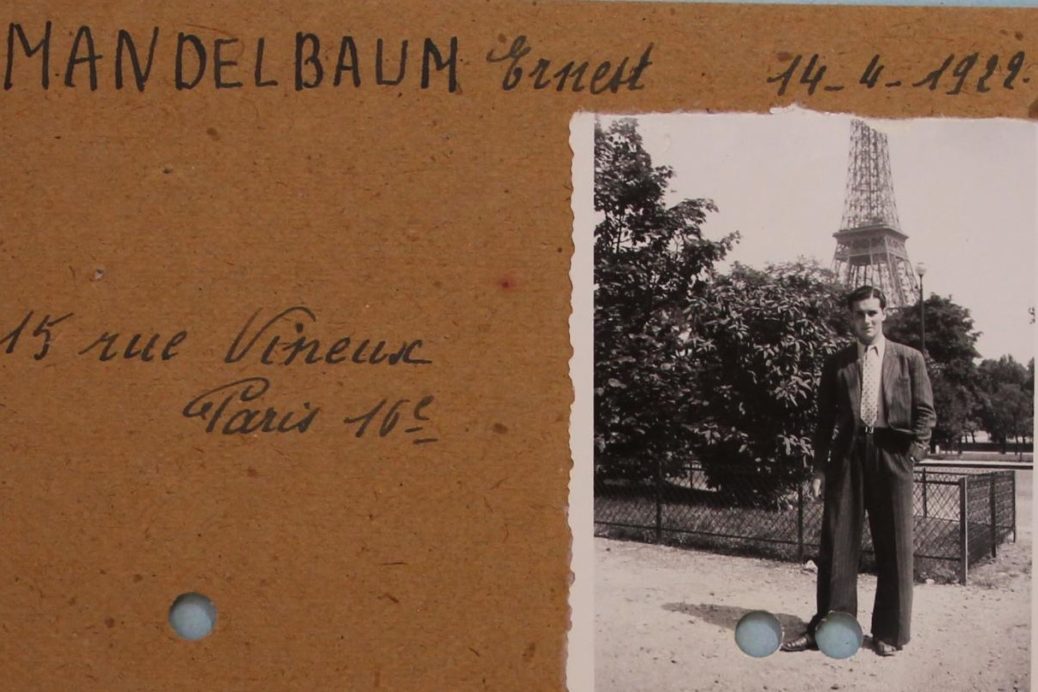

Ernest MANDELBAUM

This undated photo of Ernest, taken in Paris, is from records held by the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen, file No 21P511. Unless otherwise stated, all of the documents reproduced below are from the same source.

Born in Vienna

Ernest Mandelbaum was born on Tuesday, March 14, 1922 at 15, Rotensterngasse in Vienna, Austria. He was the son of Marcel Mandelbaum and Anna Hausotter, who was also known as Anne or Anny, depending on where she was living, and when.

His father was born on November 5, 1890 in Galati, Romania. He was the son of Henri Mandelbaum and Lisse Mandelbaum, née Tikes. Ernest was therefore a Romanian citizen. Marcel was a merchant and prior to 1920 he lived at 19, Tandelmarktgasse in Vienna. In 1944, according to Serge Klarsfeld’s “Memorial to the Jews Deported from France”, he was living in the Château de la Barbière, Mont-Dieu, in the Ardennes, and it was there that he was arrested. He was interned at the Charleville prison before being transferred to Drancy camp and then deported on March 7, 1944 on Convoy 69.

Henriette Wolf, née Mandelbaum, who was born in Antwerp in 1907, and her daughter Ruth, then 11 years old, were deported on the same convoy. They had been arrested in the Ardennes region and transferred to Drancy on February 25, 1944. Marcel Mandelbaum was killed on arrival in Birkenau on March 10, 1944.

Marriage certificate, translated into French on November 26, 1936

Birth certificate, translated into French on November 26, 1936

Ernest’s mother was born Anna Hausotter on November 9, 1902 in Staab in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now Stod, in the Czech Republic. She was the daughter of Henri Hausotter and Julie Hausotter, née Low. Prior to 1920 she lived at 38, Taborstrasse in Vienna.

His parents were married on March 14, 1920 in Vienna. The marriage was performed by Rabbi Armin Abeles at 2, Kluckgasse and witnessed by Hausotter and Emile Walder.

On October 22, 1935, a month after the Nuremberg Laws were enacted, the family had a marriage certificate drawn up by the Civil Registry Office of the Jewish Religious Community in Vienna. Thirteen months later, on November 26, 1936, the Mandelbaum family was in Paris and had this marriage certificate, along with Ernest’s birth certificate, translated into French.

No records remain of the family’s past life in Vienna, but they probably fled the rise of Nazism and anti-Semitism that was taking place there, and decided to seek refuge in France.

Ernest’s early years in France

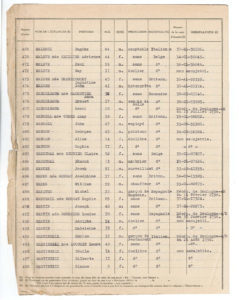

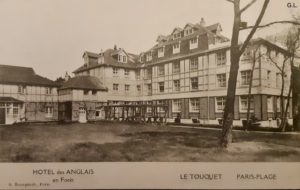

From 1938 on, Ernest lived in Boulogne-sur-Mer in the Pas-de-Calais department of France. His mother and his brother Henri, originally named Heinz, were there with him at the end of 1938. His father, on the other hand, seems no longer to have lived with them. His brother, who only appears in the list of foreigners present in Boulogne-sur-Mer in December 1938, was one year older than him and worked as an assistant waiter. He had been in Boulogne since July of that year. On November 30, 1938, the prefecture issued Ernest with an industrial worker’s identity card. This allowed him to work as a restaurant assistant or waiter, like his brother, at the Hôtel des Anglais in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage. In 1940, Ernest was living at 203, rue de la Tour-d’Ordre, in Boulogne-sur-Mer.

A page from the list of names of foreigners residing in Boulogne-sur-Mer on December 31, 1938. Pas de Calais Departmental Archives, file number M 6816.

Postcard showing the Hotel des Anglais in Le Touquet-Paris-Plage

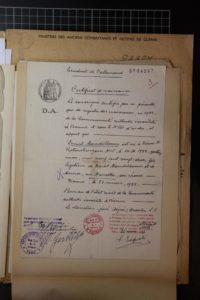

Certificate issued by the prefecture giving permission for Ernest to work, dated December 1, 1953.

In the spring of 1940, in the midst of the chaos of the exodus caused by the German offensive in the north of France, Ernest left the Pas-de-Calais area to take refuge in Finistère, in Brittany, as did many others who did not want to be caught behind German lines. The people of northern France still remembered being trapped there during the First World War.

During the war, in Finistère

Ernest moved with a Mr. Gouzien in Léchiagat, a little town near the port of Le Guilvinec. He stayed there from June 1940 to June 12, 1944, when the German army arrested him during a round-up in Léchiagat.

Perhaps Ernest would have liked to return to Boulogne, but no longer could. The Nord and Pas-de-Calais departments were affiliated to the Military Administration of Belgium and Northern France, and as a result, Jewish refugees were forbidden to return.

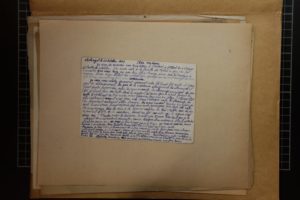

An account of Ernest’s stay in Léchiagat, written by Paul-Jean Berrou, a historian from Bigouden country, was published in the municipal bulletin of Treffiagat in 2017. This is what he wrote, based on the witness statements that he collected:

“Everyone in Léchiagat knew Ernest. Even the children called him by his first name.

Ernest lived alone at the age of 18 in a room near the Saint-Jacques chapel, on the first floor of the studio of the painter, Eugène Gouzien. […]

Ernest spent four years alone in Léchiagat, while his parents, [who were probably separated, and probably lived in Rennes and Paris. His mother came to see him at least once during the war]. Ernest had made many friends. We recognized him in the street among everyone else by his baggy slacks, called golf pants.

As a stateless man, was he really trying to flee from the Germans and the French authorities? Because in Léchiagat itself, there was no Wehrmacht barracks; he chose a good place to stay. […]

Ernest seemed to want to live his youth to the full by integrating into local life just like a Bigouden. Perhaps that is why he did not register in the sub-prefecture before October 20, 1940, as all Jews were obliged to do.

Ernest was said to be carefree, [some less respectful people even called him a Jean-Foutre*]. However, on several occasions when Germans were present in the bars in Guilvinec, he was seen to slip away without a word. He was probably never stopped and checked in 4 years! […] People found Ernest intriguing at the beginning of his stay: he spoke German well, he didn’t work, from time to time he received a money order from his parents, who were no doubt rich. [His wearing silk shirts surprised people by the way] Several young men, probably associated with the budding resistance movement, had searched his house for clues about his supposed relations with the occupiers. He was accused of being a Fifth Columnist. […] When made aware of the suspicions of some of his contemporaries, Ernest quipped his way out of it “The 5th Column? I only know the 6th!”

In addition, in 1942, his home had “been searched by the Germans as part of the crackdown on communists, but nothing came of it,” according to the Director of the Cabinet of the Prefect of Finistère on January 26, 1956.

“Ernest […] must have feared for the worst if ever he were discovered. However, he did not remain hidden like some forced workers in the S.T.O. [Service du Travail Obligatoire] On the contrary! He was thus invited to several weddings. […] Also, he was seen on the stage of the Le Prat dance hall, singing, doing his “turn”. Adopted by the local population, he had adjusted well to life in Léchiagat”.

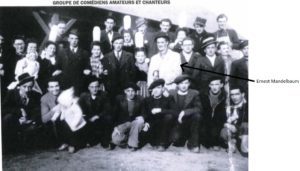

The photograph below attests to this. He was also dating a young girl from Guilvinec.

Copy of an undated photograph of a group of amateur actors and singers, published in the Treffiagat municipal newsletter in 2017.

Source: http://treffiagat.bzh/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/bm2017.pdf

“Ernest was, in addition, a foreign Jew in France and so was obliged to wear a yellow star! Was it known, then, in Léchiagat that he was Jewish? Did people know that Jews were arrested and persecuted? In any event, he was never turned in.

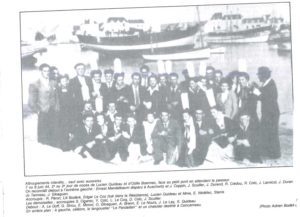

June 6 [1944], the English and American troops landed in Normandy. […]. Curfew declared from 7:00 o’clock in the evening”. Yet, that very same day, two weddings took place between young people from Léchiagat and Guilvinec. Ernest was at the wedding because the groom, Lucien Quideau, was a friend of his. “On Odile Boennec’s wedding day, he told the bride that he would not stay too late. A premonition? Or simply an awareness of the dangers that might arise in the run-up to the Liberation, which was so close.”

Copy of a photograph of the wedding of Lucien Quideau and Odile Boennec on June 7 or 8, 1944, published in the Treffiagat municipal newsletter in 1987. Photograph belonging to Adrien Bodéré, sent by M. Berrou

Note from the Prefecture, from Alain Le Grand’s collection, reference 208 J 24, available online here

In the evening [of June 6, 1944], it seems that an order came from two young FTP (France Tireurs et Partisans) leaders, Alex and Jean Marie from the Rosporden district, asking resistance fighters from Lesconil, Léchiagat and Le Guilvinec to station themselves in the town of Plomeur and to stop the Germans… to help the Allies! Four Germans or Caucasians from Beuzec were arrested and taken to Lesconil.” This episode was described at length by Pierre Jean Berrou in the 1987 municipal newsletter and also by Charles Chalamon on the website “Guerre et Résistance en Pays Bigouden”.

Ernest’s arrest and deportation

On October 25, 1944, Henri Quiniou sent a postcard to Ernest’s mother to tell her about his arrest:

Henri Quiniou’s letter to Ernest’s mother, dated October 25, 1944

As a result of the resistance operation mentioned above, the Wehrmacht combed through two townships and arrested 22 of the 80 resistance fighters who allegedly took part in the action. The four prisoners that had been taken were freed. The German army then sent reinforcements and carried out other raids in the area. Early in the morning of June 12, a round-up took place at Guilvinec and Léchiagat. Ernest was one of the many men of fighting age who were taken prisoner.

Jean-Pierre Berrou noted that “around 2000 men were sent to several enclosures, including the factory courtyard, each of which was easy to watch over. […] Ernest Mandelbaum met a more tragic fate. Found to be a deserter and a Jew during the screening process, he was led handcuffed to a canvas-covered truck […].

Marcel Le Prat recalled that “at the time of the raid” Ernest “via the roof light, hid on the roof of the house where he was staying. No doubt he was spotted.” Corentin Le Marc specified that he “was kept to one side when his identity card was checked.” Ernest could have got false papers quite easily from the secretary of the Guilvinec town hall, Corentin Loussouarn, but he did not chance that approach.

Henri Quiniou and Ernest Mandelbaum were separated from the rest of the people rounded up and sent to the prison run by the Wehrmacht, in the Saint-Gabriel high school in Pont-Labbé, for interrogation. Ernest was then detained in the Saint-Charles prison in Quimper from June 15 to June 30, 1944, and then transferred to Fresnes with other young people from outlying areas. On arrival in Fresnes, he was in good health and his morale seemed good. He remained there until July 19.

Ernest was next sent to Drancy camp, on July 19, where he was held until July 31. There he was given the number 25267 before being deported to Auschwitz on July 31 on Convoy 77. The convoy arrived on the night of August 3 and Ernest’s death was recorded as August 5, 1944, along with those of other deportees who were not selected to go into the Auschwitz camp. No explanation for the death of such a young man, apparently in good health, has ever come to light. Did his health deteriorate during the trip? Or might he have been in the cattle car with Charles Rosenrauch who was planning an escape attempt and whose fellow deportees were gassed immediately upon arrival at Auschwitz?

It was on these same few days in early August that Bigouden country was liberated by the Allies.

A mother’s long battle for recognition

After her son’s arrest, Ernest’s mother contacted Henri Quiniou by mail on August 2 and 5, 1944 and again on October 14, 1944. She even visited Léchiagat, after the war, with her second husband, Henri Riand.

Letter dated June 26, 1946 from Ernest’s mother to the mayor of Treffiagat asking for help in compiling a file relating to personal property damage. This document, from the town hall, was provided by Mr. Berrou.

Certificate from the Mayor of Treffiagat attesting to Ernest’s integrity, dated July 5, 1946.

In reply to Ernest’s mother dated July 8, 1946, the mayor of Léchiagat told her that Ernest Mandelbaum was a young man whose “attitude towards France was perfect and correct” and who was considered to be against the S.T.O (compulsory work service). However, no connection with the Resistance movement had been established.

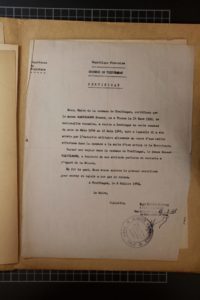

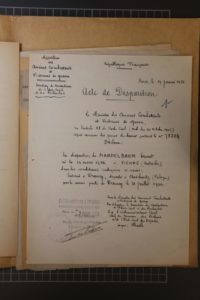

On January 19, 1954, the Civil Registry Office issued a missing person’s certificate. In 1956, the Department of Veterans Affairs and War Victims recognized Ernest as a political deportee and civilian victim. He was posthumously granted the status of political deportee and political internee on June 19, 1956.

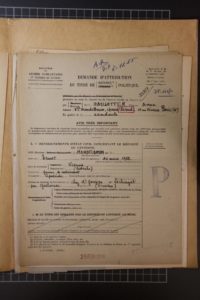

Application for the title of political deportee, December 1955 to February 1956.

Department of Veterans Affairs Missing Persons Certificate dated January 19, 1954

Complete copy of the death certificate issued by the Treffiagat town hall on August 12, 2014

On August 12, 2014, David Chevrier, the mayor of Treffiagat, recorded the death of Ernest Mandelbaum in Auschwitz (Poland) on August 5, 1944, in the municipal civil registers. The request came from the National Office for War Veterans and Victims of War, 70 years after the event.

Image library

Contributor(s)

Mathieu Micault, Literature, History and Geography teacher at the Jean Jaures professional high school in Rennes, with his first year Brevet des Métiers d’Art Horlogerie (A French clockmaking and watchmaking qualification) class.

References

- Guerre et Résistance en pays Bigouden, by Charles Chalamon

Additional information

- *Jean-Foutre – Jean-Foutre is a pejorative expression, used to describe a person, whose skills are highly questionable, or who whose nonchalant and casual attitude towards a situation was annoying.

Français

Français Polski

Polski