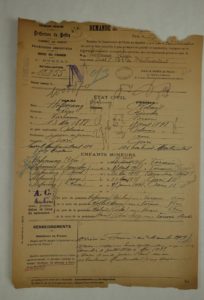

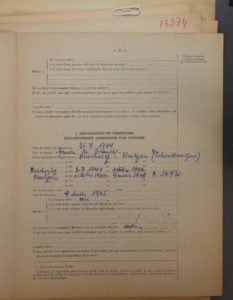

Extract from the family’s naturalization application in 1929

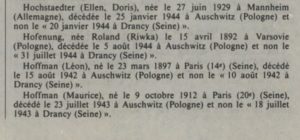

However, on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, it reads Sarah Hoffnung:

Wall of Names

The date and place of birth match, so it must be the same person.

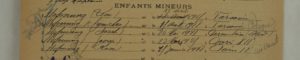

images on microfilms

In the records available to us, there was no indication that Sarah, her sister Rosa or her brother George had any children. In her testimony for the USC Shoah Foundation, Sarah Hofenung said that she had no children. The documents showed that her sister was married to Srul Norynberg and that they lived in Vanves, but they did not mention any children either.

At the Bibliothèque historique des postes et des télécommunications (Historical Library of Post and Telecommunication, on rue Pelleport in Paris, there are many old directories stored on microfilm, in which Srul Norynberg is still listed at the same address in the 1980s.

rue Pelleport avant-guerre

We contacted the Vanves Municipal Archives office and received the following reply:

“Having checked our records, I can confirm that, according to the census of 1962 and 1968, Srul Norynberg, a second-hand goods dealer, his wife Rosa, née Hofenung, and their son Didier Norynberg, born in 1954, were living at 53, boulevard du Lycée in Vanves……… he is mentioned on the copainsdavant website (similar to classmates, friendsreunited etc.) under the heading “schooling” as having attended the Saint Exupéry junior high school in Vanves (1965-1969) and at the Michelet high school in Vanves (1969-1972)”.

Our history and geography teacher then went in search of Didier Norynberg’s phone number. A few clicks later, in the online phonebook and on Facebook, she contacted someone who appeared to be a family member and that person gave her Didier Norynberg’s phone number.

Didier Norynberg, at school in Vanves. Years after this picture was taken, we had the opportunity to interview him!

Some highlights from the transcripts of the students’ interviews with Didier Norynberg, carried out on February 4 and March 11, 2021:

The importance of being a messenger:

- Is it still quite hard to talk about what happened to your family?

- Didier Norynberg : It’s not easy, but now… over the last few years, as I’ve gotten older, I manage to talk about it more, I think. A few years ago, I would have refused to talk about it at all, but now I’m more at ease, plus the fact that I’m passing it on to my children, who started asking me questions when they were in their late teens. That’s when they realized, when they took an interest in their roots, in their family, and in what happened.

- And the fact that a team of students is writing about four members of your family, how do you feel about that?

- Didier Norynberg: I see myself as a messenger, ultimately, for posterity, It really does make a difference, and also there are very few deportees still alive. My parents were deportees, so as their son it’s up to me to play the role of messenger, and, of course, in the end, I appreciate the fact that people are interested in what is a part of French history and perhaps even world history, and I share that interest. We no longer remember these people, they have almost all passed away. They are more than 90 years old now, so there are very few deportees left. It is therefore up to us, the deportees’ sons and daughters, to pass on the message and so it goes on, down the generations. That’s what it comes down to; if we don’t pass on this history, it will be forgotten. We must remember that this tragic episode that took place in France and in other countries was genocide. We must explain why, and discuss what the SS wanted to do, which was to eradicate an entire population based solely on its religion. I really appreciate the fact that you are interested in this.

A son of deportees :

- When did you learn that you were a descendant of deportees and what was your first reaction when you found out?

- Didier Norynberg: I learned about it…oh, I must have been 12 years old to be honest. Before that I was…well, my parents were very protective of me, at least they never talked about it. And even then, even at your age let’s say, they didn’t really talk to me about it.… I was in the youth groups with my cousins… we were very involved in that. Let’s say that we found out for ourselves, you know,……. There were groups in Paris that were dedicated exclusively to people like me….. girls and boys who had had relatives who had suffered during the war, been deported, been deprived, and stuff like that. There was a resource center and also summer camps, there were lots of things like that. And there you have it..

- When you found out that your parents had been deported, were you able to talk about it freely with them or not?

- Didier Norynberg: Didier Norynberg: Yes, I was able to, yes, yes, but I took it little by little because it was very painful for these people to talk about it. Talking about it reminded them of their time in the camp, and they were trying to rebuild their lives and forget all that. You don’t forget such things, but there we are. But still, we try to spare our children sensitive things like that, experiences like that. Maybe we all tend to try to spare our children.

Deportation :

- Did your mother talk to you about this?

- Didier Norynberg: Yes, when she saw that I really….. I was the first one to talk to her about it, not her. She saw that I was interested in it: I’d watched certain movies such as “Nuit et brouillard” (“Night and Fog“) , I’d read Lanzmann’s books, I’d read Elie Wiesel’s books and, well, she explained it to me little by little. She explained to me what happened, that there was a roundup, what we call the roundups, she explained to me that they had to wear the yellow star, that they were turned in and that there was some collaboration on the part of the French. It’s important to say that. There were resistance fighters, but there were also some French who collaborated [with the Germans]. She explained to me about her time in Drancy, how she was loaded into cattle trucks and then headed for the camps, you know. And she explained to me certain things that happened in the camps, some memories that she had about her sister, her friends and her fellow inmates in the camp, and a bit about how it worked between the Nazis and the Wehrmacht. She told me that the Wehrmacht was the Germans, but the military, young people who were called up, whereas the Nazis were a political party to begin with.

- Have you tried to find out what happened to your family?

- Didier Norynberg : I tried, of course, but it’s difficult… My parents didn’t talk about it much, and my family was the same… Well, it was very painful for them, because well, I didn’t go through it, but they did go through it, and they would start crying after two minutes… So, I tried to spare them too… After all, you can see it right away on the websites, when you look for information. I have quite a few documents, I still have some by the way, and there are photos… And in films, for example, you can really see what happened. Afterwards, within my family, yes, I knew, my mother had told me that she was deprived of everything…it was horrible. There was no food, they were treated like animals. They were already on their way after the roundups. They went in cattle cars, as they were called… … Like animals, you know, what they put animals in to move them around. And then women, children, old people, after they were sorted in the camps…you just had to stay alive is what my mother told me, you absolutely had to stay alive. The deportees were very supportive of each other in order to stay alive. That was the only thing they hoped for.

- And Rosa ?

- Didier Norynberg : My mother, well, I think her life stopped when she was deported, and it’s the same with my aunt, because they both came back … first Sarah and then Rosa. I have the impression that their life stopped there. My mother, well, I think her life stopped when she was deported, and it’s the same with my aunt, because they both came back … first Sarah and then Rosa. I have the impression that their life stopped there. And I have little glimpses of youth, yes…here there was a good leather worker… here were their neighbors. My grandparents were quite religious, plus they came from Poland, so they didn’t speak much French. There was a dialect that we Jews of central Europe call Yiddish. It’s a dialect that resembles German somewhat… if anyone does German. They spoke in their language, and of course my parents understood. They spoke it fluently, and so I learned a little bit from my mother and then that was it.

- Do you not feel any resentment towards the Germans?

- Didier Norynberg: No, no. I can’t, because I didn’t experience it, so no, I can’t. Towards the Nazis yes, but not the Germans no; they’re a people, I feel no more resentment towards the Germans than I do towards the French collaborators, who I put on the same level as the Nazis. As for the Vichy government, including Laval and Pétain, I put them on the same level too because they were still French, because they were equally zealous and they participated in the deportation of people, of children… who never came back. So no, I don’t blame the Germans.

- What were the implications for Rosa after the war?

- Didier Norynberg: It followed her everywhere. My mother was, as I always saw her, when in company, laughing and joking, and she hid everything. In private, she was sick, and later on her health was very, very delicate. As she was the youngest, she was the one who suffered the most in the camps, I think, with the deprivation and so on… she didn’t have her period for a year for example… at least, that’s the kind of thing she mentioned. Later on, it caused various illnesses and at the end of her life, due to diabetes, she had to have both her legs amputated. Anyway, she had a very… she died very young, when she was 68 years old …… To begin with, when they came back, they had absolutely nothing, they were people who had been deported. But it must be also be said that after the deportations, many of them never came back at all. The survivors lost half of their family and they came back in circumstances that we’ve spoken about. They were sick, they were living corpses and on top of that, they had lost their homes. It must also be said that they were robbed when they were deported. Their houses were taken from them, their furniture was taken from them, their identity was taken from them; they had nothing left, nothing. They had to rebuild their lives and start again, find somewhere to live and try to live a normal life again. It wasn’t easy but the fact that they had a disabled person’s card at least gave them a few advantages and some recognition. My mother was considered to be 100% disabled.

Life in Paris after the war :

- Didier Norynberg : I know that my grandfather was a leather worker, that was his trade… I know that he was a worker for a while and then I think he had his own small business. So, they were not a wealthy family, and they lived on rue Félix-Terrier in the 20th district of Paris. My mother used to tell me that Django Reinhardt would play guitar in the courtyard and that he would stay there in his trailer…it was the swing era, and the young people would go dancing. They were able to live a little before the deportation, so they did have a few happy moments. As for the rest, they were very quiet, they didn’t have much time.

Antisemitism today :

- What do you think about anti-Semitism nowadays, and also back then?

- Didier Norynberg : I think that for me antisemitism, like racism, is a fear of the other. It’s a failure to find out about the other and I would also say that I believe people always need a scapegoat in life; it’s always someone else’s fault ………… I know that my family arrived during the crisis in ’29 …… And look, I still have this, it’s a residence permit and it says refugee, so there you have it, we were exactly like the refugees who come these days from Lebanon, from Africa, from Mali and from lots of other countries. We were refugees, we were fleeing, we always flee a country because there always have to be scapegoats, such is life., It’s a side of humanity that I don’t like and it’s a shame.… It’s toxic, and me, I try to eliminate it and when I see it, I fight against it. It’s prejudice.

Later on, at the end of the year, this is what Didier Norynberg had to say:

“Not forgotten and not forgiven……At the time of the Russian Empire, my grandparents Leizer and Riwka Hofenung were born in Poland. They fled Poland and the pogroms, and migrated to France, the country of human rights. They went on to have five children, Léon, Symcha, Sarah, Georges and Rosa, my mother. They moved to Boulevard de Ménilmontant and then to rue Félix Terrier. They lived happily in this neighborhood, which was home to many migrants. They brought with them a rich Jewish and Slavic cultural heritage.

They lived through the period of the Popular Front government between 1936 and 1938. They were simple people. My grandfather had a tenor voice like that of Ivan Rebroff, and Georges played the piano, but their happiness was to be cut short. In 1939, the war broke out and continued for five years. Unfortunately they were turned in, arrested by the French militia, transferred to Drancy and then travelled in cattle cars to Birkenau for the Final Solution. My grandmother Riwka was murdered by the SS. Only my mother, who was still a teenager, and my aunt Sarah came back to France, both in a pitiful state. Georges had to endure the Death March, only to die in Dachau. Léon also survived after being interned for seven years in a military camp. My grandfather and Symcha escaped the roundups and made it through.

I, the son of a deportee who once had a family, pass on their story. As for my fight against antisemitism, racism and obscurantism, I shall carry it on as long as I live.

In memory of my family.

June 23, 2021”

History of the family, from Poland to France:

Riwka was born on April 15, 1892 in Warsaw, Poland. She married Leizer Hofenung in her native country, probably in a religious ceremony at the synagogue, but they were remarried in a civil ceremony on December 22, 1925 at the town hall of the 20th district of Paris, on Place Gambetta.

They had 6 children: Léon Hofenung born on September 15, 1915, Symcha (Simon) Hofenung born on April 15, 1918, Sarah Hofenung born on May 24, 1921, Georges Hofenung born on March 23, 1925, Rosa Hofenung born on January 15, 1928 and Jean Hofenung, who was born on October 9, 1932 and died on March 4, 1933 (the year Hitler was appointed Chancellor of Germany). The first two children were born in Poland and the last four in France.

The town hall of the 20th district of Paris, on Place Gambetta, where Riwka and Leizer were married

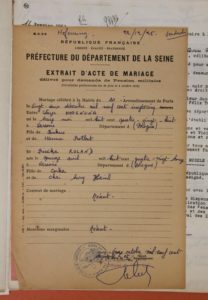

Riwka et Leizer Hofenung’s marriage certificate

Riwka was the daughter of Corka Roland and Chai Sury Hanil. Leizer arrived in France in December 1919, possibly together with Riwka. In 1929, he filed an application for the family to be naturalized as French citizens, which was granted later in the year. In this application he referred to his job as a leather worker, the fact that he served in the Russian army during the First World War and that he was subsequently employed in the Nord Pas de Calais departmental technical service.

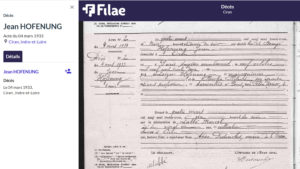

Extract from the Hofenung family’s naturalization application

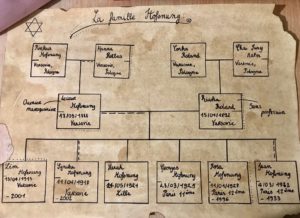

Family trees created by the students:

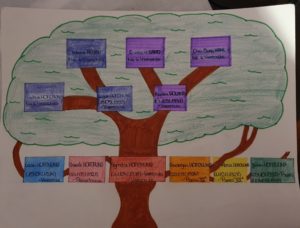

The last child, Jean, who we found on the Filae website, was not mentioned in the documents:

Jean Hofenung’s birth and death records

During the visit to the Shoah Memorial in Drancy in June 2021, the class was able to listen to Sarah’s testimony. Her story was raw, hard-hitting, poignant and touching.

Sarah Hofenung’s testimony for the Visual Shoah Foundation, recorded in 1996, one month after the death of her sister, Rosa

She talks about life in France before the war:

Sarah Hofenung portrays a close-knit family, raised with much love. The family was very poor, as were those of her friends. Her parents were migrants from Warsaw. They hated Poland, a country with a lot of antisemitic violence, and they lived in fear of the indigenous population.

His father, Leizer, came to France after the war and worked for the bomb disposal service near Lille. Her parents had high praise for the people of the north of France, and mentioned how welcoming and cheerful they were. They were not antisemitic.

Her father moved the family to Paris, probably for work. He was a laborer and worked in the leather goods industry. The family first lived in Ménilmontant, where their apartment had no water, electricity or gas. They were still very poor, but happy nevertheless. The town hall of the 20th district of Paris then found them a much more comfortable apartment, but there was still no bathroom. Her parents were very religious and followed kosher dietary principles. Both her father and her brother George believed in the bright future that communism promised. Their communism was a kind of “biblical communism”.

We learned little about Georges’ life from the records. All we discovered is that he was an apprentice mechanic on Boulevard de Charonne in the 20th district of Paris. There are no direct witnesses who can tell us who Georges was or about the things he loved. The only clues to his personality are the words of his sister Sarah, who loved him very much: “He was a wonderful boy, who never turned twenty. George, like his father, “believed in the bright future” promised by communism. Leizer’s communism was a “biblical communism”. Both father and son believed in the goodness of humankind. George said to Sarah: “You know, all men are brothers”.

Arrest and deportation

Sarah Hofenung, whose full name was Sarah Suzanne Hofenung, was born on May 24, 1921 in Pérenchies, a town north of Lille.

At the time of her arrest, Sarah was 23 years old and lived at 2, rue Bailleul in the 1st district of Paris, where she hid, having refused to take part in the census of Jews. Following her arrest, she was interned on rue des Saussaies (after some research, we learned that at there was a Gestapo headquarters at 11, rue des Saussaies).

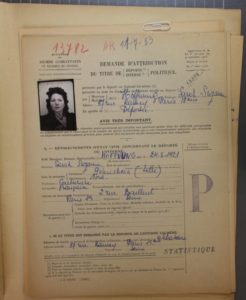

First page of Sarah’s application for political deportee status, from DAVCC archive file

From 1940 to 1944, the headquarters of the Sicherheitspolizei (SIPO) in France was located at 11, rue des Saussaies. It housed the security service (SD), which included Section IV, known as the Gestapo. The SS Obersturmbannführer Kurt Lischka had his office there. Numerous interrogations, including torture, took place in this building. It was later used as the headquarters of the Central Intelligence Service. Today, the building houses the services of the Ministry of the Interior, the General Directorate of the National Police, the General Directorate of the National Gendarmerie and the Central Directorate of the Judicial Police.

According to page 3 of the application for the status of political deportee, the witnesses to the arrest were the building’s concierge and the tenants of 2, rue Bailleul. We also have the witness statements of Riwka Chajut, Elisa Fayer and Germaine Wagensterg, of whom we know nothing more about but who testified that she was arrested by the Gestapo on “racial” grounds.

Page 4 of the application for political deportee status, from DAVCC archive file

The students met Daniel Urbejtel (1) on March 30, 2021. Daniel was deported on the same convoy as Rosa, and he spoke about the environment at the time and about the deportation:

“I have very few memories of the time I spent in Drancy for various reasons, the first of which is that we didn’t stay there for long, but the second is that what happened afterwards is so far beyond imagination that even now I don’t know if I can find the words to describe the indescribable. Still, it was 31 July 1944, a month before the liberation of Paris, when the American landing had already taken place on the Normandy coast. There had already been one in Africa a long time earlier. On 31 July 1944, a convoy was put together, which turned out to be the last large convoy to leave for the East, and on that day the same Parisian buses, but in greater numbers this time, surrounded Drancy and on them we were taken to Bobigny railroad station, a small station used mainly for freight. Bobigny is very near Drancy, so we arrived at the station as a train was being prepared, but I was astonished to discover that it was a train made up of freight cars. I was not aware at the time that we were considered to be freight and not knowing where this train was going to take us, the mere prospect of travelling in a freight car did not bode well. I imagine, but am not sure, that the cargo on each bus was assigned to a particular car. So, I climbed into the car that was I was allocated and I took a walk around. It did not take long, because the car was empty, there was straw on the floor and at one end there were two buckets, one filled with drinking water and the other empty. You can imagine what that one was intended for. And although I was only 13 years old at the time, I wasn’t the youngest. There were pre-school children and there were babies who were crying, crying because even they were shocked by the environment in which they found themselves. The little ones were not fortunate enough to have their caregivers with them. And there were older people in the back who were also crying, and perhaps praying too [……..]. As soon as the doors were closed, they were secured from the outside, and the open section for ventilation was partly blocked by a board that was nailed across the top. This was an understandable attempt to prevent any chance of escape, but the main effect of this was to restrict ventilation, and it was very hot at the beginning of August 1944. At the time, the term “heat wave” did not exist, but it really was extremely hot. And when all the cars were secured, the train began to shake and we set off. Of course, there was no announcement of our destination as is there is these days on French trains. The train just left, and on and on it went. We were locked in that train for three days and three nights, much longer than necessary to travel the 750 miles or so that separated us from the final destination. There was intensive bombing in Europe [………..]. After three days the train stopped for good and the doors opened for the first time. It was then that we realized that we had reached the end of our journey, and that end, alas, was the Auschwitz camp, which I had never even heard of. Auschwitz was an extermination camp as well as a concentration camp. In reality, it was either immediate extermination or extermination through hard labor, but I only discovered that little by little. When the doors were opened, orders were shouted in German, and had to be understood. My brother, who had chosen German as his first foreign language in school, was my translator, and the loudspeakers told us to get out “Schnell, schnell”. Not everyone got off, however. The babies who couldn’t walk stayed on floor in the straw and cried, and people who were not confident about their balance also stayed on the train. I would be like that these days, because now I need a cane to get around. But all those who could stand normally got off, albeit with some difficulty. A few days earlier, it had been quite hard to get in, because the steps were not as low as they are now, and you can imagine how much harder it was to get off when you had to move quickly. If people hadn’t had any space to stretch their legs for three days, and they had to move fast, then if they missed the step, they fell down, and as soon as they fell, dogs came and bit them in the calves. The SS had trained dogs, sheepdogs, as surrogates and this was where the initial selection process took place.”

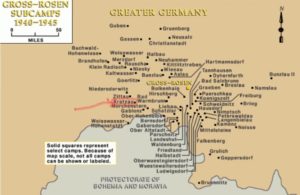

Sarah was deported on July 31, 1944, like Daniel Urbejtel, by cattle train from Drancy to Auschwitz. She arrived in Auschwitz on August 3, 1944 and left in October 1944. Her Birkenau internee number was A.16730. She was then taken to the Kratzau labor camp (in Czechoslovakia) in October 1944. Kratzau was a subcamp of the Gross-Rosen camp (Kratzau is shown by a red arrow on the map)(2)

The Gross-Rosen concentration camp was founded in August 1940 as a sub-camp of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. It was named after the nearby village of Gross-Rosen (now called Rogoznica), located about 40 miles from Wroclaw (formerly Breslau) in the west of present-day Poland. It became an independent camp in May 1941.

Gross-Rosen became the center of an industrial complex and the administrative hub of a vast network of at least 97 subcamps. On June 1, 1945, the Gross-Rosen complex held 76,728 prisoners, including nearly 26,000 women, most of them Jewish. It was one of the largest concentrations of women in the entire Nazi concentration camp system. (1) Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Sarah Hofenung remained there until May 9, 1945, the day of the Liberation.

Life after the war

The application for the status of political deportee was made on July 17, 1953.

Sarah lived at 37, rue Ramey, in the 18th district of Paris (there are several spellings of this street name in the records but this is the most likely). She married Ferdinand Vieux in 1946 and divorced him in 1949. She was a seamstress. She is now recognized as having been a political deportee (according to the administrative specifications of July 7, 1949).

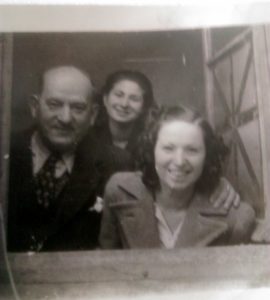

Leizer on the left, Rosa at the back and Sarah on the right

Rosa Hofenung’s wedding in 1952. Rosa is in the front row next to her husband, Srul Norynberg. Sarah is behind Rosa, with Leizer beside her

The students met Daniel Urbejtel (1) on March 30, 2021. Daniel was deported on the same convoy as Rosa, and he spoke about the environment at the time and about the deportation:

“I have very few memories of the time I spent in Drancy for various reasons, the first of which is that we didn’t stay there for long, but the second is that what happened afterwards is so far beyond imagination that even now I don’t know if I can find the words to describe the indescribable. Still, it was 31 July 1944, a month before the liberation of Paris, when the American landing had already taken place on the Normandy coast. There had already been one in Africa a long time earlier. On 31 July 1944, a convoy was put together, which turned out to be the last large convoy to leave for the East, and on that day the same Parisian buses, but in greater numbers this time, surrounded Drancy and on them we were taken to Bobigny railroad station, a small station used mainly for freight. Bobigny is very near Drancy, so we arrived at the station as a train was being prepared, but I was astonished to discover that it was a train made up of freight cars. I was not aware at the time that we were considered to be freight and not knowing where this train was going to take us, the mere prospect of travelling in a freight car did not bode well. I imagine, but am not sure, that the cargo on each bus was assigned to a particular car. So, I climbed into the car that was I was allocated and I took a walk around. It did not take long, because the car was empty, there was straw on the floor and at one end there were two buckets, one filled with drinking water and the other empty. You can imagine what that one was intended for. And although I was only 13 years old at the time, I wasn’t the youngest. There were pre-school children and there were babies who were crying, crying because even they were shocked by the environment in which they found themselves. The little ones were not fortunate enough to have their caregivers with them. And there were older people in the back who were also crying, and perhaps praying too [……..]. As soon as the doors were closed, they were secured from the outside, and the open section for ventilation was partly blocked by a board that was nailed across the top. This was an understandable attempt to prevent any chance of escape, but the main effect of this was to restrict ventilation, and it was very hot at the beginning of August 1944. At the time, the term “heat wave” did not exist, but it really was extremely hot. And when all the cars were secured, the train began to shake and we set off. Of course, there was no announcement of our destination as is there is these days on French trains. The train just left, and on and on it went. We were locked in that train for three days and three nights, much longer than necessary to travel the 750 miles or so that separated us from the final destination. There was intensive bombing in Europe [………..]. After three days the train stopped for good and the doors opened for the first time. It was then that we realized that we had reached the end of our journey, and that end, alas, was the Auschwitz camp, which I had never even heard of. Auschwitz was an extermination camp as well as a concentration camp. In reality, it was either immediate extermination or extermination through hard labor, but I only discovered that little by little. When the doors were opened, orders were shouted in German, and had to be understood. My brother, who had chosen German as his first foreign language in school, was my translator, and the loudspeakers told us to get out “Schnell, schnell”. Not everyone got off, however. The babies who couldn’t walk stayed on floor in the straw and cried, and people who were not confident about their balance also stayed on the train. I would be like that these days, because now I need a cane to get around. But all those who could stand normally got off, albeit with some difficulty. A few days earlier, it had been quite hard to get in, because the steps were not as low as they are now, and you can imagine how much harder it was to get off when you had to move quickly. If people hadn’t had any space to stretch their legs for three days, and they had to move fast, then if they missed the step, they fell down, and as soon as they fell, dogs came and bit them in the calves. The SS had trained dogs, sheepdogs, as surrogates and this was where the initial selection process took place.”

Extract from the 1933 French Journal Officiel

The exhibition of documents and objects kindly loaned to us by the students’ families

A reproduction of a room in a typical apartment of the period

Collection of objects and documents loaned by parents and colleagues

Documents loaned by the students’ parents: photos of prisoners of war and mobilization pamphlets

This project has helped us to better understand what Jewish people have gone through over the years. It has also been an opportunity to commemorate the faces, lives and experiences of the victims, so that we can help to ensure that this never happens again.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

[…] la mère , et ses deux plus jeunes enfants : Georges, 19 ans, et Rosa, 16 ans. Leur soeur aînée , Sarah, a été arrêtée le 20 juillet 1944 par la Gestapo chez des amis où elle se cachait. Seules […]

Bonjour

Je m appelle Simone rozenbaum

Je suis une petite nièce de Louis shlecker époux de Sara honefung soeur de Rosa.

Je cherche à contacter Didier Norynberg

Si quelqu un peut m’aider cela me serait d un grand secours.

Merci

Bonjour, j’ai vu que vous êtes entrée en contact avec Didier Norynberg. Je lui ai transmis des archives que j’avais. Didier Norynberg a mes coordonnées. Cordialement. Danièle Artur.