Charlotte Schuhmann (1931-1944)

Photograph of Charlotte Schuhmann taken in around 1940.

Biography written by the 10th grade students of class 12 from the Lycée Louis Vincent high school in Metz, France, followed by students’ comments. School year 2019-2020.

Our class

We are the 36 10th grade students of class 12 from the Lycée Louis Vincent, a high school at 3, rue de Verdun in Metz, France. From our classrooms, we can see just a little further down the street, at number 10, the building where Charlotte Schuhmann lived until 1940. This part of the street is now called rue Leclerc de Hauteclocque. Our high school celebrates its 100th anniversary in 2020. It used to be a vocational school, so Charlotte would not have attended it, but she would often have walked past its impressive facade.

With the help of our teachers, we dedicated a lot of time and effort to this research project, which allowed us to get to know this young girl who died at the age of only 13. We had moving encounters with Mr. Henry Schumann, Charlotte’s first cousin and then with Mr. Robert Frank, Charlotte’s childhood friend. We read and analyzed the many documents provided by Mr. Schumann and several archives services. We carried out research at the Metz municipal archives office and read excerpts of Primo Levi’s work during the commemoration of the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz camp. Finally, we wrote the different sections of the biography, which we were able to piece together over time.

Three important witnesses

Three important witnesses played an essential part in this work.

-

The first of these witnesses is Mr. Henry Schumann.

Born in 1947, Mr. Schumann spent his entire childhood in Metz, some of it at 12, rue de Verdun, in the building next to the one where Charlotte had lived before the war. His father, Pierre Schumann, was the younger brother of Levy Schuhmann, Charlotte’s father. The original surname Schuhmann was changed to Schumann after the war. In this biography of Charlotte, we have kept the original spelling Schuhmann for Charlotte herself and for the family members who did not survive the war.

He was kind enough to come to see us on September 23, 2019 to tell us Charlotte’s story and to present the research he has undertaken about his cousin. While he had heard about Charlotte when he was younger, it was only after the death of his parents, in particular after his mother’s death in 2001, that he became interested in her story. He found letters from Charlotte sent during the war and some photos of her, her brother and her parents. He then spent a great deal of time trying to get to know this cousin he had never met. He now feels very close to her and thinks of her as an older sister.

Following his very moving presentation in our classroom, he delved back into his family archives and found some additional documents that provided us with a great deal of information. A few weeks later, we had the joy of sharing his excitement when he met Mr. Robert Frank, Charlotte’s childhood friend.

Photograph of Mr. Schumann

-

Our second witness is Mr. Robert Frank

Mr. Frank at our school on November 22, 2019, showing us photographs of his parents, who died as deportees.

Born on November 11, 1929 in Metz, Mr. Frank has lived in Paris since the end of the war. He came to tell us his story and that of Charlotte on Friday, November 22, 2019. Before meeting him, we understood that he had known Charlotte but we did not know that the two families were friends and saw each other often. Indeed, before the war, the Frank family lived at 29 rue Pasteur, which is very close to rue de Verdun. As far as we know, he is the only person able to give us any details about her.

In 1940, the two families took refuge in the Charente Maritime department (then called Charente Inférieure), in the west of France. The Frank family lived in Royan for a few months and the Schuhmann family in Les Boucholeurs. It was through the librarian at the Dunant secondary school in Royan that we were able to make contact with Mr. Frank.

In the autumn of 1940, along with eight other Jewish families from Metz, the Schuhmanns and the Franks met up at Festalemps, in the Dordogne department. The two families were arrested during the round-up at the Angoulême Philharmonic Hall in October 1942. Mr. Frank and Charlotte were then separated, and their paths crossed only occasionally after that. Mr. Frank is the last survivor of this round-up.

-

Our last important witness is Mr. Richard Niderman

Originally from Forbach, in the Moselle department, Mr. Niderman was born after the war. For several years, he has been researching his brother Joseph and his sister Charlotte, two children who were separated from their parents and shuttled around for over two years before being deported. Strangely enough, they had the same first names as the Schuhmann children. In retracing their steps, he came across documents that mentioned Charlotte Schuhmann several times. His brother and sister had crossed paths with her from 1942 to 1944, in Angoulême and the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews) children’s homes in Paris. A friend of Henry Schumann, he put together a folder especially for us. He gathered all the documents and information that he had found about Charlotte. This saved us a lot of valuable time. From Israel, where he lives, he continued to follow the progress of our work. It was through our research on Charlotte that he was able to meet Mr. Frank.

Photograph of Mr. Niderman (on the left) with Mr. and Mrs. Franck, taken during their first meeting in Paris in January 2020.

Thanks to these three major witness reports, we were able to reconstruct Charlotte’s brief existence. After a peaceful childhood in Metz, her life was completely turned upside down by the Second World War.

Charlotte’s peaceful childhood in Metz, from 1931 to 1939:

A family from Poland

Born at the Belle-Isle Hospital in Metz on January 12, 1931, Charlotte, although both her parents were Polish, was declared a French citizen on February 6, 1931. A law passed in 1927 allowed foreign parents to have one or more of their children born in France recognized as French.

His father, Lévy Schuhmann, born in 1899, had been living in Metz since 1920. Like his father, he was a “Haushirer”, a Yiddish word for a travelling salesman. They both bought their supplies from Mr. Kaufmann, a tailor in the rue des Jardins, and on weekdays they went to sell suits and garments in the villages around Metz. This trade enabled them to earn a living and to live in the sought-after district known as the Nouvelle Ville (New City). To supplement his family’s income, Levy sometimes rented out a room in his apartment for a few weeks or months.

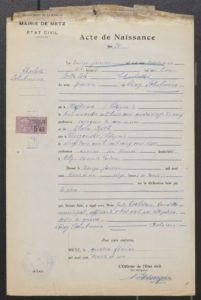

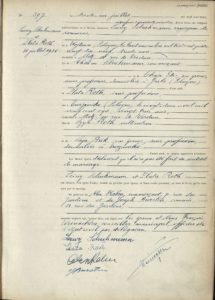

Charlotte’s birth certificate, dated January 12, 1931 included in her naturalization papers (French National Archives)

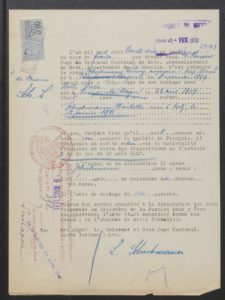

Declaration of French nationality for Charlotte Schuhmann, dated February 6, 1931 (French National Archives)

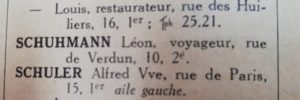

| Extract from the 1935 Moselle directory (Metz Municipal Archives) |

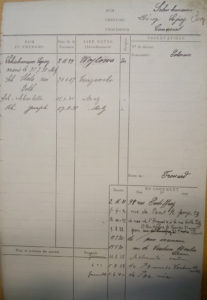

Lévy Schuhmann’s address record. It shows that before 1920, he was living in Frouard. (Metz Municipal Archives)

Lévy and Zlata Schuhmann’s marriage certificate, dated July 31, 1930 (Metz Municipal Archives).

In 1930, he married Zlata Roth, who was also born in Poland, with whom he moved to 10, rue de Verdun. Zlata, who did not work outside the home, took care of their daughter Charlotte, who was born the following year, and their son Joseph, born on August 27, 1938. Unlike Charlotte, Joseph was not naturalized as a French citizen. Pierre and Cyli Schumann, Levy’s younger brother and sister-in-law, lived at 6, rue des Bénédictins. Their daughter Denise was born in 1938, like Joseph. The geographical proximity between the two couples undoubtedly explains Charlotte’s deep attachment to her aunt and uncle.

We know very little about Charlotte’s childhood. However, the few photographs and documents that we do have, give us some clues. Mr. Frank was also able to share his memories with us.

A loving family

All the family photographs show a happy and united family in which the children were pampered. Mr. Frank remembers some very happy birthday parties where the children were very spoiled. He remembers afternoon games on the Esplanade de Metz and the Île du Saulcy.

Zlata Schuhmann and her two children, Charlotte and Joseph

Charlotte and Joseph

Joseph

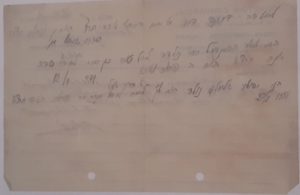

One particularly moving document was found by Mr. Schumann on the eve of Mr. Frank’s visit to Metz. On the back of a message addressed to her uncle Lévy by his supplier, Mr. Kaufmann, Charlotte’s father had inscribed in Yiddish the Hebrew first names of the children, given as is customary for Jewish children at birth, and their dates of birth.

On the back of Mr. Kaufmann’s letter to Lévy Schuhmann dated September 1, 1936, Mr. Kaufmann wrote in pencil the first names and birth dates of his two children:

– Charlotte: Breindel, born in the month of Thèvet (Tevet)

– Joseph, known as Jojo: Yeouchoua Alexander born in the month of Menachem Av

Strong family values

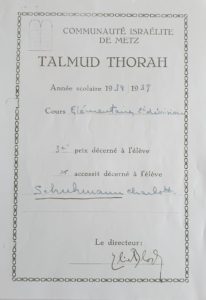

Aside from the father’s love for his children, this document suggests that the Schuhmann family remains very committed to Jewish values. Mr. Henry Schumann kept at home a certificate signed by Rabbi Elie Bloch in 1939. In second grade, Charlotte was awarded third prize in religious education.

Certificate of religious education awarded to Charlotte Schuhmann by Rabbi Bloch in 1939.

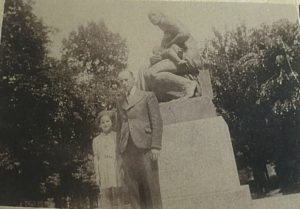

Two photographs of Charlotte with her father, which appear to have been taken on the same day, the first in front of the Metz war memorial and the second beside the statue dedicated to French mothers on the Esplanade, show the family’s attachment to their new homeland and their desire to integrate into it.

A Photo of Charlotte with her father, in front of the War Memorial in Metz.

A photo, probably taken on the same day, in front of the statue dedicated to French mothers, on the Esplanade.

A photo, probably taken on the same day, in front of the statue dedicated to French mothers, on the Esplanade.

A serious young girl

The Schuhmann family lived close to the girls’ school, now the Georges de la Tour high school. There are no records to confirm that Charlotte attended school there. According to Mr. Frank, Charlotte was a very intelligent girl who impressed him with her knowledge as well as her seriousness. We can infer from this that she was a good student. The careful writing and spelling of her letters during the war confirm this, as well as the third prize for religious education. Mr. Frank also explained to us that she was a well-brought up young girl and that her parents were strict with her. She had a strong character and was extremely polite. She had an independent character and did not like to be upset. In some situations, when she reacted firmly to defend or justify herself, she was well able to argue with him.

This peaceful life in Metz came to an end at the beginning of the Second World War. Like many Jewish families in Lorraine, the Schuhmann family was obliged to move around a lot during the conflict.

The Schuhmann family moved around (1939-1942)

A few weeks in Bulgnéville (autumn 1939)

According to Mr. Frank’s account, at the beginning of the war, in September-October 1939, or perhaps as early as mid-August when the prefecture encouraged the residents of Metz to leave town if they could, his father and Lévy Schuhmann, fearing for the safety of their families, decided to send them to shelter elsewhere. They therefore sent their wives and children to Bulgnéville, in the Vosges department, where they shared the same house. It was during these few weeks that Charlotte and Robert’s relationship deteriorated, perhaps due to the absence of their fathers or an understandable anxiety about the future. This also strained the relationship between their mothers. Robert Frank recalls that at the age of 10, he was the “strong man” of the house. As such, he was in charge of fetching jugs of water from the center of the village. Charlotte was sometimes asked to help him, but she did not like to be ordered about and he had great difficulty getting her to undertake this chore.

There is no trace of this stay in the Bulgnéville municipal archives. Mr. Frank thinks that they stayed there only a short time and that the families returned to Metz when it appeared that there was no danger because there was no actual fighting during the “phoney war”. He also thinks that his family left Metz at the end of 1939, unlike the Schuhmann family, who seem to have stayed on longer.

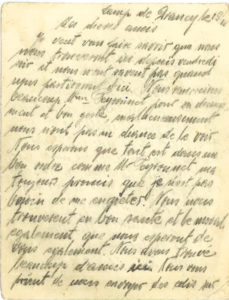

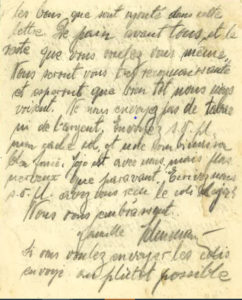

Les Boucholeurs, in Charente-Maritime: spring-autumn 1940

It seems that after their return from Bulgnéville, the Schuhmanns settled back into their house on rue de Verdun. Henry Schumann found an electricity bill paid by his uncle on May 6, 1940. It was probably when the phoney war ended and the Germans were approaching Metz that the Schuhmann family left the city for the village of Boucholeurs in Charente-Maritime. It was from there that Lévy Schuhmann wrote a letter in German to his brother Pierre dated June 10, 1940 (which Pierre received while he was a prisoner of war). From what he wrote in this letter, Lévy seemed to have only recently arrived. In fact, he explained to his brother, among other things, that he had enrolled Charlotte in the village school that very morning. The family was also worried about their luggage, which had still not arrived. He also mentioned that he had discovered the nearby town of Châtelaillon-Plage and had visited the Frank family who had taken refuge in Royan. This is the only trace we have of the family’s time in Charente-Maritime.

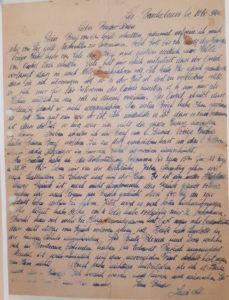

Letter written by Levy Schuhmann to his brother, Pierre, on June 10, 1940, from Les Boucholeurs.

In October 1940, the Atlantic coast became a prohibited area for Jews, it was at this point that the Schuhmanns and the Franks met each other on a train and then travelled in a truck to the village of Festalemps in the Dordogne department.

Festalemps: autumn 1940- 8 October, 1942

The little village of Festalemps was home to a dozen or so Jewish refugee families from the Lorraine and Alsace regions. The Schuhmann family lived outside the village in a house belonging to a Mr. James Peyronnet, called Le Chêne Vert (The Green Oak). It was a huge house of nearly 3000 square feet (270 square meters). The Frank family lived about 100 yards away. The families were very close, even though Robert and Charlotte were always fighting. Accustomed to a comfortable life in the city, they now discovered what it was like to live in the country. The children went to school in the village. We can assume that Levy Schumann, like his friend Mr. Frank, worked in the fields.

Le Chêne Vert (old postcard provided by M. Alain Peyronnet). Mr. Frank thinks he remembers that the Schuhmanns lived at the back of the house.

Henry Schumann kept a postcard sent to his uncle Levy by his aunt Régina from the ghetto in Krakow in July 1942. On it, she gave news of her family.

The Dordogne Departmental Archives office sent us a copy of a census of foreigners living in Festalemps dating from July 1942. Curiously, Charlotte was considered Polish, whereas her brother was not mentioned as a foreigner. This census was no doubt a precursor to the round-up which took place in October 1942.

List of foreigners living in Festalemps in July 1942 (Dordogne Departmental Archives).

Festalemps was in occupied Dordogne. As such, the village fell under the Charente department at the time. It was located only a few miles from the Free Zone. James Peyronnet’s brother, Fernand, ensured that three of the ten Jewish families present in the village crossed the demarcation line. It is unclear why the Schuhmanns and the Franks did not try to flee.

This spell in the country was a very happy time for Mr. Frank. It was probably the same for Charlotte. Henry Schumann has two letters written by Lévy Schuhmann from Drancy: one is addressed to the Peyronnets, whom he calls “My dear friends”, the other was probably also intended for them. Both show the Schuhmanns’ genuine affection for and total confidence in the Peyronnets. They lived in the same house for about two years and one imagines that Charlotte might have played mother or teacher to the two boys in the family, who were about the same age as Joseph. This happy time ended, however, in a dramatic fashion.

A child separated from her loved ones: Angoulême (October 1942 – June 1943)

The roundup in Angoulême: October 8 and 9, 1942

On the night of October 8-9, 1942, in common with the six other Jewish families still living in Festalemps, Charlotte’s family was arrested by the French police. Mr. Alain Peyronnet, then two years old, recounts that his father James Peyronnet tried to intervene, at the risk of being arrested.

Commemorative plaque at Festalemps, erected on the initiative of Mr. Frank, in May 1998.

The families were taken by bus to the Angoulême Philharmonic Hall, where 442 Jews from all over the region were gathered. Mr. Frank explained to us that the living conditions during the roundup were horrible. There were only two toilets, which were clogged from the first day, there were no beds and very few chairs, people of all ages, from infants to the elderly, were crowded together, making an appalling noise which was amplified by the poor soundproofing of the hall. He also spoke of the cold of the night, the collection of valuables by the SS, and of everyone being afraid and worried. This round-up was the beginning of the long road that led almost all these people to their deaths. 387 of them were transferred to Drancy and then deported to Auschwitz.

Those who stayed behind were of French nationality, Charlotte was one of them. Mr. Frank explained to us that the French children had been separated from their family members who were still foreign nationals. The German police requested the fathers to accompany their children to a courtyard with papers attesting to their nationalities. Thus Lévy Schuhmann had to take Charlotte to the courtyard before re-joining his wife and son in the hall. One can easily imagine Charlotte’s anguish at being separated from her family for the first time.

Depiction of the Angoulême roundup, by Lucile Bossuet.

Charlotte separated from her family

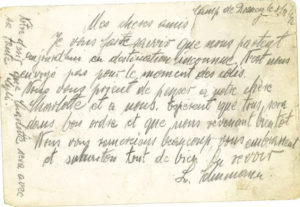

Charlotte probably had no more news of her parents and her brother, who had been transferred to the Drancy camp. However, her father did write two letters from the camp.

The first was dated Monday, October 19. He said he had arrived at the camp on Friday (i.e., the 16th, a week after the round-up). It was apparently intended for the Peyronnets. Levy did not know when they would be able to leave, but he reassured his friends that the family was in good health. He thanked Ms. Peyronnet for her “dedication and good deed”. We know from Robert Frank that between the time the police woke them up at about 6 in the morning and the time the bus arrived, the families had just an hour to gather together their belongings. One can suppose that Ms. Peyronnet gave the Schuhmanns groceries, helped them with their luggage or took care of dressing, making lunch and soothing the children, who must have been traumatized, especially Joseph, who was only four years old. Lévy specifically pointed out that Jojo was with them and that he was less anxious. The separation from his big sister must have disturbed him more though. Lévy also asked her to send parcels with some bread (with ration coupons that he included in the letter) as well as a neck warmer and a blue jumpsuit.

The first letter written by Levy Schuhmann in Drancy on October 19, 1942

The second letter is dated November 3, 1942, i.e., the day before departure for Auschwitz. From Room 2 in Block 1, Stairwell 1, Levy wrote to James Peyronnet and his family to say that they would be leaving “for an unknown destination”, so they no longer needed parcels, thanked them for their help and said goodbye. He asked them to think of them all and of Charlotte. The last words he wrote were for her: he hoped she would be able to reach her aunt Cyli. This is further evidence of the links between the two families; it was the Peyronnets that the Schuhmanns were thinking of before leaving Drancy. The next day, Lévy, Zlata and Joseph left on convoy 40. Clearly, they all died on arrival at Auschwitz.

The second letter written by Lévy Schuhmann in Drancy, on November 3, 1942.

The Bon Pasteur orphanage (October-December 1942)

After leaving the Philharmonic Hall, Charlotte was sent to the Bon Pasteur Catholic orphanage on rue de Paris in Angoulême. According to the register kept by the nuns, it was in November that 21 French Jewish girls between the ages of 2 and 16 were sent there by the Prefecture’s refugee committee. If the date given by the nuns in their register is correct, a few weeks would have passed between the round-up and Charlotte’s admission to the Bon Pasteur orphanage. We do not know where she was during that time.

The nuns explained that “the rooms on the ground floor and the first floor of the St Michel washhouse were hastily converted into workrooms and dormitories.” This building was destroyed during a bombing raid in July 1944.

They also noted that the girls only stayed there for two months, because the Rabbi of Poitiers then placed them with French Jewish families. Charlotte left the orphanage on December 15.

Extract from the Annals of the Notre-Dame de Charité du Bon Pasteur community in Angoulême, year 1942, listing the young girls admitted to the orphanage. The column on the right shows the date of each girl’s departure.

With the Feingrütz family: December 1942 – June 1943.

Charlotte lived with the Feingrütz family at 37, boulevard Denfert Rochereau in Angoulême, as of December 15, 1942, when she left the Bon Pasteur orphanage. The Feingrützs were a French Jewish family who took in Jewish children. Henry Schumann still has two of the letters written by Charlotte to her aunt Cyli. The first one dates from the beginning of her stay on January 10, 1943 and the other was written on June 1, 1943, a few days before her departure for Paris.

In the letter that Charlotte wrote on January 10, 1943, she tried to sound reassuring. She explained that she was working hard to obtain a diploma (perhaps a religious study certificate), that the Rabbi of Angoulême came to give religion classes on Thursdays and Sundays and she expressed her joy at having received a card from her uncle Pierre, Cyli’s husband, and another from a great-uncle in Metz, Victor Schuhmann. She also mentioned her parents and her little brother, explaining that she would like to see them and that she missed them, especially as it was two days before she turned twelve years old. This was the first birthday she had spent away from them. Of course, she did not know that they had been deported and that they were already dead. From her words and meticulous handwriting, we can see that she was a serious and studious child.

She asked her aunt to send her a few things such as some clothes, a fine comb and some cotton. Beyond these simple requests, we can see the difficulties of daily life during that time of great shortages. She also said that she was in good health and thanked her for caring about her. Her language towards her aunt and her cousin Denise was very affectionate.

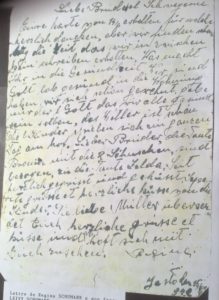

Charlotte’s letter to her aunt , dated January 10, 1943

In her letter of June 1, 1943, Charlotte appears anxious: she was distressed to have had no news of her parents and brother. She also explained that the Feingrütz family had no news of their son. She again expressed all her affection for her aunt and Denise. She was replying to two letters from them. She shared their concern about their husband and father who has not received their latest letters. She urged her aunt to reassure her daughter. She shows herself to be deeply caring and compassionate.

Her aunt had suggested that she come to Bellac, in the Vienne department, where she had taken refuge. This appears to have been a source of great concern to Charlotte. She mentioned that her papers were not in order and spoke of the risk for herself and the Feingrütz family of her ending up in the “hospital” if she went about trying to get them. On the back of the letter, Mrs. Feingrütz also raised the issue of the papers and expressed her fear of going the same way as Charlotte’s parents.

Charlotte was a few days away from her examination scheduled for June 10, 1943, but did not seem certain she would be able to take it. Did she already sense what was going to happen to her a few days later? Was her official status really so worrying? Had she already been told that she would be leaving for Paris? For whatever reason, she appears to have been greatly perturbed.

Charlotte’s letter to her aunt, dated June 1, 1943 On the back, the note from Madame Feingrütz to Madame Schuhmann.

The UGIF takes over (June 1943-July 1944)

The UGIF gathers together the children (June 1943)

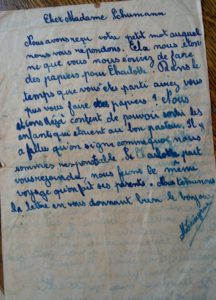

The UGIF, (Union Générale des Israélites de France, or Union of French Jews), which had been created by Vichy in 1941 at the request of the Germans, was an organization in charge of social welfare and of representing the Jews. According to Joseph Niderman’s witness statement, on June 6, 1943, the UGIF gave the order that all Jewish children in the Charente department, including those in the Free Zone, be sent to Paris. The children were first gathered together in warehouses or halls in Angoulême. Joseph Niderman speaks of some 150 children and adults who were locked up for two days in extremely crowded conditions. On June 9, 1943, they arrived in Paris.

The Lamarck center (summer 1943)

In 1942, the UGIF opened various children’s homes. The children, who would normally have been destined to go to Drancy, thus escaped certain death, at least temporarily. Along with a few other children from Metz, Charlotte was admitted to the Lamarck children’s home in the Montmartre district of Paris on June 9, 1943. She was registered under the number 976. At the age of only 13, she joined a group of children with whom she must have made friends.

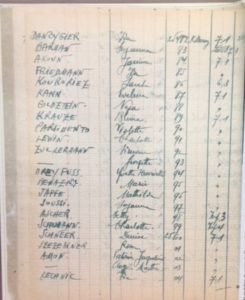

Register of arrivals at the Lamarck Center on June 9, 43. Charlotte was the last child to be registered. She was declared to have been resident in Festalemps.

These copies are not legible, but you can read them clearly in the photo gallery at the end of the biography.

A spell in Louveciennes

On September 3, 1943, Charlotte was one of a group of children sent to a sister orphanage in Louveciennes.

Register of arrivals at Louveciennes on September 3 1943.

Mr. Niderman recalls that, in her testimony filmed for the INA (Institut National de l’Audiovisuel, the French National Audiovisual Institute) and the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah, in 2016, Félicia Barbanel explained: “We were at the Lamarck center and, because we were not in very good shape, they sent us to Louveciennes. It was in the countryside, it was beautiful, it was amazing. We were happy, we were in the open air, we were fine. The food was good. The director was also Jewish, a Mr. Louy, with his wife, and his daughter… And then, well, we even had a little party there. We sang, we danced, some people recited poems… We spent a month in the country.”

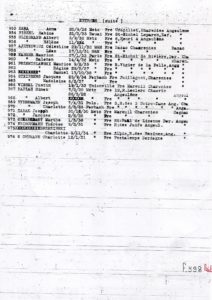

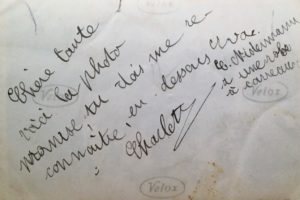

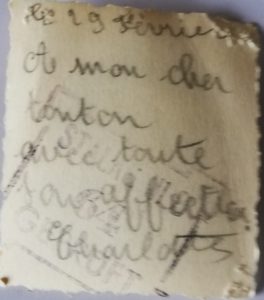

Was it on the day of this little party that the photograph still kept by the Schumann and Niderman families was taken? On the back of this photograph is the last known message that Charlotte sent to her aunt Cyli. The reference she makes to Charlotte Niderman suggests that the girls were friends and had perhaps known each other for quite some time.

Again, according to Mr. Niderman’s research, the testimonial of Denise Holstein, a 17-year-old teacher, provides insight into the lives of the 22 children. There were as many as nine beds in the large bedrooms. The older children welcomed the younger ones and become monitors; they showed them a lot of affection while trying to make them listen.

The photograph that Charlotte sent to her aunt. (Charlotte is in the middle of the second row)

The note on the back of the photo Charlotte sent to her aunt.

After this “enchanted interlude”, Charlotte returned to the Lamarck Center on October 6, 1943..

The return to the Lamarck center and to the Lucien De Hirsch school (October 1943 – July 1944)

Register of arrivals at the Lamarck center on October 6, 1943.

Once back at the Lamarck Centre on October 6, 1943, it was time for the start of the new school year. The children went to the Lucien de Hirsch Jewish school on Secretan Avenue in the 19th district, which was also managed by the U.G.I.F. The children walked to the Antwerp subway station and from there took the metro, where they had to ride in the last car, as was obligatory for Jews under the anti-Semitic legislation.

The last known photograph of Charlotte was taken around this time. It is a passport photo that she sent to her uncle Pierre Schumann in February 1944. He was taken prisoner of war during the defeat of France in 1940. He was held in Stalag III B, in Fürstenberg sur Oder. He kept this picture of his niece and passed it on to his children.

Photo of Charlotte that she sent to her uncle Pierre on February 29, 1944.

On the back of the photo, in addition to the message that once again shows Charlotte’s affection for her father’s brother, one can see the Stalag IIIB stamp.

The Lamarck Center was damaged by the Allied bombardment of northern Paris on the night of April 20, 1944. From that date on, the children were housed at the De Hirsch school, which became a boarding school.

Arrest, Internment and Deportation: July – August 1944

The arrest : July 22, 1944

At dawn on July 22, 1944, on the orders of Alois Brunner, the children at the Lucien de Hirsch school were arrested. The Drancy Kommando unit, made up of one or two Germans and a few detainees who collaborated, carried out the arrest. Thanks to the witness statement of Mr. Henri Urbejtel (one of the Convoy 77 survivors, who was arrested at the same time as Charlotte) obtained by Mr. Niderman, we have some details about what happened. The children were woken up by their supervisors, who asked them to gather all their belongings to prepare to leave but did not tell them where they were going. Buses from the TCRP (the Paris Region Public Transport authority), with their open platforms at the back, were waiting for them in front of the school to take the children to Drancy.

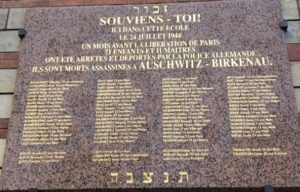

Commemorative plaque in front of the Lucien de Hirsch School

Internment in Drancy, from July 22 to 31, 1944.

On her arrival in Drancy, Charlotte was assigned the number 99 and was immediately admitted to the infirmary. This may have been due to a knee problem but the camp records do not mention the reason. It is highly likely that she stayed the whole ten days in the infirmary.

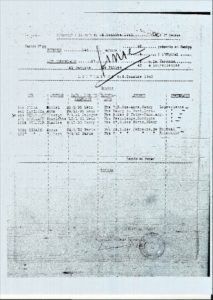

Register of arrivals at Drancy on July 22, 1944, Charlotte was sent straight to the infirmary, as were two other young girls, while most of the others were sent to the first floor at entrance 7 (7.1).

Departure for Auschwitz

In his book Mémorial des Enfants Juifs Déportés de France (Memorial to Jewish Children Deported from France), Serge Klarsfeld reports that, according to some eyewitness accounts, Charlotte Schuhmann was taken on a stretcher to the Bobigny train station on July 31, 1944 because she was suffering from knee pain. This may explain her admission to the infirmary a few days earlier when she arrived in Drancy. We have no other information about her.

If Charlotte arrived alive at Auschwitz on August 3, her poor state of health meant that she had no chance. She was probably sent immediately to the gas chambers.

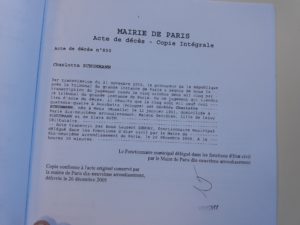

His death was not officially confirmed until 2005, when, at Mr. Schumann’s request, a death certificate dated August 5, 1944 was issued. Mr. Schumann took this step to “turn the page” i.e. as a means of closure.

Charlotte Schuhmann’s death certificate, issued in 2005.

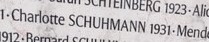

On the recently restored Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, among the names of the 76,000 Jewish deportees is that of Charlotte SCHUHMANN.

Photo taken by Mr. Robert Franck in January 2020.

We would like to thank the following for their contribution to this work:

- Mr. Henry Schumann, who kindly asked us to retrace the story of his cousin. Together with him, we got to know her better.

- Mr. Robert Frank, who came all the way from Paris to share his memories of Charlotte with us.

- Mr. Richard Niderman who, through his family research, made our task much easier

We also benefited from the support of :

- in Royan: Ms. Marie-Anne Bouchet-Roy, historian specializing in the period 1939-1945 and Ms. Isabelle Debette, director of the museum, who put us in touch with Ms. Isabelle Salvy, documentalist at the Collège Henri Dunant, who put us in touch with Mr. Robert Frank.

- in Angoulême: Ms. Sylvie Blaise-Bossuet of the Municipal Archives department and Mr. Gérard Benguigui, President of the Jewish Association of Angoulême and Charente.

- in Dordogne : Ms. Sylvie Vidal and Mr. Bernard Reviriego of the Departmental Archives department, Mr. Pascal Rolli, historian specializing in the Second World War, Mr. Stéphane Ferrier, Mayor of Festalemps and Mr. Alain Peyronnet, son of James Peyronnet.

- in Angers, Ms. Sybille Gardelle and Ms. Florence Avrillon, archivists at the Bon Pasteur community.

- in Metz, Mr. Jean-Eric Iung and Ms. Anne Belin of the Departmental Archives department, Ms. Sandrine Cocca and the staff of the Municipal Archives department.

- in Paris, Mr. Daniel Urbejtel, survivor of Convoy 77 and Mr. Serge Klarsfeld.

Students’ comments…

In March 2020, as the project was coming to an end and the Covid 19 lockdown began, the students were asked to take stock of the project. Here are some excerpts of what they wrote:

“At first I was perplexed, the idea of reconstructing the life of a young girl who died was, for me, impossible to reconstruct, the events were too long ago, the archives were too few or non-existent and, above all, no one was around to testify to a family or friendly relationship with this girl whose life story we had to reconstruct.” (Eléonore)

“This experience allowed us to learn more about Charlotte and her family. It also made us realize how much Jewish families really suffered during the war, all the pain they went through.” (Elisa)

“It also gave me the opportunity to expand my knowledge about the Second World War and the genocide.” (Léa)

“I very much enjoyed meeting Mr. Schumann and Mr. Franck who shared their knowledge with us in very moving speeches.” (Emma)

“Mr. Frank came to see us in high school, which helped us write our part of the story. It was very interesting, and seeing Mr. Frank’s emotions during his talk made his story come alive for us.” (Maxence)

“One of the most beautiful things I’ve seen this year is the emotion of Mr. Frank when he showed us the portraits of his parents.” (Tristan)

“What I particularly liked was discovering a real human story, learning details about her life. What’s more, her story was very moving!” (Léane)

“What moved me was the sweetness that this little girl conveyed through her letters. She did not deserve to die so young.” (Léna)

“I found the work on Charlotte very rewarding, very different from other lessons.” (Elisa)

“This work benefited me a lot because it allowed me to get to know all the students in the class through working together in groups.” (Nicolas)

“It was like a giant puzzle, except we didn’t have all of the pieces, so we had to do some research to find them.” (Maxence)

“I also enjoyed examining old documents that taught us more and more about Charlotte’s life and history, and also the old photos, which helped me to go back in time” (Emma)

“We even had the opportunity to search for our information ourselves, not just on the internet but in the Metz Municipal Archives.” (Mathéo)

“If I had known that in the end we would have so many documents from the archives, so much information, so many photos and so many witnesses to tell us about Charlotte’s life and if I had known the emotions I would feel during this research, I would not have questioned it all so much.” (Eléonore)

“It also gave me a better approach to working in groups and communicating with my peers. I think I was lucky, and that our class was lucky, to be part of this project because it was unique and so enriching.” (Lenny)

“This work did not simply involve writing a biography, but that of remembering all the people who were deported during the dark days of the Holocaust.” (Léa)

“The biography is like a tribute that we can pay to her for the evil that was inflicted on her.” (Juliette)

“This work made us feel more human because we not only studied the tragic life of Charlotte and her family, but we understood what their lives were like.” (Tristan)

“This keeps the memory of all the Jews, gypsies, homosexuals and political opponents murdered by the Nazis in France and Europe from disappearing.” (Maxime)

“And I also find that it makes you reflect on the world, the way some people can think, and on the injustice it causes.” (Léna)

“All of this made me realize that we’ve experienced nothing compared to them, that we have to stop complaining over nothing. There are much worse things in life and they went through them.” (Inès)

“It was a good group effort because everyone contributed and everyone was able to complete each other’s work, which leaves us with the impression that we didn’t work on one single project.” (Emma)

“I really liked working as a whole class on Charlotte’s story because it was a project where all the students got involved and gave the very best of themselves.” (Antony)

“This experience encouraged me to go to my grandparents and ask them about their past, about their childhood. I also learned that my great-grandmother was a German Jew.” (Inès)

“As part of this project, we also had the opportunity to participate in the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz extermination camp” (Mathéo)

“During this project, I greatly appreciated the group research work. On the other hand, writing up the research was less enjoyable” (Elisa)

“I don’t really have anything negative to bring up other than unfortunately there is some uncertainty about Charlotte’s death, as we don’t really know how it happened.” (Tristan)

“It’s just a shame we weren’t able to go ahead with the visit to the Shoah Memorial in Paris.” (Lenny)

Français

Français Polski

Polski

BRAVO,BRAVO et BRAVO

Je suis fier d’avoir pu contribuer à ce travail et heureux d’avoir en cours de route pu faire la connaissance d’Henry, de Robert et Nora Frank et bien sur, de ce cher monsieur Mandaroux. Admiratif devant sa qualité et ému devant l’investissement de ces élèves et de leur encadrement.

Bravo aux élèves pour ce très beau et puissant travail. Ils ont eu la chance d’être accompagnés et guidés par leur professeur d’histoire, si engagé, et de rencontrer des hommes, des témoins, exceptionnels. Cela aura été pour eux une formation humaniste incomparable.

Bravo et merci.

Très belle enquête émouvante et très bien étayée, un grand bravo aux élèves et professeurs qui ont su faire parler les archives.

On a beau savoir ce que fut l’extermination des juifs, la lecture de votre récit est profondément émouvante. Soyez persuadés que chaque étape de votre travail a concouru à cette justesse : la recherche historique exigeante, la rigueur de l’investigation, les rencontres et le recueil de témoignages, enfin l’écriture, simple et précise. Grâce à vous tous, Charlotte Schuhmann n’est plus une ombre mais une petite fille dans l’histoire. C’est une belle expérience.

Je découvre votre travail et la grande qualité de votre enquête sur la terrible histoire de la petite Charlotte et sa famille. James et Alice Peyronnet étaient mes grands parents. Je suis certain qu’ils auraient été très émus s’ils avaient pu vous lire. Merci beaucoup à vous toutes et tous, élèves, enseignants et témoins d’avoir permis à la mémoire de cette enfant de surgir de l’oubli.

Merci Monsieur Peyronnet. Nous sommes très heureux de contribuer à vous faire mieux connaître ce passé qui lie votre famille à celle de Charlotte. Les deux lettres que Lévy Schuhmann a adressées à vos grands-parents depuis Drancy sont la preuve de sa gratitude et de son affection. Votre oncle nous a dit qu’ils étaient restés très discrets sur cette triste période mais peut-être vous ont-ils confié quelques souvenirs même minimes?

bravo pour cet excellent et émouvant travail!

Laurence Klejman C77