Charles DRAÏ, 1930 – 1944

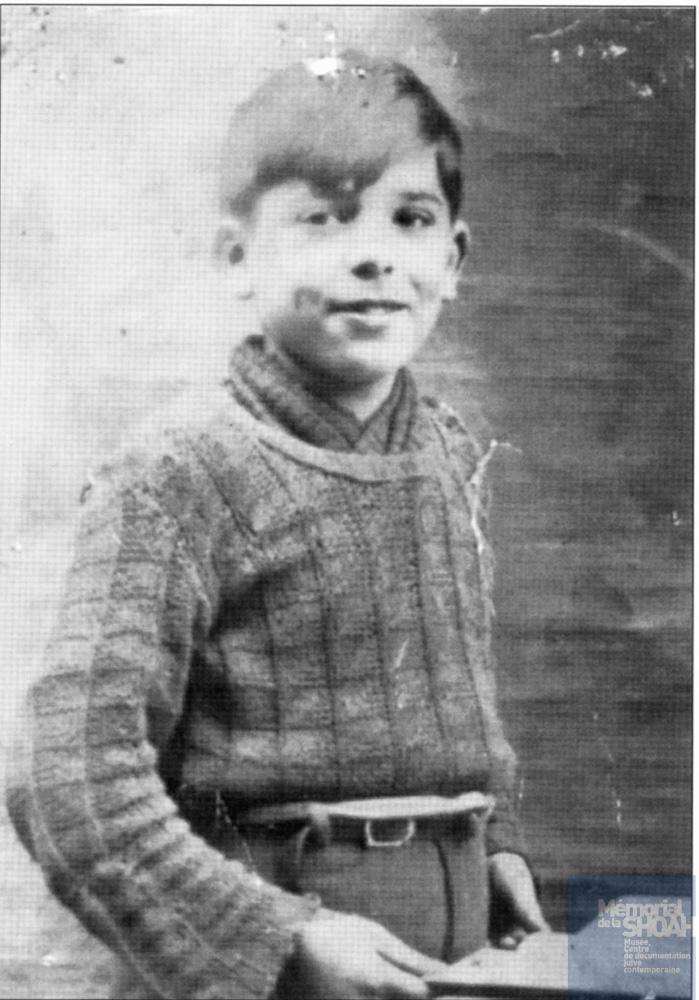

We would like to share our autobiography of Charles Draï, a Jewish boy who was deported on Convoy 77. We chose to study Charles as part of the “Convoy 77” project and because some of us in the class were drawn to the photograph that our teacher showed us, in which he looks about our age. We discovered that he was deported with some other family members, so we decided to study the whole Draï family (see the biographies of Berthe, Perlette and Marcel Draï). In order to carry out our duty of memory and to be as thorough as possible, we took our inspiration from personal accounts such as those of Ginette Kolinka, Henri Borlant and Ida Grinspan and from interviews such as that in the documentary about Marceline Loridan. However, most of the information about Charles Draï was found on the following websites: Convoy 77, Yad Vashem, the Shoah Memorial in Paris and the Paris Archives. All of this helped us to put ourselves in Charles’ shoes. He was 14 years old when he was arrested, the same as age we are now. We needed to understand the difficulties he experienced during his short life, to put ourselves in his place and to retrace his life, from his birth to his death, by being as accurate as possible and, from time to time, if the records did not answer our questions, by using our imagination.

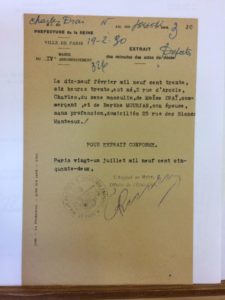

My name is Charles Draï and I was born on February 19, 1930 at 6:30 a.m. in Paris in the 4th arrondissement, at 2 rue d’Arcole. When I was born, my whole family, my father, my mother, my sister Perlette and my brother Marcel, lived at 25, rue Blancs-Manteaux in Paris.

My father Moïse was born in 1897 in Algeria, as was my mother Berthe, born on February 3, 1902. My parents were married on September 18, 1923 in Algeria before moving to France in search of a better life. We were therefore a pied-noir (blackfoot) Jewish family.

My sister Perlette was born on April 24, 1925 at 2, rue d’Arcole in Paris, as was my older brother Marcel, born on December 31, 1926.

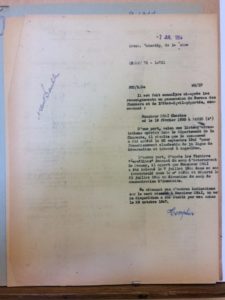

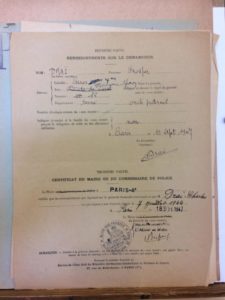

This is Charles Draï’s birth certificate, issued in 1952: it says that his mother was Berthe Mourjan and his father, Moïse Draï. Moïse was a businessman who owned a bar and his mother was a homemaker. Their address was 25, rue des Blanc-Manteaux in Paris. Charles was born on February 19, 1930 at 6:30 am at 2, rue d’Arcole.

This is a black and white photo of the Hôtel-Dieu hospital on the rue du Parvis Notre Dame in Paris, where Charles Draï was probably born.

In 1933, and again in 1938, my family grew with the arrival of my two little brothers, Roger and Richard. At the beginning of the war in 1939, nothing really changed for me. I was 9 years old and I went to the local school. My mother used to take me to the park with my little brothers. Perlette was 14, Marcel was 13, Roger was 6 and Richard was a 1-year-old baby. My father ran a bar called the “Maurice” on the ground floor of our apartment building on rue François Miron.

The Draï family at the time of the 1936 census

The 1936 census tells us about the family at rue François Miron. They were: Moïse, the head of the family, a businessman who owned a bar in the 4th district; Berthe, his wife, did not work outside the home; Perlette, a daughter; Marcel, a son; Charles, known as Charly, and Roger, a son. In 1936, Richard had not yet been born.

At 10 years old, I did not fully understand the situation, but I saw the German soldiers in the streets and the anti-Semitic posters. My mother and father spoke softly and I understood that we were in trouble. After playing soldiers for a year with my friends, we lost the war and the German soldiers invaded our streets and put up their signs. My father had to give up his bar and find work elsewhere. We could no longer go to the park with Mom because we were no longer allowed to. Marcel had to give back his wonderful bike, which I had hoped to have after him. We were not allowed to take the streetcar or the bus.

I helped my mother with the shopping by standing in line for her between 3 and 5 p.m. There were many other restrictions too: I was only allowed to go to a Jewish barbershop; I was not allowed to go to the movies; I was not allowed to go to the pool; I was not allowed to go to the movies; I was not allowed to go to the swimming pool and I was not allowed to be in a garden at home or at a friend’s house after 8pm. And, as of June 7, 1942, I had to wear a yellow star sewn onto my clothes. Richard was the only one who did not have to wear it yet, because he was only 6 years old.

A children’s playground, forbidden to Jews

A Paris street with flags of Nazi Germany

The yellow star which, as of June 7, 1942, Jews had to wear when they went out

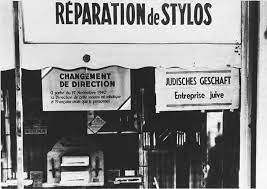

A photo of a Jewish pen repair business that had been taken over by non-Jews. This was due to the Aryanization of businesses and property; the French state stipulated that businesses be run by non-Jews, hence the change of management notice; the store was now run by French Catholics. This is what happened to Charles’ father’s bar.

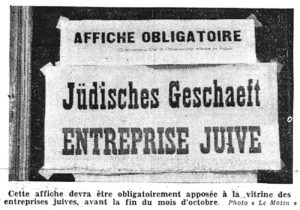

According to a decree passed in October 1940, Jewish businesses were required to display a sign saying “Entreprise juive” (“Jewish Business”) and then to be transferred to French Catholics.

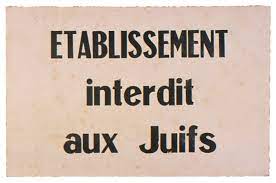

A notice stuck onto buildings forbidden to Jews, according to laws passed in 1940/1941

July 8, 1942: Jews were forbidden to walk in a square or go into a telephone booth. “Jews are forbidden to frequent certain entertainment establishments and establishments open to the public in general. Jews may only enter large retail and artisan stores, or make their purchases there, or have them made by other people, from 3 p.m. to 4 p.m.”

The Germans made it illegal for me to listen to the radio, ride a bike or go to the children’s playground. They even took away our own bar. My father’s bar was our only source of income and this left us with nothing. My father managed to find odd jobs to support us. When I walked down the street, I would hear all the time about Jews who had been kicked out of their homes and when I saw this happen, I always felt like hiding my star. I had a feeling that one day it would be my turn…

My parents decided to send Marcel and I, as well as my two little brothers, to the free zone. I left one morning, just with Marcel. I was afraid, but I hid the fear from my mother. Unfortunately, we were stopped near Angoulême as we were crossing the demarcation line. I wanted to go home but we were questioned, and even beaten, at the police department. All I wanted to do was go home and cuddle up to my Mom, but the police kept us in prison for more than 20 days. We did not confess that we were Jewish and were finally allowed to return to Paris. I would never leave the apartment again. My other brothers had managed to reach the free zone and were safe, but the atmosphere at home was no longer the same and, without them, my mother was upset and unhappy.

One day, my father did not come home. He had been arrested. My mother found out that he had been sent to Pithiviers, a camp in the countryside. She was very unhappy. Marcel and Perlette helped her but they no longer had the heart for it. We waited for him to come home, but like many of our neighbors, we had no news.

On July 7, 1944, it was my turn to be arrested, at home, in the middle of the night. It was 3:00 a.m. when police officers knocked on the door and told us to take a few things and leave. Mom, Perlette and Marcel remained calm and I tried to do the same but it was difficult; I was only 14 years old and very afraid. We were taken by bus to Drancy. There, I was separated from my mother and had to go to the men’s section with Marcel. Fortunately, I was able to stay close to my big brother, who was 18 years old so he was a big boy. The conditions are the same as in the prison in Angoulême: there were no proper facilities and very little food. We didn’t know what would happen to us and time passed very slowly. I made friends because there were many other children like me there. One evening, we were told that we had to be ready to leave the next day, July 31. We were put on buses again and we soon arrived at a railroad station. There, we were brutally crammed into cattle cars. The heat was unbearable and a lot of people were crying or sick. I was hungry and thirsty and I spent the whole day complaining to my mother, whom I was lucky enough to meet up with on the platform. She replied calmly and said that we were almost there, but I knew that was just to reassure me. During the journey, there was no privacy; I had to do the necessary in a bucket in front of everyone else. The bucket overflowed and the smell was horrible. We were all very hungry and thirsty, we were in the dark and the journey seemed to be never ending.

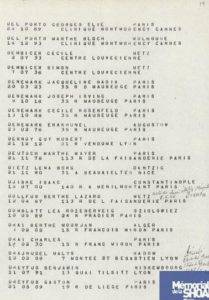

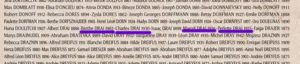

This is the list a page from the list of people deported on Convoy 77. Of the 19 names listed, 3 were children between 8 and 14 years old, 5 were young adults and the majority, 11 of the 19, were over 40, from Berthe the age of 42 to another Berthe at 77. They came from 32 countries including France, Algeria, Turkey and Germany. 1306 people were deported that day on Convoy 77, including 324 children.

Through a number survivors’ accounts, and books such as Ida Grinspan’s “J’ai pas pleuré” (“I did not cry”), we learn that people were shut in the cattle cars for several days in terrible heat, with no food or water, that a lot of people vomited during the journey and that many died.

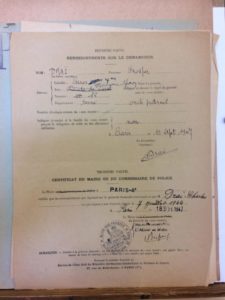

This document shows that Charles was deported to Auschwitz on July 31, 1944. It also mentions his identification number at Drancy, which was 24914

I am very afraid because I did not know where we were going. Nobody knew. Through the little ventilation space, we could not see enough of the landscape to know where we were. After several days locked in the cattle car, my brother woke me up and said that we had arrived. Some people came and made everyone get down from the cattle car, shouting at them and pushing them. The bright lights hurt my eyes after several days in the dark car. I heard orders shouted in German and I was scared of their dogs. I held my mother’s hand tightly so as not to lose her. We were all exhausted after the journey. Someone separated us into two groups and we had to form two lines. An officer then appeared in front of us. I stayed close to my mother, and the man explained that the people who were too tired to walk could ride in a truck. My mother decided that we should get into the truck because she was exhausted. My brother and my sister stayed on the platform, surrounded by other young adults. An old man in the truck tried to reassure me by telling me that would soon be able to have a rest. I think he was trying to convince himself as much as me. I smiled to my brother and sister as a way of saying goodbye. As their group headed towards the nearest building, my brother winked back at me and then we lost sight of each other. The truck dropped us off at the edge of a forest and we walked towards rest of our group. I then sat down on the ground with my mother. My mother started talking with a pregnant woman and a man in his sixties who appeared to be her father. We waited a very long time in the heat and we still had nothing to drink. I didn’t dare to leave my mother to go towards the other children so I continued to sit on the ground. After over an hour of waiting, an officer came to tell us that we were going to take a shower to cool off. We were so relieved; water at last. We were asked to take off our clothes in a locker room before going into the shower room. I was happy to finally be able to take off my jacket, which made me hot, but my mother was much less relaxed than I was because she was afraid that someone would steal our things, but an officer assured her that she would find them again after the shower because the hooks were numbered. We were all embarrassed to be naked in front of each other and I had never seen my mother naked before. We went into the showers all crowded together.

These photos from the Auschwitz album show what happened to Charles, as he got out of the cattle car, the selection and went to the edge of the forest before going into the gas chambers. These are photos of Hungarian Jews deported in May 1944, taken by German officers.

When the Jews arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazis went ahead immediately with the selection: the people were separated into two lines, the first where the people were sent into the camp to work and the second for those who were sent directly to the gas chambers. When the Jews arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, the Nazis carried out the selection: the people were separated into two lines, the first where the people were sent into the camp to work and the second for those who were sent directly to the gas chambers. Since he was too young to work in the Auschwitz concentration camp, Charles was killed in a gas chamber as soon as he arrived at the camp, as was his mother, Berthe, who was also considered unfit to work.

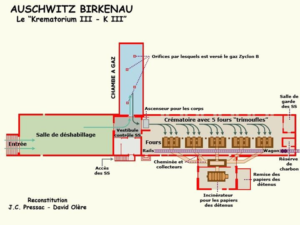

The conditions in which people died in the gas chambers were absolutely horrific. First, they were taken to a forest to wait their turn to go into the gas chamber. They were led to believe that it was a communal shower, were told to undress and were crammed into the chamber together, and then German soldiers released the gas into the hole in the ceiling of the room. The victims suffered horribly for several minutes before they died. Afterwards, Sonderkommandos had to remove their bodies and clean the room, which was covered with blood and urine, so that the next group of victims would not suspect a thing.

They also had to check to see if the dead had any jewelry or money hidden on them and if they had any gold teeth, which were valuable since they could be melted down The victims’ bodies were then burned in the crematorium.

This painting by David Olère illustrates the victims’ fatigue after the arduous journey and the selection. On the left, we can see the officer’s arm as he showed the way to go. The specter of death is already hanging over them. Their faces are haggard and it is only the warm colors that suggest that they are alive. The painting is called “Les Inaptes au travail” (“The Unfit for Work”).

This drawing shows the layout of Krematorium III: It shows the changing room, the gas chamber and the line of crematorium ovens. It was drawn by David Olère, who was a Sonderkommando in the camp. The Sonderkommando were Jewish deportees who were forced to do the menial tasks in the camp. They were kept separate from the other prisoners.

Charles was officially recorded as having died on August 5, 1944, in Auschwitz, Poland, according to the 1947 law for any “non-returned” Jewish person over the age of 55 or under the age of 14. Charles did not fit into this category, and neither did his mother, yet under French law, they were considered to have died on August 5, 1944.

The very existence of this law is proof that a large number of people were known not to have returned from the camps: it states if there was no further news of a person after the war, they were deemed to have died five days after the departure of the convoy on which they were deported. This was thus official recognition of the extermination that took place.

It was Prosper Draï, Charles’ uncle, who requested information about the death of his nephew and sister-in-law, and then handed over the task to Perlette, Charles’ sister. They began the process of having him recognized as a political deportee and a victim of war, and they received a sum of money from the French government to compensate them for their loss. Charles was officially recognized as having been a political deportee in 1955.

Charles’ remaining family lost their father, Moïse, and their mother, Berthe Mourjan Draï, who was declared dead on August 5, 1944, as was Charles. However, we note that the names of some other people with the surname Draï are inscribed on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris; perhaps they were relations. The other children, Perlette, Marcel, Richard and Roger, survived, the latter two having been kept hidden during the war. After having been repatriated, Perlette and Marcel met up in their apartment at 15, rue François Miron and later took over their father’s bar, the “Maurice”. A few days after their return, they met up with their two little brothers in Paris, together with their uncle, Prosper Draï, who had been taking care of them.

The names of Berthe, Charles, Perlette and Marcel on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris

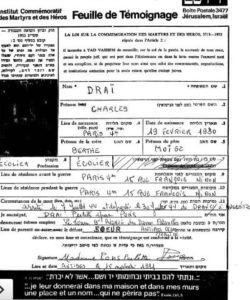

In 1991, in order to leave a lasting trace of her family, Perlette filled out a Page of Testimony online for each deported family member. This is the page for Charles.

The purpose of these pages is to ensure that people will never be forgotten, as it says on the form: “And I shall give them in My house and within My walls a Memorial and a name… that shall not be cut off” Isaiah 56:5. This is also our reason for participating in the Convoy 77 project.

We have pieced together an incomplete family tree of the Draï family. We were unable to find Roger and Richard, or Marcel. We asked the Shoah Memorial for the contact information of Maurice Pons, Berthe’s grandson, but to date we have no further news.

Orens, Artharsha, Kenzo, Kylian, Yani, Margot, Mathis

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Merci pour cette autobiographie. Je mapelle lea je suis la petite fille de roger, le jeune frere de charles. Mon grand pere est decedee de la maladie il y a quelques annees il a eu deux enfants dont mon pere et sa soeur. Mes parents et ma famille respective vivons en israel.

Relire son histoire grace a vous, nous a tous bouleversé. Nous vous remercions davoir honorer leurs memoires a travert ce recit.