In memory of Dario BOCCARA[1]

Photo of Dario BOCCARA from the Shoah Memorial in Paris

by Danielle Laguillon Hentati

Honorary Professor of Italian and author

Chevalier des Palmes académiques

Dario Boccara was one of the “ultimate” victims, those drowned in the multitude of forgotten faces that were not saved by chance or exceptional circumstances.[2]

To tell his life story is an almost impossible challenge. The intimate experiences of the deportees who died, were executed and murdered at Auschwitz are extremely difficult to access: their physical disappearance, the lack of graves, the oblivion in family and individual memories, the absence of documents all constitute obstacles that are sometimes insurmountable.

Usually, when carrying out research into a person who died during deportation, various sources are available to the historian or genealogist: civil status records, censuses, prison records, and sometimes camp registers, records of war victims held at Caen [3], the Yad Vashem Memorial, historical works and various Internet sites. On the other hand, a small number of survivors gave oral or written testimonies, such as Primo Levi, whose book Si c’est un homme [4] has stirred people’s consciences. Finally, indirect testimonies, accounts by relatives or people involved in the war period between 1940 and 1943, have recalled the circumstances of some of the arrests, and even the deportees’ backgrounds. In particular, Mireille Boccara’s account Vies interdites[5].

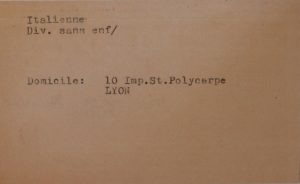

In the case of Dario Boccara, however, the sources are quiet. Four documents were found: the Drancy file, two testimonies given at Yad Vashem and a police report from Dijon. A file found by chance in the archives in Dijon offered hope for more information, but it turned out to be that of another man with the same name [6].

Since it was not possible to reconstruct his story in its entirety, all avenues had to be explored before putting together the pieces to gain a better understanding of Dario Boccara’s life.

In Tunisia

Dario Boccara was born on 30 August 1915, according to various sources [7], but his birth certificate has not been found in either the archives of the Israelite Community in Tunis [8], or the civil status records of the diplomatic archives in Nantes [9]. Since he came from a family of “Granas”, Livorno Jews who had been living in Tunis since the middle of the 17th century [10], and thus would have retained his Italian nationality, his birth was probably registered in Italy [11]. His father, Daniel Boccara, lived in Tunis, where he was born in 1855 and died around 1939[12]. Is he the same man as the Daniel Boccara, a fabric merchant, who obtained a passport in 1918 in Tunis? Is he the same Daniel Boccara, a sorter, living at 7, Place Saint-Clair in Lyon, who bought a knitwear business at 73, rue de Bonnel, called “Au déluge de coupons” in 1930, then sold it again in 1934[13]? No doubt, given the family history and his son’s career.

His mother was Rebecca Cohen, sister of Ines who was the wife of Elie Lalou Boccara [14]. Married in around 1905, Daniel and Rebecca had seven children: Régine, Emma, Ninette, Félix, Claire and Yvonne. Dario was the fifth of the siblings.

It is safe to assume that Dario had a quiet and happy childhood that was spent “in this living continuum of language and the sharing of tastes and rhythms, amidst the heady scents of spices, ripe olives, jasmine and orange trees, in the blue shadow of the great illuminated eucalyptus trees of the municipal garden, where they walked on the shores of the Gulf or on the heavenly hill of Sidi-Bou-Saïd”[15].

As a man, Dario was a merchant and he lived on avenue de Londres in Tunis. He was married [16], and then divorced[17] quite quickly, it would seem. Was that the reason that he left Tunisia for France?

Document from the FN ref. 75130-BOCCARA_Dario_FN_75130_DAVCC_copyright_0013

In France

In June 1939, Dario was in Dijon. On business? As a tourist? On June 22, 1939, he was arrested in the city by the police “for violating the decrees of May 2 and 14, 1938 (lack of foreigner’s identity card)” [18]. Referred to the Court in Dijon, he was imprisoned, but was finally released on bail. In the same report, a note in the margin indicates that he was “Unknown on the Central File”, which suggests that this was the first time he had been arrested.

The audit of the “undesirables”

In the inter-war period, the need to implement a rational policy for the control of immigration and “undesirables”[19] became an obsession for a number of experts and lawyers. The decree of April 2, 1917 introduced an identity card for foreigners, which bore a photograph. Successive decrees specified its use, including the decree of February 6, 1935, which limited the use of the identity card to the department in which it was issued. Implemented as an emergency measure, the decree-laws of May and November 1938 relating to the Police for Foreigners were intended to set out in full the rules governing the entry and residence of aliens in France, in particular by limiting the duration of identity cards to three years, with the possibility of renewal.

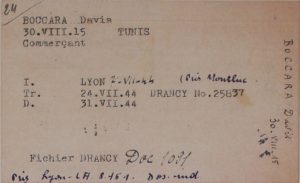

Dario Boccara had therefore contravened these requirements. A youthful indiscretion? No doubt, because he subsequently lived in compliance with the law at 10, impasse Saint Polycarpe in Lyon [20]. This was a quiet building inhabited by families of low-income workers: a laundrywoman, a storekeeper’s boy, a carpenter, a salesman, employees, a fitter and a nurse. When Dario came into contact with them, he no doubt felt at ease, perhaps even accepted.

The Boccara family in Lyon

The Boccara family had been based in Lyon since the beginning of the 20th century.

Along with his father Youda, and then his brother Jacques, [Élie Lalou] Dario took part in all the international exhibitions in France, Belgium, England, Italy and Switzerland. Their base remained in Tunis, where they hired their staff and bought their goods. The war brought them to Lyon during the International Urban Fair of 1914. They opened a shop in rue de l’Hôtel-de-Ville, their first foothold in France. When peace was restored at the end of the war, they continued their life as exhibitors and opened a chain of oriental carpet shops in Paris, Strasbourg, Nice, Vichy and Aix-les-Bains, until their separation in 1923, when they were enjoying great success [21].

From then on, Élie Lalou was to expand his business, in particular by manufacturing high-end carpets in Iran. “The period between the wars [was] a prosperous time for the firm, which sold up to 12,000 carpets a year!”[22]. One can suppose that after the incident in Dijon, Dario opted to move to Lyon, where he knew he could count on the help of his numerous and active relatives. Did he benefit from the support of Élie Lalou to get a job? It seems likely, because he always lent a hand to family members. He was the person of reference; the charismatic personality of the family.

The shop É. Boccara, Tapis d’Orient (Oriental carpets), Place Bellecour in Lyon, 1930s[23]

Arrest

Although, in the absence of any records, the circumstances of Dario’s arrest are unknown, the reason for it is likely to be the same as that of the other members of the family: the hunt for Jews.

After the invasion of the southern zone on November 11, 1942, Lyon had been subjected to severe repression, due to the strength of the local Resistance movement and the fact that it was a regional capital for the German enforcement authorities as well as for the French Militia.

The Boccaras and their associates, however, had confidence in the French Republic, which, thanks to the Crémieux decree of 1870, had granted French nationality to their grandfather Eliaou, born in Constantinople and later settled in Tunis.[24]. Élie Lalou’s daughter recalls:

I explained my opinion to my father:

– The conduct of the Germans is barbaric! At the time of the Inquisition, we had the choice between being burnt at the stake or conversion. They haven’t even given us that option!

He was standing in front of the fireplace in the living room. His face suddenly collapsed. His eyes were sad.

– I am sorry, Mireille, to hear you talking like that. If I had the choice, I’d choose the Concentration Camp and perhaps death rather than denial. I am old. I could die tomorrow. That my family may be saved, that is all I ask of God [25].

A policy of repression and persecution

Lack of awareness? Naivety? Blindness ? The Boccaras were either oblivious to the danger or minimized it. In the occupied city of Lyon, the German repression authorities (the Gestapo, notably Klaus Barbie[26], the SS and the Feldgendarmerie) and the French Militia, led in 1943-1944 by Paul Touvier[27], were to pursue an appalling policy of repression and persecution. It was in this context that, on November 20, 1943, the arrests of the family members began. First of all, it was Élie Lalou Boccara, who was arrested at his home, at 18 Place Bellecour, for “anti-German activity”[28], along with his brother-in-law, Armand Cohen, who was tortured for acts of resistance, before being shot on November 24, 1943 in the basement of the Ecole de la Santé in Lyon. Next, it was Dario David Ossona, a trader, arrested on March 7, 1944 in Lyon as a “black marketeer”[29]. Then it was the turn of Jacques Jacob Boccara, a refugee from Strasbourg to Tassin la Demi Lune, where he was arrested on May 2, 1944 together with his children, Henri and Simone Emma. Next, Abraham Albert Boucara, arrested as a Jew on June 26, 1944 in Lyon[30], then Laure Cohen, arrested on July 5, 1944 in Lyon as she was visiting a friend [31]. All were to die in the Nazi camps.

Dario Boccara was the last of the family to be arrested in Lyon on July 7, 1944, and imprisoned in Montluc [32] where he languished in a cell for three long weeks. Did he know that any of his relatives were close by? On July 24, 1944, he was transferred from Montluc to Drancy [33].

Document from the FN ref. 75130-BOCCARA_Dario_FN_75130_DAVCC_copyright_0013

Drancy

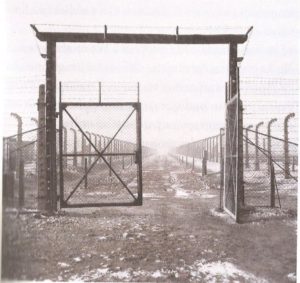

From August 1941 to August 1944, Drancy internment camp was the hub of the anti-Semitic deportation policy in France. Beginning in 1942, as Nazi Germany turned towards the Final Solution, Drancy changed from an internment camp to a transit camp, and was the last stop before deportation from the train station at Le Bourget (in 1942-1943), then from Bobigny (1943-1944) to the Nazi extermination camps, primarily Auschwitz.

On March 27, 1942, the first convoy for the deportation of Jews left Drancy for Auschwitz [34].

Source : Wikimedia

The journey to Auschwitz

July 31, 1944. The last large deportation convoy of Jews left Drancy for Bobigny railway station bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. This convoy has all the typical characteristics of those that were organized in a hurry, in the face of the predicted defeat of the German army. This convoy transported 1321 people crammed into cattle cars. Among them were 324 children and infants, which led Lucia Park, Dario’s niece, to say that she had been “deported with the children”[35].

On the train, men, women and children were unable to move, lie down or sit down. They remained standing, motionless, frozen in their distress, sharing the same misery. It was better to remain silent, as words would make their suffering even more intense.

Someone suddenly yelled out from one end of the wagon to the other […].

“This is it,” said the man.

The shouting stopped abruptly. A nightmare, who knows, but we had to shake the guy. When it’s something else, the fear, it lasts longer. When it’s anguish screaming, when it’s the thought of dying that screams, that lasts longer….[36]

The heat was always high on those early August days. Bodies became clammy, clothes stuck to the skin. Embarrassed to breathe, gripped by the premonition of certain death, Dario probably thought that he could no longer endure this senseless journey. Did the idea of escape occur to him? Was he aware of any plans for escape? Did he adhere to them? But no opportunity arose, as the SS kept watch, even stopping the train to check for possible openings in the floors and ceilings of the wagons.

During the night of August 2 to 3, after three days and three interminable nights, they came to the end of their journey: Birkenau.

The entrance to Birkenau[37]

We were torn from our restless sleep by the deafening squeal of the wheels locking.

Suddenly, there was the alarming crash of doors opening onto the blinding glare of powerful spotlights. There was an urgent shout: “Alle raus! Schnell! Schnell! ” (Everyone out! Quick! Quick!). In the widespread panic, we had to hurry out, abandoning our belongings [38].

Did Dario understand that he was entering into hell? He must have. The blinding lights, the deafening howls in an unknown language and the angry barking of dogs on a leash caused overwhelming terror. German soldiers beat them with their whips to terrorize them. This simplified their task, so they would not have to answer questions.

The selection

As soon as they stepped off the train, along the “Judenrampe” (the Jews’ platform), the deportees were selected: by sex, by age and according to their apparent ability to work. The others were eliminated. Of the 1321 deportees who arrived in Auschwitz, more than half were immediately directed to the gas chambers, including Dario Boccara.

As he was so young, only twenty-nine years old, a question arises: Why was he executed as soon as he arrived? He could have worked. Various hypotheses are possible: did he try to escape during the journey? Was he sick? Was he injured? This might explain the selection that befell him on arrival.

Malahamoves[39], “Angel of Death” came by. Of convoy No. 77 of July 31, 1944, comprising one thousand three hundred and twenty-one people, including three hundred children between the ages of two and sixteen, two hundred and nine were counted as survivors, including one hundred and forty-one women.

Conclusion

Today, aggressive anti-Semitism, and racism in general, is resurfacing in Europe; we who have listened to the witnesses, but also heard the voices of the dead, must not turn our heads away. We are the messengers and guardians of the story of Dario Boccara, of all those like him, of all of the deportees. For, as Élie Wiesel said at the Barbie trial in Lyon:

“No justice is possible for the dead. And the killer kills twice. The first by killing, the second by trying to erase the traces of his crime. We have to prevent the second death, because if the second death takes place, then it will be our fault.”[40]

The messengers must also see to it that these tragic stories form a basis for reflection on “that school of destruction of humanity”[41] that was Auschwitz. I echo the words of Henri Borlant, the only survivor of the six thousand Jewish children under the age of sixteen deported to Auschwitz in 1942:

I also reflect a great deal about the meaning of crime against humanity. In law, this crime affects humanity in general, but in practice I must point out that it is often the Jews who take the initiative to raise this subject. […] Is such a crime only a matter for the victims and their descendants? Should this not be a collective memory?[42]

[1] Article for the Convoi 77 Association.

[2] Béatrice Pasquier, Disclaimer, in: Shlomo Venezia, Sonderkommando, dans l’enfer des chambres à gaz, Trad. by Béatrice Prasquier, Preface by Simone Veil, Albin Michel, 2007, p.17.

[3] Ministery of Defence, Historical Service, Archives of the Division of Victims of Contemporary Conflicts (DAVCC) at Caen, deportees’ dossiers.

[4] Primo Levi, “Si c’est un homme”, trans. by Martine Schruoffeneger, Paris, éd. Audiolib, 2015.

[5] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, Collection of Witnesses’ Testimonies of the Holocaust, Fondation for the Memory of the Shoah, Editions Le Manuscrit, 2006.

[6] My thanks to Françoise Darmon, who kindly sent me the scanned file.

[7] Date mentioned on the Drancy file, on the “Witness statement” of Brigitte Judith Cohen-Hadria, his great-niece, at Yad Vashem; it is also on the wall of names: http://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/notice.php?q=identifiant_origine:(FRMEMSH0408707149920); date shown also in the report of the commissioner of the Dijon mobile police, dated 22.06.1939, National Archives at Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, in a box file numbered : 19940434/424, from the Security Police Archives, known as the Moscow Archives.

[8] Email from Moché Uzan, rabbi of the Jewish community in Tunis.

[9] Email from Gervaise Delaunay, from the diplomatic Archives dept. in Nantes.

[10] Paul Sebag, Les noms des juifs de Tunisie. Origines et significations, L’Harmattan, 2002, p. 46 ; Elia Boccara, La saga des Séfarades portugais. Tunis : un havre pour les familles fuyant l’Inquisition, Tchou, 2012.

[11] Research is ongoing.

[12] Family tree of Lucien Ktorza: https://gw.geneanet.org/lctorza?n=boccara&oc=&p=daniel

[13] Le Salut public 1930/09/27; Le Salut public 1934/07/17.

[14] See : “Le voyage sans retour d’Abraham Albert Boucara”: http://www.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/abraham-boucara/

[15] Hubert Haddad, “D’ailes et d’empreintes” in: Une enfance juive en Méditerranée musulmane, Unpublished texts collected by Leïla Sebbar, Bleu autour, 2012, pp.175-176.

[16] The marriage certificate was not found in Tunis, as stated in an email from Moché Uzan, Rabbi of the Jewish community in Tunis.

[17] He was said to be “divorced” on the Drancy file but, “single” on the “Witness Statement” of Brigitte Judith Cohen-Hadria, his great-niece.

[18] National Archives at Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, Carton 19940434/424, Report of the 11th regional Brigade of mobile police at Dijon, dated June 24, 1939. My thanks to Françoise Darmon, of the CGJ, who kindly sent me this report.

[19] Emmanuel Blanchard. Les ”indésirables”. Passé et présent d’une catégorie d’action publique. GISTI. Figures de l’étranger. Quelles représentations pour quelles politiques ?, GISTI, pp.16-26, 2013.hal-00826717.

[20] Departmental Archives of the Rhone, Lyon, impasse Saint Polycarpe n°10, census of 1936.

[21] Mireille Boccara, op. cit., p.73.

[22] “Boccara, la continuité”, Lyon Presqu’Ile / 4 mars 2014 : http://lyonpresquile.com/author/admin/

[23] Source: Mireille Boccara, op. cit., p.30.

[24] See Mireille Boccara Cacoub, Le fusil d’Élaou, Publisud, 1994.

[25] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, op. cit., p.151.

[26] In November 1942, Klaus Barbie took command of Section IV: Fight against the Resistance, Communists, Jews, etc.. In February 1943, he became head of the Gestapo in the Lyon region. Nicknamed “the Butcher of Lyon”, he ordered the execution of many hostages and the deportation of thousands of Jews to Drancy. He would not be tried until 1987, at the end of a long hunt all the way to Bolivia. On July 4, 1987, the Rhône Assize Court found Klaus Barbie guilty of seventeen crimes against humanity and sentenced him to life imprisonment “for the deportation of hundreds of Jews from France and in particular the arrest, on April 6, 1944, of 44 Jewish children and 7 adults at the children’s home in Izieu and their deportation to Auschwitz”.

[27] Paul Touvier was called to Lyon in 1943 where he was regional chief of the second militia service. In this capacity, he took part in the persecution of the Jews and the fight against the resistance fighters. On September 10, 1946, Paul Touvier was sentenced to death in absentia by the Court of Justice of Lyon (a special court set up at the time of the Liberation), and on March 4, 1947 to the same sentence by the Court of Justice of Chambéry. In 1971, President Georges Pompidou granted him a presidential pardon, but this measure revived the legal proceedings. He was finally arrested on May 24, 1989 at the Saint-Joseph priory in Nice and was to appear before the Yvelines court of assizes in Versailles from March 17 to April 20, 1994, for complicity in crimes against humanity. Touvier was sentenced, like Klaus Barbie, to life imprisonment on April 19, 1994.

[28] Departmental Archives of the Rhone, Montluc 10/1 dossier n°1156.

[29] Departmental Archives of the Rhone, Montluc 16/3 Dossier N°1874; Shoah Memorial; Mireille Boccara, op. cit.

[30] Danielle Laguillon Hentati, ”Le voyage sans retour d’Abraham Albert Boucara”: http://www.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/abraham-boucara/

[31]Danielle Laguillon Hentati, “La vie brisée de Laure Cohen”: http://www.convoi77.org/deporte_bio/laure-cohen-nee-taieb/

[32] His file was not found in the Rhône Departmental Archives. His name does not appear in the list of resistance fighters’ files.

[33] Drancy Dossier N°25837, sent by the Association Convoi 77.

[34] Wikipedia: https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_de_Drancy

[35] Lucia Park “Witness statement” à Yad Vashem : https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=en&s_lastName=boccara&s_firstName=&s_place=&s_dateOfBirth=

[36] Jorge Semprun, Le grand voyage, Éditions Gallimard, 1963, p.38.

[37] Source: Henri Borlant, “Merci d’avoir survécu”, Éditions du Seuil, 2011, p.83.

[38] Jérôme Scorin, L’itinéraire d’un adolescent juif de 1939 à 1945, Imprimerie Christmann, Nancy, 1994, p. 129. My thanks to Serge Jacubert who kindly sent me a few pages of this book.

[39] Shlomo Venezia, op. cit., p.88.

[40] Cited by Thomas Petit, Les ressorts symboliques du politique : LE PROCES DE KLAUS BARBIE, 11 mai 1987 – 4 juillet 1987, Un moment d’émotion: le procès d’un nazi pour crimes contre l’humanité. http://thomas.petit.gr.free.fr/Mes_travaux_Master_Barbi3.htm

[41] Henri Borlant, “Merci d’avoir survécu”, Éditions du Seuil, 2011, p.109.

[42] Henri Borlant, “Merci d’avoir survécu”, pp. 176-177.

BOCCARA Dario 1 Fichier Drancy

BOCCARA Dario 2 Magasin Bellecour

BOCCARA Dario 3 Fichier Drancy FN idem ci dessus

BOCCARA Dario WIKIMEDIA image generique DRANCY

BOCCARA Dario 4 Birkenau image generique

Contributor(s)

Danielle Laguillon Hentati, Honorary Professor of Italian and author, Chevalier des Palmes académiques

Français

Français Polski

Polski