Marcel DRAÏ, 1926 – ?

Marcel Draï, as drawn by Alexis

We are five students from Bailly-Romainvilliers, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. We were asked by our French and history teachers if we would like to participate in the “Convoy 77” project. We initially chose to research the life of Charles Draï, but we then realized that the rest of his family had also been deported, so as a class, we divided up the task of researching the lives of all the Draï family members. We five focused on the biography of a young Jewish Frenchman of Algerian origin, called Marcel Draï, who had survived the Holocaust. (See the biographies of Berthe, Perlette and Charles)

We wrote this biography from the point of view of Marcel Draï, a young Jewish man who was deported to Auschwitz at the age of 18. It is based on historical sources found on various websites including those of the Shoah Memorial in Paris, Convoy 77, the Paris Archives and Yad Vashem. They enabled us to learn more details about Marcel Draï’s life. In addition, to get a better feel for what life was like for the deportees, we read some of their personal accounts, such as Le journal d’Hélène Berr (Hélène Berr’s diary), Merci d’avoir survécu (Thanks for having survived) by Henri Borlant,

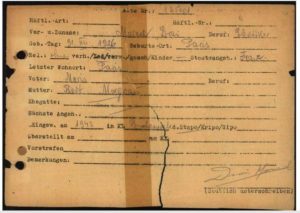

I was born on December 31, 1926 in Paris, France. I lived with my family at 15, rue François Miron in the Saint-Gervais neighborhood of Paris, in the 4th district. I was most likely born at the “Hôtel-Dieu” hospital. I went to the François Couperin junior high school. I was of Algerian origin since my parents were born in Algeria.

I had an older sister called Perlette, who was born on April 24, 1925. I also had three younger brothers, Charles, born on February 19, 1930; Roger, born on April 6, 1933 and Richard, born on April 1, 1939. My mother’s name was Berthe Mourjan, and she was born on February 3, 1902 in Algiers in Algeria, which was at that time a department of France. My father, Moïse Draï was born in Blida, also in Algeria. My mother and father were married there. They then moved to France by boat so that we would have a better life. When they arrived in Paris, they first lived at 25, rue des Blancs Manteaux and then in 1929 they moved to an apartment at 15, rue François Miron, in the 4th district of Paris.

My mother was a seamstress and my father ran a bar. According to my father, we managed to recreate a Jewish community in our neighborhood that was identical to that which my parents had enjoyed in Algeria. It was known as the pletzl, and it enabled my siblings and I to learn more about our cultural background and our origins.

When the war started in September 1939, nothing really changed for us. It was only after June 1940 when the Germans defeated France that things started to change. October 3, 1940 marked the beginning of the end because that was the day our father was ordered to close our bar. We began to have difficulty finding food due to rationing and the limited shopping times for Jews. We made money however we could, doing odd jobs here and there, as well as some short-term employment. At the age of 14, I was already working to help my parents, as was Perlette. Roger and Charles continued to go to school. We were no longer allowed to go to parks and various other places were also forbidden to us. The restrictions were then extended further and we had to return my bicycle and our radio. When the arrests began in 1941, our neighborhood started to feel empty of people, and the police and other officials who helped them were deaf and unsympathetic when we asked questions. We were afraid of being arrested and this made us suspicious of strangers.

On June 8, 1942, it became compulsory for us to wear the yellow star. This had a particular impact on us because people’s opinions of us changed. We felt like undesirables. Papa remained positive but I felt that he was only pretending. I didn’t understand why we were being targeted because of our religion. My parents decided to send us to the free zone, Charles and I first and the two younger ones second, separately, to avoid the possibility of being arrested. The event that affected me the most was our arrest. I was with my little brother and our plan was to cross the demarcation line into free France and thus escape the Germans in the occupied zone. However, things did not go as planned and we were arrested near the town of Rochefoucauld on September 30, 1942. Then we were taken to the prison in Angoulême by the Gestapo. Once there, there was nothing to do and we had to obey the guards if we didn’t want to end up covered in bruises. We were subjected to a brutal interrogation, which included beatings, to try to make us confess that we were Jews. We managed to keep our mouths shut in the end, and about twenty days later, on October 20, 1942, we were released. We then went home and abandoned the whole idea, and to tell the truth, this event added to my fear of the Gestapo and indeed the French militia. When we returned home, my father was arrested, and from then on there were only four of us left at home. My little brothers had succeeded in crossing the demarcation line.

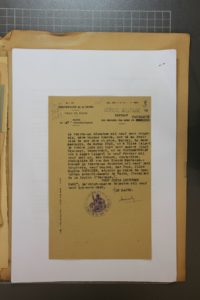

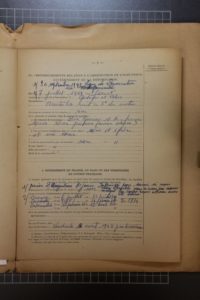

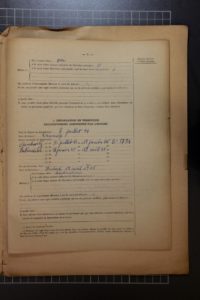

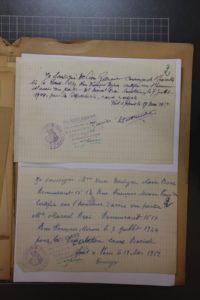

In his application for the status of political deportee in 1952, Marcel himself recounted his arrest as he crossed the demarcation line and the harsh interrogation that followed.

I was arrested by the Gestapo again, on July 7, 1944 when I was in our apartment with my family. In the middle of the night, at 3 a.m., the police knocked loudly on the door. I was dismayed, because the Allied forces had just landed in Normandy and we were arrested so close to the end. The Gestapo acted too quickly, unfortunately. My mother, my sister Perlette and my little brother Charles, resigned to the situation, were put on a bus in front of our building. We were taken to the Drancy internment camp. I saw the vast U-shaped buildings of the “Cité de la Muette”. We soon discovered that the conditions there were appalling, and there was a lack of food and water. I stayed in Drancy for three weeks, from July 7, 1944 to July 31, 1944, when buses came to pick us up and took us to Bobigny railroad station. I was totally disoriented; I hardly knew where we were going or why we were being treated so badly. We were shoved violently into cattle cars and found ourselves crammed in on top of each other in the confined space.

During the trip, I noticed that there were pregnant women, babies, old men and a few families like mine around me. At the beginning, we thought we were going to work but reality soon caught up with us when we realized that could not be true, because the people around me were not fit to work. The hygiene conditions were appalling. We had already been undernourished for a few weeks, and now we had to live for several days with the stench of excrement. Only one bucket was available for our needs, there were about 60 of us and it was impossible to empty it. It was a living hell. It was so hot! The train stopped only once and we were allowed to take a little break to get some fresh air. To get some fresh air? It was more like one breath of fresh air that made us feel better briefly before setting off again. And we still did not know where we were going. People were pushing, grumbling and fighting to get close to the little ventilation slot. Any dignity we had was lost.

Drancy camp

Bobigny station

Cattle cars

J’arrive dans un camp le 3 août 1944, de nuit. Nous descendons du train dans le bruit et les lumières aveuglantes, des chiens aboient et je suis perdu. Les nazis n’arrêtent pas de nous crier « Schnell ! » ce qui veut dire vite en français. Nous sommes séparés en deux files : d’un côté des hommes et quelques jeunes femmes et de l’autre des personnes âgées, des femmes avec enfants. Je m’inquiète pour ma mère et mon frère et j’aperçois au loin ma sœur et ses amies. S’il y a un bon et un mauvais côté, je crains pour le sort de ma mère et de mon frère, ma mère a 43 ans et je ne l’imagine pas travailler dur et Charles n’a que 13 ans.

I and the people in my line were taken to the camp. As we went in, we had to undress to be disinfected and then we were shaved from head to toe to prevent the spread of disease. It took us by surprise when we were then tattooed like animals, and had to put on ragged clothes in random sizes.

The three photos above are from the Auschwitz album. They show some deportees entering the camp, others coming out after having been shaved and some men dressed in striped pajamas. Then were taken by the Nazis when the convoys of Hungarian Jews arrived in the spring of 1944.

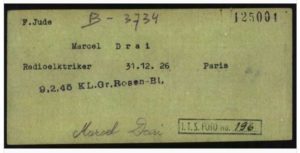

The living conditions in the camp were terrible; we did not have enough food or water and it was unhygienic. The working conditions could not have been harsher. We were totally dehydrated and constantly hungry. The food was inadequate and did not give us enough energy to work. We had a thin soup and a slice of bread, with a little margarine on a good day. The soldiers on guard saw us as a sub-race and showed no mercy: they were sadistic, they hit us and abused us. I saw several of my comrades being beaten to death because they were too weak to continue working. I was regularly hit with a truncheon. There was a particular smell in the camp, which was hard to get used to. It was smoke, which poured constantly from the chimneys at the far end of the camp. Prisoners who had been in the camp longer than us said that the people who were unable to work were killed and their bodies were burned. I tried to remain optimistic about what had happened to my mother and Charles, but it was very difficult. Every morning, we too put the people who had died in the night outside of our hut, and their bodies were sent to be cremated. I was lucky enough to be chosen to be an electrician, so I was spared the hard work outside, which made my day-to-day life a little less difficult and improved my chances of survival.

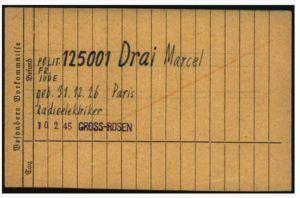

I was transferred by train to a different camp, called Buchenwald, in January 1945. We could sense a certain anxiety among the Germans; they were evacuating the Auschwitz camp before the Allies arrived. We were all assigned to different camps and some people had to leave on foot. I hoped that the bombings would continue to draw nearer and that the Allies would deliver us from this hell. I changed camps again, to Gross-Rosen this time, and was then sent back to Buchenwald. The Americans came to liberate us from Buchenwald on April 13, 1945 – at last!

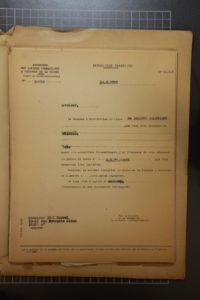

This record shows that Marcel was transferred from Auschwitz to Buchenwald in January 1945. In February, he spent some time in Gross-Rosen, where he worked as a radio electrician. Below are the work record cards from the various camps. He was liberated on April 13, 1945 by the Americans.

I only found out later that on May 8, 1945, the Allies had defeated Nazi Germany, which surrendered and thus brought the Second World War in Europe to an end. And that as of August 25, 1944, Paris had been liberated and the Vichy regime was nothing more than a painful memory.

France was finally free from Germany’s clutches.

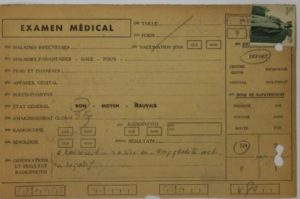

I was then repatriated to the center of Strasbourg on May 16, 1945. I was very weak when I got back and stayed there for several weeks to get back into shape. In the end, although I had lost about 20 pounds, I did not suffer any major after-effects from Auschwitz, unlike many of my companions. Some of them caught pneumonia or typhus and some died.

Once I was well enough to return home, I discovered that my sister Perlette was still alive. This made me both very happy and immensely sad. Very happy because I found out that someone in my family was still alive and that I would finally be able to see her again, but also very sad because I realized that I would never see the rest of my family again. I had imagined myself going home and us being all together again. Once I was well enough to return home, I discovered that my sister Perlette was still alive. This made me both very happy and immensely sad. Happy because I found out that someone in my family was still alive and that I would finally be able to see her again, but also very sad because I realized that I would never see the rest of my family again. I had imagined myself going home and us being all together again. But still, I can’t complain, because in Strasbourg I met a lot of people who had lost everything. Of course, when I saw my sister again, I burst into tears and I promised her that we take over our father’s old bar.

I followed the necessary administrative procedures to have us recognized as victims of war. As a result, many people testified on their honor to having seen me, my little brother, my sister and my mother arrested by the Gestapo in François Miron Street on July 7, 1944, as did the building’s janitor, Léon Garnier, and most likely a neighbor, Marie-Pierre Bouleyre.

In the end, I became a broker. Of course, I kept in touch with my companions from Auschwitz, because when you share your worst moments with someone, it creates a bond. It was very difficult for me to talk about what happened to me, as it brought back bad memories. I could only discuss it with them, and it helped me enormously and made me feel better about what I went through.

On June 21, 1955, I received a payment of 12,000 old francs as compensation for having been a victim of war. I did not like this term because it brought back bad memories, but it was at least an acknowledgement of those hellish years and the liability of the French state.

I was also declared a political deportee on January 14, 1955.

Perlette and I went our separate ways but we remained as close as possible. Perlette got married in 1947 and had her first child, Maurice Pons, named after his father. As for me, I did not want to have children; I was haunted by the trauma of what I had been through and there was no way I would risk letting another child suffer that.

My sister and I took over our father’s old business and tried to maintain the same atmosphere as there was in our father’s time there.

Unfortunately, we do not know what happened next. We lost track of Marcel and we could not find his date of death because we were unable to visit the Paris archives building.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Très beau travail, émouvant, bien écrit et documenté.

Marcel Draï est mort le 7 novembre 1986, à Cannes.Il avait 59 ans.

pour une photo du café Draï après guerre (1946) voir https://jewpop.com/culture/juifs-afrique-du-nord-pletzl-presence-meconnue-epreuves-oubliees/

Le bar Maurice, on y voit Perlette, son mari Raphaël, et Marcel.