Madeleine Édmonde STRAUSS, née GEISMAR

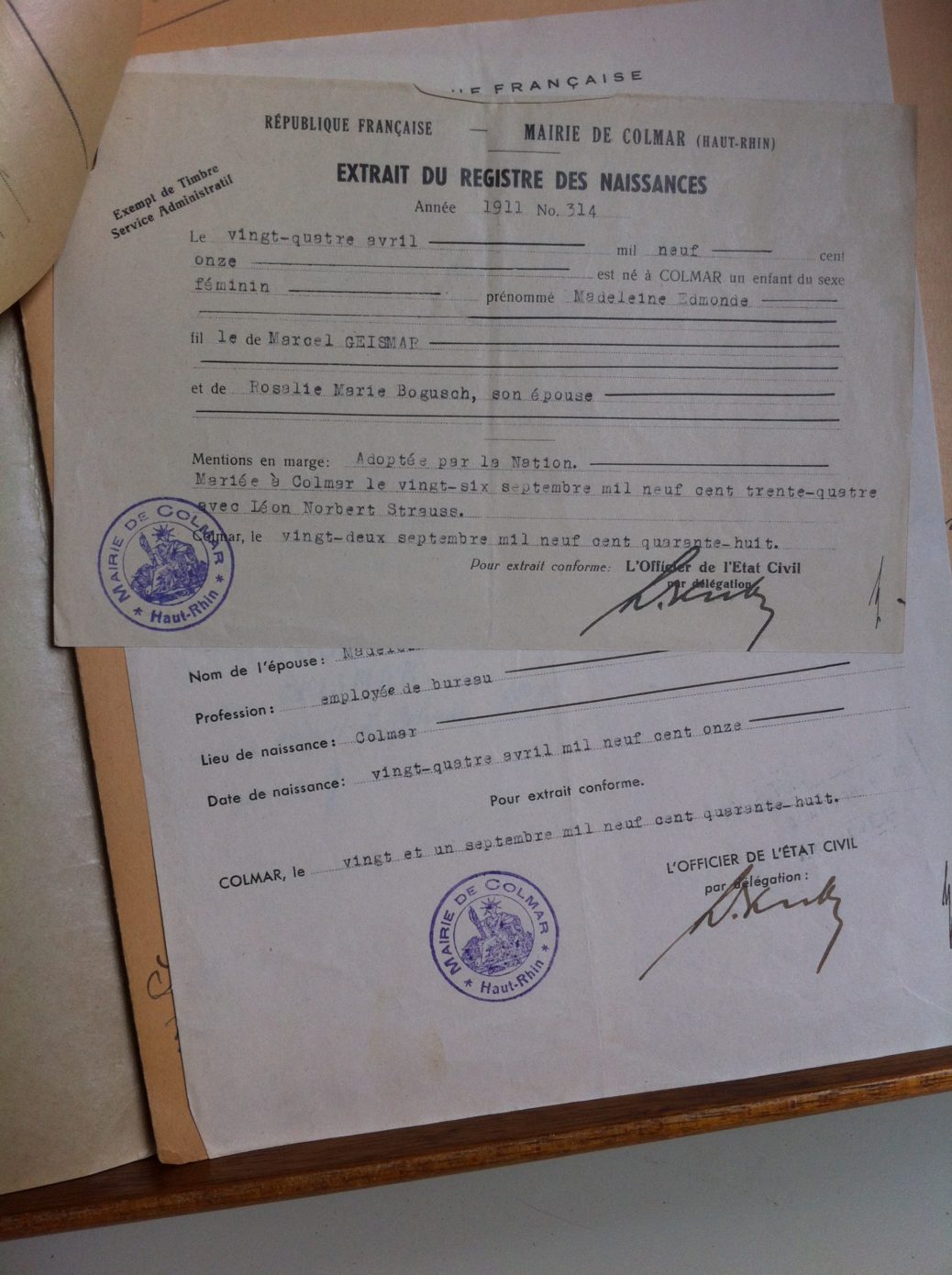

Madeleine’s birth certificate, showing her first name and her second name Édmonde. Unfortunately, we have no photos of Madeleine. Source: Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Historical Research Service in Caen.

This biography was written by Sigrid GAUMEL, Associate Professor of Geography.

In this biography we have tried to trace the personal history of Madeleine Édmonde Strauss née Geismar. We also encourage the reader to refer to the biographies of Léon Norbert Strauss, Lydie Strauss née Zitko, Rosalie Marie Geismar née Bogusch, and Juliette Jeanne Bogusch on the Convoi 77 Association website[1]. These five people, all from the same Jewish family, who lived in Colmar in the Haut-Rhin department, were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944.

Madeleine’s childhood in Colmar in the time of the German Empire (1911-1914)

Madeleine Édmonde Geismar was born on April 24, 1911 at 35 Bärengasse in Colmar[2] She was the only child of Rosalie Marie Geismar née Bogusch, born February 23, 1881 at 14 Neue Strasse in Hanover, in Germany[3] and Marcel Geismar, born September 23, 1878 at 89 Judengasse in Turckheim[4]. Her parents, who were cousins, were married in Colmar on August 8, 1910[5]. Her father, Marcel Geismar, was a merchant[6]. Since the Treaty of Frankfurt, signed on May 10, 1871, the Alsace and Moselle regions of France had been annexed by Germany and had become part of the Reichsland Elsass-Lothringen, thus Gunsbach was, at that time, in Germany.

Madeleine’s paternal grandfather, Jakob Bogusch, was born in 1852 in Grajewo in Russia (now in the north east of Poland), in 1852[7]. He died on October 24, 1912 at 17 Nordstrasse in Colmar[8] at the age of 60. We have found no trace of his grave in the Jewish cemetery in Colmar, nor in any other Jewish cemetery in Alsace[9]. We surmise that Jakob Bogusch was buried in the Jewish cemetery of Colmar but has since been destroyed[10].

After Jakob’s death, Rosalie, her husband Marcel Geismar and their daughter Madeleine went to live with Mélanie and Juliette Bogusch, who was then 27 years old, at 17 Nordstrasse [11]. Mélanie Bogusch née Geismar, born on June 4, 1853 at Turckheim[12] was Madeleine’s maternal grandmother, the widow of Jakob. Juliette Bogusch, born on January 17, 1885 at Gunsbach[13], was Madeleine’s aunt and Rosalie’s younger sister.

Madeleine was made a ward of the state after the First World War (1914-1918)

Madeleine’s father, who enlisted in the German army.

When the First World War broke out, Marcel Geismar, Madeleine’s father, had to don the German army uniform. He was one of 380,000 people from Alsace and Moselle to be called up, 4400 of them being Jewish[14]. He was assigned to a soldier in the 65th infantry regiment and to a battalion of mine-setters (Wehrmann der Minen werferabteilung)[15].

Suffering from grenade wounds, Marcel Geismar was admitted to the German Military Hospital, the Kriegslazarett, in Jarny, which is now in the Meurthe-et-Moselle department of France[16]. This hospital, set up by the Germans in what is now the Alfred Mézières middle school, treated a large number of wounded from the front. With an ophthalmic unit, a dental surgery and several operating theatres, this hospital became an essential part of the German rear line.

Marcel Geismar died there at the age of 38 on April 7, 1917 as a result of his injuries and heart failure[17]. His name is included in the book of names in the German area of the 1914-1918 military cemetery in Colmar[18], as well as on a plaque on the wall of the synagogue in Colmar and on the monument in the Jewish cemetery in Wintzenheim. His grave is in the Jewish cemetery in Colmar.

The bereaved family had its French nationality reinstated.

After the First World War, Alsace-Moselle was returned to France by the Treaty of Versailles of June 28, 1919.

Along with everyone else in Alsace-Moselle, Juliette, Rosalie, Mélanie, and Madeleine waited for the signature of the Treaty of Versailles, then until 1920 for the publication of a decree regarding its application, in order to the process of being “reintegrated into French nationality”[19]. Reinstatement was only granted definitively after approval of an information submitted to the new authorities. These were then entered in reinstatement registers created in each municipality[20]. Mélanie, Rosalie and Juliette were naturalized as French by a judgement made on 28 July, 1920[21].

When her husband Marcel died, Rosalie found herself alone with her daughter Madeleine, aged 6. After the war, Rosalie and Madeleine went to live with Juliette and Mélanie Bogusch, Rosalie’s mother and Madeleine’s grandmother, at 17, rue du Nord in Colmar[22].

Madeleine was accepted as a ward of the Nation by judgment of the Court of First Instance in Colmar on March 11, 1925[23]. Under a law of July 27, 1917 amended by a law of October 26, 1922, the French state adopted orphans where the father (or the family breadwinner) had been killed during the First World War. A decree of July 3, 1923 rendered the legislation applicable in Alsace and Moselle as well, for children of French nationality. Madeleine, as a ward of the Nation, was thereby entitled to protection, material and moral support from the State for her education until she came of age. Unfortunately, we do not have the file relating to Madeleine Geismar’s adoption by the State. The file is not available in the Haut-Rhin departmental archives, suggesting that it may have been lost or destroyed[24].

Madeleine started a family in Colmar between wars.

Madeleine’s grandmother, Mélanie, died at 17, rue du Nord in Colmar, on January 18, 1930[41] at the age of 76. She is buried in the Jewish cemetery Colmar. Her aunt, Juliette, left Colmar for Mulhouse on March 3, 1930[26].

Madeleine, at the age of 23, was married in Colmar on September 26, 1934[27] to Léon Norbert Strauss, who was born November 24, 1907 12 Marktgasse in Obernai[28]. He had a younger brother, Jean Strauss, born October 9, 1910, also at 12 Marktgasse in Obernai[29]. Léon and Jean were the sons of Henri Strauss, born October 20, 1880 in Obernai[30], who was a bank manager[31], and Jeanne Strauss, née Klein. Léon, who was 5’8” tall, had brown hair, gray-blue eyes, a high forehead and a round face[32].

Léon Strauss appears to have lived, from the age of 17, with the Bogusch family, given that on November 10, 1924, he was living at 17, rue du Nord à Colmar[33]. He then did his national service at Mulhouse in 1928, and then, on October 28, 1929, he came back to live with the Bogusch family in Colmar. On August 1st, 1933, he was staying at 4, rue Henner à Colmar.

After they were married, Madeleine and Léon Strauss lived in a second floor apartment 17, rue du Nord in Colmar[34] with Madeleine’s mother, Rosalie. Madeleine was an office worker, a secretary at the Colmar Medical U and Léon was a sales person at Lehmann cuirs, a leather store, in 1936[35]. The 1936 census mentions that Madeleine, Léon and Rosalie were of French nationality and could speak French. Léon was educated to a level equivalent to Sophomore year and held a certificate of musical aptitude and a driving license[36].

Madeleine and Léon Strauss had a daughter, Lydie, although Lydie was not their natural daughter. Lydie, née Zitko, who was born on November 14, 1936 at Wiesbaden in Germany [37], a town about 25 miles from Frankfurt, where Lisbeth Zitko, née Kohn, Lydie’s mother, was living on Otto Strasse[38]. Lydie’s father, Gust(av) Zitko, a travelling merchant with no fixed address, seems to have been absent at the time of her birth. The declaration of her birth was made not by her father but by the office manager of the Wiesbaden hospital, which was at 62 Schwalbacher Strasse. Lydie’s birth certificate has a note on the bottom right, which says: 15/5 1927 Belgrad, Jugosl. Might Lydie and/or her father have been Yugoslavian?

Lydie was taken in by the “NID” in Strasbourg [39], an association or public welfare service that took in orphaned or abandoned children for adoption. We have been unable to find the legal act relating to Lydie Zitko’s adoption[40], and thus do not know the exact date when Lydie arrived at the home of Madeleine and Léon Strauss.

At the end of the 1930s, anti-Semitism was increasing in France. The population, which was suffering from the world economic crisis, political clashes and politico-financial scandals at the time of the Popular Front, turned against the Jews. In Alsace, extreme right-wing organizations and parties called for a boycott of Jewish businesses and distributed anti-Semitic leaflets and newspapers[41]. After the signature of the Munich Agreement, on September 30, 1938, the Jews were accused of inciting France to go to war in order to defend German Jews. Anti-Semitic groups attacked Jewish businesses, particularly in Strasbourg and Mulhouse, breaking windows, ransacking and looting shops and injuring their employees.

At the beginning of April 1938, Rosalie Geismar, Madeleine and Léon Strauss, probably together with Lydie (?), moved to 8, rue Erckmann-Chatrian in Colmar[42] (although, according to the 1938 Colmar town directory, they were still living at 17, rue du Nord in Colmar and, what’s more, in the 1939 Colmar directory, they were not listed at all).

The start of the war and the flight to Cannes and then to Le Cannet, in the Alpes-Maritimes, in 1940.

On the eve of the Second World War, in 1939, about 25,000 Jews were living in the Alsace region, and in January 1940 there were an estimated 6,000 Jewish soldiers in the French army[43]. Among them was Madeleine’s husband, Léon Strauss, who was called up for duty on August 23, 1939 and assigned to the 28th Fortress Infantry Regiment (RIF) stationed on the Maginot line of the Rhine, in the Fortified Sector of Colmar[44].

On September 1, 1939, the German army invaded Poland and then on September 3, France and England declared war on Germany. The inhabitants of all the villages in the Alsace and Moselle regions, near the German border, as well as the city of Strasbourg, were ordered to evacuate. The evacuated area, which became known as the “Front d’Alsace”, or Alsatian Front, was to remain peaceful for eight months. During this “phony war”, the soldiers, such as Léon Strauss, remained in their bunkers on the Maginot Line, waiting for orders and finding things to do.

Madeleine, Lydie and probably Rosalie fled Alsace on September 1, 1939 and took refuge at Eloyes in the Vosges mountains (about 50 miles west of Colmar). They appear to have returned to Colmar on January 15, 1940, to 8, rue Erckmann-Chatrian[45].

On April 6, 1940, Madeleine, along with her mother Rosalie[46], her aunt Juliette Bogusch[47], and her daughter Lydie, fled Alsace for the second time and found refuge in Cannes, in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the south of France. They stayed at 14bis, rue d’Antibes in Cannes[48] [49].

On May 10, 1940, the German army launched an offensive and invaded the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, circumventing the Maginot Line. On May 14, 1940, German tanks entered into France near Sedan, and a month later, on June 14, 1940, Paris was occupied by the Wehrmacht. The 28th Fortress Infantry Regiment were holding the fortified sector at Wolfgantzen, to the north-west of Neuf-Brisach, and Léon Strauss was among them. They were attacked on June 15, 1940 during the German assault on the Rhine. The regiment withdrew under orders, from June 17, 1940 onwards, back towards the Vosges, where the two battalions were finally captured on June 21 and 22, 1940[50]. Léon Strauss was taken prisoner by the Germans on the Maginot Line, but he managed to escape and join his family, probably in Cannes[51].

The family then moved to Le Cannet, a town close to Cannes, although we do not know the exact date on which they moved. Madeleine, Léon, Lydie, as well as Rosalie and Juliette, lived in the Villa Le Bosquet at 6, rue de Madrid in Le Cannet[52], a magnificent villa with a huge garden, where they stayed until June 25, 1944.

The armistice, signed with Germany on June 22, 1940, and with Italy on June 24, 1940, came into force on June 25, 1940. France was divided into two zones: the zone occupied by the Germans in the north, and the so-called “free” zone in the south, controlled by the Vichy government. Alsace-Moselle was effectively annexed and incorporated into the Nazi Reich. The German army occupied this area and established its headquarters there. On July 13, 1940, Robert Wagner, the Gauleiter, the head of the civil authorities in Alsace, decided to expel the remaining Jews in Alsace and to confiscate all of their property, interests and privileges for the benefit of the Reich[53].

More than 3,000 Jews were expelled to the non-occupied zone. Within 3 days, the Nazis had turned Alsace into a Judenrein (German for “cleansed of or free of Jews”) area. The Nazis also sought to erase all traces of the Jewish presence in Alsace. They destroyed or damaged many synagogues, particularly in Strasbourg and Mulhouse, and ransacked Jewish cemeteries, notably the one in Colmar.

Life under the Vichy regime (June 22, 1940 – November 8, 1942), and under the Italian occupation (November 9, 1942 – September 8, 1943).

After the signature of the Armistice by France on June 22nd 1940, the Alpes-Maritimes department was in the southern zone, or Free Zone, where the Vichy regime was in power. Marshal Pétain’s government demonstrated its racist anti-Semitism and declared the existence of a “Jewish race” in the autumn of 1940. On October 3, 1940, it passed a law on the “Status of the Jews,” and on June 2, 1941, it ordered a nationwide census and enacted a second status for Jews. Until the end of 1942, the French State adopted and published more than a hundred legal texts targeting the Jews[54]. It was also actively involved in the deportation of foreign Jews. Jews from Alsace, although they held French nationality, were subject to the Jewish Statute of October 3, 1940. However, the Vichy government did not require Jews in the Free Zone to wear the yellow star.

In response to the Anglo-American landings in North Africa on November 8, 1942, the Germans immediately decided to invade and militarize the Free Zone, leaving the area east of the Rhône to the Italians, including the Alpes-Maritimes department where the Geismar-Bogusch-Strauss family lived. In the departments they controlled, the Italians proved themselves to be sympathetic towards the Jews. There were almost no more arrests, and they even opposed the German and French directives by force, thus putting pressure on the Vichy Prefects not to require the mention of the word “Jew” on identity papers[55]. The Geismar-Bogusch-Strauss family must have benefited from the clemency of the Italians. Lydie Strauss, who was 6 years old in 1942, no doubt went to a school in Le Cannet[56].

The German Occupation (from September 9, 1943), arrests and deportation (July 31, 1944).

Everything changed with the Italian Armistice and the arrival of the Germans on September 8, 1943. The Alpes-Maritimes department, occupied by the Germans until August 1944, ceased to be a safe haven for the Jews. Aloïs Brunner, the Obersturmbannführer (literal translation “senior assault unit leader”) of the SS, arrived in Nice on September 10, 1944 to lead a special commando unit responsible for organizing a systematic hunt for all of the Jews on the Côte d’Azur[57]. Their headquarters, the Hotel Excelsior, near to the Nice train station, was used to assemble and house Jews destined for deportation. Paid informers and “physiognomists” assisted the Gestapo units. They roamed the streets and raided the hotels. All the men were forced to drop their trousers, examined and, if they were circumcised, were immediately arrested[58]. From when Brunner and his men arrived in Nice until their departure in December 1943, about 80 days, 2142 Jews were arrested and registered at the Hotel Excelsior[59].

The fate of Madeleine Strauss, Léon Strauss, Rosalie Geismar and Juliette Bogusch, as well as little Lydie, who was only 7 years old, was later described by Doctor Kruger from Cannes[60], during the trial on June 7, 1945, at the court in Grasse, of the man who denounced the Geismar-Bogusch-Strauss family, a man named Finck. According to Dr. Kruger’s report, the family was arrested on June 25, 1944 and taken to the Villa Montfleury, the Gestapo headquarters in Cannes. On June 27, 1944, the family was transferred to the Excelsior Hotel in Nice, and then, two weeks later, transferred to the Drancy camp, about 2 miles from Paris, in Seine-Saint-Denis.

Drancy was a transit camp, where Jews were assembled before being deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. On arrival at the Drancy camp, the French authorities seized all the internees’ possessions, meticulously filling out a form for each person[33]. A duplicate of the receipts for confiscated valuables was issued by the Jewish service. Usually only one receipt was issued for an entire family. Léon Strauss had 3158 francs confiscated by the administration, as can be seen on the receipt dated July 12, 1944, signed by the “chief of police for Jews” at the Drancy camp[62].

On July 31, 1944, Madeleine, her mother Rosalie, her aunt Juliette, her husband Léon and her daughter Lydie were deported from Drancy to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy 77, as recorded on the original list of those deported[63]. They arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on August 3, 1944.

According to the testimony of another deportee, Albert Broido or Broydo[64], Leon Strauss’ comrade in the Auschwitz camp, it is more than likely that the three women and Lydie, “being pale and suffering,” were immediately transferred by truck to the gas chambers where they were gassed and ultimately incinerated[65]. Rosalie[66], Juliette[67], Madeleine[68] et Lydie[69] all died on August 3, 1944.

Leon Strauss, when he arrived at the station at Auschwitz, walked to the Auschwitz camp [42]. Stripped naked, shorn and tattooed on his left arm (B88 and two unknown numbers), Leon was forced to work for two months in the camp; he was assigned to the kommandos working on street repairs and later on the sewage system. At the end of September, Léon Strauss had an acute finger infection and had to go to the camp infirmary. On October 3, 1944, Leon Strauss was killed in the gas chambers at Birkenau and then incinerated in the crematorium. His death certificate includes the words “Mort pour la France“, i.e. “Died for France” as recommended by the Department of Veterans Affairs on November 28, 1945, which every deportee who was deported due to their race is entitled by law, along with the words “Died during Deportation” in accordance with the recommendation of the Minister of Defense dated September 29, 2003[71].

Madeleine’s relatives, Jean and Henri Strauss.

Jean Strauss, the brother of Madeleine’s husband, Léon Strauss, had been living in the south of Brazil, at Porto Alegre, in the Rio Grande do Sul, since January 24, 1933. From July 16, 1934 to April 10, 1935, he lived in Argentina, at 345 Corrientes Street in Buenos Aires, and then, on April 11, 1935, he settled permanently in Porto Alegre in Brazil[72].

Henri Strauss, the father of Leon and Jean Strauss, took refuge at 211, Francisco Ferrer Street, Porto Alegre, in the home of his younger son Jean. We do not know exactly when Henri settled in Brazil, but the first document that refers to him is dated May 21, 1945[73]). During the Second World War, it was very costly and time-consuming to obtain the visas needed to travel to Portugal and then to Brazil: a French exit visa, Spanish and Portuguese transit visas, an entry visa to America, a minimum fee of $500, and so on[74].

After the war, Henri Strauss embarked on numerous administrative procedures: on May 21, 1945, he wrote to the Ministry of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees in Paris, seeking news of his son, Léon, and his family: “As I have had no news of my eldest son since the occupation of France, I would be grateful if you would be so kind as to inform me of his fate and that of his family”[75]. At that time, Henri Strauss was only aware of a telegram sent by the town hall of Le Cannet, in response to Jean Strauss’ request: “Family Léon Strauss deported in May 1944. No news since.”.

Henri Strauss filed an application on 7 May 1948 with the Civil Court of Grasse, in the Alpes-Maritimes department, and requested the Court, through his Strasbourg lawyers Léon Rapp and Jules Weil, to officially pronounce the deaths of Léon, Madeleine and Rosalie[76]. Juliette’s death certificate had been issued already. In April 1954, Henri asked the French Consulate in Porto Alegre to grant the title of political deportee to his son Léon[77]. His request was granted on March 19, 1955[78], and the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War issued the political deportee card No. 119915058 in the name of Leon Strauss[79]. In September 1955, he received a payment of 12,000 francs from the Department of Veterans Affairs and War Victims [80]. This compensation was paid according to Decree No. 53-103 of February 14, 1953, which granted an allowance to the beneficiaries of deportees or political internees who died while in detention or after repatriation.

In 1959, Henri Strauss and his son Jean Strauss, a trader, who was married to Marianne Cohn lived at 134, rue Cabral in Porto Alegre, in Brazil[81], a street perpendicular to rue Francisco Ferrer where Henri Strauss and his son Jean had lived in the past. These streets are located between the Bom Fim and Branco districts. Bom Fim is well known as the district where the first members of the Jewish community settled in Porto Alegre in the late 1920s.

Jean Strauss died on January 21, 1959 in Porto Alegre, at the age of 48[82]. His father, Henri Strauss, died on July 6, 1960 at the age of 79 on board the Air France plane FBHBH, flight no 095 from Paris via Dakar to Sao Paulo, in Brazil[83]. He is buried in the Jewish cemetery in Bordeaux[84].

Memorial sites and commemorative projects.

Various memorial sites exist to commemorate the deportees. On the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris are the names of Strauss Edmée, de Strauss Léon, de Strauss Lydie, de Bogusch Juliette, et de Geismar Rosalie[85].

The memorial monument at the Jewish cemetery in Colmar mentions the names and ages of the Jewish deportees who lived in Colmar: Strauss-Geismar Madeleine (33 years old), Strauss Léon (38 years old), Strauss (Zitko) Lidy (8 years old), Bogusch Juliette (58 years old), et Geismar-Bogusch Rosa (60 years old). In Mulhouse, the memorial monument at the Jewish cemetery mentions the name of Bogusch Juliette (55 years old). We note the approximate spelling of the first names, and the differing ages of the people named on the monuments.

In the Tivoli gardens in the heart of Le Cannet, a monument was erected on July 1, 2011, near the 1914-1918 and 1939-1945 War Memorials, in memory of the Jewish inhabitants of Le Cannet who were deported between 1942 and 1944. The plaque mentions the names of Léon and Edmée Strauss and their daughter Lydie (8 years old). Once again, the spelling of first and last names is an approximation: Madeleine Edmonde Strauss née Geismar and Lydie Strauss née Zitko. Also, the names of Rosalie Geismar and Juliette Bogusch are not included on this monument. We contacted the Association pour la Mémoire des Enfants Juifs Déportés des Alpes-Maritimes (Association for the Memory of the Jewish people deported from the Alpes-Maritimes) about this and A Mr. Wolman, on behalf of the Association, assured us that the names of Rosalie and Juliette will soon be added on a new commemorative plaque.

The memory of Madeleine Strauss née Geismar, Léon Strauss, Lydie Strauss née Zitko, and Rosalie Geismar née Bogusch, and of Rosalie Geismar née Bogusch, could be further honored by the laying of Stolpersteine outside their last home, 8, rue Erckmann-Chatrian in Colmar.

Notes

We have not mentioned the life of the family of Marcel Geismar’s elder brother, Aron Lazare Geismar. 8 members of the Geismar-Weil-Wolff family, who took refuge in Eymoutiers in the Haute-Vienne department, which is in the Limousin region of France, were rounded up on April 6, 1944 by the SS division commanded by General Brehmer, incarcerated in the Limoges prison, transferred to the Drancy camp on April 12, 1944, and then deported on convoy 72 on April 29, 1944. 7 of them lost their lives there[86].

The life of Henri Strauss’ younger sister, Rosette Neher née Strauss, and her family is recounted in a biographical study by André Neher, Rosette and Albert Neher’s youngest son. In September 1939, the Neher family had to flee Strasbourg and retreated to Dannemarie, to the south-west of Mulhouse. In June 1940, the family, comprising 11 people: Rosette and Albert, their 4 children (Richard, André, Suzanne and Hélène), Richard’s wife Julienne, Hélène’s husband Nathan Samuel and their 3 children, all took refuge in the Limousin, in Brive-la-Gaillarde in the Corrèze department, and then settled in Lanteuil, also in Corrèze. In April 1944, they escaped the round-up carried out by the SS Brehmer division, then in the autumn of 1944, the family moved to Lyon. Albert soon became involved with a children’s home called L’Hirondelle, run by the OSE (Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants, or Children’s Aid Society), which was in the suburbs of Lyon and was managed by his sister Hélène and his brother-in -law, Nathan Samuel. There he befriended the young Elie Wiesel, one of the children in their care. After the Second World War, André Neher became a leading figure in Jewish thinking in France; a philosopher and teacher, he taught at the University of Strasbourg, and then at the University of Tel Aviv in Israel[87].

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ms. Nicole Hermann, daughter-in-law of Ms. Mariette Hermann née Geismar, for allowing me to complete the family tree of the Geismar family. I would also like to thank Mr. Ivan Geismar and Mr. Jacques Geismar and his father.

I am very grateful to Mr. Serge Jacubert and the Association Convoi 77, for providing me with many documents from the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Historical Research Service in Caen.

I would also like to thank Ms. Michèle Merowka, President of the Association for the Memory of Jewish People Deported from the Alpes-Maritimes, an association which aims to put up commemorative plaques in educational establishments, and Mr. Roger Wolman, who provided me with information about the archives available at Le Cannet town hall, and some photographs.

I also thank Mr. Daniel Fuks for sharing work papers and for his help and advice.

Finally, I would like to express my thanks to Ms. Doris Kohl, archivist at the Colmar municipal archives, for her help, advice and the documents provided, and to Mr. Olivier Holder, archivist at the Haut-Rhin departmental archives, for his assistance and his availability. Lastly, thanks to Mr. Martin Gugg, a German teacher, for his linguistic assistance.

Biography completed on April 5, 2020.

References

[1] The spelling of people’s surnames and first names changes according to the documents of the German authorities (between 1871 and 1918) and the French authorities (after 1918), and according to the authors and sources of the documents. For example, with regard to the documents of the French authorities, Madeleine Edmonde Geismar is sometimes mentioned as Madeleine Edmée Geismar, Rosalie Marie Geismar married name Bogusch, as in Rosa Geismar- Bogusch or Rose Geismar, Juliette Jeanne Bogusch as Jeanne Juliette Bogusch or Julie Bogusch and Lydie Strauss née Zitko as Lidy Strauss.

[2] Birth certificate of Madeleine Édmonde Geismar, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[3] Birth certificate of Rosalie Bogusch, Stadtarchiv Hannover, available on the Yad Vashem website.

[4] Birth certificate of Marcel Geismar, Haut-Rhin Departmental Archives, reference N 1873-1882 Turckheim 5Mi 499/4.

[5] Marriage certificate of Rosalie Bogusch and Marcel Geismar, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[6] Mention of Geismar Marcel, Kaufmann. Adressbuch der Stadt Colmar, 1911/1912, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[7] According to the death certificate of Jacques Bogusch, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[8] Death certificate of Jakob Bogusch, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[9] According to the website of the Jewish community in Alsace and Lorraine: http://judaisme.sdv.fr/. The name of Yentel Bogusch is mentioned in the Jewish cemetery in Colmar, but we have not been able to establish a definite family link between Yentel and Jakob Bogusch.

[10] The Jewish cemetery in Colmar was ransacked during the Second World War. The graves were ripped out by stonecutters and reused to pave the streets or build anti-tank barriers, according to Mireille Biret, “Le sort des Juifs d’Alsace pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale”, Base Numérique du Patrimoine d’Alsace, Canopé, Académie de Strasbourg, 2011 (online at http://crdp-strasbourg.fr).

[11] Mention of Geismar Marcel, Kaufmann, Nordstr. 17. Adressbuch der Stadt Colmar, 1913/1914, et 1914/1915, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[12] Birth certificate of Mélanie Geismar, Haut-Rhin Departmental Archives, reference N 1850-1862 Turckheim 5Mi 503/7.

[13] Birth certificate of Juliette Jeanne Bogusch, Haut-Rhin Departmental Archives, reference N 1883-1892 Gunsbach 5Mi EC121; Birth certificate of Juliette Jeanne Bogusch, Gunsbach Municipal Archives.

[14] Philippe Landau, 1871-1918 Les citoyennetés à l’épreuve, in sous la dir. de Freddy Raphaël, Juifs d’Alsace au XXe siècle, ni ghettoïsation, ni assimilation, Strasbourg, La Nuée Bleue, 2014.

[15] Death certificate of Marcel Geismar, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[16] Kévin Goeuriot, « Jarny pendant la Grande Guerre », Jarny Patrimoine, n° 8, Supplément Jarny Mag, juillet 2014.

[17] Death certificate of Marcel Geismar, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[18] Namenbuch, Deutscher Soldatenfriedhof 1914-1918 – Aufgestellt von der Deutschen Dienststelle (WAst) Berlin in Zusammenarbeit mit dem Volksbund Deutsche Kriegsgräberfürsorge.

[19] Bernard Wittmann, Une épuration ethnique à la française, Alsace-Moselle 1918-1922, Fouesnant, Yoran Embanner, 2016.

[20] After 1945, for administrative purposes, Henri Strauss had to prove “possession of the status of French nationality” for Léon Strauss and Juliette Bogusch (and probably also Rosalie Geismar and Madeleine Strauss). We thus have a copy of the extract from the register of persons with full rights as a French citizen dated August 9, 1920 for Léon Strauss (certified copy dated March 10, 1954) and a certificate of nationality for Juliette Bogusch, dated December 17, 1947). Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[21] Address records of Marcel Geismar and Jakob Bogusch, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[22] Colmar town directories of 1920, 1921, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929 and 1932, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[23] Adoption judgement for Madeleine Édmonde Geismar from the Court of the First Instance in Colmar, Haut-Rhin Departmental Archives, AL 97185.

[24] Document consulted at the Haut-Rhin Departmental Archives, reference 17AL2/841.

[25] Death certificate of Mélanie Bogusch née Geismar, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[26] Address record for Juliette Bogusch, Mulhouse Municipal Archives.

[27] Marriage certificate of Madeleine Geismar and Léon Strauss, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[28] Birth certificate of Léon Strauss, Bas-Rhin Departmental Archives (online), reference 4E348/55.

[29] Birth certificate of Jean Strauss, Bas-Rhin Departmental Archives (online), reference 4E348/55.

[30] Birth certificate of Henri Strauss, Bas-Rhin Departmental Archives (online), reference 4E348/39.

[31] Letter dated May 7, 1948 from the lawyers Maîtres Léon Rapp and Jules Weil to the Court at Grasse. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[32] Ministry of War, subdivision of Sélestat, register number, class of 1927, 3rd volume, Leon Strauss identification number 1146. Bas-Rhin Departmental Archives, reference 806D20.

[33] Address record for Léon Strauss, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[34] Colmar town directories for the years 1936, 1937, and 1938, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[35] 1936 census of Colmar, Haut-Rhin Departmental Archives.

[36] Ministry of War, subdivision of Sélestat, register number, class of 1927, 3rd volume, Leon Strauss identification number 1146. Bas-Rhin Departmental Archives, reference 806D20.

[37] Birth certificate of Lydie Zitko, Municipal Archives of Wiesbaden, in Germany.

[38] The first names of Lydie Zitko’s parents are approximative due to the illegibility of Lydie Zitko’s birth certificate, Municipal Archives of Wiesbaden, in Germany.

[39] According to the witness statement of Ms. Mariette Hermann, dated 22.10.1991, available on the Yad Vashem website.

[40] Documents consulted: register of acts required to be registered at the Tribunal de Première Instance in Colmar, business register O, P, Q, Z of the 1st chamber of 1934 to August 1941, Haut-Rhin departmental archives, AL125082; register of acts required to be registered at the Tribunal de Grande Instance in Saverne, alphabetical list of cases of the 1st civil chamber from 1903 to 1953, Departmental Archives of the, 2044W7; register of acts required to be registered at the Tribunal de Grande Instance de Strasbourg, alphabetical list of cases of the 1st civil chamber 1932 to 1944, Departmental Archives of the, 811D7, 811D8, 811D9 ; register of acts required to be registered at the Tribunal de Grande Instance de Strasbourg, alphabetical list of cases of the 2nd civil chamber of 1937 to 1939, Departmental Archives of the Bas-Rhin, 812D9 ; register of acts required to be registered at the Tribunal de Grande Instance in Strasbourg, alphabetical list of cases of the 3rd civil chamber of 1933 to 1939, Departmental Archives of the Bas-Rhin, 813D31.

[41] Freddy Raphaël, Les Juifs d’Alsace et de Lorraine de 1870 à nos jours, Paris, Albin Michel, 2018.

[42] Address record for Léon Strauss, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[43] Jean Daltroff, “Paroles de combattants et de prisonniers de guerre 1939-1945” under the direction of Freddy Raphaël, Juifs d’Alsace au XXe siècle, ni ghettoïsation, ni assimilation, Strasbourg, La Nuée Bleue, 2014.

[44] Ministry of War, Sélestat Subdivision, registry entry, year 1927, 3rd volume, registration number of Léon Strauss, 1146, Departmental Archives of Bas-Rhin, 806D20.

[45] Address record for Léon Strauss, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[46] Address record for Rosalie Geismar, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[47] Address record for Juliette Bogusch, Mulhouse Municipal Archives.

[48] Address record for Léon Strauss, Colmar Municipal Archives.

[49] According to Mr. Roger Wolman, the number 14bis, rue d’Antibes does not or no longer exists now (June 2019). The numbers 14 and 16 have succeeded it.

[50] According to the website: www.memorialgenweb.org.

[51] Letter dated May 21, 1945 from Henri Strauss to the Ministry for Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees in Paris. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[52] Death certificates of Léon Norbert Strauss and Madeleine Edmonde Geismar dated 13.12.1948, Le Cannet town records; Death certificate of Lydie Strauss dated 03.05.2013, Le Cannet town records; Death certificate of Rosalie Marie Bogusch dated 06.01.1949, Le Cannet town records; letter from lawyers Maîtres Léon Rapp and Jules Weil of October 6, 1947 to the State Prosecutor.

[53] In July 1940, the two heads of the civil administration, Robert Wagner in Alsace and Joseph Bürckel in Moselle, decided to rid Alsace-Moselle of all the “undesirable elements” unworthy of populating Germanic lands: Jews, gypsies, criminals and the incurable. The French and Welschisants were to be expelled to the unoccupied zone. The Jews of Alsace-Moselle had between one and twenty-four hours to prepare for their departure and could only take with them a 45-65lb suitcase and a small amount of money. From Freddy Raphaël: Les Juifs d’Alsace et de Lorraine de 1870 à nos jours, Paris, Albin Michel, 2018.

[54] Jean Kleinmann, “Les politiques antisémites dans les Alpes-Maritimes de 1938 à 1944” Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 74, 2007 (online).

[55] Jacques Semelin, La survie des juifs en France 1940-1944, Paris, CNRS Editions, 2018.

[56] According to Ms Michèle Merowka, President of the Association for the memory of Jewish people in the Alpes-Maritimes, we cannot find out where Lydie Strauss went to school due to lack of school records in the Le Cannet.

[57] Jean Kleinmann, “Les politiques antisémites dans les Alpes-Maritimes de 1938 à 1944”, Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 74, 2007 (en ligne).

[58] Renée Poznanski, Les Juifs en France pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale, Paris, CNRS Editions, 2018.

[59] Jean Kleinmann, “Les politiques antisémites dans les Alpes-Maritimes de 1938 à 1944” Cahiers de la Méditerranée, 74, 2007 (online).

[60] Jacky Dreyfus and Daniel Fuks, Le Mémorial des Juifs du Haut-Rhin, Martyrs de la Shoah, Strasbourg, Jérôme Do Bentzinger, 2006.

[61] Annette Wieviorka and Michel Laffitte, A l’intérieur du camp de Drancy, Paris, Perrin, 2015.

[62] Receipt in the name of Mr. Strauss, Drancy search logbook No 156, receipt No 6441, available on the website of the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

[63] Original list of the deportation convoy available on the website of the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

[64] Albert Broido or Broydo was born in 1905. Arrested on June 27, 1944 and deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, his left arm was tattooed with the number B 3705. He was returned from Buchenwald on April 21, 1945. He was living at, 11 rue du Trésor in Paris in June 1945, and then at 33, Boulevard Saint-Martin in July 1947.

[65] Jacky Dreyfus and Daniel Fuks, Le Mémorial des Juifs du Haut-Rhin, Martyrs de la Shoah, Strasbourg, Jérôme Do Bentzinger, 2006.

[66] Death certificate of Rosalie Marie Bogusch dated 06.01.1949, Le Cannet town records.

[67] According to the note on the birth certificate of Juliette Jeanne Bogusch, Municipal Archives of Gunsbach. The Le Cannet town records department has not issued, to date, a death certificate for Juliette Bogusch.

[68] Death certificate of Madeleine Édmonde Geismar dated 13.12.1948, Le Cannet town records.

[69] Death certificate of Lydie Strauss dated 03.05.2013, Le Cannet town records.

[70] Jacky Dreyfus and Daniel Fuks, Le Mémorial des Juifs du Haut-Rhin, Martyrs de la Shoah, Strasbourg, Jérôme Do Bentzinger, 2006.

[71] Death certificate of Léon Norbert Strauss dated 13.12.1948, Le Cannet town records.

[72] Ministry of War, Sélestat Subdivision, registry entry, year 1930, 4th volume, registration number of Jean Strauss, 1610, Departmental Archives of Bas-Rhin, 817D10.

[73] Letter dated May 2, 1945 from Henri Strauss to the Minister of Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees in Paris. PAVCC, SHD, Caen (document obtenu par l’intermédiaire de l’association Convoi 77).

[74] Jean-Louis Panicacci, “Les juifs et la question juive dans les Alpes-Maritimes de 1939 à 1945”, 85 p. (online).

[75] Letter dated May 21, 1945 from Henri Strauss to the Ministry for Prisoners, Deportees and Refugees in Paris. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[76] Letter dated May 7, 1948 from the lawyers Léon Rapp and Jules Weil to the Civil Court in Grasse. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[77] Letter dated April 10, 1954 from Pierre Martin, French Consul in Porto Alegre, to the Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[78] Letter dated March 19, 1955 from the Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War to Henri Strauss. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[79] Political deportee card No. 119915058 in the name of Léon Strauss. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[80] Payment slip, from the Ministry of Veterans Affairs and War Victims, for the payment of the deportees’ survivors’ allowance to political internees who died while in detention or after repatriation, sent to Henri Strauss on September 15, 1955. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts dept., Historical Service of the Department of Defense, Caen (document obtained through the Convoi 77 association).

[81] Copy of the death certificate of Jean Strauss, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, central civil status department.

[82] Copy of the death certificate of Jean Strauss, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, central civil status department.

[83] Death certificate of Henri Strauss, municipality of Mérignac, in the Gironde department.

[84] Website of the Jewish cemetery in Bordeaux: www.cimetiereisraelitebordeaux.com/.

[85] Inscription on the Wall of Names. Website of the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

[86] Witness statement of Françoise Azoulay, Jeanne Geismar’s daughter, in Jacky Dreyfus and Daniel Fuks, Le Mémorial des Juifs du Haut-Rhin, Martyrs de la Shoah, Strasbourg, Jérôme Do Bentzinger, 2006.

[87] Sandrine Szwarc, “André Neher, philosophe, exégète, enseignant (Obernai, Bas-Rhin, 22 octobre 1914 – Jérusalem, 23 octobre 1988)” Archives juives, vol. 42, 2009/2, p. 140-145. Online on Cairn.info.

Contributor(s)

Sigrid GAUMEL, Associate Professor of Geography.

Français

Français Polski

Polski