Frieda KOHN, née Fradel WAGNER 1894 – 1944

Portrait of Frieda and her husband

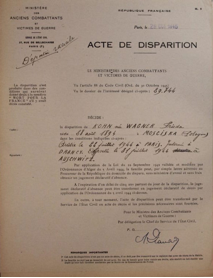

Frieda’s missing persons certificate

Frieda and Victor Kohn; a biography

Our group of junior high school students carried out an investigation into the lives of a deported couple, Victor and Frieda Kohn. Very little remains of them since their apartment was looted after their arrest: a few everyday objects, a handful of family photos, and some souvenirs passed on by their children to their grandchildren, including some cutlery and a small milk jug.

Cutlery – photo by Ms. Darley

A milk jug – family archives

As a way of bringing them back to life, we came up with the idea of giving a voice to those who knew them, written as if we had all really met them.

FRIEDA

Part 1: a meeting in London with Adèle, Frieda’s sister

Back to the past: we took the night ferry from Paris to London at 10 pm, from the Gare du Nord. We arrived in London the following day, at 9.10 am, at Victoria station.

On board the train, we began to review the various findings we had made so far. We were keen to get there and meet Frieda’s sister in order to complete our research.

We arrived around 9.10 am and went to meet Adèle. We sat down in a café under the glass roof of the Victoria Station and Adèle soon told us what she remembered about when she and Frieda were children:

“Our parents’ names were Judas Hersoh Wagner and Malka Rele Wagner. Frieda was born on August 28, 1894, under the name of Fradel Wagner, in Mosciska in Galicia. We were a very large family: 15 brothers and sisters, can you imagine? The eldest was Chaje Gitel, her Jewish name. She was born in 1885, a year before me… I was the second, and after me came Ruchel, born in 1888. Then came Hene Leie, Biene, and the first boy in the family, Abraham Bencyon. He was born in 1892, six years after me. Shortly thereafter Frieda was born, and our parents officially named her Fradel. In 1896, Perl Ettel was born, ten years after me. Then came Sura in 1900, then Majla, Glückel, and Wolf Ber, the second boy of the family, in 1905. A third boy was born two years later, Chaim Jechieskiel, and a last girl was born in 1908, Drezla. Oh, and I almost forgot Jacob! He was very close to Frieda, yet… I don’t even remember when he was born…

Civil birth register of Mosciska – Ukraine

A copy of the birth register of Mosciska, now in Ukraine but then in Austria-Hungary (see map). Between the two wars, this small town was in Poland.

A map showing the town of Mosciska, then in Austria-Hungary

By the way, there is something that may seem surprising to you: our first names varied between “official” names and regular names, on the one hand we had traditional Jewish names and on the other, more modern names. For example, my official name is Eidel Ryfke, although everyone called me Adèle!

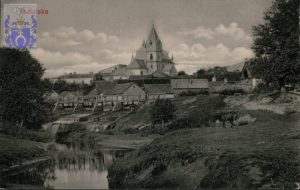

Old postcard

The main square in Mosciska – old postcard

Storefronts in Mosciska – old postcard

We were therefore a family of fifteen children, a modest family: our grandfather Abraham Benzione Wagner (or Bencyone, who knows?) was a carpenter and our father was a retailer, that is to say, he had a small business, he sold a little bit of everything in one of the small stores in the market place.

Mosciska on a map of Galicia, 1868

We lived in a small town away from the main roads, on a hill, a stream running through the landscape, a large mail square and small houses with their own gardens.

Unfortunately, our mother died at the age of 35, maybe in childbirth, I don’t really remember. Besides which, we don’t have any family photos from before the First World War. As I told you before, we were a lot of us, and we weren’t very well off: we couldn’t afford to have our picture taken.

Anyhow, after our mother died, the older girls had to take care of the younger ones. Gitel, Ruchel and I took care of our brothers and sisters as best we could. As they grew up, it was their turn to take care of the younger ones. Frieda, although six years younger, helped us very early on. She had a sweet nature and she took good care of the children.

In 1914, our family fled the pogroms that followed the arrival of Russian troops in Galicia. In fact, when the Russian troops arrived, a flood of Russian Jews poured in too, and our father became afraid. I think he thought that the anti-Semitic practices that were common on the other side of the border would arrive along with the Russians, and he decided it was time for us to leave. Also, during this period, the number of businesses run by Christians in small towns increased dramatically. These provided the peasants with all kinds of food at very reasonable prices while at the same time excluding the Jewish tradesmen. All this made our family finances even more problematic than they already were, and forced us to leave.

Displaced people from Galicia – Georges Muse for the Daily Mirror – 1915

Some refugees fled Galicia sitting on their belongings on carts, as photographed by Georges Muse for the Daily Mirror in 1915.

We took refuge in Vienna. Then, at the age of 20 or maybe 25, Frieda was entrusted to a benefactor who ran some restaurants. She was sent to Antwerp to work as a waitress in one of these restaurants. I too was sent abroad. I left for London right after Frieda, and I started working right away, just like her. In the end, we learned many languages in our lives… We spoke Yiddish and Polish in Mosciska. Then, when the Russians invaded us, we learned to speak Russian. When we fled, we had to learn German to communicate in Vienna: not to mention the fact that afterwards, we all went to live in different countries… Ah, we sure learned a lot of different languages in our lives…

I think I’ve told you everything I know about Frieda. And when I think about it, I think it would be wise to find this benefactor, because surely he could tell you more about Frieda’s life at that time.”

We thanked Adèle for having taken the time to tell us about her memories of Frieda and we said our good-byes to her.

By Oriane, Élise and Lola

Part 2: in Paris with Léon Ringer

Thanks to their marriage declaration, we discovered an important figure in Victor and Frieda Kohn’s life: Léon Ringer. He lived at 10, rue Buffault, in Paris, just across from where Frieda, Victor’s future wife, lived before her marriage, on rue Lamartine. Here is his account:

“There was a family I knew well, the Wagner family. At the beginning of the Great War, I learned that they had fled to Vienna. I visited them there and offered one of the older girls, Frieda, the opportunity to come and work in one of the restaurants I had in Western Europe, in Antwerp.

She knew how to cook kosher dishes perfectly, probably because after her mother died, she had to take on the difficult task of feeding her siblings. She worked in the restaurant for perhaps six years. She then met a young Hungarian, Victor Kohn, and it was love at first sight.

She then moved to Paris, France, where she married Victor. I offered her a job in my kosher deli on rue Buffault.

She is in this picture, right in the middle of the group, with a black dress under her white apron.

I was honored to be a witness at their wedding.

Frieda in front of the deli, “La Cachère” – family archives

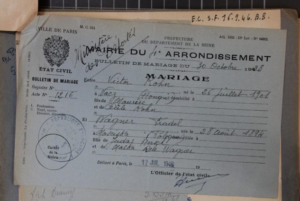

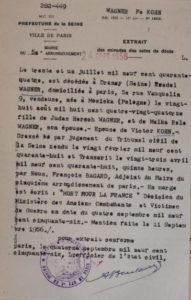

Marriage register – Paris archives – 4th district Town Hall – 30/10/1923

Unfortunately, I never met her again once she was married; she disappeared from my life. I remember that they left the hotel on rue Vieille-du-Temple where first lived and stayed for a while at 75, rue Doudeauville, in a very small apartment, with just a kitchen and a living room and a sleeping area in an alcove, but very warm and cozy.

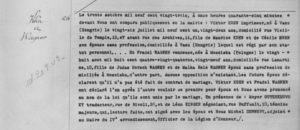

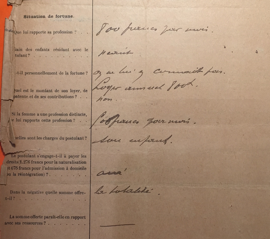

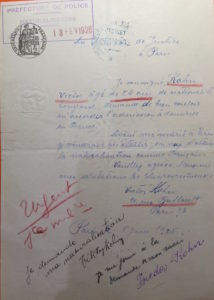

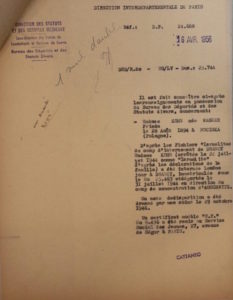

An extract from the naturalization file – record BB/11/9644

The rent for this apartment in 1922 was 800 French francs per year, the equivalent of one month’ salary for Victor. As for Frieda, she earned 500 francs a month. I suggest that you go to look at 60, rue Claude-Bernard, where Frieda went to work afterwards. It was a Jewish school where they provided staff housing for the cook.”

By Daniel and Léonard

Part 3: a statement from Victor’s best friend

In Antwerp, we met Armand, who had been Victor’s best friend since his teenage years.

“Hello, I’m Armand, Victor’s friend, and I will tell you what I know about his life.

Victor and I met in Czechoslovakia around 1920. We both came from Hungary, and we worked in the printing trade. We stayed there for maybe a year, before joining the merchant navy as apprentice seamen.

Where did we set sail from? Oh, I can’t remember… I’m getting old you know…

Anyhow, I can guarantee you that we travelled to the four corners of the world, from China to Europe, through Malaysia and India. One could say that we knew the world like the back of our hand. We stayed on one ship for almost a year and it was then, during a stopover in Antwerp, Belgium, that Victor wanted to stop in a small café to take a break. He had chosen a specific kosher place that reminded him of his family’s home and his mother’s cooking. You know how it is, nostalgia… Now, this café was the one where Frieda, his future wife, worked, although he didn’t know her yet. When we left, he asked me if I had noticed the waitress, because he thought she was the love of his life.

After that day, Victor and Frieda began dating. Frieda was also Jewish, but much more religious than Victor. She was born in a small town in Galicia, called Mosciska, if I remember correctly. It was in Poland by then. Victor loved her cooking, which was quite delicious (and he loved her too, of course). After a while, Victor came to see me and told me that he wanted to resign from the merchant navy and go to Paris to marry Frieda. She had managed to get a new job in a Parisian place, still with the same boss – this boss was a friend too, a benefactor even, I would say.

Victor and I therefore both left the Navy, and the three of us set off for Paris.

For a while, life was pretty quiet.

Frieda and Victor Kohn – family archives

Marriage notice – record 111922-KOHN_Victor_21P_581_244_111922_DAVCC_copyright

Victor and Frieda were married on October 30, 1923, at the town hall in the 4th district of Paris. Léon Ringer, their benefactor, and Meyer Outzerovsky, a translator friend who had helped them when they arrived in France, were their witnesses. A copy of their marriage certificate is in Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs’ file, since it was needed to issue the certificate to confirm that had died as deportees.

Frieda Kohn and her son Albert in 1924 – family archives

Frieda Kohn, her son Albert and her daughter Charlotte in 1931 – family archives

Frieda and Victor had two children, Albert who was born on October 16, 1924, and Charlotte born in 1931. You see, I can still remember their birthdays…

We also applied together to be naturalized as French citizens. I remember the scene well: Victor came home from work on June 1, 1925, and joined his family in their small apartment on rue Doudeauville. They told each other about their day’s work and then Victor brought up the subject of naturalization. Frieda did not understand why they should do this, so her husband explained that during the war there had been many casualties, and that he had read in a newspaper that the French government wanted to encourage people to be naturalized as French. Victor insisted that he had read in the newspaper “Le Matin” that the government was beginning to consider it, and he also said that to become French would be an honor, that it would mean that they could live in the most beautiful country in the world. In the end, Frieda gave in, but reminded Victor that she did not yet know how to write French very well. He reassured her and explained that we could write her request in pencil first and then she could write over it herself.

The three of us therefore, finally applied for naturalization in June 1925 and were granted it two years later, on November 30, 1927. We were absolutely delighted: it was like starting a new life. This naturalization was going to change our whole existence.

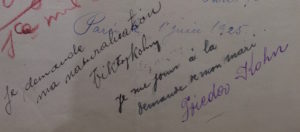

A handwritten letter in the naturalization file – record BB/11/9644

Frieda’s signature on the letter in the naturalization file – record BB/11/9644

On the naturalization application, we can see that the sentence written and signed by Frieda, “I join my husband in his request”, has been written in pencil and gone over in ink and also that the handwriting is not the same as Frieda’s firm and rounded signature. It is easy to imagine the involvement of an official from the Prefecture when faced with a woman who did not write French so well.

OK, I’ll skip ahead a bit in my story, Armand tells us, and we now find ourselves in 1939. When war was declared, Victor and I were posted to Alsace, initially in the 224th regional regiment of the 2nd battalion of the 8th company. Then in 1940, we were moved to the 7th colonial infantry regiment of the 9th company, and we stayed there for the duration of the “Phoney War”. Our regiment was first based in the Vosges region, to support the troops on the Maginot Line, then it was sent to Chantilly.

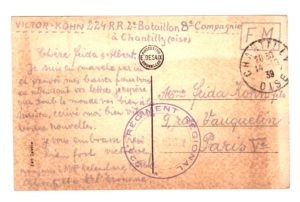

Postcard from Victor Kohn to Frida – October 14, 1939 – family archives

The front of the postcard of Chantilly from Victor to Frida – October 14, 1939 – family archives

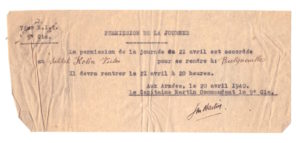

Victor Kohn, permission – April 21, 1940 – family archives

Finally, we retreated to the Ariege department of France, near the Spanish border, because the German army was advancing rapidly.

During this period of the “phoney war”, the school children, including little Charlotte, were evacuated from Paris for six months by the City Hall of the 5th district. They were sent to Ver-sur-Mer in Normandy.

The Jewish Consistory, on the other hand, had evacuated Frieda and Albert to Vichy. This was a huge problem for Victor because he wanted to stay in touch with his family. To do so, he sent letters regularly to Paris. After the evacuation, however, he did not know where his wife and children had been evacuated to. He therefore wrote them letters, but did not know where to send them.

I had already noticed that Victor could sometimes predict the future, but never about such a significant event.

He knew that his family was in danger, because he felt sure that the Germans would arrive soon. He wanted to protect them. However, he certainly didn’t expect the French government to collaborate with the Germans and he couldn’t have foreseen the atrocity of the events that were about to take place. Nevertheless, he wrote to Frieda to ask her to join him and the children in the Ariège where, by some fluke of wartime, he had finally ended up.

German soldiers on the Champs Elysées, in Paris

They tried to leave Paris, on June 13, 1940, but unfortunately, they were unable to escape from the capital due to unforeseen developments: the next day, June 14, 1940, you may not know this, but that was the day the Germans arrived in Paris. So, the day before, everyone in Paris tried to get out of the city as quickly as possible and go to the countryside: this was known as the Exodus. Frieda and her children, however, were not successful. Trains were the best means of transportation (in particular if you did not have a car) but the queues at the station entrances and even in the streets of Paris were incredibly long. It was impossible to cross the Avenue des Gobelins due to the crowd. The nearest station was the Gare d’Austerlitz. But after hours of waiting, when at last they managed to get onto the platform, there were no more trains. This meant that they were unable to get out of the city and it was up to Victor to join them in Paris a month later. That’s when we lost touch with each other, as I managed to hide in the free zone.

By Maïa and Apolline

FAMILY LIFE

Part 4: the story of the Kohn children, Albert and Charlotte, as told by their granddaughter

We met Victor and Frieda’s granddaughter, who came to speak at our school. She told us what her mother, Charlotte, who was 90 years old last January, and her uncle Albert, who died a few years ago, had told her. We spoke at length about their family life and here, through her voice, is the story of Victor and Frieda’s children.

Victor, Frieda and Albert Kohn with Jacob Wagner – family archives

Jacob Wagner, Frieda’s brother, was visiting his sister. This was in France, around 1926. Frieda decided to capture the moments spent with her brother during his visit by having a photo taken with him.

The photo, in black and white, shows Jacob Wagner, Frieda’s brother, standing at the top left; Frieda Kohn, seated, on the left; Victor Kohn, seated on the right; and their child, Albert, standing on his parents’ lap. The little boy does not look very confident on his feet, so his parents appear to be holding him from behind while he leans on a stick.

Behind this little family group, we can see curtains with flowery patterns. Were they at home, or in a photographer’s studio?

All are well dressed: the two men are in suits, wearing ties and pocket handkerchiefs, while Frieda is dressed in a long black dress. Albert, in the center, is wearing boots, shorts and a woolen sweater.

We can see a little family resemblance between Jacob and Frieda, who have the same shape of lips, nose and eyebrows. Also, it appears that Jacob was very close to Frieda…

By Elise

Frieda and Victor were loving and very affectionate parents. Frieda, our mother, worked for a long time as a cook, and before that she was a saleswoman in a butcher’s shop owned by Léon Ringer. Victor, our father, was a printer (I remember that he worked on rue Henri Chevreau in the 20th district of Paris). Well, actually he did not start out as a printer when he first arrived in France, he had to stop this work temporarily to take a job as a clerk while he perfected his French. This job earned him 800 francs a month.

To us, Victor seemed very modern and forward-thinking. He was very well-educated; he used to read books to us, Alexandre Dumas for example. Also, Victor taught his son to play chess. He taught us history and astronomy, which he was passionate about. According to Albert, his son, he greatly admired Einstein (and to tell you the truth, it was thanks to this education that Albert went to the Lycée Louis le Grand high school and Charlotte went to the Collège Paul Bert junior high school). He spoke four languages (Hungarian, Yiddish, German and French) while Frieda, our mother, spoke six (Yiddish, Polish, Russian, German, Flemish and French). Between themselves, they spoke German to begin with, and then French. When they didn’t want us to understand them, they spoke German (but we, the children, understood anyway).

She was very religious, while he was less so. This was her undoing: she thought that her faith would save her, that God would help her.

The whole family often went for walks to the nearby Jardin des Plantes or the Luxembourg Gardens. On weekends, we would go to the country near Saint-Ouen l’Aumône, not far from Pontoise – yes, at that time, it was still countryside around there.

.

The Châtelet theatre – old postcard

The Odeon theatre – old postcard

We also listened to a lot of music, because we had a gramophone, on which we often played Mistinguett’s records, and opera in particular: we all sang “Carmen” together. Our family often went out, we went to the Châtelet or the Odeon theater, and also to the cinema: we loved Laurel and Hardy, Chaplin, Jean Gabin and the first Walt Disney movies.

During the debacle of the “Phoney war”, while he was in the army in the 7th colonial infantry regiment, Victor found himself in Ariège.

Victor Kohn in the army – 1939 – family archives

At that point, Victor had a premonition of the “end”, so he asked Frieda to leave Paris, but since she refused, when he returned, he asked her to at least hide Charlotte (their youngest child) and it was he who showed Albert a way by which he could escape from the children’s home on rue Vauquelin, in case of a roundup.

By Nybras, Nina and Adèle

THE OCCUPATION

Part 5 : the testimonial of Mr. Marcel, the “errand-runner” at the UGIF children’s home

In the course of our research, we found that Frieda had worked at the Jewish school, at 60, rue Claude Bernard, but that she had then been hired by the Rabbinical Institute to work at 9, rue Vauquelin, which was the Maïmonide boys’ school boarding house..

9, rue Vauquelin today – photo found on the Internet

During the occupation, the Rabbinical Institute was forced to close down and the building then became a boarding house for young girls. A certain Mr. Marcel worked there at the time and left an impression on the memories of the survivors of that period, such as Yvette Lévy.

We therefore asked Monsieur Marcel about the history of the orphanage for young Jewish girls at 9, rue Vauquelin during the Second World War. He began by telling us this:

“27 orphan girls were housed there, hidden by the UGIF [Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews]. From January 1944, these homes had been run by a Mrs. Mortier. There were also instructors who were in charge of the activities and then the scouts who came there a few afternoons a week (I think you know one of them, who was called Gypsie)”

He continued his story by explaining his role in the home:

“In the morning, I would go shopping for Mrs. Kohn, who was originally the cook and then became the warden of the orphanage. Well, there wasn’t much left to cook! I used to leave early in the morning for the nearby market, the Patriarchs’ market, because from 1942 onwards, the cook being Jewish, she could no longer do the shopping because of the curfew and the restrictions. However, as I was not Jewish, I could go out whenever I wanted. At midday, I would drop off the groceries and then take messages from the girls to their parents: they were not actually all orphans, in fact. Some families had placed the children there to board in the hope of hiding them and saving them from danger. After the meal, I would go to deliver the letters to their recipients and then go to see the mother of one of the girls. She was disabled and lived on the top floor of her building, so I used to help her out.

It was not until July 22, 1944, that this routine was shaken by the very event we had all been dreading. When I entered the orphanage that morning and opened the door, instead of hearing the usual hubbub of lively girls, I heard a deadly silence. The groceries slipped out of my hands; potatoes strewn on the floor. The neighbors, seeing the door open, ran over and told me about the nightmare of the previous night. The SS had arrived at 5 o’clock in the morning. They had taken them all away, all of them.”

Marcel confided to us that he remained in shock for the next few days. He could not accept the reality of the situation and he still had hopes of seeing them again:

“And two days later, Mrs. Mortier appeared in the doorway as I was cleaning the floor. It was as if I’d seen a ghost. For a few minutes we remained frozen, facing each other, with big tears running down our cheeks, until finally she whispered these few words: “Marcel, the errand-runner”, that was what they called me at the home. Mrs. Mortier had come to get clothes for the girls because in the rush they had been taken to Drancy in their nightgowns. After that, I never saw her again.”

By Nour and Violette

THE END

Part 6: Yvette Lévy, a Convoy 77 survivor, tells her story

We finally found one of the girls who was at the children’s home while Frieda was working there, Yvette Lévy, who was nicknamed Gypsie. She told us the following:

My name is Yvette Lévy, and my maiden name is Dreyfus. I was born in 1926. I was a volunteer at the UGIF, the Union of French Jews, at the home on rue Vauquelin, and I stayed there some nights. It was there that I met Frieda, Mrs. Kohn. At that time, in the summer of 1944, she was the concierge.

The arrest took place on the night of July 21-22, 1944. It was led by the head of the Drancy camp, Alois Brunner. From Drancy, we were deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, on Convoy 77, the last convoy to deport Jews from Drancy to Auschwitz. I worked in the camp, and that’s how I survived.

So, if I’m to tell you the story in the right order… The arrest took place in the middle of the night, from July 21 to 22, 1944, one of the nights that I stayed overnight at the UGIF. Jewish resistance fighters often came to take refuge in the UGIF, which is why, when the SS arrived, Frieda was not suspicious when she opened the door. Well, why would this night have been any different?… It was then that the roundup began. I know that some children managed to escape through a passageway to a courtyard behind the buildings. We had planned to escape out of the window using a plank to get into the courtyard of the neighboring nunnery, but we did not have the time. My older brother, who was also there, was luckier: thanks to the intentional slowness of the janitor who was supposed to wake us up, that’s to say Victor, Frieda’s husband, he was able to escape with some friends and hide in the nearby covered market, the Patriarchs’ market. They were therefore able to avoid getting arrested. There was Frieda’s son and Victor as well, I believe, and the two daughters of the manager, Mrs. Mortier, who hid in the stairwell of a nearby building.

The SS took us away in a tarpaulin-covered truck and, flanked by the black German cars, we sang all the way to the Drancy camp. When we got there, it was during a heat wave. Well, it was the end of July, wasn’t it? And we were at no time allowed to have water when we arrived. The rooms where we stayed during the few days we were there were cramped and in a deplorable, disgusting state, and were infested with bedbugs.

Drancy record – 29F48C1

A document in the Ministry of Veterans Affairs’ archives shows that Victor was held in Drancy, from July 22 to 31, 1944, and then deported. After those few days, the call came and we were gone. On the convoy, the one that took us to Auschwitz, there were 1,306 people, including about 300 children under 16 and a newborn baby about ten days old, in a cardboard box that served as a crib. There was also an old man on a stretcher. I remember seeing Frieda in the convoy, but I have no memory of Victor. I must admit that I only knew him by sight; he was not at the home during the day because he was working elsewhere, whereas Frieda, whom I called Mrs. Cohen rather than Mrs. Kohn, yes, I used to see her every day.

We left for Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. The journey lasted three days and three nights in cattle cars with about 100 people in each wagon. There were two buckets, one for water, the other for “needs”: the door was only opened once to empty it. We were sweltering in the heat.

During the night of August 3, the train stopped at the very back of the camp, near Crematorium II. During the “selection” we were separated into two groups: there were those who were going to be taken to work in the camp, as I was, and the others who were sent immediately to the gas chambers. When we got off the train, I remember seeing Frieda with the director, I think, a white-haired lady, surrounded by young girls from the UGIF and they were all selected for the gas chamber. As for Victor, I don’t remember seeing him on the platform and so I don’t know if he was gassed immediately or not. But he was over forty years old, so…

By Lucie and Louison

Victor does not appear on the list of people who were admitted to Auschwitz, unlike Frieda, but we know that they probably died there on August 3, 1944 (rather than on July 31, 1944 in Drancy, as it is stated on their death certificate). They were gassed on arrival, without ever entering the camp.

“Died for France” – Frieda – 29CA9D1- DAVCC du SDH -1024×683

In 1956, at the request of their children, the couple were recognized as having ” Died for France”.

The authors:

Nybras Ayari, Adèle Bonnier, Oriane Cabrol, Augustin Curtet, Aurélien Deleplace-Sigot, Elliot Gregory, Apolline Joly, Léonard Lazzari, Violette Montagne, Nour Mghaith, Garance Peslin, Daniel Raichman, Nina Ramaget-Vornetti, Maïa Riva, Lucie Sanchez, Louison Varin, Élise Vergnes and Lola Wartel-Paoli wrote the texts.

The text and illustrations were edited by Aurélien Deleplace-Sigot and Ms. Darley, the group’s history and geography teacher.

Sources:

The file held by the DAVCC of the SHD of Caen (the Division of the Archives of the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts at the Defense Historical Service) for Victor and for Fradel (Frieda) Kohn; the civil register of Mosciska (now in Ukraine); the civil register of Vacz (Hungary); the exhibition catalog “245 years of printers in Vac, 1772 – 2017” (Nyomdaszati katalog www.muzeumvac.hu); the naturalization decree n°25263 X 26 dated November 30, 1927 (file number BB/11/9644 at the National Archives); the resources of the Shoah Memorial, the memories of Mrs. Charlotte Kohn passed on by her daughter, Mrs. Kaminsky (meeting with the group on January 14, 2021 and letters); a telephone interview with Mrs. Yvette Lévy (December 2020); the Kohn-Kaminsky family archives (photos, postcards, various documents); a few old post cards.

Français

Français Polski

Polski