The shattered life of Laure COHEN

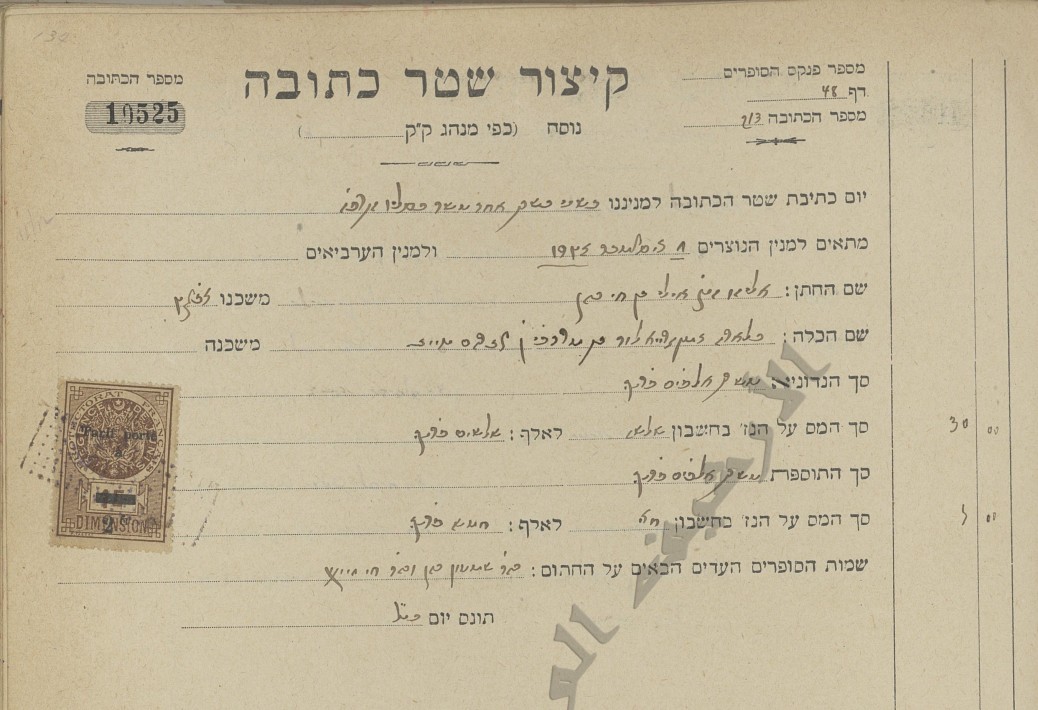

(opposite: photo of her marriage license)

by Danielle Laguillon Hentati

Honorary Professor of Italian and author honored with the Palmes académiques

Even though it was a hard task, Odette felt so mordantly what she had just lived through that she wrote and made drawings from the moment of her liberation, so as to be certain to stay as close as possible to the reality, so afraid was she that time would modify and deform her memories, either softening them or on the contrary making them blacker.[1]

Unlike Odette, Laure never came back from Auschwitz. She never testified. She fell into total oblivion. She is not on the list of victims at the Yad Vashem Memorial.

When the Second World War broke out, no one suspected that it was to be the most murderous military conflict in history. And few observers could predict the repercussions on the civilian populations. The human cost was catastrophic: between 60 and 80 million dead, among whom were 45 million civilians, plus many millions wounded, 30 million Europeans displaced.

While the bombings, executions, reprisals were to contribute to the horror of the war, it was most specially the concentration and extermination camps that would arouse general revulsion for the way they were conceived to provide the methodic extermination of all the “enemies of the Reich” — Blacks, Gypsies, Slavs, Jews. The eradication became massive in 1944.

In Tunisia

When Clara Taieb[2] was born on February 20, 1895 at Sfax, a town located on the edge of southern Tunisia, her parents certainly planned for her to have a quiet life in or near her hometown.

Her father’s family were Tunisian Jews, known as Twansa, and little is known of it. Her father, Mordekhai (called Mardochée by the family), the son of a certain Avraham, was a traveling trader. Her mother’s family came from Leghorn in Italy. Her mother, Sarah Ossona (sometimes erroneously given as Assoua), was born in Tunis in 1866 to a merchant, Jacob Mendès-Ossona (1822 – 1902), and Clara Cardoso (1834 – 1904). She died on February 15, 1903 in Tunis when her little girl Clara was eight years old. Clara, whom the family called Laure, had a brother named Albert, to whom she was to remain deeply attached.

Although they were Tunisian, they were declared “under French protection”. The situation of Jewish citizens in Tunisia was different from that of their fellow Jews in Algeria, which was part of France and whose inhabitants were granted French citizenship by the Crémieux Decree. The Tunis Regency was a protectorate whose people kept their Tunisian nationality unless they requested naturalization. Nevertheless, at their request, the citizens of Israelite confession (as they were then called) were placed under the juridical protection of France.

Laure was therefore brought up between the Twansa and the Grana, at the crossroads between the religions and cultures of Tunisia, cosmopolitan since the 18th century. [Incompréhensible sans expliquer les termes, peut-être dans une note.]

In Tunis on December 8, 1924 Laure married Eliahou (called Élie) Cohen, born on December 13, 1882 in Tunis. His father was named Hai. The marriage was a religious rather than a civil ceremony, performed by a rabbi notary.

Soon thereafter the couple left Tunisia for France. All her close relatives were dead and Laure was distressed that she could no longer follow the custom of visiting their graves in the Borgel cemetery on the anniversary of their deaths and the feast of Roch Hachana. [besoin de note] Still, she hoped this would be the start of a new life with her husband, and that circumstances would allow her to return to Tunis one day, at least to go and pray by their gravesides.

From Strasburg to Villeurbanne

The couple settled in Strasburg, where their only child, Roger Hai, was born on August 14, 1928. He was declared by his mother, and then on September 4, 1928[4] recognized by his parents, a formal obligation in the absence of a civil marriage.

Did Laure feel isolated in Strasburg, far from her brother Albert, despite the presence of her nephew, Abraham Albert Boucara? Was she without a social life? The fact is that around 1935 she and her family moved to Villeurbanne, near Albert and his wife Adrienne.

What an odd couple! He was as short and skinny and she was tall and plump. She had striking red hair. It was said to be a marriage of love. Their daughters, Sarah and Renée, are my best friends.[5]

Albert was the manager of Élie Boccara’s company[6] in Lyon. Élie Cohen was hired to work for the same company[7].

The family resided at n° 58 rue Hippolyte Kahn in Villeurbanne, a rapidly expanding working-class town on the edge of Lyon. On that quiet street lived low-income tradesmen and employees, both French and foreign. There were Spaniards, Italians, Turks, Polish, Russians[8]. Coexistence between the different nationalities was not a problem in this suburb that had become cosmopolitan since the arrival of workers from the colonies and foreign lands, laborers already indispensible to economic development during the war of 1914-1918, when companies in Lyon and others that had fallen back from invaded territory began to manufacture radio equipment and various subcontractors innovated in the field of electric components for the automobile industry.

Laure was happy in her house near the brand-new neighborhood of Gratteciel fostered by the Socialist mayor, Lazare Goujon. Running on the strength of his record as a builder, this physician-hygienist expected to be reelected mayor in 1935, but he was defeated by a teacher, the Communist candidate, Camille Joly. [9]

Doubtless little interested in politics, Laure took care of her house and her son. She was an accomplished housewife who shared with her husband Élie a love of family. They gladly entertained all their relatives:

The other Sundays were spent at Laure Cohen’s, the sister of Albert Taïeb. Her son Roger had marvelous toys and an amazing electric train we admired greatly. His father Élie worked for Papa, who never gave us such fine presents! Laure liked to go on about how handsome and smart her wonderful son was.[10]

Like any good Mediterranean mother she focused all her love on this only son who fulfilled all her expectations. She enjoyed this trouble-free existence until the year 1939 put an end to it.

First came the ill omen of a local rupture. The Communist municipality of Villeurbanne was dissolved when the French Communist Part was banned by the Daladier Decree of September 26, 1939. The Prefect appointed Victor Subit as president of a special delegation. Then in 1941 he was replaced by Paul Chabert, named mayor by Vichy and who was to boast of being the first mayor “to materialize his homage to the Maréchal de France [Pétain] with a bust worthy of the great leader”.[11].

Another, more tragic event was the outbreak of the war. During the invasion Lyon saw no fighting, as its mayor, Édouard Herriot, had obtained the status of an open city for the agglomeration. The Germans did not long remain, and a great many refugees came to Lyon as of July 1940. The city and its neighboring agglomerations were subject to the same common political existence, made up of censorship and official propaganda, as the rest of France under the authority of the Vichy government, which had just published the Statute on the Jews. It was valid throughout French territory, as well as in the colonies and protectorates, raising anti-Semitism to the status of state policy. Reacting to the Vichy policy, a rich network of resistance agents embracing all political shades quickly founded a large number of movements and clandestine newspapers.

“They have landed in North Africa!”

That was the wonderful news that greeted us on November 8, 1944. The landing took place in Morocco and Algeria. On the London radio we followed the combat between the Allied and Vichy forces. Collaboration France railed against the invasion of our colonies.

It was also Robert’s twelfth birthday. Uncle Jo, Armand and Tary, Charles and Lucienne, Albert and Dédée all came to drink champagne. We laughed, we sang, merry as prisoners about to be freed. They would soon be landing in France. Dates and places were postulated. In a few months the situation was reversed. Rommel was routed in Africa. The Russians were holding out before Stalingrad. Victory was for tomorrow.

The awakening was to be brutal.[12]

From Montluc Prison to Auschwitz

On November 11, 1942 the town of Villeurbanne, along with all the rest of the Free Zone, was occupied by German troops. It was the time of terrorist attacks, executions, assassinations and despoliations. It was the time of roundups for the impressment of “able-bodied prisoners”, as on March 1, 1943 in Villeurbanne, for as the war was prolonged and intensified Germany henceforth lacked workers to keep its war industry functioning smoothly. It was the time of roundups and denunciations of the “enemies of the Reich” and the communities to be wiped out, such as the Jews, who were blamed for all evils.

Laure and her family nevertheless stayed in Villeurbanne, as did Albert. They felt safe in this workers’ suburb where solidarity was not a vain word.

Meanwhile the city of Lyon suffered stringent repression due both to the size of local resistance groups and to its being a regional center for the Germans’ agencies of repression (Gestapo, SS, and military police) and for the French Militia. On November 20, 1943 members of the family began to be arrested, and this went on until June 26, 1944.

On Wednesday, July 5, 1944, Laure went to Lyon. Was she weary of being shut up at home in Villeurbanne, seeing nobody? Did she simply want news of her relatives? Did she feel safe going to visit her friend Madeleine?

At fifty years’ removal it is easy to see how blind we were. We ignored the alarms that went off right up to the last minute. We knew we were going to be arrested but without really believing it. Like the family of dying persons knows they are going to die but can’t actually admit it. The horror is incomprehensible. And the blow fell.[13]

Madeleine Goldberg[14] lived at n° 64 cours Gambetta in Lyon. That is where the two women were arrested by the Gestapo. They were interned in Lyon’s Montluc fort. Madeleine Goldberg was put in cell 13 n° 7818 [15] and was freed without any explanation by a police inspector[16] on July 14, 1944. Laure[17], on the other hand, was transferred from Montluc[18]to the Drancy camp on July 24, 1944. A week later, on July 31, 1944, she was deported to Auschwitz in convoy 77.

The journey lasted four days and four nights in a lead-sealed cattle car, with no air, no light, no water, no food, but with wailing children, weeping women and the screams of those gone mad. At last the train came to a stop. The doors were opened. Howls rang out: “Raus!Los! Los!”[19]

When Laure got down off the train she didn’t know where she was, she didn’t know what awaited her.

“You there, off to the right. You, off to the left.”

I found myself on the side where there weren’t many people, just a small group of women between the age of 15 and 45. On the other side there were handicapped women, those who were older, and all the children. That is how they culled the ones who looked robust enough for work and those who seemed weak.[20]

Laure was with the more fragile women. She died at Auschwitz on August 5, 1944, most likely gassed.

Without any news at first, her family heard she had been deported to Ravensbrück, but nothing further. No confirmation. Her husband, Élie Cohen, died in January, 1945[21], perhaps of sorrow. Now an orphan, their son Roger faced the pain, the impossibility of getting over his grief without a grave for his beloved mother who died in the horrifying conditions he was gradually to discover.

In 1948 Laure was declared “a deportee who never returned, and unknown in the various files of the Aliens Bureau”[22]; the regularization of her civil status was to be long and difficult. All the formal steps finally abutted in the deliverance to her son as legal successor of political deportee card n° 211331576 on December 6, 1965.

As the lovely song says:

“May the blood dry soon as it fades into history”

So may Auschwitz serve us as a lesson forever

And may the deportees live on in our memories.[23]

Caption for the photo of the plaque[24]

National Center for the Resistance and the Deportation: Reminder of the Anti-Semitic Persecutions

[1] Marie Rameau, Souvenirs, Éditions la ville brûle, 2015, p.61.

[2] For the family names, see: Paul Sebag, Les noms des juifs de Tunisie. Origines et significations, L’Harmattan, 2002 : Taieb, Tayeb p.138 ; Ossona, Mendès-Ossona p.114-115 ; Cohen p.58.

[3] Marriage license n°10525. Information supplied by Moché Uzan, a rabbi in Tunis.

[4] I wish to thank Corinne Rachel Kalifa Sabban, who furnished me the birth certificate.

[5] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, Collection Témoignages de la Shoah, Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, Editions Le Manuscrit, 2006, p.61.

[6] Élie Boccara was the brother of Abraham Albert Boucara. See at: http://www.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/abraham-boucara/

[7] AD 69, Villeurbanne’s 1936 census: http://archives.rhone.fr/ark:/28729/a0113034782054iS8LZ/1/1

[8] AD 69, Villeurbanne’s 1936 census:

[9] Biography of Camille Joly : http://maitron-en-ligne.univ-paris1.fr/spip.php?article89586

[10] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.62.

[11] Yannick Ponnet, « Avec Paul Chabert, la Ville s’offre un buste du maréchal Pétain » : https://www.leprogres.fr/rhone/2015/08/06/avec-paul-chabert-la-ville-s-offre-un-buste-du-marechal-petain

[12] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.150.

[13] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.173.

[14] Madeleine Marcelle Goldberg, née in 1911 in Paris; she was married and had 3 children.

[15] Rhône Departmental Archives, Montluc 1942-1944, Record sheet N°003915. http://archives.rhone.fr/ark:/28729/a0113034779221mY1Wl/1/1

[16] She was given an attestation on September 22, 1944. Ibidem, Record sheet N°003915.

[17] Attestation established by Madeleine Goldberg on September 15, 1961 in Lyon. In : DAVCC Dossier déporté politique 21 P 250404.

[18] Rhône Departmental Archives, Montluc 1942-1944, Record sheet N°7182. http://archives.rhone.fr/#recherche_montluc:

[19] Recounted by Myriam Roubi, in : Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.238.

[20] Testimony of Ginette Kolinka, a survivor of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp: http://leplus.nouvelobs.com/contribution/1313086-a-19-ans-j-ai-ete-deportee-au-camp-d-auschwitz-je-n-en-ai-pas-parle-pendant-40-ans.html

[21] Death mentioned on his wife’s information sheet: http://archives.rhone.fr/#recherche_montluc

[22] Note dated November 23, 1948 addressed from the assistant director of the Police Générale to the head of the 3rd bureau of the Police Générale. In : DAVCC Dossier déporté politique 21 P 250404.

[23] Nelly Aubry, Poème sur Auschwitz. https://fr.calameo.com/read/0000089188ecb7c4010d9

[24] Centre national de la résistance et de la déportation : rappel des persécutions antisémites :

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c6/Lyon-D%C3%A9portation.JPG

Français

Français Polski

Polski