Fanny GARREAUD, née AZENSTARCK

Introduction

We are students who are part of a workgroup called “Schüler gegen Vergessen für Demokratie” (Students against oblivion and for democracy) at the Lichtenbergschule high school in Darmstadt, Germany. We were invited by the coordinator of this project, who is also our history teacher, to participate in the “Convoy 77” project and work on the biography of a young French Jewish girl, Fanny Azenstarck, who survived the Holocaust. Our names are Aditi Kolturu, Ella Herron and Charlotte Plechatsch. We are currently in 11th grade and together we wrote the biography of this survivor.

Biography of Fanny Azenstarck

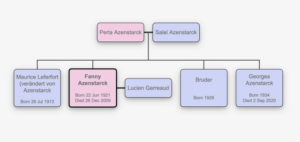

Fanny Garreaud, née Azenstarck, was born on June 22, 1921 in Paris. Her parents, Salel and Perla, both from Eastern Europe, met in France and married on May 19, 1914. Her mother came from a family of economic refugees from Poland and her father had been involved in the Russian Revolution. Fanny had an older brother born in 1915 and two younger brothers born in 1928 and 1934. We only know the name of the younger brother, Georges Azenstarck, who later became a famous photographer and who sadly died in September 2020. We shall talk more about him and his work later in Fanny’s biography.

The family became French citizens by naturalization in 1926. Fanny’s father, Salel Azenstarck, owned a leather goods store in Paris, where Fanny started work in 1937, after completing her apprenticeship. Although the family was from a Jewish background, Fanny’s parents were not particularly religious. At home they spoke Yiddish, which was widely used among the Jewish community from central and eastern Europe. Fanny’s older brother joined the French army in 1933.

A branch of the Azenstarck family tree

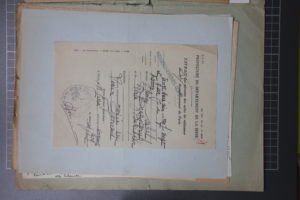

Fanny Azenstarck’s birth certificate

Salel was called up for military service when war was declared but was sent home three months later on the grounds that his body and constitution were too weak. Perla and her two youngest sons sought refuge in Vic-sur-Cère, in the Auvergne region. Fanny and her father left Paris on June 11, 1940. The family moved to the city of Lyon, where Salel and Fanny found work.

When the rest of the family moved to La-Chapelle-Saint-Martin in the Savoie department, Fanny stayed in Lyon and joined the Resistance. She was a member of a group called the Union de la Jeunesse Juive (Union of Jewish Youth) led by Julien Zerman, who was assassinated on December 16, 1943. After his death she joined the MUR (Mouvement Uni de la Résistance or United Movement of the Resistance) and carried out transport-related tasks (messages, letters etc.).

Details included in the obituary of Fanny’s recently deceased younger brother, Georges Azenstarck, confirm that she was in charge of transmitting clandestine messages on behalf of the Resistance.

Photo of Fanny Azenstarck, taken from the records of the Gestapo, who used to identify and arrest her in 1944. (USC Shoah Foundation)

On June 9, 1944, Fanny was arrested, along with most of her Resistance network. The arrest came about because Fanny was identified by means of the photo above. Fanny had gone to rue Burdeau to see a Madame Louise Rampin, who was hiding an arms depot belonging to the Resistance in her house, to collect some letters from the Rhone Social Services department. During the search of the apartment she was arrested by the Gestapo and then held for three weeks, from June 9 through June 30, in Montluc prison just outside Lyon. On July 1, she was sent to the Drancy transit camp, from where she was deported on July 31, 1944 to Auschwitz-Birkenau on Convoy No. 77.

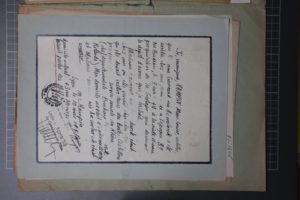

Handwritten letter from Louise Rampin, used in evidence.

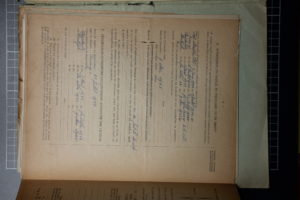

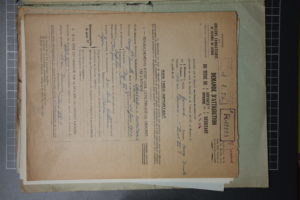

Application for the granting of the title of deported Resistance fighter, including a list of the various concentration camps and the number with which she was possibly tattooed at Auschwitz: A 15 658

The above document is an application from Fanny Azenstarck in 1954 to be recognized as a “deportee resistant”, a deported Resistance fighter. In it, she documents the various stages and periods of her internment in Montluc prison, Drancy internment camp in Paris and the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp, as well as in Kratzau, a sub-camp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp.

The interior of Montluc Prison, near Lyon

In October 1944, Fanny was sent to Kratzau, a sub-camp of the Gross-Rosen concentration camp in Czechoslovakia, where she had to work under the harsh conditions of forced labor, as did some of the other women on the convoy. She only survived the torture because she was given indoor work, as a lathe operator in the factory.

When Soviet soldiers liberated the camp on May 9, 1945, Fanny was one of the survivors, and she then tried to return to France independently (see Régine Skorka’s biography).

In an interview excerpt lasting about five minutes, recorded on June 3, 1996, available on the Institut Français de l’Education (French Institute of Education), website, Fanny recounts the liberation of the camp and how travelled back to France. Unfortunately, we do not have access to the full-length interview, which was carried out by Samuel Grosman on behalf of the witness platform of the USC Shoah Foundation. The liberation process was not, contrary to what was expected and hoped for, quiet and peaceful: in her interview Fanny describes how the Soviet soldiers found a French alcohol depot where they helped themselves. She says that from then on, she knew that it “was going to end badly”. She explains that she only escaped being raped because the Soviet soldier who came for her was dead drunk. She cautiously adds that the other women (now liberated but all weakened by forced labor) could not save themselves from being raped unless they could make themselves understood by the Russians (Régine Skorka did so by speaking in Polish).

To hide from the Soviet soldiers, she and some other people who had been liberated moved away from the subcamp to try to return to France. During the grueling journey, the group spent their nights in deserted train stations, which were still being bombed even then. She managed to make it to Děčín (in today’s Czech Republic), where her group was taken care of by a high-ranking French officer, a former prisoner of war.

The officer places the women under his personal protection. Fanny Azenstarck recounts that the officer forbade anyone from approaching the women, under threat of severe punishment. It was only as a result of this officer’s involvement that the women felt relatively safe around the Soviet soldiers.

This officer helped Fanny and the other women to rediscover a “human aspect”, as their hair slowly grew back. Fanny, who wore US shoe size 6.5 (EU size 35), was given some US size 10.5 (42) shoes, by her “savior”. He also let the women live in a deserted villa, where for three weeks they were fed, given Luftwaffe (German Air Force) pilot uniforms and had real beds to sleep in.

Fanny says that after the three weeks they headed back to France. After much walking, a group of lorries drove them from Saarburg, in Germany, over the border to France.

After her return to France on June 2, 1945, Fanny met up with her parents and brothers, who had remained in Savoie and had survived the Holocaust, most likely with the help of the local villagers. The family returned to Paris, where Fanny continued to work in the leather industry. On October 11, 1947 she married Lucien Garreaud and began a second life, after the Holocaust.

In the post-war years, Fanny visited Israel many times. In 1955 she made a trip to Kratzau. Throughout her life she kept in touch with several ” fellow deportees “. There are some other interviews with the resistance fighter Régine Jacubert, in which she describes the abominable conditions in the Kratzau sub-camp, but unfortunately, we have not yet been able to view them due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are scarcely any documents about Fanny’s life after the war, which makes it very difficult to find information about this period. Her post-war life is not documented well enough to trace where and when she lived with her husband. So far we have not been able to find any further traces of potential children or of her husband, Lucien Garreaud. The date of her death is unclear and only one of our sources states that she died in December 2009.

Request for the title “political deportee“ Request to be recognized as a deported Resistance fighter

Fanny Azenstarck made two requests, to which we had digital access through the Convoy 77 database. She requested the titles “political deportee” and “deported resistance fighter”. In this case we differentiate between ” political/resistance fighter internee” and “political/resistance fighter deportee”. To better understand this, we need to take a look at the following documents:

The envelope of her application for the title of “political deportee”.

Fanny’s application to be recognized as a “deported resistance fighter” confirms a lot of the information that we had already found in primary sources. We were impressed by her beautiful and legible handwriting, in which she filled out and signed the documents.

It also includes her second name, Danielle, her then address in Paris and her profession, which was “confection” (dressmaking and/or alterations). She gave her nationality as French but chose not to fill in the date on which she was naturalized, which was optional. This document also includes the address in Lyon where she was living at the time of her arrest. There was also a line for soldiers to enter the number and nature of any medals they had earned, but since Fanny was not a soldier, she left this blank.

In her request to be recognized as a “deported resistance fighter” Fanny states that she was making the request on her own behalf, by filling in the paragraph “IF THE TITLE IS REQUESTED BY THE DEPORTEE OR THE INTERNEE HIMSELF”. Here she explains her “family situation at the time of arrest”. She was “single” at that time.

Front cover of her application for the title of “deported resistance fighter”, see photo above.

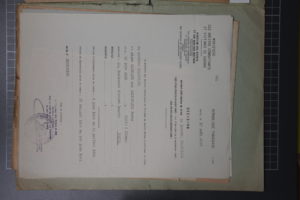

In her application for the title of “political deportee” it becomes clear that she was not applying to be recognized as a “political internee”, but as a “political deportee”, since the word “internee” has been struck out. Once again, she had to enter her name and current address. This time, however, she did not mention her second name, Danielle, but did enter her date of naturalization as March 17, 1926.

It is possible that Fanny did not fill out this application form in its entirety given that the administration already had her previous “deported resistance fighter” request.

Another difference between the two documents is the fact that in the request for the title “political deportee” there is a stamp with the letter “P” in the “space reserved for administrators”. At the bottom of the page, we can see that application was stamped as accepted on June 3, 1959.

Did Fanny Azenstarck ask for compensation for having been a “political deportee” on the same page as she had previously?

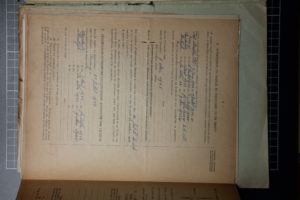

In addition, a document forming part of the application to be recognized as a deported resistance fighter, provided by the Convoy 77 team, includes a handwritten record of all arrests and deportations. At the top, in section B, we can see the “successive places of internment” beginning with Fort Montluc on June 9, 1944, and ending at Kratzau on May 9, 1945, going via Drancy and Auschwitz stations. Since there is a number written by the word “Auschwitz”, we assume that this was her prisoner number and/or her tattoo number?

It was also possible to note on this document whether the person for whom the request was being made was still alive and, if so, when he or she was deported. In the case of Fanny Azenstarck, it states that she was released on May 9, 1945. In addition to this, the “cause” of the liberation, was given as “the Allied advance”. We can thus confirm that she was indeed liberated by Soviet soldiers, as she states in the 1996 interview excerpt that we have in video format.

In section C, at the bottom of the document, it says “DEPORTED TO TERRITORY EXCLUSIVELY ADMINISTERED BY THE ENEMY”. It starts with July 31, 1944, when Fanny was deported from Drancy to Auschwitz, then mentions October, when she was transferred to Kratzau. Here, the difference between “internee” and “deportee” becomes clear. Since she was a French national, she was not held in Montluc Prison as a “deportee” but as an “internee”. It was only when she was put on the last train to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944, that she was classified as a “deportee”.

Places of deportation, on the second page of the application for the title of deported resistance fighter

This difference can is also made clear on the back of one of the documents. It notes that she was registered as an “I.P” (“Interné politique“, or “political internee”) from June 9, 1944 through July 30, 1944 when she was interned at Montluc and Drancy. Then, between July 31, 1944 and June 1, 1945 she was registered as a “D.P.” (“deporté politique” or “political deportee”), this being period when she was in the concentration camp at Auschwitz, then in the subcamp at Kratzau and finally the time it took for her to return to France.

Periods of time for which Fanny Azenstarck was registered as a “Political internee” and a “Political deportee”.

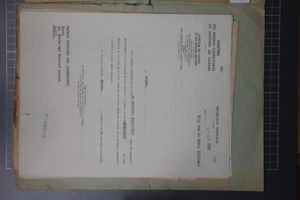

On September 4, the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War wrote to Fanny Azenstarck to confirm that she has been recognized as a political deportee and included the following words: “Please allow me to express my sincerest regards”.

Official recognition of Fanny’s status as a “political deportee”.

On August 17, 1959, the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War confirmed for the first time in an official document that Fanny Azenstarck was a “political deportee”. Once again, we see the distinction made between her time as a “political internee” (from June 9 to July 30, 1944) and her time as a “political deportee” (from July 31, 1944 to June 1, 1945). This document was stamped by the Ministry.

Official recognition that Fanny Azenstarck was recognized as having been a “political deportee” on August 17, 1959.

Note about our work

The sources made available to us on the Convoi77 website helped us enormously with the task of checking and confirming information we had previously found on Fanny Azenstarck. However, we had difficulty classifying and deciphering many of these documents for various reasons. Firstly, French handwriting is quite different from German handwriting. Secondly, some of the scanned documents on the site were difficult to read and sometimes even poorly photographed. Lastly, the fact that the documents were not in chronological order and that some of them were missing did not make our task any easier. Not all photos were available for the request for the status of “deported resistance fighter” and those that were there were not in chronological order. In addition to this, inconsistencies and gaps in the documents confused us somewhat.

Comments on the interview

During the interview, carried out in French, Fanny Azenstarck appears calm. Despite the violence and threats she faced during the liberation and her traumatic experiences, she remains composed, speaks clearly and does not stutter. Even though she often looks straight into the camera, she is not afraid to pause for a moment to lower her eyes or to smile. This does not seem to be nervousness. Her way of speaking gives us the impression of a self-confident person. We also had the impression that talking about these things made her feel good, that it helped her to overcome and work through her atrocious experiences. Watching the interview stirred up all kinds of emotions in us, even though we are not fluent in French. We saw Fanny Azenstarck as a sharp-minded person, a survivor, who had undergone such traumatic experiences in Auschwitz-Birkenau and then in Kratzau. The biography that we have written is not just a story built from a few key dates and events. We had the opportunity to put all this information together and to sketch a portrait of a real person, Fanny Azenstarck.

We encourage you, after reading his biography, to visit the French Institute of Education (“ifé”) website and watch the video of the interview, even if you don’t understand much French. Her emotions are palpable and her message, closely tied to her life story, becomes even more important. We hope soon to be able to access the full version of the interview on the website of the USC Shoah Foundation Washington. Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, this has not yet been possible.

Image library

Contributor(s)

Aditi Kolturu, Ella Herron, Charlotte Plechatsch and Hasset Gessese 11th grade student members of the workgroup “Schüler gegen Vergessenfür Demokratie” (Students against oblivion and for democracy) at the Lichtenbergschule high school in Darmstadt, Germany.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Chères étudiantes, je vous invite à contacter Julie Bronstering, jeune volontaire allemande en stage pour CONVOI 77, pour qu’elle vous mette en contact avec Yvette Lévy, née Dreyfuss, dont le parcours est très proche de celui de Fanny, que vous avez très bien rendu. Yvette est une des rares personnes déportées de notre convoi encore en vie. Sa mémoire est très bonne et elle sera ravie de vous en dire plus sur Fanny, notamment sur sa vie après guerre. Bien cordialement.

Fanny Azenstarck-Garreaud est morte à Paris (11e?) le 26 décembre 2009, selon l’INSEE. Son mari, Marcel, serait mort en 2018, à Ivry-sur-Seine.

https://www.geneanet.org/archives/etat-civil/colgnecminsee/20254608?preview=YTo1OntzOjM6Im5vbSI7czoxMDoiQVpFTlNUQVJDSyI7czo2OiJwcmVub20iO3M6NToiRmFubnkiO3M6MTI6Im5vbV9jb25qb2ludCI7czowOiIiO3M6MTU6InByZW5vbV9jb25qb2ludCI7czowOiIiO3M6ODoicmVsYXRpb24iO3M6MjE6InNlYXJjaF9yZWxhdGlvbl9zdWpldCI7fWNhYzA2NGNlZWM1NDVjMTBmNzJhOTI3YzM1MTMwOWYw

Hi

I am Mikaël Samuel Leferfort-Azenstarck, Fanny’s nephew.

First, I’d like to thank you for your work, it is greatly appreciated, very well done, and I am glad that she won’t be forgotten, her, this dark period of history, and the lessons we need to be learn from all these people. I live in Canada, and the perception of what happen in Europe is quite alarming. I am very thankfull for the work you’ve done.

My aunt is deceased quielty in 2009 at her home in Paris, near Bastille (75011) where she lived since I known her. Her husband Lucien Garreaud died on the 17th of July 2018 at 95 years at “Charles Foix” Hospital (Ivry Sur Seine 94200), he lived in their appartment until the end. They both are at the “Cimetiere Parisien de Bagneux” with my grand parent and my father, Georges Leferfort-Azenstarck.

My father was the last member from this generation of this branch of the family, Fanny and Lucien never had children due to what she suffered at the deportation camp.

Maurice Leferfort was her older brother, he died 30 years ago in Paris, I’ve heard stories, but quite see him very little.

Albert was her other youger brother, he lived in Sueden and died several years ago, I’ve only see him once in my life.

I’ve known my aunt and uncle since my birth, I could tell you about her second life as retired, but could not tell you much about her life before, she was very secretive about it, and that was not the kind of subject we talked about when we see them.

They is not much left from this branch of my family, but if you need more information, please, feel free to contact me.

Cordialy

Mikaël Samuel Leferfort-Azenstarck