A life cut short: Élie Gaston Setbon

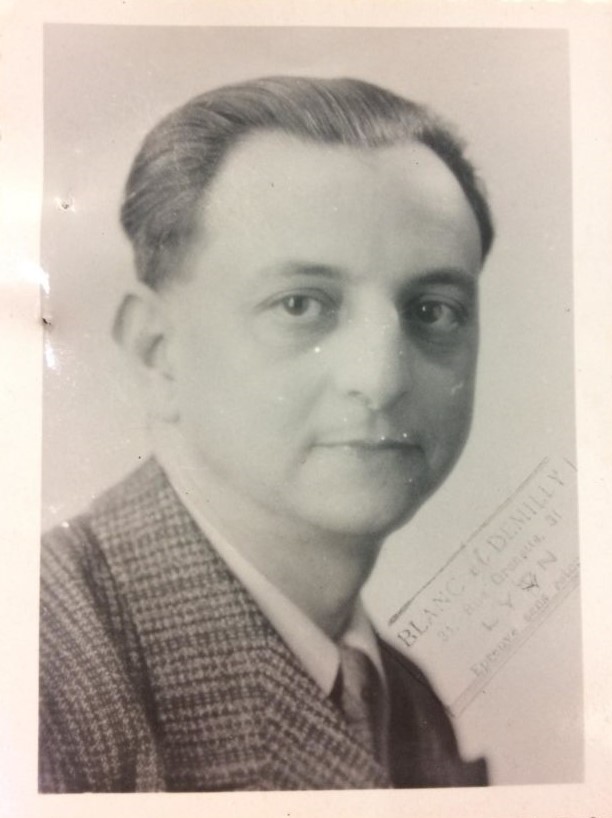

Portrait photo of Elie Gaston Setbon. Source: PAVCC-SHD (the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service in Caen)

by Danielle Laguillon Hentati

Genocide has always been seen mainly a Jewish concern. This struck me very deeply. If hairdressers are murdered, is that only of interest hairdressers? If taxi drivers are killed, is that only a question for taxi drivers? Are such crimes only about the victims and their descendants? Should this not be a shared memory, for all of us?[1]

Élie Gaston Setbon’s life story is not a long one. It relates the life of a man who did not even reach his twilight years. It tells of a life cut short, of a victim of the racist laws of the Vichy regime and of Nazi persecution.

Growing up in peacetime.

Élie Gaston was born on August 19, 1893 in Tunis[2], the capital of the Regency of Tunis, which had been a French protectorate since 1881. His mother was Julie Samama. His father, Raphaël (circa 1863 – 1928), was a merchant based at 51, rue de l’Église, in the heart of the medina in Tunis[3], as was his own father Élie, son of Raphael, before him. Élie Gaston’s destiny was therefore clear: when he finished his education, he too would become a merchant.

While Tunisian Jews continued to play their part in the traditional business of the city, they also began to play an increasingly important role in more modern business[4]. Open to the world, always on the lookout for innovative ideas, they took an active part in both the export and import markets. Élie Gaston thus became part of a trading network between Tunis and Lyon, following in the footsteps of other Jewish merchants of the Regency period.

Lyon, an important trade hub.

Since the early 20th century[5], Lyon had become a hub that fueled a migratory dynamic between the north of Africa and the ancient capital of the Gauls. At a geographical crossroads, with its abundance of capital and a skilled workforce, Lyon became an important commercial center. A transit city, facilitated by its railway network, the capital of the Rhône attracted many Jewish merchants from Tunisia, such as the Boccara family, who had been operating there since the beginning of the 20th century[6].

On the eve of the Second World War, the Jewish presence in France, which can be estimated at between 300,000 and 330,000 people, represented 0.73% of the French population. Most of them were spread between Paris and its suburbs and the Alsace and Lorraine regions, but they were also present in and around Lyon. The 1936 census shows that 6,000 to 7,000 Jews lived in the greater Lyon area, including 4,000 in Lyon itself, particularly in the Presqu’île district, while 2,000 to 2,500 Jews were settled in Villeurbanne[7].

The neighborhoods in which they settled were cosmopolitan. It was therefore in a mixed community, which offered them both work and the safety of life in the Republic, that they chose to live.

In short, in addition to the economic factors that were the driving force behind emigration, other issues were also important: the active solidarity among newcomers, the proximity of families and communities, which was reassuring for new arrivals, and the French authorities who made them welcome.[8]

When he settled in Lyon in 1928, Élie Gaston Setbon was a wine merchant whose main premises were located at 8, rue des Tanneurs in Tunis, outside the medina and in the European quarter, which shows that he had already begun to climb the social ladder.

The year 1928 marked a turning point in his life; he decided to settle permanently in France. He lived at 262, rue de Créqui in Lyon and became a French citizen according to the law of August 10, 1927, which relaxed the conditions for naturalization. He also got married.

After having signed a marriage contract dated August 3, 1928, drafted by Maître Pierre Antoine Marie Lavirotte, a descendant of a long line of notaries in Lyon, Élie Gaston married Maria Francine Regard on August 11[9]. Marie was born on December 15, 1900 in Lyon, where her parents, both natives of the Savoie region, had recently settled. Her father, Joseph Claude (1876 – 1919[10]), was a blacksmith and her mother, Marie Maillet (1879- ?), was a dressmaker. Their witnesses were Ubaldo Consolo, an employee, and Isaac Ben Mussa, a silk manufacturer.

Business in Lyon during the build-up to the war.

During the 1930s, the economy in Lyon was undergoing major changes. The traditional silk weaving industry collapsed, the 1929 crisis having dealt a fatal blow to a sector that had been greatly weakened by changes in the habits of its customers and new international competition. Replacing this industry, the manufacture of a synthetic textile, viscose , had become very significant in the greater Lyon area.

Meanwhile, Lyon had greatly diversified its industrial base and boasted a number of large companies, such as the Berliet car factory, the firms Compagnie Générale d’Electricité and Société Industrielle des Téléphones which had just joined forces to create the most successful cable factory in France. Local heavy industry companies experienced a revival in 1938 with arms orders, as did chemical plants, in particular Saint-Gobain and Rhodiacéta.

As regards transport, Lyon was a major French rail hub. An average of 180 trains per day passed through Perrache the main station at the time. In 1938, more than a million tons of goods passed through Lyon’s railway stations, and 700,000 tons passed through its river ports, mainly via the Saône river.

It was in this highly favorable context that, in July 1929, Élie Gaston increased the capital of the limited company “SETBON & Cie” from 300,000 to 400,000 French Francs. With a general partner and various limited partners, it was a company whose main business was the wholesale trade of wine. Its head office was at 2 bis Quai Saint-Vincent in Lyon.

Élie Gaston was living not far away, at 15, Quai de Serin (now Quai Joseph Gillet) on the left bank of the Saône in Lyon. It was a quiet, socially diverse neighborhood,[11] inhabited not only by professionals, such as engineers and draftsmen, but also by craftspeople, employees, manual workers and laborers. A cosmopolitan district, it was mainly populated by French people, but also by Italians and Russians, as well as a few from other European countries such as Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, Latvia and Poland, and from the north of Africa, including Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia.

The couple had two children, Nicole Juliette (1929 – 2008) and Daniel Raphaël José (1935 – 2010). Élie Gaston opted to integrate the children as much as possible by giving them “normal” first names and sending them to the local French schools.

Perhaps he became French to feel like the heir to a history, to be a custodian of Republican values and to be part of a future to be built together: the right to residence in some way became a right to belong[12].

Wartime

When war broke out, Élie Gaston, like many of his co-believers, chose not leave Lyon, which was both a city of refuge and the center of Judaism in France [13], but which was to turn into a trap. The fate of the immigrant Jews was mixed up with that of all the Jews in metropolitan France and in the then colonies of North Africa[14].

From the autumn of 1940 onwards, the authorities in Lyon rigorously enforced the anti-Semitic policies of the Vichy regime. This State policy was echoed in 1943 by the activity of the Gestapo and its leader, Klaus Barbie. The mass arrests and round-ups carried out by the Germans from February onwards, supported by their French devotees like Paul Touvier, reduced the Jewish population’s scope for survival. On December 31, 1943, Joseph Darnand succeeded René Bousquet, and the stronghold of the Vichy regime was replaced by that of the French Militia. From then on, the impact of the anti-Semitic measures became even more severe and, in the spring of 1944, a wave of violent repression ran parallel to the certainty of Nazi defeat[15].

Despite this change, the advice of the Central Consistory (the executive body of an umbrella organization called the Union des Communautés juives de France, the Union of Jewish Congregations of France) was to remain in Lyon and to “continue to live as normally as possible”[16], a formidable challenge when Jews were considered outcasts, when their future was uncertain and when their hearts were full of fear for themselves and their families. The danger became tangible from 1943 onwards, and all the Jews in the city were aware of it. While some of them changed their lives completely by going underground, others stayed in their homes, in spite of the risks. Was it by choice, due to a lack of resources or knowledge, or perhaps because of an incomplete understanding of the danger and what was unfolding?

On Thursday, June 22, 1944 at 11:45 a.m., Élie Gaston Setbon was arrested by the Gestapo just as he was crossing the Pont Mouton in Lyon, not far from his home[17]. Built in 1847, this bridge stood between the Place du Port Mouton and the Quai de Serin.

Pont Mouton

Later, his wife was to say: “During the occupation my husband had stayed in Lyon, not thinking that he might be caught by the German police”[18].

Has he been denounced as being a Jew? Surely, according to his wife, who wrote: “[…] my husband was the only one arrested although he was with three other people at the Place du Pont Mouton in Serin”[19].

Élie Gaston was first taken to the Gestapo headquarters at 32, Place Bellecour. For Klaus Barbie who was in charge of the crackdown on “enemies of the State”, the orders were clear: on the one hand he was to protect the Wehrmacht against the actions of the Resistance, and on the other he was to participate in the implementation of the “Final Solution”, under the command of Adolf Eichmann.

It is supposed that Élie Gaston Setbon was denounced for money by a certain Richard, who lived in Lyon and was involved in the Gestapo. A certain Martin (who was later shot) would also have been aware of his arrest [20].

As Sylvie Altar wrote, “the hunt [was] all the more devastating because it was organized and very lucrative, with each arrest bringing in between 2,000 and 10,000 Francs for the informer”[21].

Élie Gaston Setbon was incarcerated at Fort Montluc[22] as soon as he was arrested, presumably locked up in the “Jewish hut”, a wooden shack which the Jews were crammed in to.

The site of the “Jewish hut” [23]

He was then transferred to the Drancy internment camp[24], and soon afterwards deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. He was never tried.

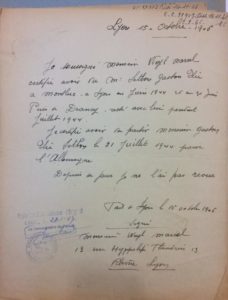

Marcel Weyl’s witness statement[25]

A Dr. Fischer saw him for the last time on October 26, 1944, when he left Auschwitz and was transferred to the Stutthof camp [26]. It is this date that would later be used by the authorities to determine a date of death. The exact circumstances of his death are unknown, but are likely to be similar to those of the majority of people deported to the death camps.

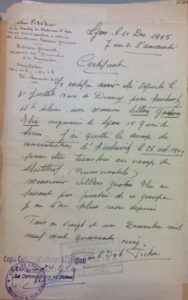

Doctor Fischer’s witness statement

Auschwitz, the impossible word

Each time, I try to say Auschwitz

But the words slip out from under me,

Stealing away the earth that supports my pain,

Imposing a deadly silence on my voice.[27]

On September 3, 1944, the city of Lyon was liberated. Maria Setbon did not take part in the general jubilation, although she did regain a little hope.

Lyon at the time of the Liberation[28]

The people had to be patient while waiting for the gradual return of the deportees, who might bring with them some news or information. In 1945, the announcement of the liberation of the camps, followed by the publication of the lists of repatriated people, rekindled wild hopes amidst the anxiety. However, as the months went by, the deportees’ continuing absence was a source of distress and worry for the families of the “Non-Returnees”.

At home on the Quai de Serin, Maria, while working as a shop manager to raise her children, had a fight on her hands. An interminable journey began with a “Request submitted in order to obtain the rectification of the civil status of a “Non-Returnee””. Until such time as the death of a deportee had been made official and recorded in the civil status registers, families could neither settle their estate nor submit a file to ensure that the deceased was given a title (Resistance deportee, political deportee or political internee) and that the family’s rights be recognized. Such an acknowledgement meant that the widow was entitled to a pension and that the children of the deceased were declared wards of the State.

On November 13, 1945, Maria sent a letter to the Deportation Service of the Ministry of the Interior in Paris to report her husband’s deportation, to inform them of the lack of any “official or indirect news” and to ask to which camp her husband had been deported in order to orient her research. Her letter conveys great dignity, although it was written as a matter of urgency because she had to make decisions for the future of her children. On November 29, 1945, a letter from the Deportation Service of the Ministry of the Interior informed her that every effort was being undertaken to research information. In order to complete the file, she had to fill in the relevant form, attaching two photographs, a birth certificate and a legally authenticated proof of residence certificate. She dutifully followed all the steps: Search for the “Non-Returnee”, report a disappearance, obtain declaration of death Judgment, request the title “Mention Mort pour la France” (Died for France), and finally complete the “Application for the award of the title of political deportee”.

It was only after nine long years of effort and formalities that, on June 28, 1954, Maria was informed by the Ministry of Veterans Affairs and Victims of War that, by virtue of Law No. 52-843 of July 19, 1952 on the improvement of the status of veterans and victims of war, she had been granted a pension of 13,200 francs.

Maria Setbon died on October 9, 1974 in Lyon[29]. How did she live the last twenty years of her life? Did she overcome the trauma of the atrocious death of her husband? The loss of a loved one in such circumstances is a huge blow, a suffering that the lack of a grave cannot alleviate. Very often, after coming to terms with the loss of a loved one, all thoughts turn to the deceased, to what more could have been done, to what could have been said, to the painful deprivation of the missing person. This lack is all the more intense because it is associated with memories that affect both the body and the senses: the sound of the voice, a piece of music reminiscent of a particular moment, contact through touch, images flashing before the eyes, a mere hint of a smell, or a perfume, or the taste of a dish appreciated by the deceased person and shared with him or her. The result can be very vivid and unsettling, stirring emotions that plunge us back into depths of the past.

Did Maria finally accept the death of Élie Gaston? Did she succeed in making plans for the future, without forgetting about her husband? Did she find meaning in her life again, thanks to her children?

If we’d had a grave, a place to mourn you, things might have been easier. If you had come home, debilitated, sick, only to die like so many others, because coming back did not always mean surviving, we would have seen you go, we would have held your hands until they were weak, we would have watched over you day and night, we would have listened to your last reflections, your whispers, your farewells […] And we would have closed our eyes and recited Kaddisch….[30]

References

[1] Henri Borlant, ʺMerci d’avoir survécuʺ, Éditions du Seuil, March 2011, p.177.

[2] Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Historical research bureau of the Ministry of Defense: Political Deportee Dossier of SETBON Élie Gaston, 21 P 538 626.

[3] La Dépêche Tunisienne 24.01.1897.

[4] For this period, see ʺLes Tunisiens israélitesʺ, in Paul Sebag, Tunis. Histoire d’une ville, L’Harmattan, Histoire et perspectives méditerranéennes, 1998, pp. 411-416.

[5] See the work of Sylvie Altar : Être juif à Lyon de l’avant-guerre à la libération (Thèse soutenue à Lyon en 2016) ; ʺÊtre juif à Lyon et ses alentours (1940-1944)ʺ, in : Lyon dans la Seconde Guerre mondiale : Villes et métropoles à l’épreuve du conflit [online]. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2016 (généré le 29 mars 2020). Available on the Internet : <http://books.openedition.org/pur/46932>. ISBN : 9782753555808. DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/books.pur.46932 ʺLes Juifs du Maghreb à Lyon (1900-1945) ʺ in Archives juives 2020/1 (Vol 53).

[6] We had the opportunity to speak with this family. See “Le voyage sans retour d’Abraham Albert Boucara” http://www.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/abraham-boucara/; “La vie brisée de Laure Cohen” http://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/laure-cohen-nee-taieb/; ʺEn mémoire de Dario Boccaraʺ, http://convoi77.org/deporte_bio/dario-boccara/

[7] Sylvie Altar, ʺLes Juifs du Maghreb à Lyon (1900-1945)ʺ, op. cit. p.18.

[8] Sylvie Altar, idem, p.22.

[9] Municipal Archives of the 7th district of Lyon, marriage certificate n°502.

[10] Haute-Savoie departmental archives, Annecy recruitment, class 1896, registration card n°182: record of the death.

[11] Rhone departmental archives, 1931 census of Lyon, Quai de Serin.

[12] Cited by Sylvie Altar: A. Landau-Brijatoff, Indignes d’être français, dénaturalisés et déchus sous Vichy, Paris, Buchet Chastel, 2013, p. 9.

[13] See Sylvie Altar, ʺÊtre juif à Lyon et ses alentours (1940-1944ʺ), op. cit.

[14] Danielle Laguillon Hentati, “Les camps oubliés de la Tunisie (Décembre 1942 – mai 1943)” Presentation made on 16.12.2017 as part of the 2nd Training Session on the exhibition on “The Deceptive State: the power of Nazi propaganda”, organized by the Heritage Laboratory of the Faculty of Letters, Arts and Humanities of La Manouba.

[15] Sylvie Altar, ʺLes Juifs du Maghreb à Lyon (1900-1945)ʺ, op. cit. pp.27-28

[16] Sylvie Altar, ʺÊtre juif à Lyon et ses alentours (1940-1944)ʺ, op. cit.

[17] Witness statement of his widow, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the historical research bureau of the Ministry of Defense, Dossier p.3.

[18] Minutes drawn up on June è, 1951 by André Chosalland, police superintendent of the Vaise district in Lyon, judicial police officer, assistant to the State Prosecutor.

[19] Witness statement of his widow, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the historical research bureau of the Ministry of Defense, Dossier p.3.

[20] Witness statement of Mrs Setbon of November 30, 1945, transcribed as is.

[21] Sylvie Altar, ʺLes Juifs du Maghreb à Lyon (1900-1945)ʺ, op. cit. p.30. Sylvie Altar clarifies (note 84, p.37) : “ The premium increased with the number of people arrested. Charles Goetzmann received 10,000 francs for the arrest of the 13 members of the Touitou family (ADMR 394W313, declaration by Charles Goetzmann entitled “Le boiteux”, January 9, 1948).”

[22] Rhone departmental archives, Montluc 1942-1944, Dossier N°008715.

[23] Source: http://www.patrimonum.fr/montluc/enquete/1_qui-fait-le-patrimoine/3_conserver-et-restaurer/42_les-espaces-remarquables-en-debat-la-baraque-aux-juifs-les-ateliers-le-mur-d-enceinte-et-le-mur-des-fusilles

[24] The date of the transfer to Drancy varies according to the document: June 29 (DAVCC, Dossier SETBON p.3) or July 3 (Research file).

[25] Witness statement by Marcel Weyl on October 15, 1946, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the historical research bureau of the Ministry of Defense, SETBON file. Marcel Weyl was arrested on May 24, 1944 in Lyon as a Jew, imprisoned at Fort Montluc until July 22, 1944, then transferred to Drancy where he arrived on July 24. He was interned there until August 18, 1944, when he was released. His wife, Jeanne Pouchet, was also arrested on May 24, 1944 in Lyon as a “Jewish woman”, imprisoned in Montluc, then deported to Romainville on August 11, 1944. She died on February 21, 1945 in Ravensbrück. Sources: Minutes drawn up by André Chosalland, police superintendent of the Vaise district in Lyon, judicial police officer, assistant to the public prosecutor, following the hearing of Marcel WEYL, dated 8 june 1951. In: DAVCC, SETBON file. Departmental Archives of the Rhône, Montluc Dossier n°3975 of Marcel Weyl, Dossier n°4200 of “Jeanne Weyl”; Municipal Archives of Lyon 2° 1898, mention of the death on the birth certificate of Jeanne Pouchet.

[26] Witness statement of Dr Fischer, December 21, 1945. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the historical research bureau of the Ministry of Defense, Dossier SETBON.

[27] Rachel Franco, Auschwitz, le mot impossible, 31 Janvier 2010.

[28] https://numelyo.bm-lyon.fr/BML:BML_01ICO0010157c2ccb9b89b8?&query[0]=serie_s:%22Lib%C3%A9ration%20de%20Lyon,%20septembre%201944%22&sortAsc=idate&hitStart=6&hitPageSize=16&hitTotal=72

[29] Municipal archives of the 2nd district of Lyon, record of death on her birth certificate, reference n°3273.

[30] Marceline Loridan-Ivens, Et tu n’es pas revenu, Éditions Grasset et Fasquelle, 2015, pp. 59-60.

Contributor(s)

Danielle Laguillon Hentati

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viscose

Lien modifié. Le serveur jewishtraces.org ne donne pas de réponse actuellement, donc je ne peux pas voir s’il y un lien en anglais. J’ai donc mis le lien au page Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klaus_Barbie

Français

Français Polski

Polski