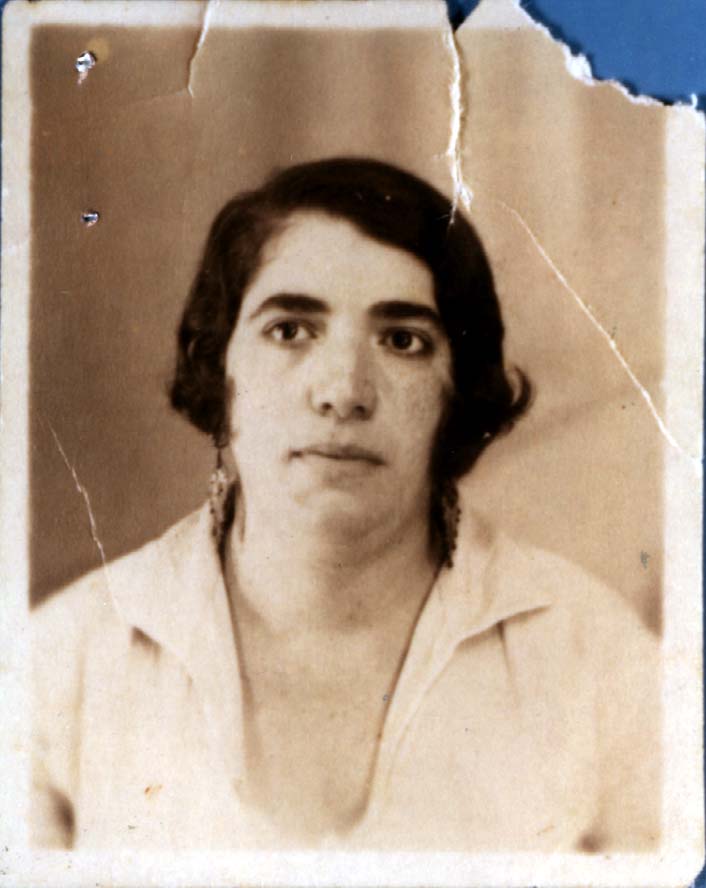

Berthe DRAÏ, née MOURJAN, 1901 – 1944

The following text is a fictional autobiography written by a group of students from the Les Blés d’Or junior high school in Bailly-Romainvilliers, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. We wrote it to shed new light on the life of Berthe Draï, a Jewish woman deported with her family on Convoy 77. It is based on documents provided by the Convoy 77 association, research carried out on the Shoah Memorial, Yad Vashem and other websites, and on the testimonies of other deportees (see also the biographies of Marcel, Perlette and Charles Draï).

Dear Readers,

I am going to tell you about my life.

First of all, I would like to make it clear that I am going to be totally honest with you. My name is Berthe Mourjan, I was born on February 3, 1901 in a city in the north of Algeria called Algiers. I belonged to the Jewish religion because both of my parents were Jewish. I was born in my parents’ house, where I then lived with my family.

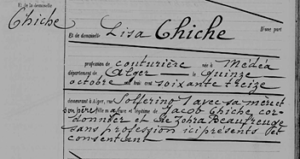

My mother’s name was Lisa Chiche. She was born on October 15, 1873 in Medea in Algeria. Until she was 23 years old, she lived with my maternal grandparents, Jacob Chiche, who was a shoemaker and Zohra Beaufreuge, a housewife. Chaloum Mourjan, my father, was born on October 28, 1873 in Collo, Algeria. He also lived with his mother, Ester Qualid, until he was 23. She was a widow, so I never had the chance to meet my paternal grandfather, Joseph Mourjan.

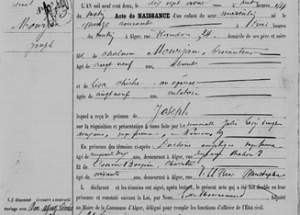

My parents were married on February 16, 1896. Shortly afterwards, they moved in together and lived on rue Rauclon in Algiers. I was the youngest girl in the family. I had an older sister, Jeanne, born on March 25, 1899 and a younger brother, Joseph, born on April 17, 1902.

My mother, who was not working when I was born, became a seamstress after Joseph was born, in order to increase the family income. As for my father, he was a second-hand goods and antiques dealer.

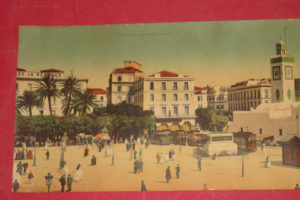

Postcard of the government square in Algiers in around 1940

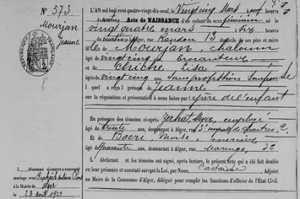

Berthe’s parents’ marriage certificate. It mentions their professions, address and dates and places of birth

The birth certificates of Jeanne, Berthe’s older sister, and her younger brother, Joseph

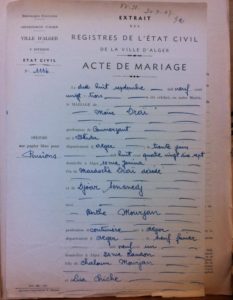

On Berthe’s marriage certificate, we see that Moïse was a trader and she a seamstress

I met Moïse Draï and we got married in 1923 in Algiers. We chose to move to Paris, in France, in the hope of a better life. Our children were all born in Paris: Perlette in 1925, Marcel in 1926, Charles in 1930, Roger in 1933 and Richard in 1938. Moïse bought a bar at 15, rue François Miron and we lived in an apartment above it. I was a housewife.

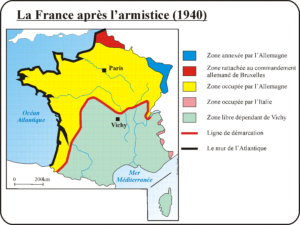

In September 1939, when the Second World War began, it did not affect my family and I very much. However, in the spring of 1940, with the defeat of France, things suddenly changed for us. We lived in Paris, in the part of France that was occupied by the German army, and this coexistence soon became tiresome.

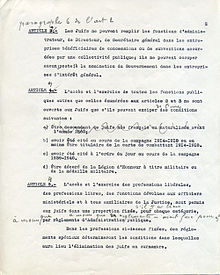

In October 1940, the new Vichy government, led by Marshal Pétain, issue a decree concerning the status of the Jews: action was taken against us immediately and we were no longer treated like ordinary French folk. One law forbade us from working in many professions. The immediate consequence for us was that we could no longer run our own bar. They called this the Aryanization of assets: only non-Jewish French people were allowed to run businesses.

There was a lot of discussion about Jews in the press and on the streets, and we didn’t feel as safe as we had in the past.

In June 1940, France was defeated by Germany. Marshal Pétain was appointed Commander-in-Chief and signed an armistice on June 22, 1940. The north of France, with the loss of Alsace-Moselle, was occupied by the Germans. It was ruled by Marshal Pétain and his government from the so-called “Free Zone”.

Map of France in 1940, after the signature of the armistice

During the German occupation, the streets in the capital changed significantly. Flags of the Third Reich were scattered all over Paris, as seen here on rue de Rivoli. The hotels were then commandeered by the occupying forces.

The decree that forbade Jews from working in various professions

This document, which is the official record of Berthe Draï’s death, lists her most recent address as 15 rue François Miron, in the 4th district of Paris.

Posters appeared everywhere, portraying us as thieves and murderers, stigmatizing us and pointing the finger at us. It became more and more difficult for me to feed my family because in addition to the shortages and rationing tickets, we were forbidden to go to the stores at the same time as non-Jews. I couldn’t even take the kids to the park because they too were forbidden to Jews. We had become undesirables, not to be seen or heard. Some of our neighbors disappeared in the spring of 1941, when the police came to arrest them, and we never heard from them again. Some people said that they had been taken to work in Germany against their will. I was very wary and worried. Moïse and I decided to send the boys to the Free Zone to avoid the round-ups. We decided to send them in two groups, Marcel and Charles, the older ones, on their own and the two younger ones, Roger and Richard, with their uncle Prosper. We were surprised to see the two older ones come home again just a short while after they left. They explained that unfortunately they had been arrested at the demarcation line and had spent time in prison in Angoulême, where they were interrogated and beaten. This was in September 1942. At least they had escaped the worst! We felt that perhaps we had made a mistake in sending them off on their own, and I hoped that everything would turn out better for the younger two.

As from 1942, we had been obliged to sew a yellow star on our clothing, which made us even more conspicuous when we were out in public. If we didn’t wear a star, we ran the risk of being arrested. We therefore wore it to comply with the rules, but it was very humiliating.

Worse came to worst in 1943, when Moïse was arrested. All we knew was that he was transferred to the Pithiviers camp, but we never heard anything more. I was sure he was dead, because what use would he be in a labor camp at the age of 46? Now, at the age of 42, I was left alone to take care of my family. I was desperate and very worried. Perlette and Marcel helped me as best they could and I tried to put on a brave face in front of them, but my morale was at its lowest, especially since many of our friends had disappeared from the neighborhood and it was becoming hard to help each other out.

In the spring of 1944, when we heard that the Allies had landed in Normandy, we regained hope, and we began to look forward to the Liberation.

However, in the middle of the night, at 3 a.m., the police knocked on our door. On July 7, Charles, Marcel, Perlette and I were all arrested. Since the miracle had not happened, I thought that perhaps we were going to meet up with Moïse, wherever he was. We had just enough time to gather a few things and then we had to leave and follow the police officers.

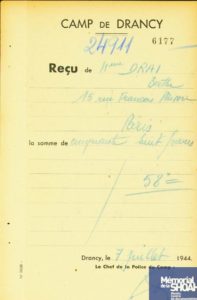

When Berthe arrived at the Drancy transit camp, she had to hand over the 58 French francs she had with her, for which she was given a receipt. This sum reflects her limited means, given that people usually arrived with larger sums of money. Berthe was sent to Drancy on the same day that she was arrested, unlike many other people, who were either interrogated or sent to prison. She and her children stayed in Drancy from July 7 to July 31, when they were all deported on Convoy 77. On the list of deportees that day, only Charles and Berthe are included, even though all four family members were deported together.

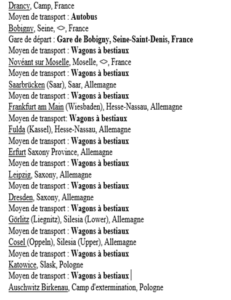

We arrived at Drancy, a camp with a bad reputation. Had Moïse also spent time there, I wondered. Were we going to work in Germany, I asked myself? I was separated from the boys because we had to go to a women’s dormitory. Marcel went away with his brother Charles and I hoped that they would be all right. To keep myself busy, I helped out in the kitchen; the vegetable peelings added to our food ration. I also tried to catch a glimpse of the boys. I crossed paths with Perlette, who had made friends with some roommates. The living conditions were very basic. We slept with no mattresses or covers, as if we were in a prison, and the guards saw us as mere numbers. A lot of children arrived that month, brought in from orphanages in and around Paris. They were too young to work, so how were we still supposed to believe that we were all going to work in the East? My heart was breaking; Marcel and Perlette would be able to manage but what about my little Charles? After 24 days in Drancy, we were taken by bus with our meager belongings, but without our money, to Bobigny railroad station.

On the platform at Bobigny, we were pushed roughly into cattle cars, regardless of our age or any difficulties we might have. We were all crammed in together and when the doors were closed and locked, we found ourselves in the dark. Some people were in a real panic, especially the children, who we had to reassure as best we could. One single bucket made it clear that no breaks were planned and that we were going to find ourselves in appalling, unhygienic conditions with no privacy. The smell quickly became unbearable and there was no air. How long was this journey going to last?

Obviously, I was scared! I had no idea where we were headed. I had imagined many things but never anything as awful as this.

When we arrived, the doors opened suddenly and we were blinded by the glare of the lights. Our eyes were no longer used to the light after several days spent in darkness in the cattle car. Once we were down on the platform, it was all a mad rush; people were lost and being pushed about by German officers, children were crying and screaming, scared by the barking dogs and orders shouted in German. We were separated ruthlessly into two groups and asked to leave our things on the platform. I didn’t know exactly what this was all about. I thought we had come to work, but I didn’t know what kind of work.

All I could see were two lines, one with mainly men, while in mine there were more women and children. Men dressed in striped pajamas, some of whom spoke French, were there to show us where to go.

I walked with the rest of my group along the railroad track beside the platform until we came to a forest. We were so tired, and it was a very long way!

We waited there until we were told to go to the changing rooms to freshen up after the journey. I was glad, because after the long train ride, where we were all packed together and there was only one bucket to relieve ourselves, I felt really dirty. In the locker room, we had to get undressed, despite the embarrassment of being naked and worrying about not being able to find our things again. Thinking we were about to get washed, we went into what we thought was the shower, but then panic set in when we saw the naked men approaching.

It was in fact a gas chamber. We have decided to portray Berthe’s death through two collections of photos: those taken by the Germans of a convoy of Hungarian Jews in May 1944 and the four “stolen” photos taken by some Sonderkommando from the Birkenau camp. Members of an internal resistance movement, these men risked their lives to take the photos in order to bear witness to the genocide. This explains the poor framing of the photos.

They show what Berthe must have experienced: waiting in the birch forest (Birkenau in Polish), getting undressed, and also the incineration of the bodies outside when there were too many to burn in the crematorium ovens.

This picture shows the selection, carried out as the deportees got off the train, with the men on the right, the women and children on the left, the Sonderkommando in striped pajamas and the German officers, with the entrance gate to Birkenau in the distance (Auschwitz II)

These photos show groups of women and children on the edge of the woods, waiting for instructions. In the background are the buildings of the camp behind a barbed-wire fence.

These blurred photos, taken in secret, show a group of women, naked or getting undressed.

In these snapshots, we see the Sonderkommando incinerating the bodies taken out of the gas chamber. They were cremated outside when there were too many to burn in the crematorium ovens.

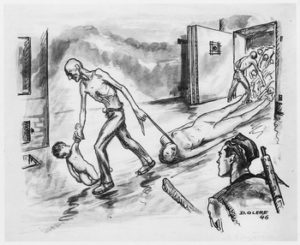

This drawing, by David Olère, represents the removal of the bodies from the gas chamber by the Sonderkommando, who dragged the dead to the crematoriums. David himself was deported to Auschwitz. A former Sonderkommando, he testified both in the camp and after the liberation. Sonderkommando were Jewish prisoners who were forced to do the dirty work of the genocide and kept in a separate area of the camp. They wore a distinctive uniform; the infamous striped pajamas.

This photo shows the gas chamber in Auschwitz (I). Berthe, however, was killed in Birkenau in a larger gas chamber that has since been demolished.

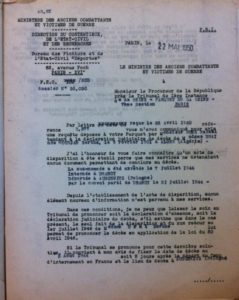

Having “disappeared” in Birkenau, Charles and Berthe were officially declared to have died on August 5, 1944, according to a French law passed in 1947. This law stipulated that anyone under 14 or over 55 years of age who did not return from the camps was deemed to have died five days after the departure of their convoy. Although Berthe and Charles did not fall into either of these two categories, since there was no news of them after the war, they were officially declared dead. Whether Berthe travelled with her children on the convoy, or whether Charlies died alongside her, is not known.

Berthe’s older two children, Marcel and Perlette, survived and returned to Paris, where they took over their father’s old bar, the “Bar Maurice”. After it reopened, a customer who had survived the deportation went in almost every day to say how sorry he was, and to offer Marcel and Perlette his condolences. They always thanked him, not knowing what to say, according to Perlette’s account in a Jewish newspaper (see Perlette’s biography).

To celebrate Shabbat (the Jewish weekly celebration, which runs from Friday evening to Saturday evening), Perlette resumed her father’s custom of cooking a traditional Algerian meal called Barbouche. This was a couscous-based dish that her father always wanted to share with the other Jews in the neighborhood. In doing this, Perlette tried to recreate the Blackfoot Jewish atmosphere of her childhood, but it was not, and never will be, quite the same again.

This is a photo of “Bar Maurice”, taken in 1946. Perlette and her husband are on the left of the picture, with Marcel and a regular customer.

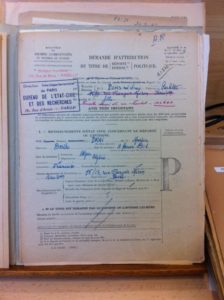

Berthe’s children undertook the necessary paperwork to have their mother, Charles and Moïse recognized as having died as victims of war and then as political deportees. Berthe was finally acknowledged as having been a political deportee in 1952. Perlette’s signature can be seen at the top of this page of the file.

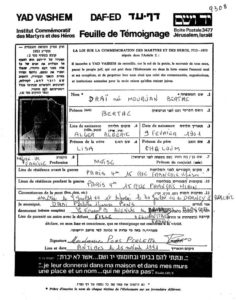

Today, Berthe’s name is inscribed on the wall of names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, and Perlette filled out a testimonial form at Yad Vashem (see below)

This Page of Testimony form is available on the Yad Vashem website or at the entrance of the Memorial. It allows people to leave a record of a person who disappeared during the Second World War in the context of the Holocaust. Each form bears witness to a life erased from history.

We have pieced together an incomplete family tree of the Draï family. We were unable to find Roger and Richard, or Marcel. We asked the Shoah Memorial for the contact information of Maurice Pons, Berthe’s grandson, but to date we have no further news.

Diane, Laura, Elisa and Luka.

Français

Français Polski

Polski