Roland FLACSU

deported to Auschwitz, Häftling (prisoner) n° B3753.

Extract from his son Pierre-Gilles’s blog (in French only) — the page dealing with “My family stories > the Flacsus from Romania > Roland Flacsu deported to Auschwitz”. Our thanks for his permission to reprint. Direct consultation of his site will yield a profusion of interesting stories.

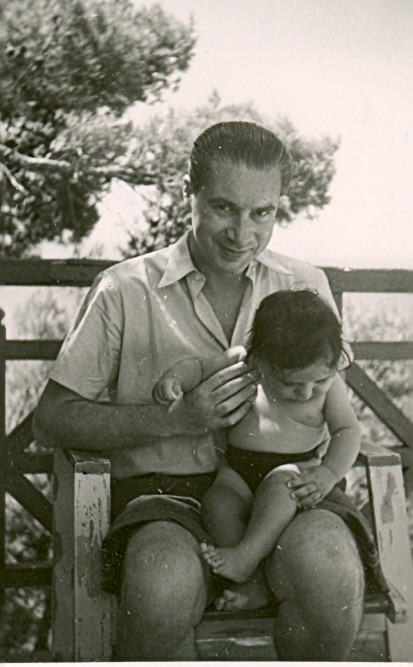

Roland Flacsu was my father.

When I was a child Auschwitz seemed to be omnipresent in our daily conversation. Mealtime was particularly prone to broaching the subject.

My father never, however, related his arrest or the ordeal that followed.

I have had to search the archives, investigate, collate the documents, seek out witnesses, just as if it concerned a stranger.

In 1939 he was mobilized; with the rank of sergeant he was his regiment’s (13th Light Infantry Brigade) radio operator, and was taken prisoner (with his whole regiment) at Châteaugiron (near Rennes) on June 18, 1940 in the debacle of the French Army.

These soldiers apparently fought many times against the irresistible advance of the German panzers from the Ardennes all the way to Brittany.

He managed to escape rather quickly from the “Frontstalag 132” where he was being held prisoner in Mayenne. He went home to Lyon and was formally demobilized on December 12, 1940.

Flacsu military record reconstituted in 1951

I seem to recall hearing that he and some buddies disguised themselves as Red Cross nurses to get out of the Stalag.

He went back to his family and to work in Lyon.

He lived at 27 rue de Créqui with his wife Rose and their daughter Arlette.

The Flacsus rented an apartment on the fifth floor of the recently built (1937) building at that address.

Rose’s parents, Jacques and Clotilde (née Alexandre) Jacob lived with them from September, 1939.

Jacques Jacob was blind.

Letter drop for a Resistance network

During the Occupation he was a “letter drop” for Madame Levesque (Henriette Masquelier) of the “Vic Alexandre” network (Buckmaster network, created and commanded by the British to engage in intelligence and escape operations…) from the start of 1943 to the start of 1944, when Henriette Masquelier was arrested. She was deported to Ravensbrück. Roland’s role was limited to receiving documents or packages from strangers and transmitting them to Henriette Masquelier.

Mme Masquelier-Levesque confirme (confesses ?) to the police …. (document BAVCC Caen)

He managed the “Raoul” store (a major retail chain at the time) at 52 rue de la République in downtown Lyon. It was an ideal spot for discrete contacts in the crowd of passers-by. Madame Masquelier’s residence was at 129 rue de Créqui, and Roland lived at n° 27 on the same street.

The arrest on June 20, 1944

Roland was arrested by the Gestapo on June 20, 1944 with his family (Arlette, Rose Jacob and her parents). He was imprisoned and tortured at Montluc (from the 20th to the 30th of June) and then transferred to Drancy, where he was held the whole month of July.

Official record of Roland’s 1950 account of the events (Archives BAVCC, Caen)

The Fort Montluc prison

At the Montluc prison Roland was no doubt held in the courtyard “shack” according to information given by Bruno Permezel (Association of the survivors of Montluc).

The Jews’ Shack in the courtyard of Montluc prison (photo courtesy of Jean Baruch)

I believe I heard Roland speak of torture at Montluc, and I have read that it was systematically applied. During this time Arlette was separated from her parents (cf. following page).

They were transferred to Drancy on July 1st.

Drancy, the holding camp guarded by the French

Data sheet n° 24755 / 6224 established on arrival at Drancy states that he came with 11,085 francs, a gold signet ring, and a tie pin.

“Receipt” established upon arrival at Drancy (Mémorial de la Shoah, Paris)

Roland, Rose, Arlette, Clotilde and Jacques Jacob spent the whole month of July at Drancy.

Deported to Auschwitz in convoy 77

From Drancy they were deported Auschwitz on July 31, 1944 (convoy 77). Arlette, her mother, Rose Jacob (who was pregnant), and Rose’s parents were not “selected” as laborers and were thus gassed August 4, 1944).

Data sheet from the Auschwitz archives

The will to eventually avenge Arlette’s death seems to be one of the essential sources of the energy he found to survive.

Official record of Roland’s testimony about Rose, Arlette, and M. and Mme Jacob (BAVCC, Caen)

Convoy 77 took 1300 deportees from Drancy; 726 of them were gassed on arrival; of the 574 people who were admitted to the camp, only 209 still survived in 1945.

The “selection” getting off the train at Auschwitz

Roland was selected, tattooed (B3753), and was to survive.

Several of his comrades at Auschwitz testified after the war: Doctor Isidore (or Isic) Fischer, who was with Roland at Montluc, then for a month at Drancy, and finally at Auschwitz until his transfer to the Stutthof camp in East Prussia (October, 1944), Claude Haguenauer (whom I remember my father going to see occasionally when I was very young), Gérard Klebinder, ….

Not long before the evacuation of the camp and the “death march” (January, 1945) he was wounded at work (his knee crushed by a trailer he was pulling).

This accident has been described by one of Roland’s fellow prisoners, Alex Mayer, who wrote an account of his deportation in the days immediately after the camp’s liberation. This account was published (Auschwitz, le 16 mars 1945, édition Le Manuscrit). On page 75 he writes: “The same vile character (a Polish Kapo) was responsible for an accident that killed one of us and almost killed one of my good comrades. We were required to maneuver a heavy car trailer. He failed to help us hold it back going down a slope, and Roland F. was caught under a wheel. He would pull through miraculously, but X’s abdomen was crushed and he died after two days of horrible suffering.”

Roland was taken to the infirmary of the camp and treated.

He was later to tell about the absurdity of an extermination camp where the wounded were treated (and apparently skillfully, as the doctors were also Jewish deportees). His “hospitalization” in the infirmary spared him the evacuation march that was fatal to the majority of the deportees who had to undertake it.

Klebinder, one of his deportee comrades, told me that his life was also saved by being hidden by Roland under his straw mattress in the infirmary.

Roland Flacsu (3) and Alex Mayer (14) figure on this list

Above is the list of 90 prisoners in the infirmary, established on January 18, 1845; Roland is n°3 (document ITS at Bad Arolsen n° 506695), Alex Mayer is n°14.

On January 27, 1945 they were liberated by the Red Army. There remained about 7000 deportees there, left behind as “unfit for the march”.

Below is a list of former Auschwitz prisoners established after the arrival of the Soviet troops (document ITS at Bad Arolsen n° 534700), on which the state of their health and their illnesses resulting from detention conditions are documented, with Roland’s diagnosis (4th on the page: “contusio et vulnero reg. genu utriusque”.

List established after liberation by the Russians

I do not know how long they remained at Auschwitz after the arrival of the Soviet troops. On the sheet from the camp’s archives that is shown above is found a date, May 2, 1945. I have no idea what it means.

During these weeks he and others were healed. Others, too weak to be restored, died. I recall my father saying that the Russians gave them caviar in big iron buckets; many starving deportees fell upon it. But this choice food was much too rich for their ravaged organisms to assimilate. He said that some buddies died of it. Even when his means had considerably improved and he came to enjoy refined foods, he would never eat caviar.

He was to spend weeks traveling through central Europe in a Soviet uniform, going from Auschwitz to Bucharest, then to Odessa, where he embarked on a British ship which, after a stopover in Alexandria, brought them back to Marseille.

In a fictionalized account, la Trêve, Primo Levi has related the wanderings of the Italian survivors like himself through the territories recently liberated by the Soviet armies.

There are some differences from what Roland must have experienced; the Soviets regrouped by nationality the people they found while liberating the lands from the Nazis.

The Italians, some of whom were deportees or war prisoners, others soldiers of Fascist Italy, were not treated the same as the French, who were considered “partisans”…

The return

He arrived in France on July 7, 1945.

He came via Paris; his cousin Pierrette recollects his arrival at the Magenta housing block. Back in Lyon in July, 1945 — a little more than a year after his arrest — he recuperated his job, his apartment on the rue de Créqui, and part of the furniture and possessions that had been filched. This was to furnish the subject matter for some rather epic tales.

The employees of the store had divided up his personal possessions. (He particularly mentioned a pen of which he was quite fond, which I later gave to Alexandra.)

His apartment on the rue de Créqui had been requisitioned and allotted to a bureaucrat of the Préfecture who refused to give it up. An article by a friend in the newspaper rapidly took care of that problem.

As for his furniture, a neighbor lady had followed the second-hand goods dealer on her bicycle and identified him when he took possession of them after the arrest. He told us how he went to this “merchant’s” warehouse, where the man proposed to sell him his own furniture and goods; he recovered all of it by threatening him with a revolver!

His political deportee card established in 1953 states on the back that he received 60,000 francs on July 30, 1953.

Some new elements…

Unfortunately, most of those who could have given me information are deceased.

I well remember Gérard Klebinder and his wife. He was an important witness at the trial of Klaus Barbie. While looking for Claude Haguenauer, I made the acquaintance of his daughter, Evelyne Haguenauer, who knows about the same things as I do about Auschwitz….

But the contingencies of research sometimes turn up some surprises.

There was a witness to the arrest of the Flacsus.

Witness to the arrest of the Flacsu family

Georges Boiron was present at the arrest (BAVCC, Caen)

Odette Alexandre filed a complaint:

On October 9, 1944 Odette Alexandre went to the les Brotteaux police station in Lyon. She was 18 years old. She was the daughter of Achille Alexandre and Alice Israël. They also lived on the rue de Créqui, at n° 41. Her father, Achille Alexandre, was the brother of Clotilde Alexandre and thus Rose’s uncle. Achille Alexandre was arrested and deported to Auschwitz in convoy 78 from Lyon on August 11, 1944, with his youngest son Claude, who was only 20 months old.

At the police station Odette Alexandre declared that her cousins had been arrested and deported to Germany at the end of the previous June, that on August 20th a neighbor, Madame Boiron, had witnessed the removal of the furniture, that she had followed the moving vans to the furniture dealer’s warehouse on her bicycle… She indicated that Madame Boiron had phoned the dealer to inform him that the furniture belonged to Israelites arrested by the German police and warned him how he should conduct himself.

Odette Alexandre then gave a quick description of the furniture.

The police investigate:

Following up on Odette Alexandre’s complaint, police chief Redt called in Monsieur Raymond Rançon, furniture dealer, for questioning. He claimed to have bought the furniture in question on August 21 from Mlle Yvonne Coindat, who told him that was her home and showed him I.D. card n° 2670. The price of 60,000 francs was fixed, to be paid in cash at the time of removal, as Mlle Coindat refused payment by check. Monsieur Rançon confirmed that three or four days later he had received a phone call from a lady who had remained anonymous and told him that the furniture belonged to Israelites arrested by the Germans.

He added that he had set aside all this furniture at once and made an inventory of it in the presence of Mlle Alexandre and Chief Inspector Jouvenel of his department….

On October 16, 1944 police inspector Gaston Darribau indicated in his report that at the end of June this Coindat, Yvonne Maria… moved to n° 27 rue de Créqui under the name of Leroyer. Without the least justification to the manager or the concierge she took over the 5th-floor flat of a Jewish family arrested a few days before by the German police. Several days later two men, a German who answered to the name Frank, and a Frenchman named Paul also came to live in the flat. They stayed until August 21, 1944, on which date Mlle Coindat had all the furniture belonging to the Flacsu family moved out before vanishing… Searches for Yvonne Coindat carried out in the Lyon conurbation proved fruitless.

Should it be of any use, a photograph of this person is attached, which the concierge and other neighbors formally recognized as the tenant of 27 rue de Créqui. This photo was found in the drawer of one of the pieces of furniture sold by Yvonne Coindat to Monsieur Rançon….

On October 14, 1944 police inspector Gaston Daribeau had questioned Monsieur Joseph Seveleder, the concierge of 27 rue de Créqui, who had specified that during June, 1944, after the arrest of the five members of the Jacsu/Jacob family, a woman calling herself Leroyer moved into the furnished apartment on the fifth floor of the building…. He stated that she let herself into the apartment without the manager’s authorization, as she had the keys….

The police pursued its work and Yvonne Coindat was arrested.

She was brought to trial in 1945-1946. An investigation file was compiled; testimony was collected.

The Lyon Law Court sentenced her on February 5, 1946 to 3 years in prison for treason…. after which she was apparently pardoned…

I have only had access to certain elements of this file; questions remain that cannot be answered from these elements:

Yvonne Maria Coindat moved into the apartment of my father and his family a few days after their arrest, which took place on June 20, 1944; she had the keys but had not obtained them from the manager or the concierge.

Is it known exactly when she moved in?

How did she get hold of the keys?

Was she or her friends a party to the arrest?

My father — who came back alone from Auschwitz — arrived in Lyon in July, 1945. After a few adventures he recuperated the flat, the furniture, the crockery…

Was he interviewed in the case undertaken against Yvonne Coindat, during the investigation and/or when the case was brought up before the Court?

Was Odette Alexandre, Rose Jacob-Flacsu’s first cousin whose complaint initiated the case, brought into the case anew?

The police operation leading to the arrest of my father and his family, and subsequently to the death of four people at Auschwitz (Arlette Flacsu, Rose Jacob, Jacques Jacob and Clotilde Alexandre), seems to have been motivated solely by a wish to nab the apartment (scarce at the time) at 27 rue de Créqui…In other testimony my father said that he had been reproached for anti-German propaganda, but declared: “I realized that the Gestapo was unaware of my activity against the occupation forces…” The investigation file might reveal what was what….

A few notes

At the start of this page I said that I remembered Auschwitz as a daily presence in my childhood.

There was, however, no history lesson or even any recollection of the suffering and the dead. Only tiny things that others might find banal, a bit obsessive…

For example, at meals my father distributed the food — bread, pâté, a pie. The shares were always rigorously equal. Innumerable times I heard the explanation: in the camp when there was a loaf of bread for six, eight or ten prisoners it was the rule for the who one who cut the shares to get the last piece; If he cut them unevenly, he would be sure to get the smallest part. Survival imposed strict exactitude! Now seventy years after the procedure was drilled into me I still have great difficulty doing otherwise.

Selection upon the convoys’ arrival at Auschwitz.

In “Le savoir-déporté” (édition du Seuil, pages 72-74) Anne-Lise Stern recounts her arrival at Auschwitz in April, 1944:

… Before having time to catch a breath or to think, my friend and I were pushed off to the left, and her husband vanished to the right. There was a fat brute in an SS uniform with a terrifying expression on his face and a whip in his hand. There was also a handsome young man who politely directed the women who were carrying young children or accompanied by them toward the trucks. When there was a grandmother he entrusted the children to her and told the mother, “You, you can walk.” But if the mother became insistent, he would say, “All right, go ahead.” He also asked all those who were tired or ill to go toward the truck. There was still quite a long way to walk. Of the older men and women he asked their age. Above a certain limit – 45 or 50 for the women, 50 or 55 for the men, I believe — they were automatically directed to the trucks. Some people were sorted into one group or the other by sheer chance. One woman was accompanied by two girls, one of them nineteen, the other one twenty-five. The woman was sent to the truck. The older of the two girls insisted on going with her. A good-natured SS said, “As you like.Then another one came up and told her, “You’re quite young; you’d better stay with your sister.”

Some of the young folk, worn out, really were itching to get on the trucks, but we were not sure the trucks would be rejoining us at the camp. We supposed they would go to a camp for children and the aged, where life would be terribly hard for any young people who ended up there. That is why, when the nice-looking man, who was apparently in charge, asked if there were any doctors, pharmacists, or medical students among us, no one spoke up, fearing inclusion in the convoy of old people and children. We were rapidly arranged in rows of five and ordered to take each other by the arm, as the path was rough. Then our column started to move. My friend waved timidly to her husband whose head was visible above the men’s column waiting on the right.

We were never to see any of those who had been favored with the truck ride again…

All this took place took place in an atmosphere of calm and tranquility. The SS seemed quite courteous and peaceful in comparison with the screaming convicts that had first entered the freight cars. While we were being organized they took off the luggage and were berated for being too slow. Never could we have suspected then that we had just been spared a horrible and immediate death.

Français

Français Polski

Polski