The tragic odyssey of the young Eddy SANDMANN

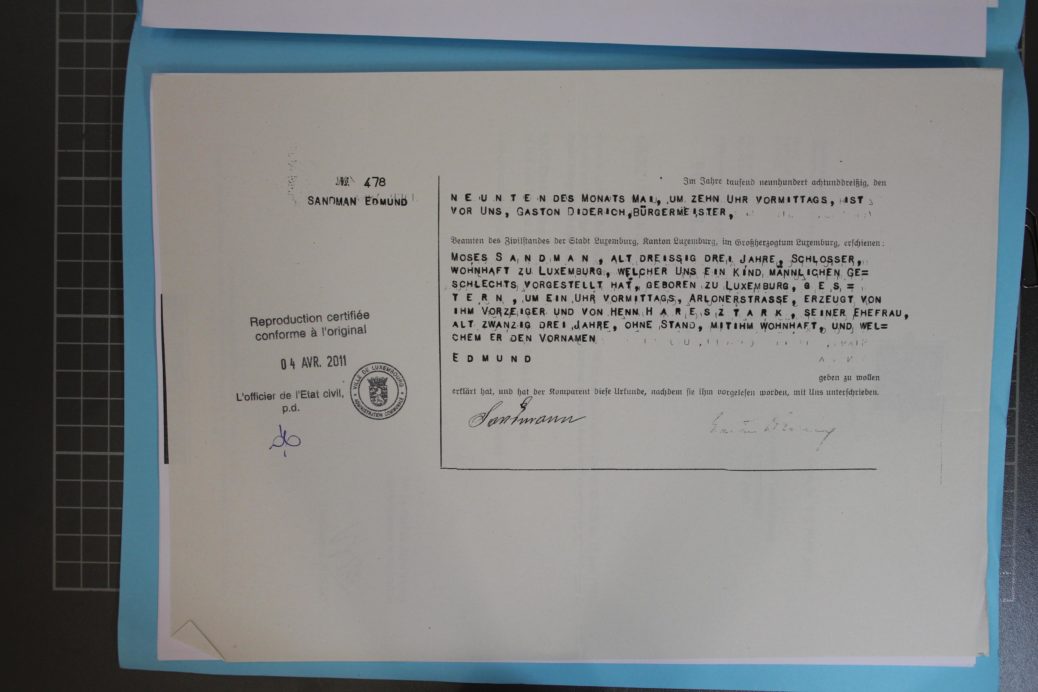

Since we do not have a photograph of Eddy, his birth certificate is shown to the left.

Born in 1938 in Luxembourg, Edmund Sandmann and his parents fled the Grand Duchy, which was then under German occupation, in 1941. In France, a last-ditch attempt to save the young boy from the Nazi’s clutches failed, and in 1944 he was deported from Drancy to Auschwitz.

This biography was written by Laurent Moyse, who has carried out extensive research and wrote an article that appeared in the cultural section (Die Warte) of the main Luxembourg daily newspaper, the Luxemburger Wort. Convoy 77 would like to thank Mr Laurent Moyse and Die Warte for their permission to reproduce this article.

The birth certificate, dated May 9, 1938 and kept in the civil register of the municipality of Luxembourg indicates that the day before, May 8, 1938, at one o’clock in the afternoon, on the road from Arlon to Luxembourg, an infant named Edmund, son of Moses Sandmann, 31, and Hena Haresztark, 23, was born. We learn nothing more from this document except that the father was a locksmith and lived with his wife in Luxembourg. Eddy, as he was later known as, was the pride and joy of his parents, who were married on July 16, 1935 in Luxembourg. The husband, Moses Sandmann, was a Jewish Pole born on February 28, 1905 in Tourka, a small rural town in Galicia, which had a large Jewish population. This area, then under Austrian control, became Polish in the inter-war period and was located at the western most part of Ukraine, not far from the current border with Poland. Moses was the son of Lejzor Sandmann and Pepi Kupferberg, both from Tourka. Like many Jews in this region, Moses decided to leave his native land to escape the misery and hostility to which he had been subjected. In 1929 he went to the city of Stryi (Stryj in Polish) where he was issued a passport on July 11 of the same year. On June 20, 1930, he obtained a visa to travel to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, where he was granted a work permit. He arrived in this small country on July 22, 1930 to join his brother, Wolf Sandmann, who had found a job as an office clerk at the Godchaux brothers’ fabric factory in Schläifmillen. Wolf left his job at the factory shortly after Moses’ arrival, and in August 1930 Moses was hired as a night watchman at the Kockelscheuer gunpowder works. He was a metal worker by profession but, because that would not have provided him with a decent living, he accepted this night work and was later also made responsible for the heating system.

At first, he stayed in the canteen at the powder factory because he was destitute. A report by two Bettembourg police officers, dated December 15, 1934, states that, given the economic crisis affecting the powder factory, he only was only able to work five days a week as a single person, whereas married men, who had families to support, were allowed to work six days. His starting salary was 750 francs per month. The police described Moses Sandmann as a “hard-working, calm and peaceful” employee. In the summer of 1931, he found accommodation in Bonnevoie, at 28 Baumstraße, and stayed there until January 12, 1932. He then returned to Kockelscheuer where he spotted a small two-room apartment with a monthly rent of 120 francs. On June 28, 1935, he moved again, this time to the centre of Luxembourg, to 20 Place Guillaume. In the meantime, he had met a young woman, Hena Haresztark, who had arrived from Poland in early 1935 and was living temporarily with members of her family in the Grund district of the city. Hena was born on 15 July 1914 in Glusk, a Polish village that is now a part of the city of Lublin. She was the daughter of Lejzor Haresztark and Sura Goldberg, both from Glusk. Despite an age difference of nine years, Moses and Hena decided to get married in the summer of 1935. The couple settled in Place Guillaume and Moses continued to work at Kockelscheuer, where he now earned 800 to 900 francs a month. In a report dated January 26, 1939, a brigadier noted that “Sandmann is a very sober man and a regular employee.” He adds that he did not engage in any political activity.

The family home livened up in May 1938 when Edmund was born. The couple’s peace of mind would only last for a short time, however. In Germany, the Nazis, who had come to power in 1933, increased their crackdown and many German and Austrian Jews sought refuge in Luxembourg. In 1939, the most pessimistic analysts were convinced that war was brewing. On May 10, 1940, the day after little Eddy’s second birthday, the Wehrmacht invaded Luxembourg and occupied the country. At the beginning of August, the German civil authorities took over, headed by Gauleiter Gustav Simon.

Fleeing to the free zone

For the Sandmann family, as for other Jewish families who had not been able to escape the country immediately, the mood was heavy with fear. Deprived of their rights, humiliated and gradually isolated from the rest of society, all these people were undesirable from the point of view the occupying forces, who wanted to be rid of them as quickly as possible. One of the first measures the Nazis took was to block their bank accounts. Moses and Hena were denied access to the little money they had laboriously made in recent years and deposited in a savings account (a total of just 2500 francs was in their account at the beginning of 1939). Living conditions became precarious, which also adversely affected the young Eddy. For the Sandmanns, it was therefore essential to leave Luxembourg. That was easier said than done, however, in particular because they had to obtain a special pass before they could leave the country. On January 16, 1941, as part of a convoy of 39 people, Moses, Hena and Edmund Sandmann finally managed to leave Luxembourg for France. They crossed the occupied area and reached the zone administered by the Vichy regime, which was under the authority of Marshal Philippe Pétain. However, on October 4, 1940, this collaborationist regime enacted a law according to which prefects were authorized to intern foreign Jews in “special camps”. Being of Polish nationality, the Sandmanns were therefore a target the authorities. After spending a few months in Marseille, they were arrested and interned in the Rivesaltes camp.

Eddy became unwell and was taken to the nearest hospital, in Perpignan. Hena, his mother, feared for his life. Her son’s remoteness weighed heavily on her and she turned to the Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants, a Jewish children’s relief organization, that endeavoured to rescue children from the internment camp and place them in children’s homes. The OSE had an office in Rivesaltes and, with great difficulty, managed to place a significant number of children in residential homes, most of which were located in central France. Each week, Hena went to this office and begged the staff to put Eddy in a nursery.

An unrecognizable child

As Eddy regained his health, the OSE tried to have him discharged from hospital but only succeeded in doing so in February 1942. The plan was to include him in a group of children who were to leave Rivesaltes and to be sent to the Creuse department. A few days before his departure, Hena, who hadn’t seen her son for months, was granted special permission to go to visit him in the hospital. She walked the eight kilometres between the camp and the hospital. When she arrived in Perpignan, she found Eddy in a desperate state: he spoke incomprehensible gibberish, did not even recognize her as his mother and could barely walk. She was deeply distressed. On the day of his departure, Eddy was released from the hospital and was put on the train from Perpignan. The train stopped for just three minutes at Rivesaltes station to allow the children from the camp to board and find their seats. Given the circumstances, Hena was allowed to go to the station to kiss her son goodbye. She saw him again for a very short time amidst the tumult of the departing children. According to Vivette Samuel, who then managed the OSE’s office in the Rivesaltes camp, “Eddy’s face looked like that of a pale wax statue that had been kept in the dark for too long”. The frail boy was taken to the Chateau of Chabannes at Saint-Pierre-de-Fursac in the Creuse department. The child was apparently suffering from a prolapsed rectum. The director of the children’s home was reluctant to take him in, since medical care was not easy to provide in a community of a hundred or so children. Eddy’s stay in this home, managed by a former printer and journalist, Félix Chévrier, who was assisted by a highly motivated team, was very beneficial. The friendly atmosphere there gave him such a zest for life that in a photo of him that was sent to the Rivesaltes camp in May 1942, he was unrecognizable. According to Vivette Samuel, “This was a remarkable resurrection. We were told that he was cheerful and boisterous. He had become very handsome. His mother wept with joy”.

Her delight, however, was to be short-lived. Roundups of foreign Jews in the free zone began in the summer of 1942. Internment camps were filling up with a view to deporting Jewish families. The internees from Rivesaltes were first transferred to the Drancy camp, just outside Paris, and then deported to Auschwitz. Eddy Sandmann’s parents were among them. Hena was deported on the convoy of September 11, 1942 (we were unable to find any information about Moses). Pierre Laval’s government used a decree about family reunification as justification for the Vichy authorities to track down children as well. The OSE responded by trying to move children out of residential homes to prevent them from being taken. The managers took them to Marseille and made the necessary arrangements for them to emigrate to the United States. However, the war had reached a turning point. In November 1942, the Americans landed in North Africa, while Nazi Germany extended its occupation to the southern part of France. From then on, for all those who had been unable to leave France, deportation loomed large. Members of the OSE bent over backwards to try to save as many children as possible. They placed them with foster families and gave them a new identity when the residential centers became unsafe.

In March 1943, Eddy was entrusted to the Savarin family, who lived in the Indre department. He spent a little over a year there, but in May 1944, some indiscreet remarks put him in danger. He therefore had to be moved on yet again it was decided best to smuggle him into Switzerland. Eddy was by now six years old. He was taken to Lyon, where he was to spend the night, waiting to cross the border the next day. Sadder still, he was housed with a Jewish family, the Halimis, who were arrested that same night. The following morning, when someone arrived at the house to take him to a safe place, the apartment was empty.

Transferred to Drancy camp, the young Eddy was deported on July 30, 1944 on the last large convoy to take deportees to Auschwitz. As it happened, he was in the same wagon as another child from the Grand Duchy: Marcel Handzel, born in Esch-sur-Alzette and nine years old at the time of his deportation, and his mother, as recounted in his biography published on this website (see also Die Warte, November 23, 2017). The rescue operation was unsuccessful, just as the Americans landed in Normandy and, along with their allies, began to liberate France. As it had been for his parents, Eddy’s deportation to Auschwitz was a one-way journey.

Sources:

- Civil status document, municipality of Luxembourg,

- Luxembourg National Archives, police des étrangers (Police Dept. for foreigners), dossier no 219416

- Vivette Samuel, Sauver les enfants, éditions Liana Levi, 1995, pp. 202-204

- Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, Le mémorial de la déportation de Juifs de France, Paris, 1978

Contributor(s)

Laurent MOYSE

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Très belle bio, mais qui ouvre sur des questions. Eddy a effectivement été arrêté avec les parents et les 3 enfants Halimi. Est-ce une coïncidence affreuse? La personne qui a amené l’enfant était-elle suivie? Quel était le réseau de sauvetage? Pourquoi les Halimi, juifs nés en Algérie, dont le père de famille était un ex employé des Postes, hébergeaient-ils un enfant juif? Avez-vous des informations complémentaires? (le village où vivaient les Savarin, par exemple?)