Joseph FRANCO

Biographie of Joseph René Franco, his life on the line

Joseph Franco was born in 1888 in Tunis, but lived in Paris for most of his life. A refugee in Lyon during the Occupation, it was there that he was arrested in July 1944. He was then transferred to Drancy camp and from there was deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944.

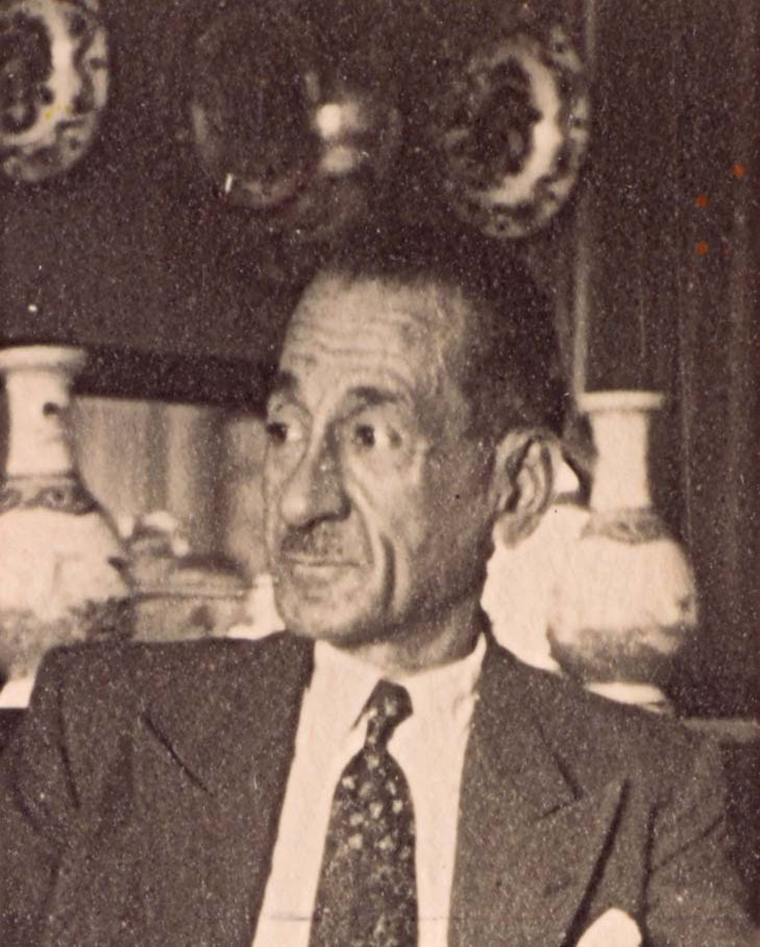

Portrait photo of Joseph Franco

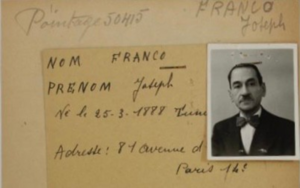

Photograph from the search file

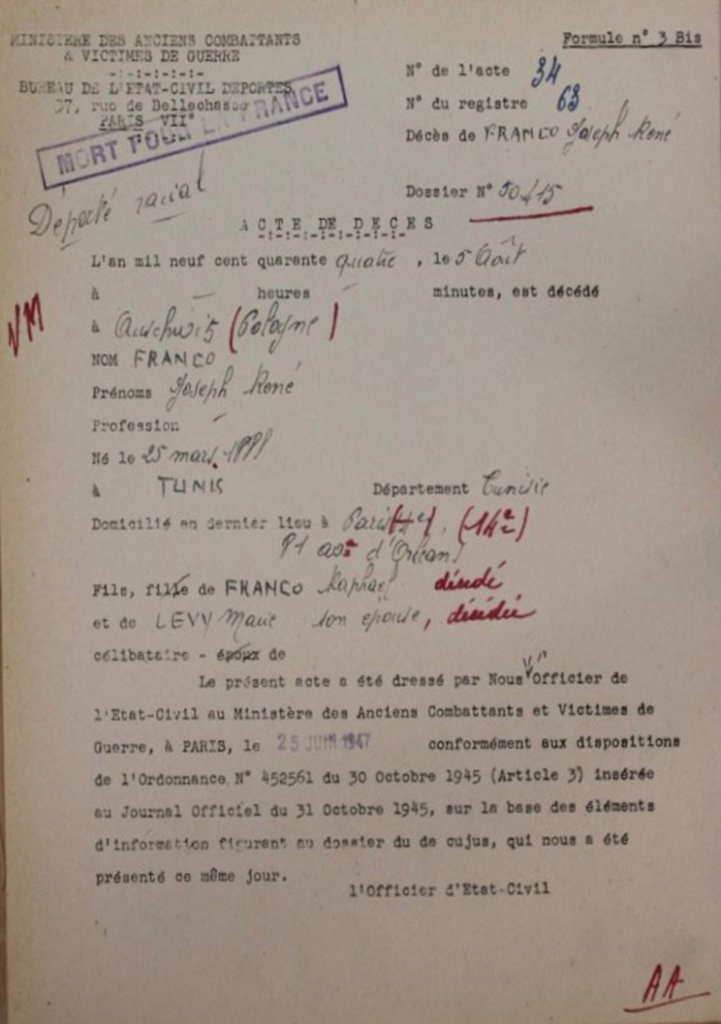

Joseph Franco was born on March 25, 1888 in Tunis, Tunisia. He was murdered on August 5, 1944 in Auschwitz, Poland.

His father’s name was Raphaël Franco, and his mother was Marie Lévy. We were unable to find any further information about them. Joseph was an only child.

Information about Joseph Franco

SHA 21 P 451 680

In 1922, Joseph left his hometown for France, where he settled in the 14th district of Paris at 81, avenue d’Orléans. He shared a flat with Charles Gilles, a painter, and his wife Jeanne Gilles. He had a very good relationship with them and considered them to be friends. He appears to have had a girlfriend called Jeanne Laroche.

The building at 81, avenue d’Orléans, (now called avenue du Général Leclerc) in 2021

Google Maps

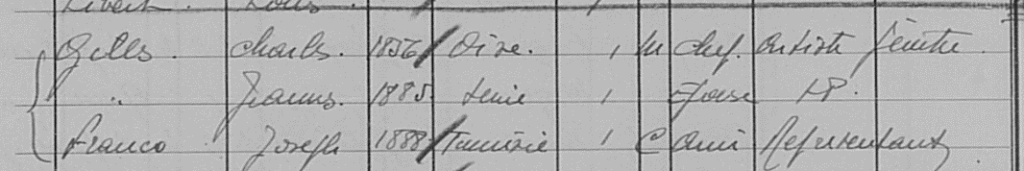

1936 census

Archives.paris.fr

To make a living in the capital, he worked as a salesman. In addition, based on a letter he wrote to his friend Eugene Estèbe, we can assume that he worked for the Finoki shoe store located at 87, Avenue au Maine, in the 14th district of Paris. The fact that he worked as a salesman helps to explain why he is always so smartly dressed in photographs.

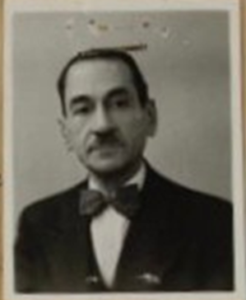

Identity photo of Joseph Franco

SHA 21 P 451 680

The Finoki company had several stores in the city and, according to reports at the time, they were well known in Paris and attracted a lot of customers. The success of this company was mainly due to the fact that they could afford to advertise. The advertisement below was drawn by the illustrator Germaine Bouret, a designer spotted by Walt Disney himself in the 1940s. He even said that she was the greatest illustrator of her time. This shows to what extent the store in which Joseph Franco worked was widely renowned.

Examples of advertising for Finoki stores

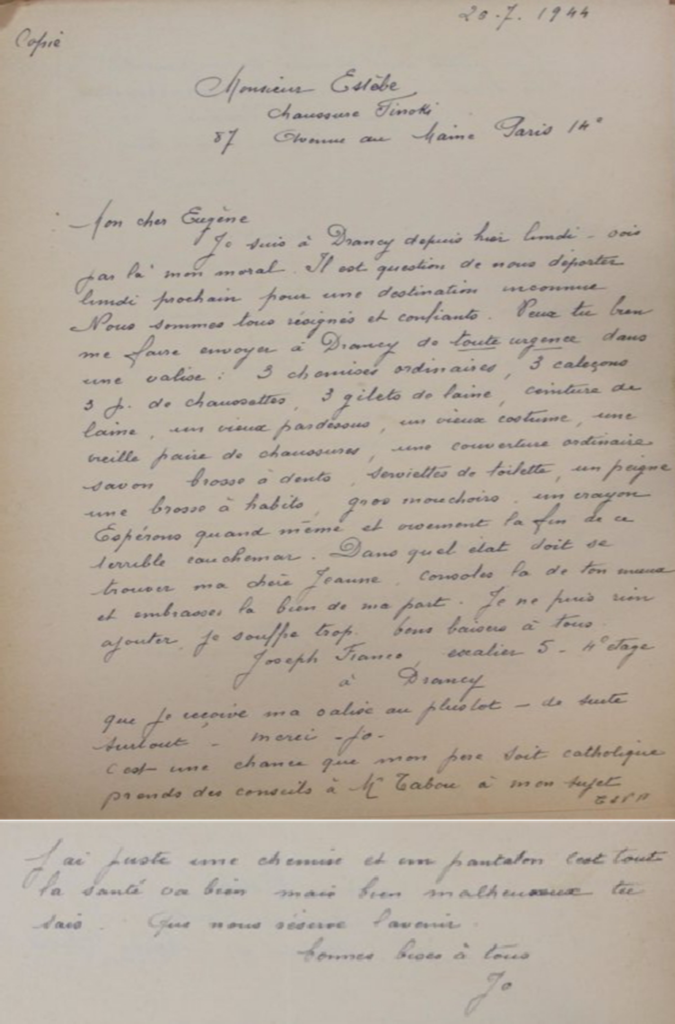

Lastly, the Finoki shoe store was also very important for Joseph Franco in terms of friendship. Indeed, it was here that he met his friend Eugène Estèbe, with whom he remained very close. This is apparent in the letter that Joseph wrote to him from Drancy.

Due to the anti-Semitic policy introduced by the collaborationist regime under Marshal Pétain, on September 3, 1941, Joseph Franco finally left Paris in order to seek refuge in the non-occupied zone. He chose to settle in Lyon. Once there, he found sanctuary at the home of a Madame Berle. She lived at number 6 rue Neuve, a few hundred yards from Place des Terreaux.

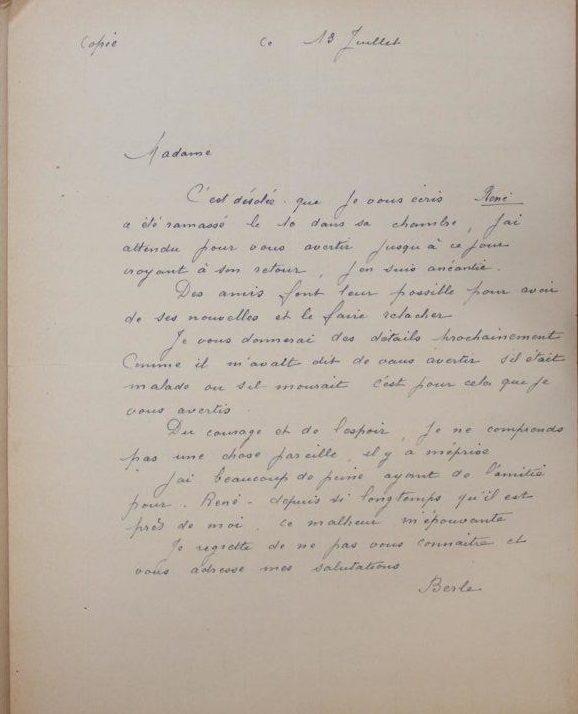

Finally, after living in hiding for three years at Madame Berle’s house, he was arrested there on July 10, 1944. Madame Berle later wrote to Joseph’s girlfriend, Jeanne Laroche.

This letter from Madame Berle to Jeanne Laroche is evidence of the kindness Joseph Franco showed to others. Indeed, Madame Berle and her friends were ready to risk their lives to obtain some information that might free him: “some friends are doing their best to find some news and have him released”. Also, it is clear that Jeanne and Joseph were very close, as demonstrated by the fact that she was the first person that Joseph wanted to inform of his arrest. Joseph must also have had a good relationship with Madame Berle, because she was committed to hiding him and was devastated when he was arrested.

Letter from Madame Berle to Jeanne Laroche, telling her that Joseph Franco had been arrested

SHA 21 P 451 680

And so began his journey to hell…

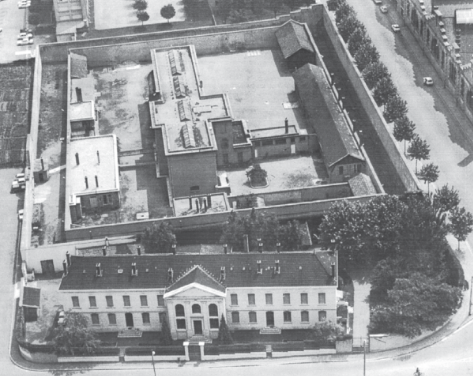

Joseph Franco was first detained in Montluc prison for nearly two weeks. This symbolic detention facility, which bears witness to the repression during the Second World War, opened its doors in 1921; it was a military prison until 1926, then a civilian prison until 1932, when it was closed. It takes its name from Fort Montluc, which lies across the street. In 1939, the prison reopened. First, from 1940 to 1943, it was managed by the Vichy regime authorities. It was then requisitioned by the Nazi occupiers until August 1944. During the German occupation, nearly 10,000 men, women and children were interned there. Among the prisoners were the children from the Izieu children’s home, and Jean Moulin, who was held in cell 130.

Montluc prison during the war

After a brief stay in Montluc, Joseph Franco was transferred by train to Drancy on July 24, 1944, as evidenced by the search sheet completed when he arrived.

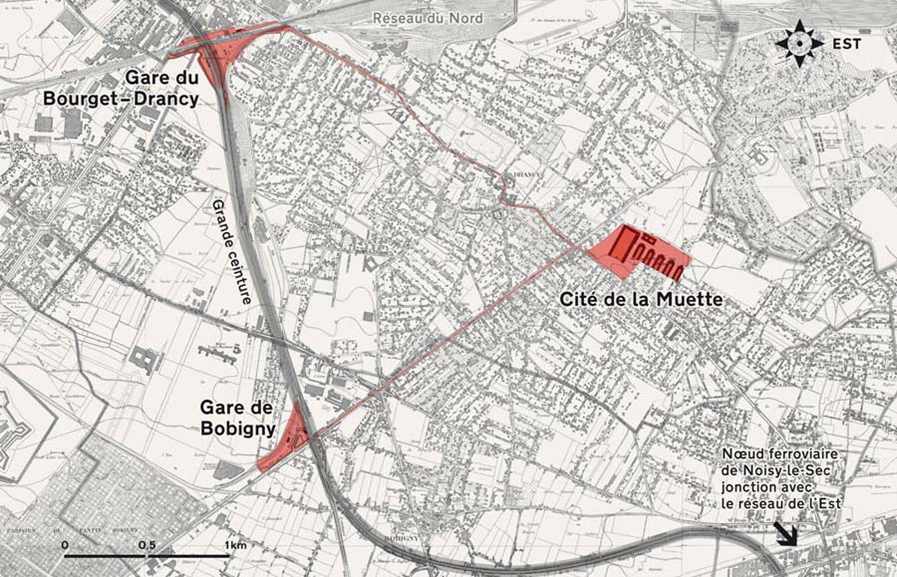

Drancy is located about 8 miles (12 km) northeast of Paris. It is a U-shaped group of buildings, made up of apartment blocks together with five tall towers (the last of which was never finished). It was one of the city’s first large-scale developments. The 15-story towers were demolished in the 1970s. Building began in 1932. It was intended to be low-income housing, but the project never got off the ground due to the financial crisis at the time. Besides, the apartment blocks in Drancy were not near any economically active areas. For example, there were no factories nearby, and therefore no potential tenants for the available apartments. The buildings were therefore quickly transformed into barracks for the military police. At the time, Drancy camp was called “la cité de la Muette” and it was considered to be ultra-modern. Its towers were the highest in France.

The locations of the Bobigny and Le Bourget railroad stations in relation to Drancy

www.garedeportation.bobigny.fr

People who had been rounded up arriving at Drancy camp in August 1941

www.ajpn.org

Drancy in the 1930s

www.pinterest.fr

Plan showing the location of Drancy

france3-regions.francetvinfo.fr

From August 20, 1941 onwards, the Cité de la Muette housed the 4,232 Jews rounded up in the eastern districts of Paris. The men interned were between 18 and 50 years old and were Polish, Romanian, Russian and also French.

Until the major round-ups in the summer of 1942, Drancy was a reservoir of hostages. The first convoy of deportees to Auschwitz left Le Bourget railroad station on March 27, 1942. 1,112 men, aged 18 to 60, were deported. Only about 20 of them made it back in 1945. In July 1943, a Nazi commander opted for another, more discreet railroad station, Bobigny. During its three-year existence, the Drancy camp was under the successive management of SS Theodor Dannecker (until July 1942), Heinz Röthke (until June 1943) and Alois Brunner from July 1943. Brunner received his orders directly from Adolf Eichmann.

The Vel d’Hiv roundup of July 16 and 17, 1942 marked the beginning of a second phase in the life of the camp. Women and children were now included among the internees. Between July 19 and November 11, 1942, 31 convoys left the camp, carrying 29,878 people. Others followed in 1943 and 1944, the last one leaving on August 17, 1944 from Bobigny railroad station. In total, 63 transports were organized. They took 65,000 people to the killing centers, mainly to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

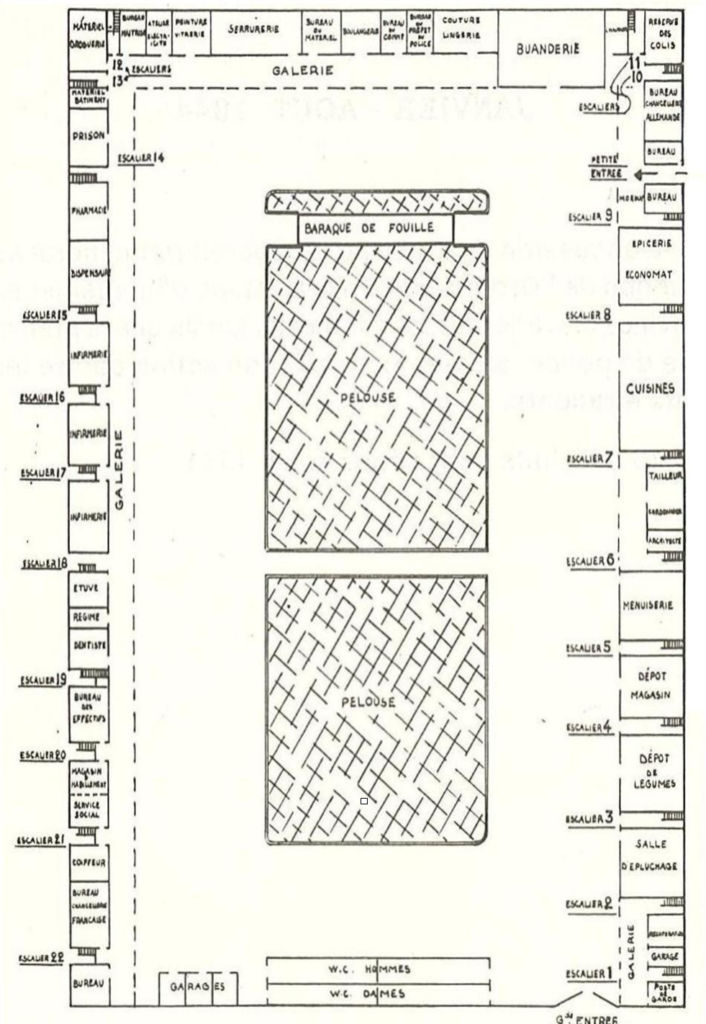

The first place every newcomer went to was the search room. It was the first stage of dehumanization, where all objects, identity cards and passports were confiscated. The internees were then registered: last name, first name, address, place where they came from, and why they were in Drancy (failure to wear the yellow star, being on the wrong side of the demarcation line etc.). Finally, they were given their room number.

The living conditions were appalling and highly regimented. The prisoners had almost nothing; some did not even have a bed or a blanket. They were kept in their rooms for most of the day, so doing nothing was their only option. The children, who arrived in August 1942, were separated from their parents. They did not even have a bed to sleep in and were forced to sleep on simple straw mats, or even on the floor. As soon as he arrived, Joseph Franco wrote a letter to Eugène Estèbe. We know from this letter where he stayed in Drancy camp: the 4th floor on staircase 5.

Plan of the ground floor of Drancy camp

Joseph Franco’s letter to Eugène Estèbe, written in Drancy

SHA 21 P 451 680

Joseph Franco wrote this letter the day after he arrived at Drancy.

In the letter, he tells his friend that he is to be deported “to an unknown destination” the following Monday. He therefore asks him to send him a suitcase containing clothes and toiletries as a matter of urgency. The cynicism of the Nazis, who led the deportees to believe that they were being deported to work in the East, is evident here. In the minds of the deportees, if they were asked to take a suitcase with personal belongings, it meant that they were going to live. He explains that he and his fellow prisoners are resigned to their fate, yet confident.

He talks about his feelings, saying that he is not in good spirits and writes: “Let’s hope anyway and look forward to the end of this terrible nightmare”. He is worried about his girlfriend, Jeanne Laroche, and asks his friend to console her as best he can.

He also touches on a very important subject. He mentions the fact that his father is a Catholic. There are several possibilities here. Either his father was really born Catholic, or he converted to Catholicism later in life, or he gave this information so that the camp authorities would take it into account and postpone his deportation. He would have been aware that letters were read before they were sent and this could have been a desperate attempt to escape deportation. In either case, this would mean that in theory he was not “deportable”, although there are many examples that show that in the frantic climate of arrests and deportations this criterion was not always adhered to.

He ends his letter by saying “my health is fine but I am very unhappy”. This is the last ever letter from a man who was devastated by his plight. He was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, and was probably murdered on arrival at the camp on account of his age.

Joseph Franco’s death certificate

SHA 21 P 451 680

As we are doing now, some other people have tried to research what happened to Joseph Franco during the Holocaust. One of them was Jeanne Laroche, who was his girlfriend, another was Mireille Boccara Cacoub, who was his second cousin, and another was Gilles André.

Here are several archived documents related to this research:

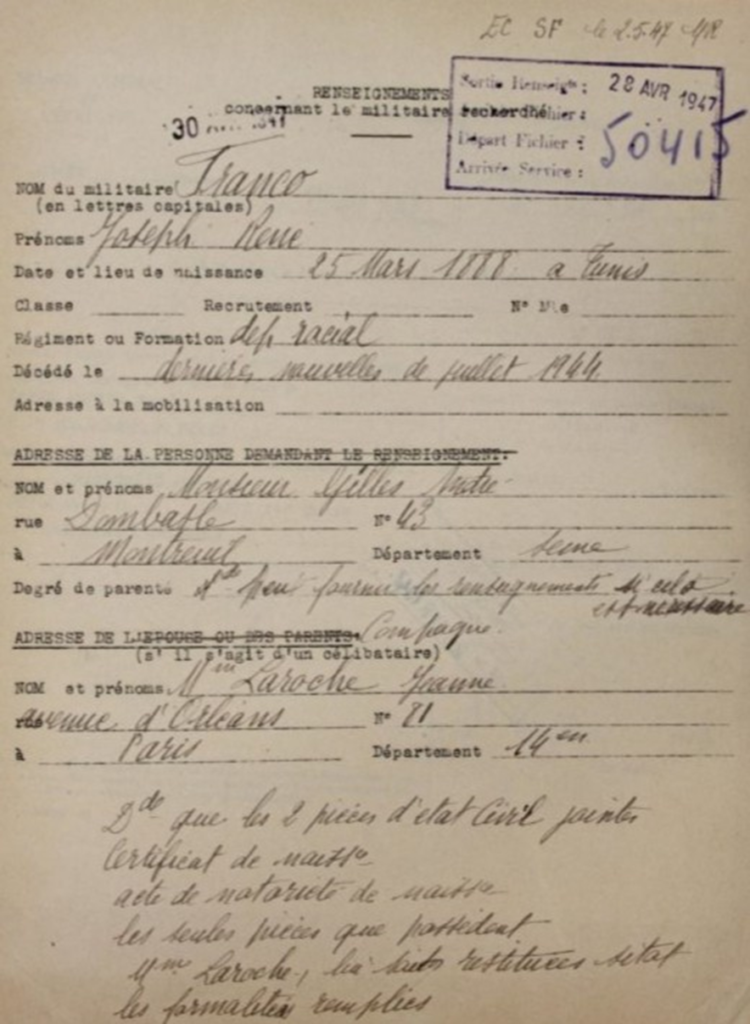

Information sheet, requested by Gilles André

SHA 21 P 451 680

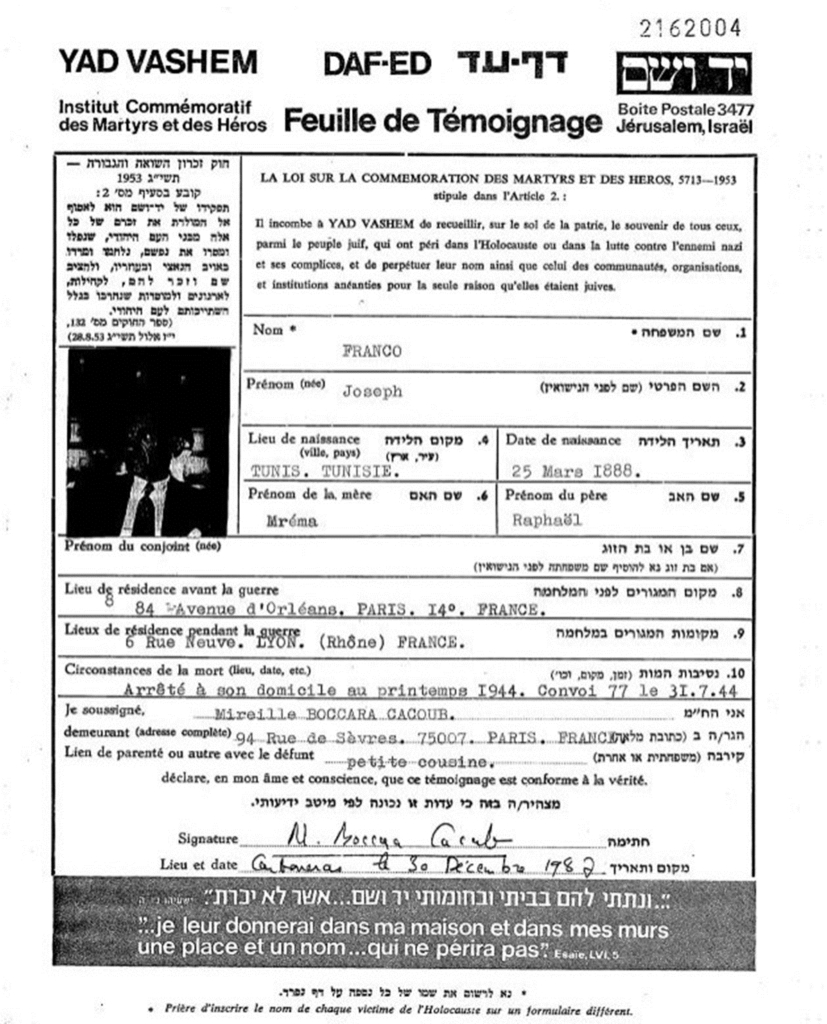

Testimonial sheet submitted by Mireille Boccara- Cacoub

https://www.yadvashem.org/

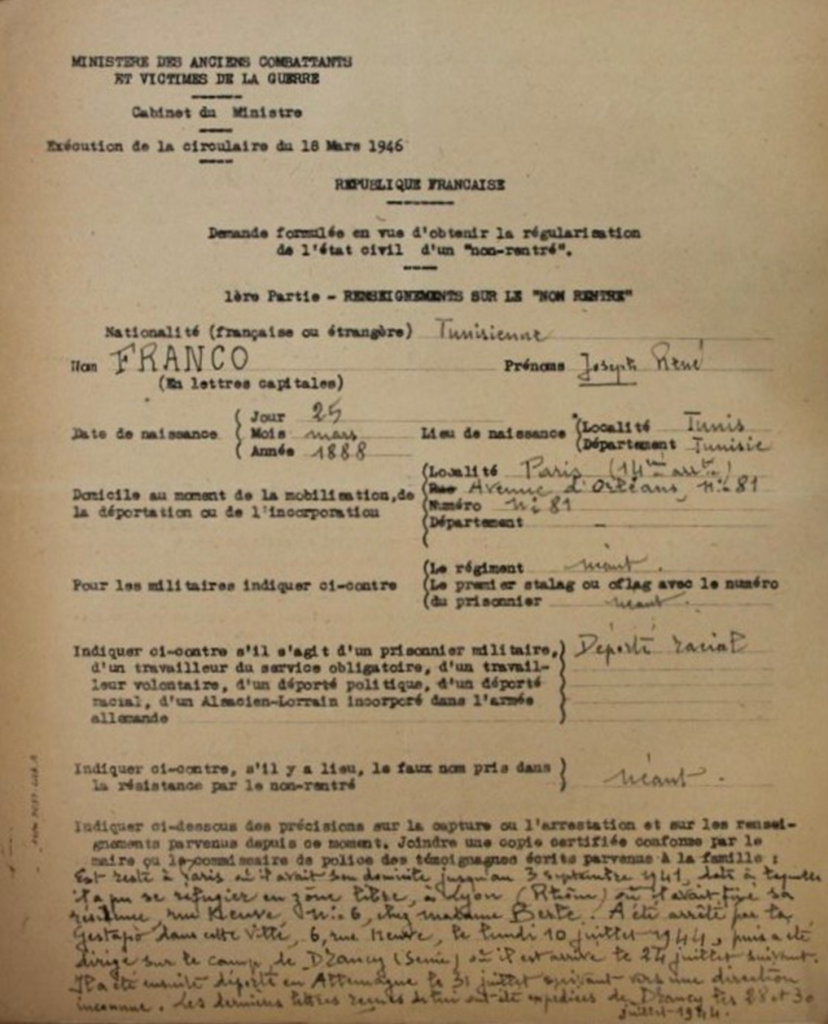

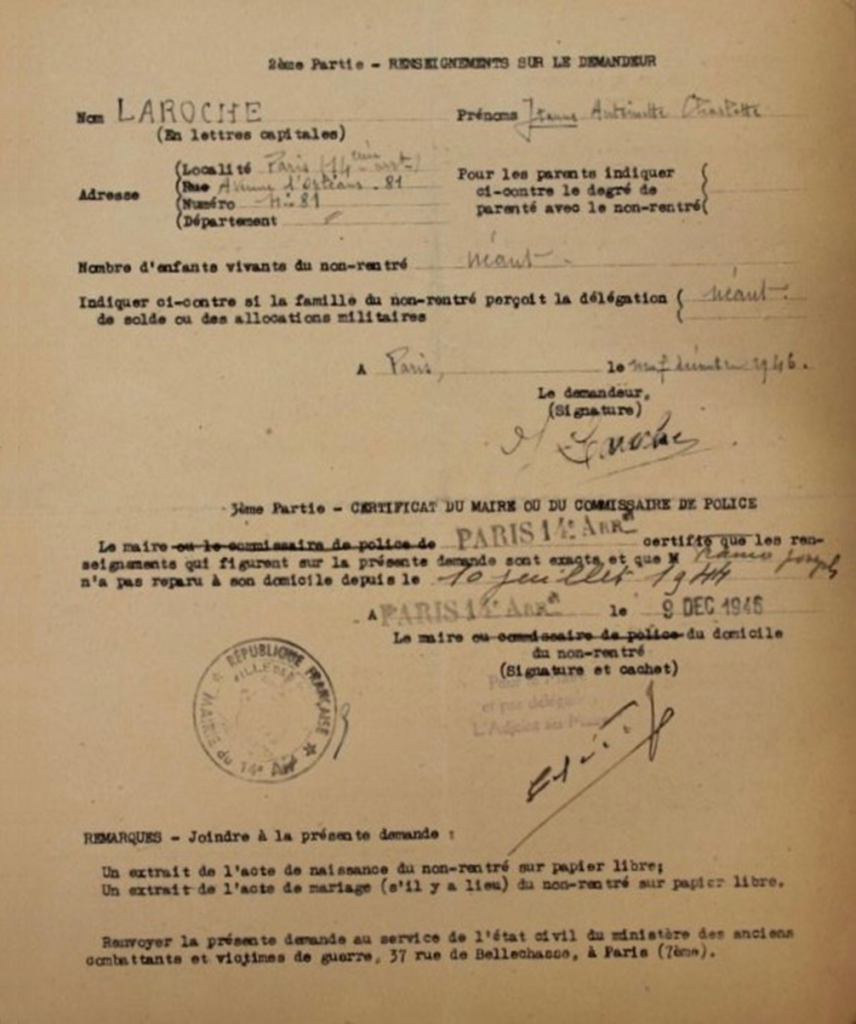

Information sheet requested by Jeanne Laroche

SHA 21 P 451 680

Sources

Defense Historical Service

- Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division (DAVCC), of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, dossier n° 21 P 451 680

The Shoah Memorial in Paris

- Drancy records, search book and transfer register

Contacts via social networks with a descendant of Mireille Boccara-Cacoub, his second cousin

Français

Français Polski

Polski