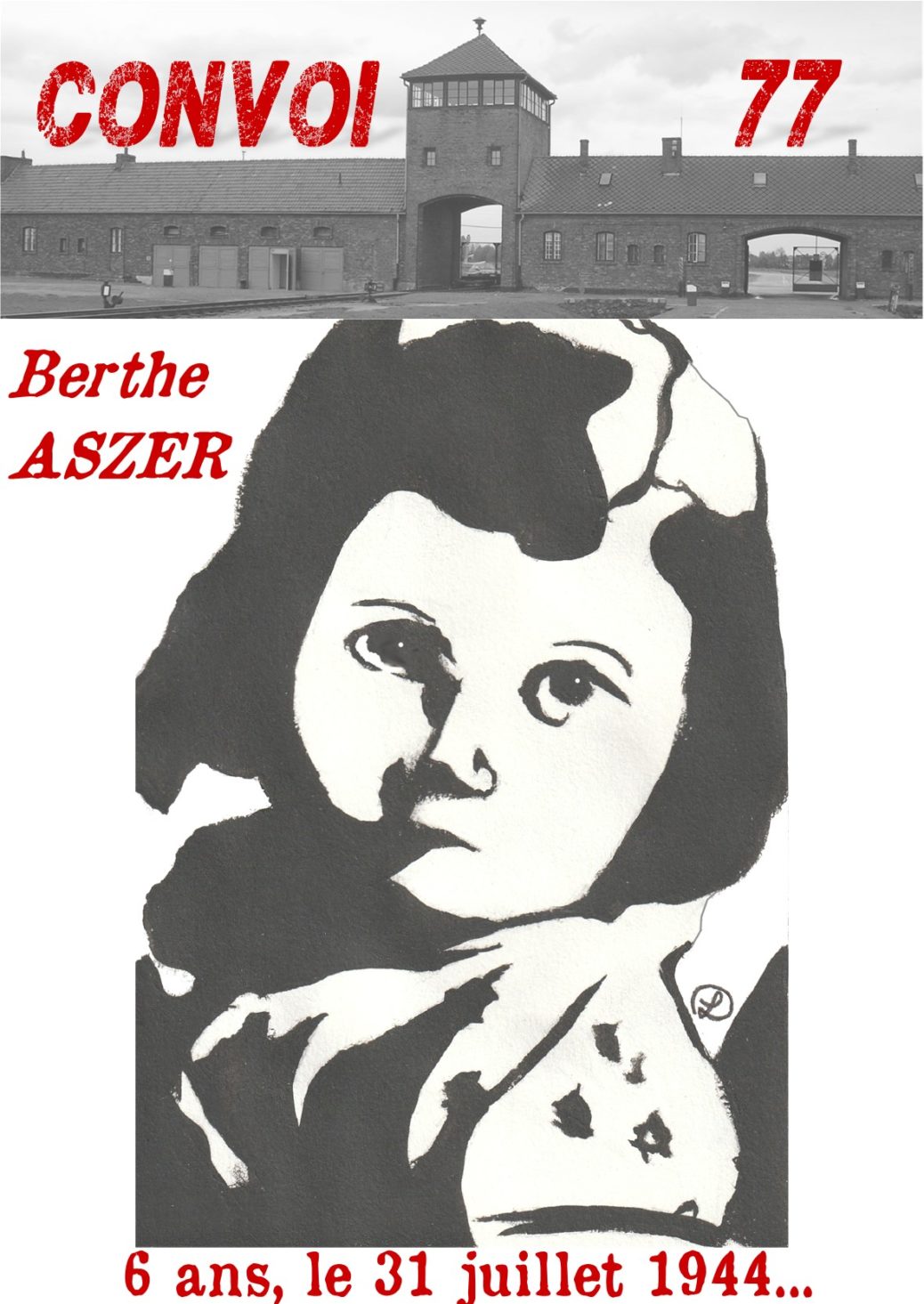

Berthe ASZER

Editor’s note

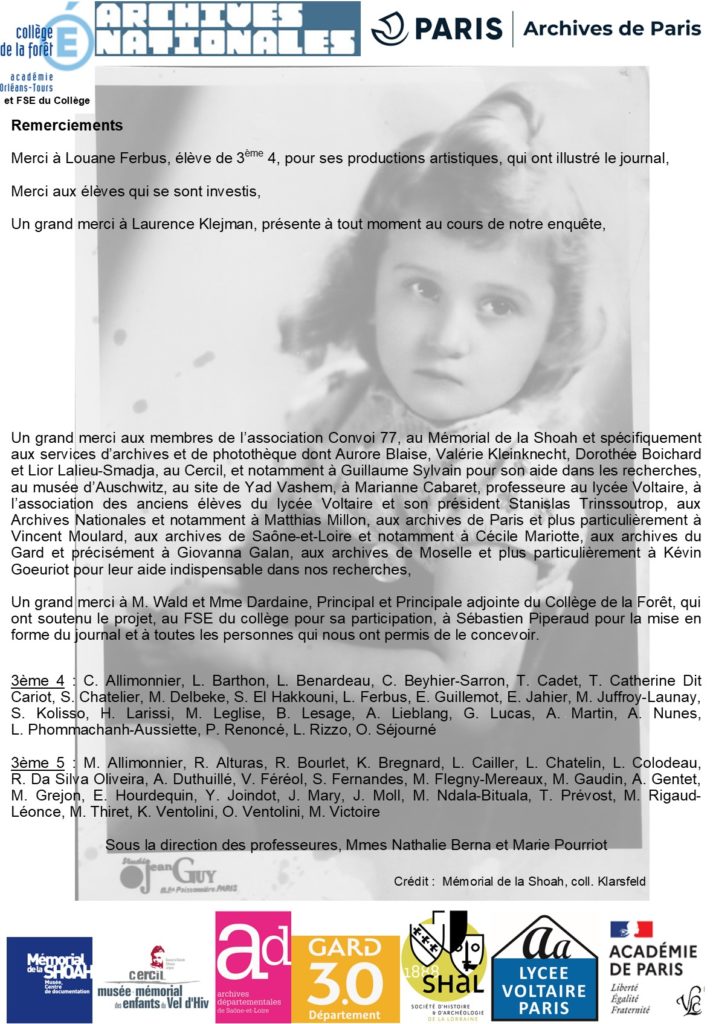

Two classes of 9th grade students, undeterred by the pandemic, set off on a historical exploration in 2020 at the start of a rather unusual school year. Under the guidance of two very committed teachers, Ms. Nathalie Berna and Ms. Marie Pourriot, the 51 students took their first steps as investigators to retrace the lives of people who were deported on Convoy 77: the young Berthe Aszer and a man called Simon Stanger. These two people had nothing in common except for being listed as “Jews” according to French and German laws in force in the summer of 1944, when their paths crossed.

Berthe Aszer was just 6 years old, and the students who undertook to write the biography of this young Holocaust victim soon drew a parallel with their own lives. It was the age at which they began second grade, which did not seem so long ago. They realized that she never had the opportunity to be as lucky as they were or to go to high school. When they first looked through the records available on the young deportee, they were immediately struck by the fact that while Berthe was murdered in Auschwitz on August 5, 1944, her official French death certificate was only issued on May 30, 2013. Why did it take almost seventy years for Berthe’s fate to be recognized once and for all by her country as a victim of the Holocaust? Or for it to be officially acknowledged that she had “Died for France”?

The students followed in the footsteps of a family of Polish Jews who emigrated to Metz, in France, where Berthe was born, and then moved to Paris when the war broke out and the eastern border regions were taken over by the Reich.

Meanwhile, the students also set about reconstructing the life of Simon Stanger. A young Polish Jew, who came to live in France, trusting in the French Republic, Simon was one of the first people, mainly men, to be affected by the anti-Jewish laws enacted by Philippe Pétain’s government. His story is that of a man who tried everything to survive the barbarity, escaping several times from French internment camps, and managing to survive and return from the extermination camps in Poland, in bad shape but ready to rebuild his life, which, as we will see, he did.

The students discovered “from the inside” what the anti-Jewish policies and round-ups really meant for people of all ages. This included the Vel d’Hiv round-up, during which Berthe and her parents were arrested, as well as the so-called “Green Ticket” roundup in May 1941, to which foreign Jews living in Paris, many of whom had volunteered to fight against the German troops, were summoned to go, and which Simon Stanger confidently attended. Before being sent to Drancy camp and being deported together, Berthe and Simon had already experienced, at different times, the camps in the Loiret department of France, the sad antechambers of the death camps, as were Drancy and Compiègne in particular.

The fruits of the students’ research are recorded in an illustrated journal where archived material and photos are used to enhance a vibrant and historically accurate narrative that provides readers with a body of knowledge that goes well beyond the biographies of Berthe and Simon.

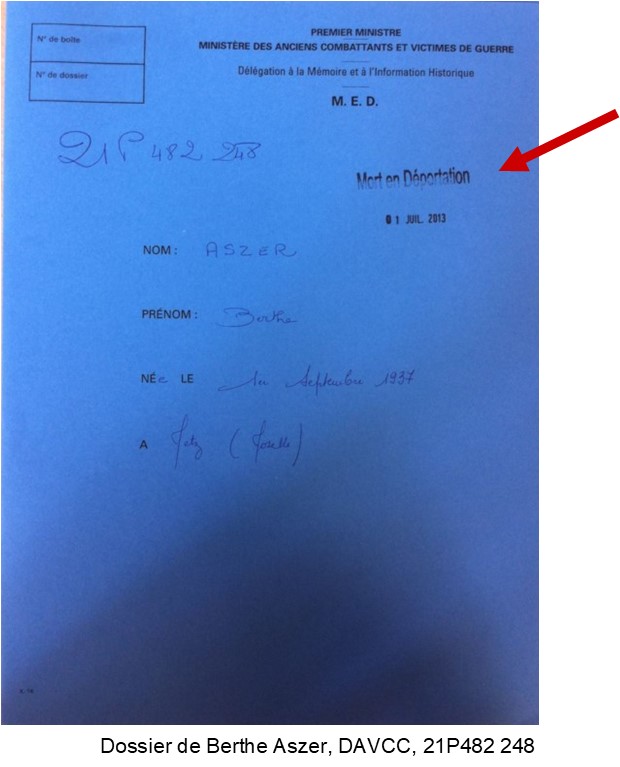

Their investigations were meticulous and thorough. As a historian, I commend the work they have accomplished, despite the difficulties caused by public health crisis, by searching for and finding documents in the departmental and national archives, in books, at the Shoah Memorial in Paris and at Yad Vashem, in particular. They have thus greatly increased the limited information provided by the records held in Caen by the DAVCC (Division des Archives de Victimes des Conflits Contemporains au Service Historique de la Défense, the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service).

Their biographies, along with some of the photos and drawings by two of the students, will be posted on the Convoy 77 website. This historical project will be of use to everyone, but it is not hard to imagine that on a personal level, each student will have gained experience that will strengthen his or her sense of citizenship, and perhaps also a taste for history.

L. Klejman, historian, convoi 77

The beginning of our investigation

Introduction to the project

Our teachers, Ms. Berna and Ms. Pourriot, introduced us to the project in October 2020.

We were at the start of our 9th grade year, and not particularly enthusiastic about the project. That day, we learned that we were going to investigate a 6 1/2-year-old child, a victim of the Holocaust, who had been murdered.

The story intrigued and challenged us even more when we discovered the first archived record about this little girl called Berthe.

When we looked closely at the records, we noticed that the official death certificate is dated May 30, 2013.

We ourselves were 6 years old in 2013 and we were just starting elementary school.

Little by little, we became aware that we were becoming involved in the life of this forgotten little girl.

Her death certificate was only issued in 2013, yet she had died in August 1944.

How come, after seventy years, she was finally acknowledged as “Morte en deportation”, i.e. to have “Died during deportation”?

What is “Died during deportation”?

What does this status mean? Who is entitled to it?

It was the French “law n°85-258 of May 15, 1985 which introduced the inscription “Died during deportation”. It is added to the death certificate of any person of French nationality, or resident in France or in a country previously under French sovereignty, protectorate or guardianship, who, having been transferred to a place recognized as a deportation destination, died there.”

Why did Berthe Aszer, who was born in France, have to wait nearly seventy years to have this inscription added to her death certificate?

We began our investigation.

Metz, in the years 1920-1930

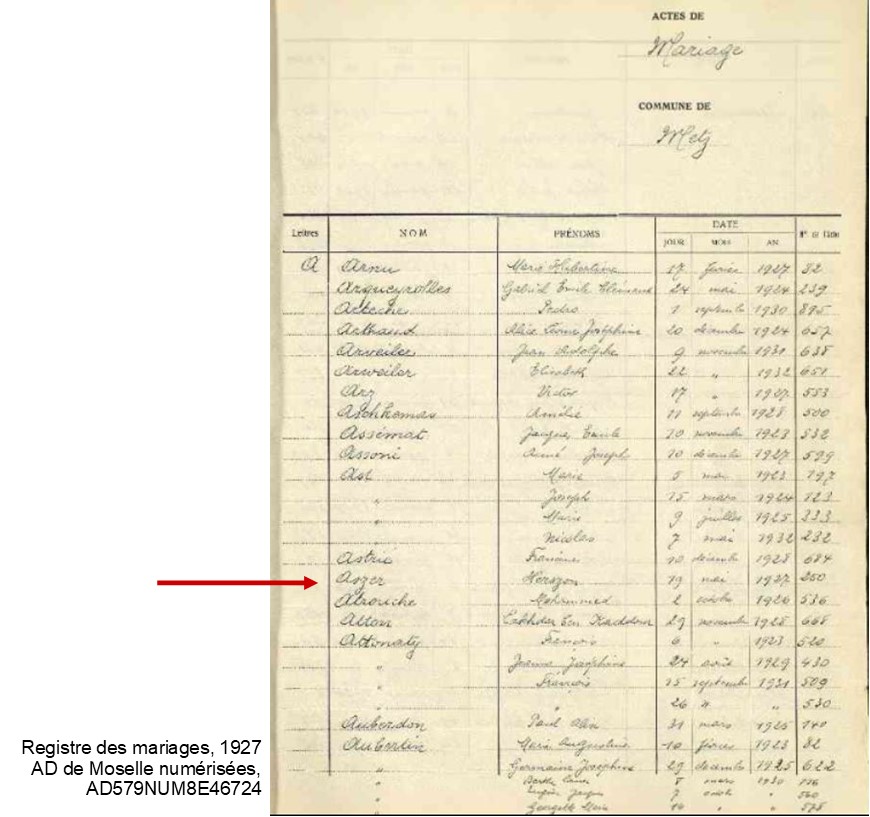

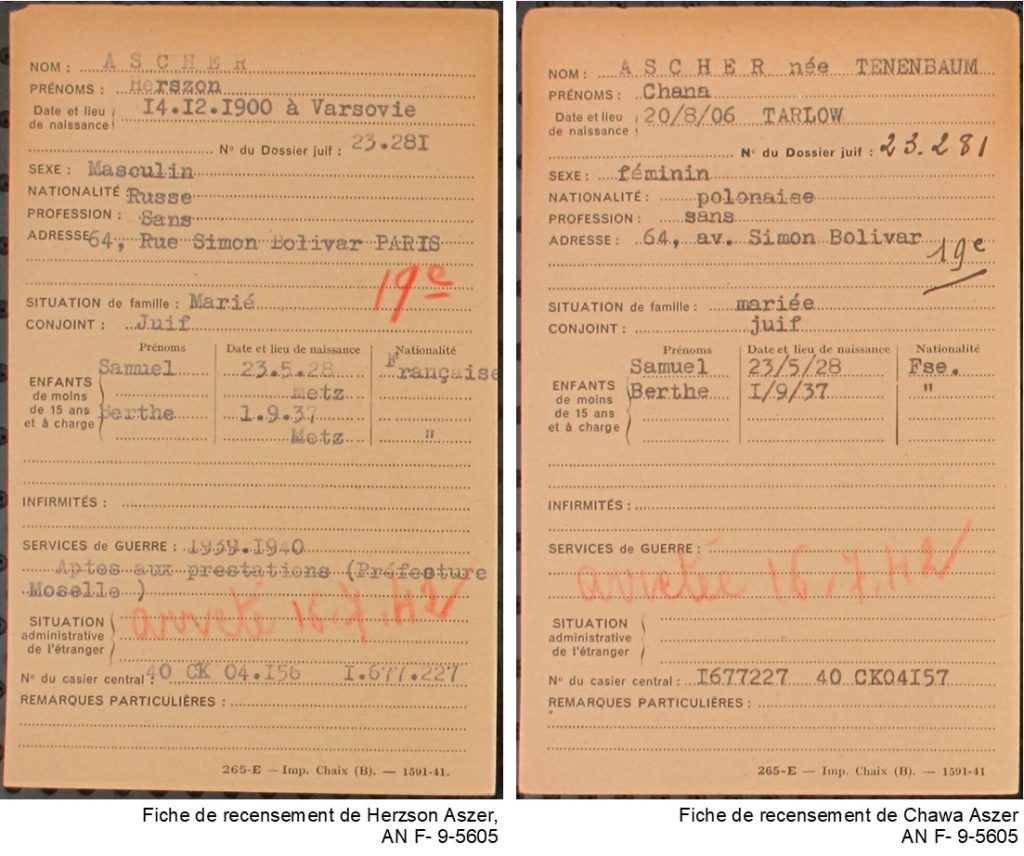

Herzson Aszer, who was born on December 14, 1900, in Warsaw, Poland, and Chawa Aszer, née Tenenbaum on August 20, 1906, in Tarlow, Poland, were married in Metz on May 19, 1927.

Herzson was a tradesman and Chawa was not working at the time.

We know, thanks to the Moselle departmental archives, from a document in which the members of the Kenesseth Israel association are listed, that the maternal grandparents, Isek and Cipa Tenenbaum, arrived in Metz in 1924, after passing through Varangéville, in Meurthe-et-Moselle (reference 304M112).

Isek Tenenbaum was born in Zavichost, Poland, on November 25, 1872.

Carle-Cipa (whose name was later changed to the French version, Cécile) Tenenbaum, née Libermann, was born on March 17, 1875, in Tarlow, Poland.

Isek was in possession of a receipt of application for a foreigner’s identity card. The register states that they had three children.

They set up home at 1 bis, rue de la Grande Armée, in Metz, where they also ran a men’s clothing business.

Did Berthe’s father work in the family store? We don’t know. It seems that the Aszer family kept a low profile during their time in Metz.

Samuel Aszer, known as Samy, was born in Metz on May 23, 1928.

The Aszer family lived at 9 rue Ausone, in Metz, about a mile and a half away from the grandparents.

1927 marriage register. Source: Moselle departmental archives, record n° AD579NUM8E46724

Metz is a city in the Moselle department, which is in the Lorraine region of France.

It is one of the cities that fell victim to the Franco-German war of 1870 and was thus annexed to Germany from 1870 to 1918.

After the armistice in 1918, the Moselle department became French again.

This reattachment to France caused some controversy. Some people were in favor of the idea of being French while others were opposed and wanted Moselle to revert to Germany.

Due to the incorporation into France, German citizens were expelled from Metz in 1918 and 1919, while Polish newcomers settled there after the breakup of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Thanks to American intervention, many Germans who had been expelled were able to return from 1920 onwards, but at the beginning of the 1920s, the Metz economy suffered greatly.

In 1920, the German-speaking population accounted for only 30% of the population of Metz. It was mainly made up of workers and small tradesmen.

This sector of the population maintained a hostile attitude towards France.

In those days, the headquarters of the Est region of France was located in Metz. As a result, the city was very busy with military personnel who visited the more than three hundred cafés in the town. It was nicknamed the “Paris of the East”.

The history of the city of Metz is important because the population became bilingual after 48 years of annexation, and German culture continued to influence the way of life of the local people.

The majority of the residents of Metz therefore had a dual Franco-German culture that was important in the run-up to the Second World War.

Finally, it should be noted that in 1939, one ninth of the population of Metz was Jewish, which represented around 10,000 people.

As a result of France’s defeat, Metz was evacuated in May 1940 and declared an “open city” on June 14, 1940.

Three days later, on June 17, 1940, at 5 p.m. to be exact, a mobile patrol of the 379th Regiment rolled into the deserted town. An hour later, the swastika flag was raised over the town hall.

From the outset, despite the agreements signed between the two countries, the Nazi regime immediately began annexing Metz, as it did the rest of the Moselle region.

In August 1940, the Moselle department, which was by now annexed to the Reich, was declared “Judenfrei”, i.e. free of Jews.

We therefore concluded that if the Aszers were in Paris in 1940, they must have planned their departure in advance.

The municipal administration was taken over by the Nazis, who replaced most of the French officials. Streets were renamed, store signs were removed and replaced with German ones, and most of the statues were taken down.

Metz was thus occupied again from 1940 to 1944. It was liberated between November 19 and 21, 1944 by the American army.

M. Gaudin

September 1 1937, in Belle-Isle hospital

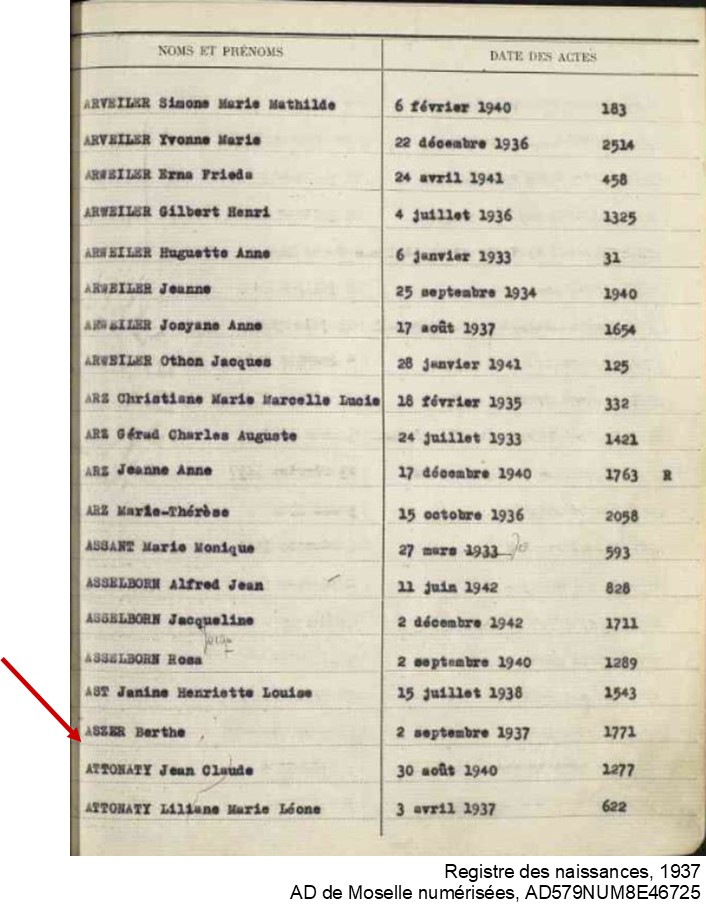

Berthe, known as “little Betty”, was born at 3.15 p.m. on September 1, 1937 at the Belle Isle Hospital in Metz.

The Belle-Isle hospital

The Belle Isle Hospital was founded in 1874 by the Deaconess Sisters of Stuttgart, otherwise known as the “Sœurs de Marthe”, “The Sisters of Martha”. It was originally a Protestant nursing home for single women, children and the elderly, and called the Mathildenstift hospital.

Count Arnim von Boïtzeburg, the then president of Lorraine, financed a large part of the construction.

In 1884, after ten years of activity, the premises proved to be too small and the hospital was relocated to rue Belle-Isle, on the banks of the Moselle.

When this new facility opened, it was announced that patients of all faiths would be admitted.

In 1919, which marked the end of the German annexation, the Mathildenstift hospital changed its name to Hôpital des Remparts Belle-Isle, and then to Hôpital Belle-Isle, the Belle-Isle Hospital.

In 1945, as a result of the damage caused during the Second World War, the hospital was rebuilt and re-equipped.

In 1963, an ambitious real estate project increased its capacity with the construction of three new buildings.

In 2006, the hospital celebrated the 120th anniversary of the laying of the foundation stone on rue Belle-Isle.

E. Hourdequin

L. Barthon

1937 birth register. Source: Moselle departmental archives service.

Paris, 1940…

A letter from Berthe’s grandfather, Isek Tennenbaum, dated late July 1942, mentions that Herzson, his wife and two children had left Metz. It is kept at the Shoah Memorial in Paris.

As for the maternal grandparents, they moved to Nîmes in March 1941. They lived at 5 bis rue d’Albenas with their youngest daughter, Sabine, one of Berthe’s aunts.

We discovered, through records in the Gard departmental archives (1W139), that the Tenenbaums were a French Jewish family. Isek and Carle-Cipa Tenenbaum had 6 children.

From the Paris archives we found an application to enroll Samuel at the Lycée Rollin, a high school in the 9th district of Paris, for the 1940-1941 school year. The class is listed as 8th grade B1 (reference 3769W90).

Herzson gave their address as 125, Boulevard Richard Lenoir, in the 11th district of Paris.

We then noticed that Samuel’s previous school was in Les Sables d’Olonne, in the Vendée department on the west coast of France. Did the Aszer family, when they left Metz, move to the Vendée for a while? We do not know. The Vendée departmental archives service can find no trace of Samuel in any of the schools there.

The Rollin High School register for the 1940-1941 school year reveals that Samuel, known as Samy, was registered as a day boarder. He chose English and Spanish as his foreign languages, and was in 8th grade, class B1.

We also see that their first address in Paris, which was 125, boulevard Richard Lenoir, has been crossed out and replaced by their last known address: 64, avenue Simon Bolivar, in the 14th district.

In his school report, his teacher mentioned his disrespectful attitude and poor results. He was punished following a meeting of the school’s disciplinary council and was subsequently expelled (reference 3769W56).

Following the German order of September 27, 1940, the Aszer family took part in the census of the Jews. The French police department issued the following notice in the press and on posters:

“Jewish nationals will, therefore, have to report to the police departments of the districts or precincts where they live, bringing with them proof of identity.”

The census took place from October 3 – 19, 1940.

Paris in the years 1930-1940

The beginning of the 1930s was a time of growing economic crisis following the stock market crash of 1929, along with increasing extremism, international friction, xenophobia and anti-Semitism, and subsequently the outbreak of the Second World War.

In 1934, the Stavisky affair triggered a French political and economic crisis. The death of the swindler Alexandre Stavisky in mysterious circumstances only served to intensify the already widespread anti-Semitism in France.

In 1935, the Joliot-Curies won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of induced radioactivity.

After the election of the Front Populaire (Popular Front) and a wave of strikes that paralyzed the country, the Matignon agreements were signed between Léon Blum’s government and the CGT and CGPF trade unions. Paid vacations were introduced in France in June 1936.

In 1937, the World’s Fair took place in the Trocadero gardens and on the Champ-de-Mars in Paris.

On September 3, 1939, France declared war on Germany. An armed conflict called the “phony war” ensued. In May 1940, Germany launched a major offensive against France, which caused the population to flee in fear of the German advance. The French army found itself on the verge of defeat in a matter of days.

Then came Pétain’s request for an armistice on June 17, 1940. It was signed on June 22, 1940 in the forest of Compiègne. The French territory was now divided into two areas: the “free zone”, governed by Pétain, and the “occupied zone”, ruled by the Germans.

The German anti-Semitic Propaganda Institute was inaugurated on May 11, 1941, three days before the so-called Green ticket round-up, which took place at the place des Petits-Pères in Paris.

Jews were forced to resign from their jobs, in particular in the civil service. They were also forbidden to enter stores and public places and Jewish-owned assets were confiscated.

R. Bourlet

L. Chatelin

The status of the Jews

On October 3, 1940 and June 2, 1941, the Vichy regime passed two laws on the status of the Jews.

What was the decree of October 1940? It excluded Jews from all positions in the civil service, the professional sector, etc. and introduced the notion of a “Jewish race”. It enabled the implementation of a racist and anti-Semitic policy.

The decree in June 1941 extended this to the whole of France, both the occupied and the free zones.

It was the German order of May 29, 1942 that required Jews in France to wear a yellow star. This was circulated by the police.

Rollin high school, Paris, 1940-1944

This large school complex was created from the merger of two junior high schools, Sainte-Barbe-Nicolle, on rue des Postes, and Sainte-Barbe-Lanneau, on rue Cujas.

It is now located at 12, avenue Trudaine in the 9th district of Paris.

The current building was constructed in 1876. It was first named Collège Sainte-Barbe in 1821, then Collège Rollin in 1830, Lycée Rollin in 1919 and finally Lycée Jacques-Decour in 1944.

It is one of the French high schools to have been renamed after one of its teachers, a Resistance fighter, at the time of the Liberation.

Samuel did not stay there long; he was enrolled in October 1940 and stayed there until April 1941.

The Voltaire high school, in Paris

After he was expelled from the Rollin high school, Samuel went to the Voltaire high school in the 11th district of Paris. There were no high schools in 19th district, where they lived.

When he arrived on April 26, 1941 (Paris archives, ref. 2689W36), he was enrolled in 5th grade in class 8 B. The school must have decided that his results were not good enough to keep him in the 4th grade.

64 avenue Simon Bolivar, in the 19th district, is their last known address.

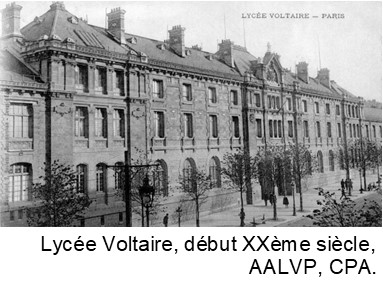

The Voltaire high school

The Voltaire high school at the beginning of the 20th century

Voltaire High School was a public school that offered general and technological courses. It was located in the 11th district of Paris, at 101 avenue de la République.

It was built in 1885, based on a design by the architect Eugène Train. It was inaugurated on July 13, 1891 by the then President of the Republic, Sadi-Carnot.

Eugène Train added some unusual facilities to the school, such as workshops, a library and a projection room that was fitted out by Mr. Gaumont.

The students started school there for the first time on October 7, 1890.

For many years, the Voltaire high school was the only high school in northeastern Paris. In the 1930s and 1940s, school fees had to be paid and only students from fairly well-to-do families could attend. However, a very efficient grant system in a school that was truly republican at the time allowed young people like Samuel to go there.

Until the end of the 1940s, in one part of the school, there were classes from 6th grade to 10th grade. These classes were co-educational.

The high school, however, was for boys only, until it started taking girls in 1973.

However, a high school for girls was founded on the rue Spinoza side, and was open from the beginning of the 20th century until the 1930s.

In 1940, there were no girls in the high school. They were only allowed in the lower grades.

Between 1932 and 1941, the principal was called Roger Rieumajou. He must have known Samuel Aszer, who started at the school in April 1941.

Léon Zampa, a janitor at the high school from 1914 to 1942 says:

“All students followed the same schedule: classes began at 8.30 am and ended at 4.30 pm, with a break for lunch. A supervised study hall was available from 8 a.m. through 6 in the evening. The management provided an after-school snack, tea with bread and butter/jam, for the students who stayed on. Discipline was fairly strict, and students were given a detention on Thursdays for chattering or misbehaving. Each term, the students had to write an essay for each subject. […] Each year, a ceremony took place during which the papers were handed out.”

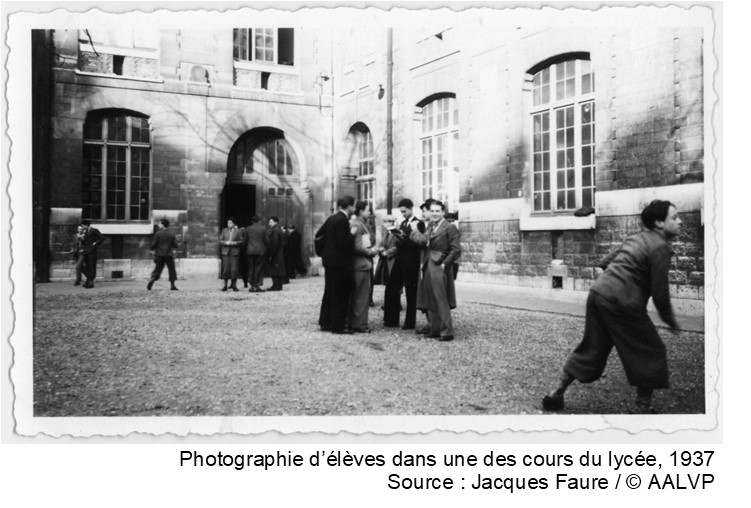

Students in the school yard in 1937

The Voltaire high school today

The school currently caters for around 1000 high school students, 500 in junior high and 75 studying preparatory courses in physics and technology.

The Alumni Association is very active and helped us a great deal in our investigation, as did Marianne Cabaret, a teacher at the school. We would like to thank them for their help.

M. Victoire

L. Phommachanh-Aussiette

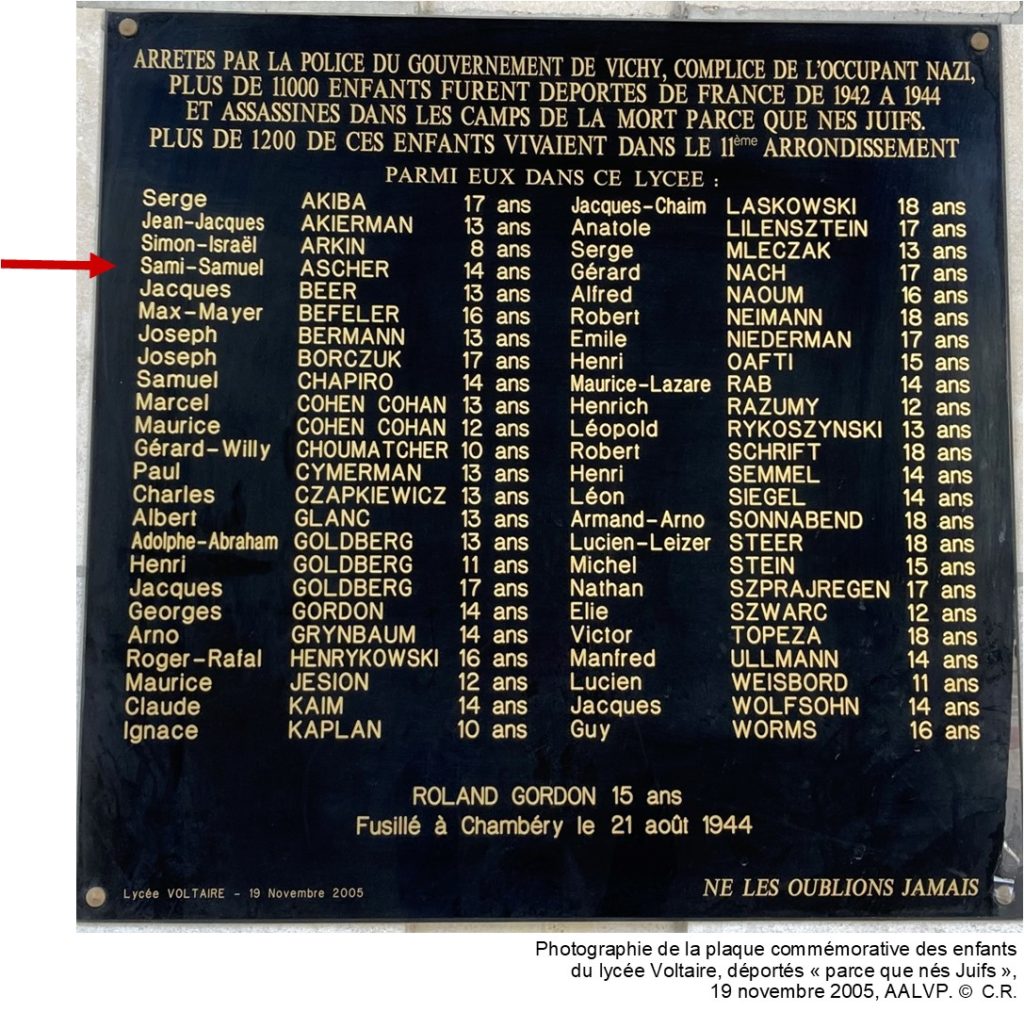

The plaque commemorating children, including those from the Voltaire high school, who were deported and murdered in the death camps “because they were born Jewish”

July 16, 1942, the day that changed everything

On July 16, 1942, the Aszer family was arrested at their home during the Vel d’Hiv round-up.

The record sheets for Herszon and Chawa, taken from the Jewish Register, include the note: “arrested on 16.7.42” (French national archives, ref. F9-5605)

Berthe was arrested together with her parents. She was just 4 years old.

The “Vel d’Hiv”

The Vélodrome d’Hiver (Winter cycling track) was built in 1909 by Gaston Lambert and inaugurated in 1910. It is known as the Vel’ d’Hiv.

It is on rue Nélaton in the 15th district of Paris.

It has a capacity of 17,000 people. Cycling races were held there, as well as circuses, boxing matches, equestrian competitions, political meetings, and even fashion shows.

In July 1942, more than 8,000 Jews were held there during the Vel d’Hiv round-up.

The organization of the Vel d’Hiv round-up

Following the Wannsee Conference of January 20, 1942, during which the “Final Solution” was agreed upon, the most senior Nazi officials planned the extermination of all the Jews in Europe.

In France, the Laval government collaborated with the Nazis in arresting, rounding up and deporting 100,000 Jews.

Some Jews had already been arrested in Paris in 1941 but this operation was on a totally different scale and involved meticulous planning.

The Franco-German alliance agreed to arrest 22,000 Jews between the ages of 16 and 55 in the Paris area and another 10,000 in the Free Zone.

The operation was originally supposed to take place on July 13, 1942, but it was postponed to July 16, 1942.

6000 French police officers took part in the round-ups.

The sequence of events surrounding the round-up

During the night of July 16 to 17, 1942, the French gendarmerie (military police) and militia went to look for the Jews in their homes and forced them to leave.

An excerpt from La Petite fille du Vel d’Hiv (The little girl of the Vel d’Hiv), by Annette Muller, 2012: “Two men entered the room, they were tall, with beige raincoats. “Hurry up, get dressed. We’re taking you away.” they ordered.”

A total of 13,152 people were arrested, including 4,000 children under the age of 16. This is a huge number, but it was only half the number anticipated.

Single people or couples without children were taken to Drancy camp, while families were taken to the Vélodrome d’Hiver.

They stayed about four days in the Vel d’Hiv stadium and were then transferred to the internment camps at Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande.

V. Féréol

S. Kolisso

Y. Joindot

S. Chatelier

The French National archives service sent us two records from the Jewish register (ref. F9-5605); one for Herszon and one for Chana.

We discovered that at the time of the census, the authorities spelled their surname “Ascher” whereas in Metz, it was spelled “Aszer”.

We also see that Berthe’s father’s nationality is listed as “Russian”, which is incorrect since we know that he was born in Poland.

4 days at the Vélodrome d’Hiver

The Aszer family found themselves locked up in the Vélodrome d’Hiver, along with all the other families that had been rounded up.

Berthe was with her parents.

But what about Samuel, Berthe’s brother?

Did he manage to escape the round-up at their home or did he escape from the Vel d’Hiv?

Internment at the Vel d’Hiv

Abram Sztulzaft, known as Maurice, wrote the following letter to his wife Fajga, known as Flora, after the first night he spent at the Vel d’Hiv:

“Vél d’Hiv

My dear little Flora,

[ ]All night long, I didn’t close my eyes. There was no place to lie down, and there were noises and children screaming and crying. Every woman with children is already in a miserable state. Never could we have imagined such a thing. We are just parked here, worse than animals, with no sanitary facilities; two cubicles, always occupied, for thousands of people. You have to wait hours for your turn. For water, it’s the same.”

Excerpt from Je vous écris du Vel d’Hiv, les lettres retrouvées (I’m writing to you from the Vel d’Hiv, the rediscovered letters), Karen Taieb, 2011.

“Lying on the bleachers, I could see the big lights hanging overhead, necks stretched out to the speakers, and strangely enough, I was waiting for the show to start, like at the circus last year. The noise would stop, the lights would go out and maybe Snow White would appear again.

However, Michel and I were thirsty. We wanted to go to the bathroom. But it was impossible to get through the exit lines and, like everyone else, we had to relieve ourselves on the spot. There was piss and shit everywhere. My head hurt, everything was spinning, the screaming, the big hanging lights, the speakers, the stench, the overwhelming heat.”

An excerpt from La Petite fille du Vel d’Hiv (The little girl of the Vel d’Hiv), by Annette Muller, 2012.

Paulette (Pesa) Sztokfisz (1906), had two children, Jacques and Raymonde-Rachel, and lived at 1, passage du Jeu-de-Boules, in the 10th district. Here is what she wrote in a rediscovered letter:

“Vel d’Hiv, the (no date)

Dear brother-in-law and sister,

I am writing these few words to tell you our news, which is very sad. Our health is good but our morale is low.

[..] Do this as soon as possible because we have to leave here for some unknown destination. Hurry up. Bring me a big pillow. Some fruit for Raymonde.

Your sister Paulette.

Bring me the sugar and the preserves because we are not given anything to eat. [..]”

Excerpt from Je vous écris du Vel d’Hiv, les lettres retrouvées (I’m writing to you from the Vel d’Hiv, the rediscovered letters), Karen Taieb, 2011

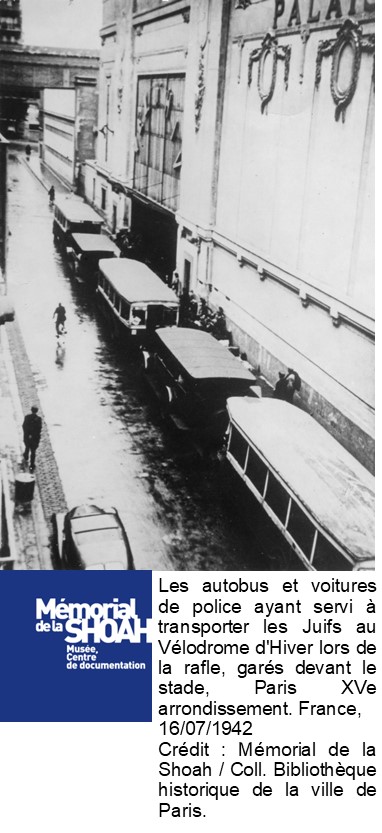

Buses and police cars that were used during the Vel d’Hiv roundup, parked outside the stadium in the 15th district of Paris on July 16, 1942

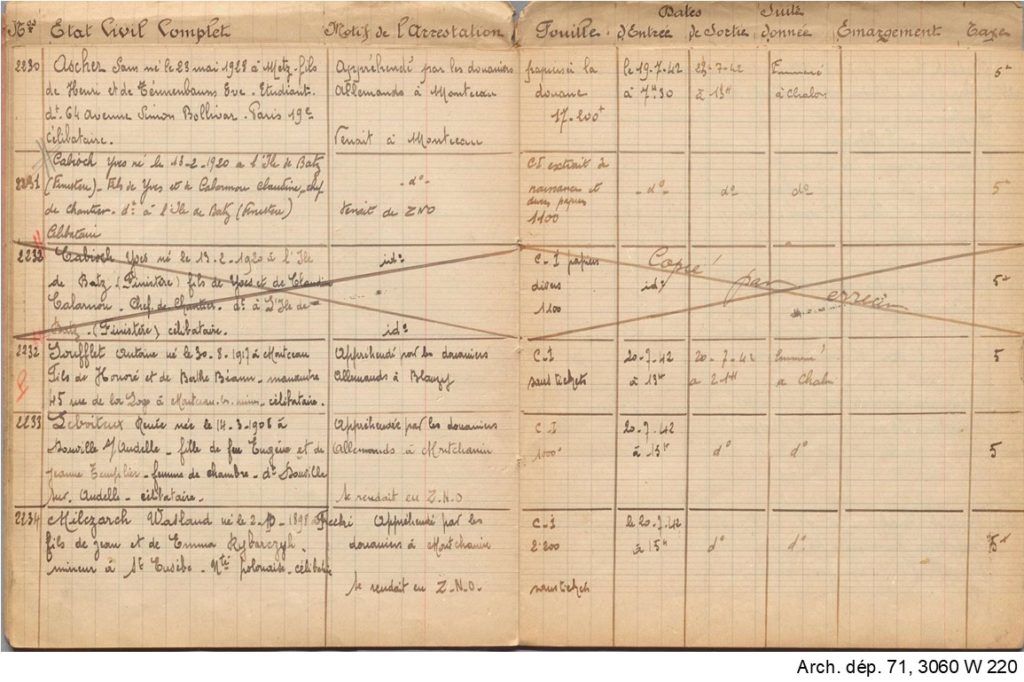

Samuel recaptured in the Saône-et-Loire department

We followed the trail of Samuel, known as Samy, and managed to track him down.

Samuel was 14 years old when he was arrested by German customs officers on July 19, 1942, in Montceau-les-Mines (Saône-et-Loire), probably on the demarcation line.

We imagine that he was trying to cross the demarcation line, as mentioned by one of his cousins, Valérie Tennenbaum, in the documents submitted to the Yad Vashem website in 1992.

Did he escape the round-up on July 16, 1942? Did he manage to escape from the Vel d’Hiv?

A close look at the register of persons stopped by the German authorities at the Montceau-les-Mines police department reveals that he was picked up on July 19, 1942, at exactly 7.30 a.m.

He remained there until July 23, 1942, 1 p.m., after which he was transferred to the prison in Châlons-sur-Saône.

We know that he stayed there until the end of July 1942 since his admission form for the Pithiviers camp is dated August 1, 1942.

Did he see his mother Chawa or his sister Berthe when he got Pithiviers? Did they cross paths? Did they all know that they were in the same camp? We have no idea.

Arrival at the Pithiviers camp

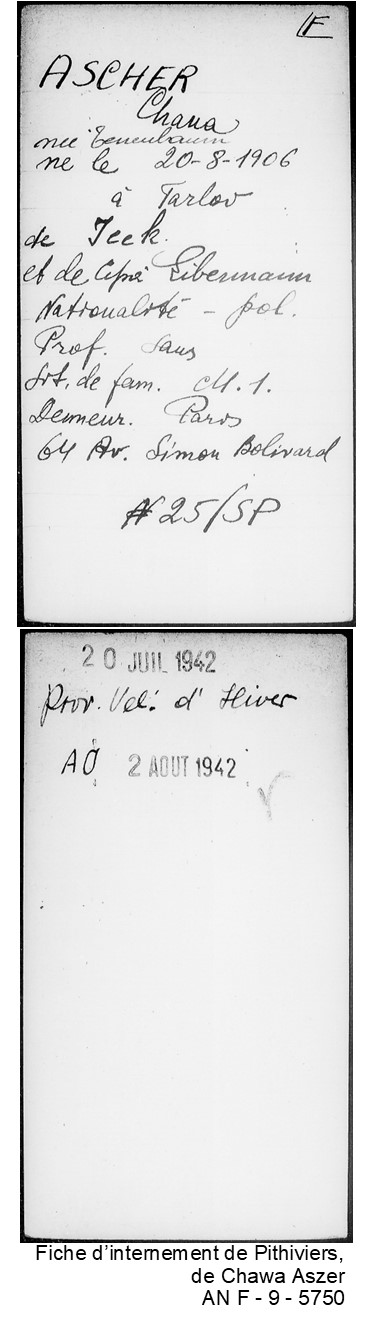

Berthe and her parents, Herzson and Chawa, arrived at the Pithiviers internment camp on July 20, 1942. This is noted on their record card.

Like all families, we imagine that the father would have been separated from his wife and daughter. Did they meet again? Did they ever speak to each other again?

Why Pithiviers?

Before 1941

As early as 1939, the French government set up several camps to assemble refugees and prisoners of war.

The Pithiviers camp became an internment camp after the defeat of 1940. It was in the Loiret department, in the Centre Val-de-Loire region of France.

Pithiviers was chosen because it was quite close to Paris, at about 60 miles away. It was easily accessible by railroad, supplies were available locally, and there were secure facilities, with barbed wire and watchtowers, which had already been used to house prisoners of war.

Internment camps such as Pithiviers were run by the French government. They were also called “transit camps” and were used to hold prisoners before they were deported to Germany.

1941 – 1942

The management of the camp was entrusted to the French authorities under the supervision of the Germans.

On May 14, 1941, during the so-called “Green Ticket” round-up, more than 3,700 foreign Jewish men were arrested and interned, including about 1,700 in Pithiviers, before being sent to Auschwitz.

Many Jews were also arrested during the Vel d’hiv round-up on July 16, 1942. Some 7,600 people were transferred to camps in the Loiret region, where there was not enough room to accommodate them.

The living conditions in the camp were very harsh. Epidemics broke out. The food rations were insufficient. The internees drew pictures or carved sculptures. They were allowed to work, but it was not compulsory.

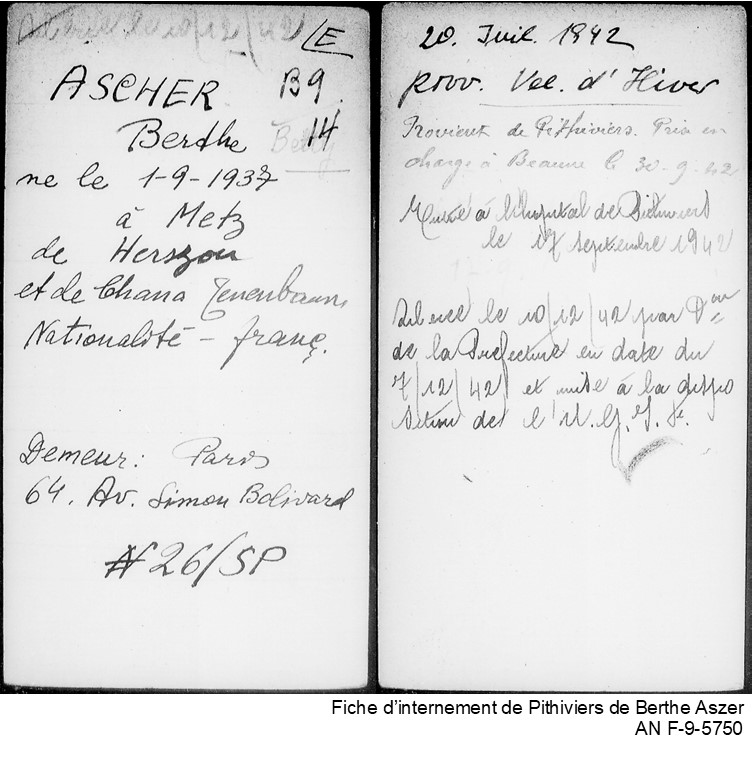

Chawa Aszer’s internment record from Pithiviers camp

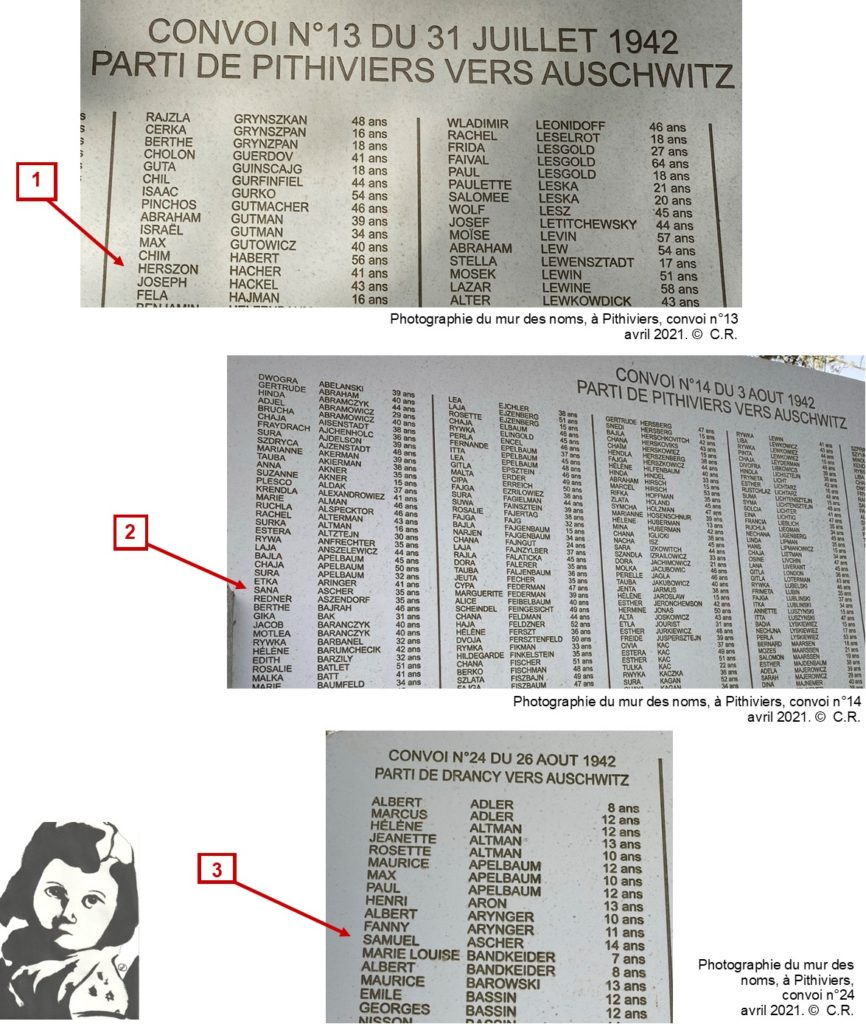

Berthe’s father, Herzson Aszer, was deported on convoy n°13. He left Pithiviers on July 31, 1942, bound for Auschwitz.

Her mother, Chawa Aszer, née Tenenbaum, was deported on convoy n°14. She left Pithiviers on August 3, 1942, also bound for Auschwitz.

Samuel arrived the day after his father left. Did he see his mother again before she was taken away? Did he talk to Berthe?

Six convoys left from Pithiviers:

June 25, 1942, convoy n°4;

July 17, 1942, convoy n°6;

July 31, 1942, n°13 with 690 men, 359 women, 147 children;

August 3, 1942, convoy n°14 with 52 men, 982 women, 108 children;

August 7, 1942, convoy n°16 with 198 men, 871 women, 300 children;

September 21, 1942, convoy n°35 with 168 children.

After September 1942

The Pithiviers camp was evacuated at the end of September 1942 and converted into a concentration camp to house political prisoners until August 1944.

The buildings were destroyed in the 1950s for practical reasons, without the agreement of the memorial associations. Only the infirmary, currently located at 2, rue de Pontournois, was preserved for use as residential accommodation.

The former guardhouse, at the entrance to the camp, is now on Square Max Jacob, at 50, rue de l’ancien camp. It is not even adjacent to the explanatory plaque. There is hardly anything left. Only the accounts of the survivors give an idea of the place. The opposite boundary is near the present-day athletics stadium, behind 14, rue Gabriel Lelong.

In 1957, a monument was erected on the site of the old internment camp, not far from the railroad station. A black urn containing ashes from Auschwitz-Birkenau was laid to rest there. The names of the Jews interned in the camp are engraved on the monument.

In 1992, a memorial plaque commemorating the children who were deported was added to the monument.

The Pithiviers railroad station has been converted into a memorial site. It was to be inaugurated in the summer of 2021, the anniversary of the so-called “Green Ticket” round-up.

R. Bourlet

O. Séjourné

M. Flegny-Mereaux

Photo of the monument in Pithiviers, taken in April 2021

Herzson Aszer, who was deported on July 31, 1942, on convoy n°13, was 41 years old.

He never came back…

Chawa Aszer, who left on August 3, 1942, on convoy #14, was 35 years old.

She never came home…

Samuel Aszer, who was transferred to Drancy on August 22, 1942, and deported on August 26, 1942, on convoy n°24, was 14 years old.

He never returned…

Photos of the Wall of Names at Pithiviers

In memory of Berthe

Berthe, at just 4 years old, found herself alone, with no family.

Berthe Aszer – Let us never forget

Berthe in hospital

We discovered, through the Shoah Memorial records, that at the end of August 1942, Berthe’s maternal grandfather, Icek Tenenbaum, who lived in Nîmes, tried to write several times, on the recommendation of the Chief Rabbi of Colmar, Ernest Weill, to Raoul Lambert, Director General of the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews), because he was worried about his grandchildren. But to no avail…

Berthe spent the entire month of August in the camp and was finally admitted to the hospital in Pithiviers on September 17, 1942. We do not know the reason for this. Either she was sick or someone (perhaps from the Red Cross?) made her appear to be sick…

She stayed there until the end of the month.

Pithiviers Hospital

A little history

Ever since the Middle Ages, there has been a hospital in Pithiviers called the Hôtel-Dieu. It was originally run by monks. In 1902, the hospital was relocated to boulevard Beauvallet, where it still stands today.

Two testimonies give us some information about time spent at the hospital :

1/ Research work on the site https://www.tharva.fr/, where we find excerpts from the letters of Bernard Jankelovitch, who was hospitalized from September 24, 1942 to March 25, 1943, at the age of 18.

2/ Madeleine Fauconneau du Fresne, in her account De l’enfer des hommes à la cité de Dieu (From the hell of men to the city of God), published in 1947, then republished under the title L’Etoile blanche, Mémoire d’une Juste 1940-1945 (The White Star, Memory of a Righteous Woman 1940-1945) edited by E. Rougier, in 2020. Madeleine Fauconneau du Fresne was granted the title of Righteous Among the Nations on August 15, 2018 (case n° 17046).

1941-1945

The hospital was run by a Dr. Gautier, who was also the camp’s chief physician. The nursing staff was often made up of civilians and “the city hospital was run by the nuns of Saint Vincent de Paul,” wrote Madeleine Fauconneau du Fresne.

This is how she described it when she visited her friend Yvonne Netter, a Jewish activist lawyer who was interned in the Pithiviers camp and then admitted to the hospital: “vast gardens, sandy paths, then a large overgrown area over which an old man and an enormous plow horse were toiling away.”

Relatives were not allowed to visit the camp internees in hospital. Two gendarmes kept watch. Madeleine, however, persisted and managed to get in to see her friend: “There she was, in a clean bed, with real sheets. […] In the big, bright, gleaming room, the beds were all white and all the same.”

Bernard, from his hospital bed, wrote to his parents, courtesy of Yvonne: “Don’t you believe Mom that in the hospital we are free, we are locked up, we are still Jews. There are gendarmes at the door.” (L. 30.9.1942).

The Jews were grouped together in a dormitory called the Hervé Room. The women and men were all in the same ward. They were separated by a screen.

Jews were not allowed to go into the gardens:

“We are guarded by police. We’re not allowed to go out into the garden, we’re separated from everyone else, the Jews are separated from everything.” Bernard wrote to his mother (L. 7.10.1942).

There was not much food. Breakfast at 7.30 a.m. « a little burnt coffee », a midday meal at 11 a.m. and one in the evening at 5 p.m.

Bernard continues:

“The food is like everywhere else, potatoes, carrots and turnips… on Sundays we are given the usual little bit of meat and they don’t give us much of anything… Tonight we had soup and three boiled potatoes with a little salad.” (L. 30.9.1942).

In the room, adults and children were all mixed together:

“Opposite Yvonne, I saw a little girl of five years old. She was sitting quietly on a small chamber pot and, having finished with it, carefully put it away beside her. “We don’t know what language she speaks,” said the blessed Mother with a sigh. “She doesn’t answer any questions.” […] Then one day, the five-year-old girl opened her mouth. She said, “My name is Betty” and she began to sing. Her father had been deported one way, her mother another way and her brothers too. She was left all alone in this world, this vast world… She didn’t stay there very long. At the age of six, she was recaptured, deported, and sent to the crematorium. No one knows anything more about little Betty, except God. […] They also brought to the hospital “the politicians” as the blessed Mother discreetly called them: they were “tough guys” […] But sometimes she found the time went slowly and life seemed long. “You are lucky”, she said to me, seeing me leaving the evening, ”you are “goin’ to jail.””

J.Moll

M. Delbeke

Madeleine’s testimony is all the more precious because in it, we find a trace of Berthe.

Our research made us wonder about organizations such as the Red Cross during the time of the Vichy regime.

What role might the Red Cross have played during the Vel d’Hiv round-up or in the internment camps in France?

Might a Red Cross social worker have helped Berthe?

It would seem so…

The Red Cross in France

The French Red Cross is a French humanitarian aid charity founded in 1864. Its international headquarters are in Geneva, Switzerland. Its purpose is to help French civilians as well as foreigners arrested for political, administrative or religious reasons.

For two years, from 1940 to 1942, the French Red Cross distributed food aid and toiletries in German-run camps and prisons with political sections, as well as in camps in the Free Zone (Rivesaltes, Noé, Vernet-d ‘Ariège, etc.).

In March 1941, permanent Red Cross centers were set up in the camps at Compiègne, Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande, and then another in Drancy in September 1941. They distributed bed linen, blankets for the infirmary, extra food, flour, peas, pasta, etc., although only limited quantities were allowed.

In September 1942, the German authorities decided to discontinue the Red Cross social service at Drancy camp. From then on, the UGIF (General Union of Israelites in France) assisted the Jews. In May 1943, the French Red Cross was also stopped from helping internees’ families. It was replaced by the Secours National, a charitable organization dependent on the Vichy government that was responsible for monitoring the activities of organizations that helped civilians during wartime.

Lastly, in 1945, the Red Cross was involved in the repatriation of prisoners of war and deportees.

It should be noted, however, that the Red Cross received some criticism for not alerting international bodies to the treatment of prisoners in the camps.

E. Guillemot

K. Bregnard

“The Gringoire cookie factory in Pithiviers brought us a lot of cookies and gingerbread for the children. Mrs. Rolland (who lived on rue de Beauce) was there at the camp and was able to save one child: Betty Ashar. Like me, she was a member of the Red Cross and, like me, deplored the “cautiousness” of the Red Cross: the fate of the Jews was not its primary concern.” Taken from Annette’s letter to the newspaper l’Express, 1990, cited in Annette Monod, l’Ange du Vel d’Hiv de Drancy et des camps du Loiret (Annette Monod, the Angel of the Vel d’Hiv, of Drancy and of the Loiret camps), F. Anquetil, 2018

It would seem that “Betty Ashar”, mentioned by Annette Monod, was indeed Berthe Aszer.

Testimony of Annette Monod, then a social worker with the French Red Cross, who was initially sent to the Vélodrome d’Hiver and then to the Beaune-la-Rolande camp:

“They are arresting the women and children. They are at the Vel d’Hiv. Since you are familiar the issue, go there (…) Alerted by telephone by the French Red Cross, off I went. It was a jumble of women and children, 12,800 people of all ages were crammed in. It was impossible to organize anything. The physical conditions were terrible: no toilets, no quiet corners for the sick. I heard that a transfer to Beaune-la-Rolande was going to take place: the foreign Jews from the Loiret camps had been deported and the camp could take in a new contingent.” cited in Annette Monod, l’Ange du Vel d’Hiv de Drancy et des camps du Loiret (Annette Monod, the Angel of the Vel d’Hiv, of Drancy and of the Loiret camps), F. Anquetil, 2018.

Berthe at Beaune-la-Rolande

In September 1942, the Pithiviers internment camp was evacuated since it was to be used for political prisoners.

Berthe, who was still in Pithiviers at the time, was transferred to the Beaune la Rolande camp, as were many other children.

She arrived in Beaune on September 30, 1942.

All alone, she had “celebrated” her 5th birthday on September 1.

The Beaune-la-Rolande camp

Where was the camp?

Beaune-la-Rolande is approximately 60 miles south of Paris, 30 miles northeast of Orléans, 16 miles northwest of Montargis and 12 miles southeast of Pithiviers.

What was the site used for before 1941?

In 1937, the municipality of Beaune-la-Rolande created a sports field and built a gymnasium with showers open to the public.

In 1938, although the local population did not really know why, the seven-acre site was taken over and a number of barracks (modular, portable “Adrian barracks”) were built, which later became the “camp”.

Everyone thought that this camp was intended to accommodate the German prisoners taken at the beginning of the war.

What happened when the camp opened?

At first, the camp was used to house 22,000 French prisoners of war following the defeat of France on Tuesday, June 18, 1940. They were held in appalling conditions.

The German authorities soon extended the camp. Houses and a farm were taken over and the road to Auxy was cut off. The commander was an Austrian officer.

The Germans ran the camp, but there were too many prisoners. They were therefore sent to civilians’ homes, primarily to be fed, but also to serve and help with work..

In May 1941, after the so-called “green ticket” round-up, more than 3,000 Jews were arrested, of which 2,000 were interned in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp under the orders of the German authorities.

At the beginning, visits and outings were allowed on the condition that the internees were present at the check-in every day.

The internees were housed in barracks, all piled in on top of each other, on dirty straw, which was never changed, and with no sanitary facilities.

In the summer of 1942, more than 3,000 people were interned in Beaune, following the roundup at the Vélodrome d’Hiver, in dreadful conditions.

Two convoys left Beaune-la-Rolande for Auschwitz:

June 28, 1942, convoy n°5,

August 5, 1942, convoy n°15.

When Berthe arrived in Beaune-la-Rolande, she had lost her father, her brother, who she probably never saw again, and worst of all, she had been violently separated from her mother.

After July 1943

Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of the Drancy camp, ordered the closure of the Beaune-la-Rolande camp on July 12, 1943.

In 1947, the camp was destroyed. An agricultural school was built on the site.

In October 1964, it was converted into a women’s agricultural college, when the construction work, supervised by the architects Blareau and Guillaume, was completed in 1963-4.

In 1967, the site became a professional agricultural high school.

In 1965, a memorial was erected. The present school is on the “rue des Déportés” (Deportees’ Road).

L. Cailler

G. Lucas

These are the words of Annette Muller, in La Petite fille du Vel d’Hiv (The little girl of Vel d’Hiv), 2012. At the time, the children had just been separated from their mothers, who were deported on convoy n°15.

“At night, lying on the filthy straw, I cried, biting my fists to muffle my cries. I could not bear to be without my mother. […] For days and days I could not stop crying, stretched out on the straw that was teeming with vermin. I did not want to leave the hut. Michel dragged me outside to get some fresh air. He cleaned the excrement off me. […] We wandered, sleeping in one barrack or another, disheveled, skinny, devoured by lice, looking for a little food. We wandered along the ground littered with filth with rats running everywhere. We ate grass if we could find any.”

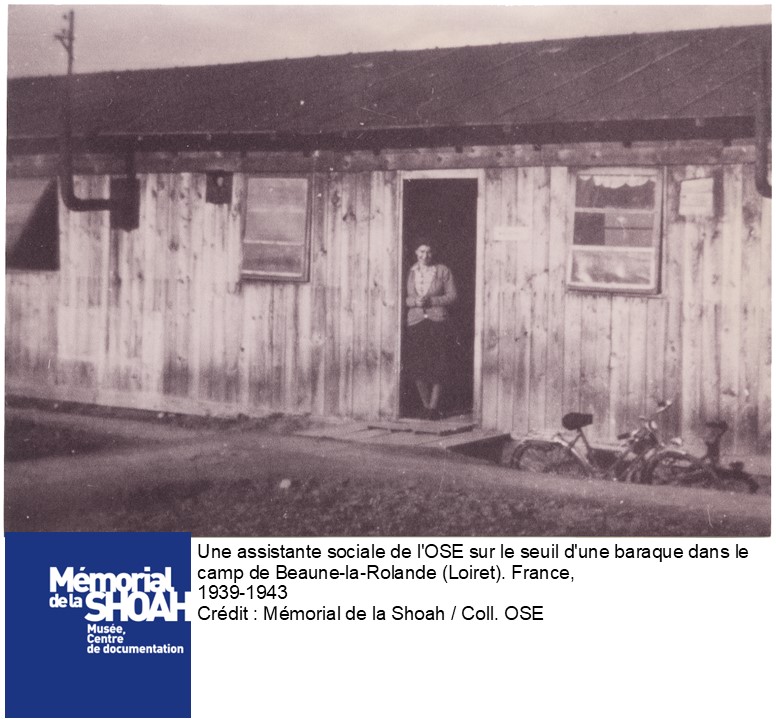

A social worker at the door of a barrack hut in the Beaune-la-Roland camp, 1939-43

Berthe in the Montreuil children’s home

According to a decision of the Prefecture of Loiret, on December 7, 1942, Berthe was liberated on December 10, 1942. She left the Beaune-la-Rolande camp and was handed over to the UGIF, the General Union of French Jews.

She was then sent to live at the Montreuil-sous-Bois Center, a UGIF children’s home.

From then on, she became a “blocked child”: such children were taken out of the camps but were still classified as prisoners.

The UGIF homes

The UGIF’s role was to represent the Jews in dealings with the public authorities, particularly in matters of assistance, welfare and social reclassification.

Some centers were used to house Jews, in particular Jewish children.

In August 1942, there were four UGIF homes for children whose parents had been arrested. They were center 40, in Neuilly; center 30 at 9, rue Guy-Patin in Paris; center 41 at La Varenne and center 28 on rue Lamarck in Paris.

Center 52, in Montreuil was opened at the end of October, 1942.

In June 1943, two more children’s homes were opened; center 56 in Louveciennes and center 64 in Saint-Mandé.

These homes grouped together:

1 So-called “free” children, placed there by their parents or “abandoned” for various reasons.

2 “Blocked” or isolated children, who were interned and then released from the camps and were then assigned to the UGIF. Foreign children or those born of foreign parents were registered and were said to be “deportable, i.e. liable to be deported at any time.

The home at Montreuil-sous-Bois

The UGIF home in Montreuil, where Berthe was staying, was at 21, rue François Deberque.

The building is now the annex of a nursery school.

Most of the supervisors were Hungarian Jews. There were 9 supervisors and the center had 768 employees in May 1943.

The managers of this center were Mrs. and Mr. Fruchter. She was a French citizen and husband was Hungarian.

The number of children in the home did not vary much: There were 15 in April 1943, 19 in December 194, 21 in May 1944 and 15 in July 1944.

During the school year, the children staying in the center went to school. Children who were “blocked”, were subject to strict rules: if any of them were allowed out, the Police Department required a list of their names and of the visitors who took them.

During the last few months of the occupation, the fate of the centers and the children staying in them was becoming increasingly precarious. They were afraid that there would be a roundup. When Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of the Drancy camp, asked for a list of the residents’ names, this worried them further.

Only one convoy left Le Bourget railroad station in June 1944, but towards the end of July, Alois Brunner wanted to make sure that the next convoy would be full and ready to leave, and therefore decided to round up the children in the UGIF homes.

Between July 20 and 24, 1944, in the middle of the night, the homes were raided, including the one in Montreuil, where Berthe was staying. Eighteen children and four social workers were rounded up from center 52. We found this information in a report written by J. Laloum, “L’UGIF et ses maisons d’enfants : le center de Montreuil-sous-Bois”, (The UGIF and its children’s homes: the Montreuil-sous-Bois center) in the newspaper Le Monde juif (Jewish world), Oct-Dec. 1984.

A. Duthuillé

T. Catherine dit Cariot

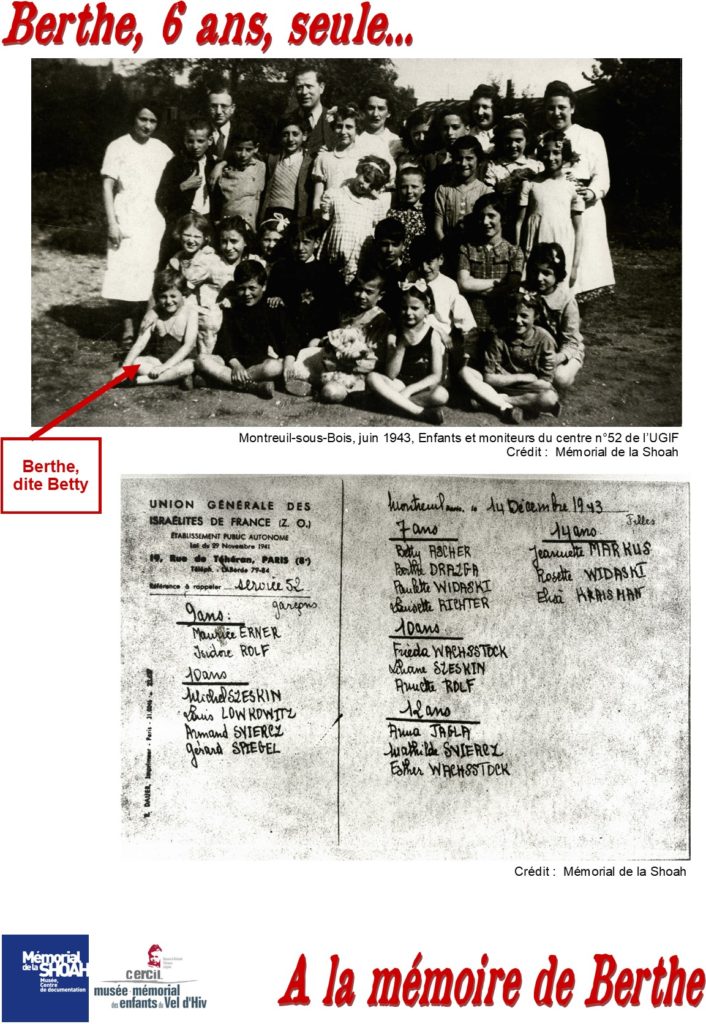

A photo of the supervisors and children in, the UGIF home at Montreuil-sur-Bois, in June 1943. Berthe, known as Betty, is on the bottom left.

Berthe in Drancy

Eighteen children from UGIF center 52, in Montreuil-sous-Bois, were rounded up in July 1944.

Berthe was one of these eighteen children. She was taken to Drancy on July 22, 1944.

At only 6 years old, she had already experienced three internment camps: Pithiviers (63 days), Beaune-la-Rolande (70 days) and Drancy (9 days), one stay in a hospital (14 days), a children’s home (590 days) and two arrests, two years apart.

Drancy, or la cité de la Muette

Drancy camp was in Seine-Saint-Denis, a suburb of Paris in the Île-de-France region of France.

In the 1930s, some low budget apartments were built for families from Drancy. It was very modern and bold project at the time! The housing complex was built between 1931 and 1937.

The architecture of these buildings was very distinctive, since standard, prefabricated materials were used throughout. The site was intended to provide 1,250 housing units. There were a series of 14-storey towers, each with two long 2-3 story buildings adjoining it. The buildings were nicknamed “the comb”, and were built in the shape of a horseshoe around a space called the “entrance courtyard”.

Then, in the 1940s, the unfinished building complex was used as an internment camp.

The French internment camps were official detention centers or refugee or prisoner of war camps, and then assembly camps for Jews.

In August 1941, Drancy became an assembly and transit camp.

From August 20, 1941 to August 17, 1944, nearly 80,000 people (men, women, children) were interned in the Paris suburb, simply because they were Jews.

On September 20, 1941, the Red Cross was given permission to set up an office in the camp. They provided meals to the camp, which were delivered by a Jewish Solidarity Committee “de la rue Amelot“.

After that, new furniture for the dormitories was delivered: bunk beds, straw mattresses and, blankets. The internees were allowed to receive letters every two weeks.

About 30 people died in the camp between October and November 1941. During this time, 750 interned patients were released under the supervision of a commission including a doctor from the prefecture and some German servicemen. In December 1941, some very sick people were transferred to various hospitals.

On July 3, 1942, at around 6 a.m., the French police picked up all the patients and took them back to Drancy. The gendarmes who were in charge of searching the patients often took advantage of the opportunity to confiscate a little of what they wanted for their own use or to sell on the black market. Visitors were not allowed.

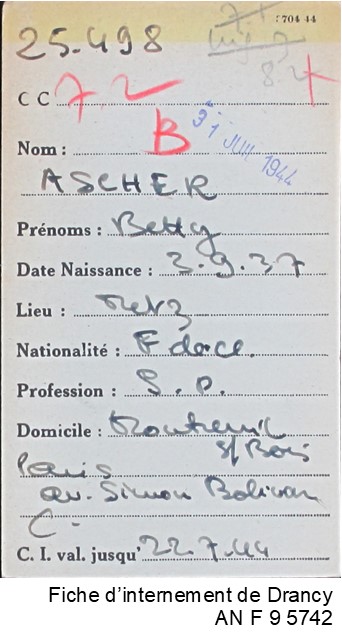

Berthe’s internment record from Drancy camp. Her name is given as Betty, and her surname spelled Ascher rather than Aszer.

Up until July 1943, 63 convoys departed from Bourget-Drancy railroad station. After that, they left from Bobigny. In total, more than 65,000 people were sent to the killing centers, mainly to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

In the second half of 1942, there were large numbers of new arrivals and not enough of anything to go around. During the worst raids in 1942, there were 7,000 people in the camp, even though its maximum capacity was only 5,000. Nine out of ten Jews passed through Drancy camp during the Holocaust.

In early summer 1944, as the Allied troops were advancing, thousands of Jews being held in southern cities were transferred to Drancy to be deported.

The final convoy left Drancy on August 17, 1944. The deportees were marched to the Bobigny train station. The march was led by the Nazi officer Aloïs Brunner, who had taken charge of the camp a year earlier, on June 18, 1943.

The camp was closed in August 1944.

Before they left, the Nazis burned all the camp records so that there would be no evidence of the torture they had inflicted, but two internees from the camp managed to salvage a file containing the names of all the deportees who had passed through the camp.

The camp was then entrusted to the Resistance. On August 20, the remaining internees were liberated.

After the liberation of Paris, from August 19 through 24, 1944, Drancy camp was used as a detention center for people suspected of collaboration, such as the writer and director Sacha Guitry and the singer Germaine Lubin, among others.

M. Léglise

M. Gaudin

The three forced labor camps in Paris

There were three satellite camps attached to Drancy. They were in Paris itself, and were used for forced labor (Dienststelle Westen): Lévitan, at 85-87 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin, in the 8th district; Austerlitz, at 43 quai de la Gare, also in the 8th district; and one at 2, rue de Bassano, the former mansion of the Jewish family Cahen d’Anvers, where they made haute couture fashion garments and luxury furs. L. Klejman’s grandmother spent the last few months of her life there before she was deported.

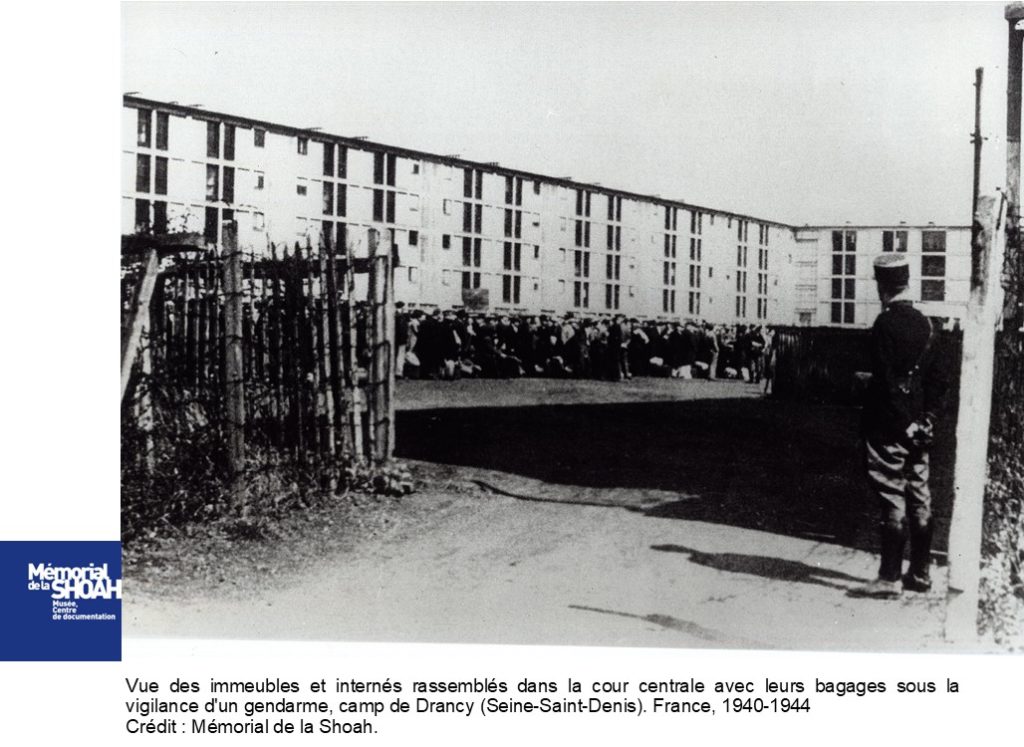

View of the buildings and internees gathered in the central courtyard with their luggage, watched by a police officer, Drancy camp, Seine-Saint-Denis, France, 1940-1944.

Photo credit: Shoah Memorial in Paris

Drancy today

At present, between 600 and 700 people rent the apartments in the U-shaped building. These were restored for their original purpose at the end of the war.

The Drancy camp has been on the list of protected monuments and sites since May 25, 2001. It was on this day that Catherine Tasca, the French Minister of Culture, signed a decree designating la Cité de la Muette an architectural monument.

In 2009, during renovation work, graffiti was found on some slabs of plaster. It had been engraved or written in pencil, mostly by Jewish internees. The oldest graffiti found dates from August 1941. The writers inscribed their name and the date of their arrival at the camp, and in some cases, later on, they added the date on which they left. The names of some people deported on Convoy 77 were among them.

On September 21, 2012, at the request of the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah, the then President of the Republic, François Hollande, inaugurated the Shoah Memorial in Drancy. Now a permanent, well-documented exhibition, it gives visitors the opportunity to learn about the history of the Cité de la Muette and the central role that Drancy camp played in the deportation of French Jews during the Second World War.

M. Rigaud-Léonce

Photo taken inside the camp at Birkenau

Berthe aboard Convoy 77

The date of the departure of the next convoy was set for July 31, 1944.

The convoy on which Berthe was deported included more than 300 children.

There were 60 children in each cattle car, with only two or three adults and just one container of drinking water between them.

Convoy 77

The Convoy 77 non-profit organization has compiled a list of 1306 men, women and children who were deported on convoy n° 77.

On July 31, 1944, Convoy 77, the last large convoy to deport Jews from Drancy, left Bobigny station bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center.

982 men and women.

324 children.

The convoy left Drancy by bus. There were 1306 deportees, including more than 300 children. They were taken to the Bobigny railroad station. There, the Jews were loaded into cattle cars.

First of all, there were five stops at towns in France, at Épernay, Châlons-sur-Marne, Bar-Le-Duc, Novéant and Metz.

The convoy continued its journey into Germany, passing through Saarbrucken, Frankfurt am Main, Fulda, Erfurt, Leipzig and finally Dresden.

From there, it crossed the border into Poland and arrived in the town of Gortliz. It then passed through Cosel and Katowice before arriving at the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center.

The convoy left Drancy, France, on July 31, 1944 and arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland, on August 3, 1944.

M. Ndala-Bituala

M. Allimonnier

S. El Hakkouni

B. Lesage

Berthe at Auschwitz-Birkenau

Photo taken inside the camp at Birkenau

Berthe was murdered on her arrival at the Birkenau camp on August 5, 1944. She was just 6 years old.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center

Built in 1941, two miles from the Auschwitz camp on the Brzezinka site in Poland, the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp was a killing center. It was the largest camp ever built. It covered an area of over 430 acres (175 hectares) and was divided into several sections.

Founded by Heinrich Himmler to implement the “Final Solution”, this place witnessed the deaths of more than 1.1 million men, women and children. Most of them were Jews, since the Nazi policy was based on a racist and anti-Semitic ideology.

Auschwitz-Birkenau included five gas chambers with crematoria, each with a capacity of 2,500 prisoners.

Between 1942 and 1944, it became the main mass killing facility, where Jews were tortured and murdered. In addition to the mass murder of more than a million Jewish men, women and children, and tens of thousands of Polish victims, Auschwitz-Birkenau also served as a killing facility for thousands of Gypsies and other prisoners of various, mainly European, nationalities.

The elderly, the sick, the infirm, mothers with children, pregnant women, infants and people deemed unnecessary to the German war economy were all sent to the gas chambers as soon as they arrived.

And that is what happened to Berthe

At the end of November 1944, Heinrich Himmler gave the order to halt the operation of the gas chambers and to dismantle the equipment. Faced with the rapid advance of the Red Army, the camp was evacuated as a matter of urgency on January 17, 1945. “58,000 prisoners were forced onto the roads on the “death marches”.

At least 1.3 million people were deported to Auschwitz, including 1.1 million Jews. Of these, nearly a million were murdered, including 69,000 Jews from France.

What remains of Auschwitz now?

The enclosures, barbed wire, sidings, docks, barracks, gallows, gas chambers and crematoria at Auschwitz-Birkenau reveal what happened there during the Holocaust.

The camp has been preserved in its original state, untouched by restoration or building work.

The Auschwitz-Birkenau camp complex comprises 98 brick and wooden structures and approximately 300 ruins, including those of the gas chambers and crematoria.

The Germans blew up the gas chambers and crematoria with dynamite, in an effort to destroy the evidence.

L. Ferbus

K. Ventolini

Photo of the memorial stone at Auschwitz-Birkenau

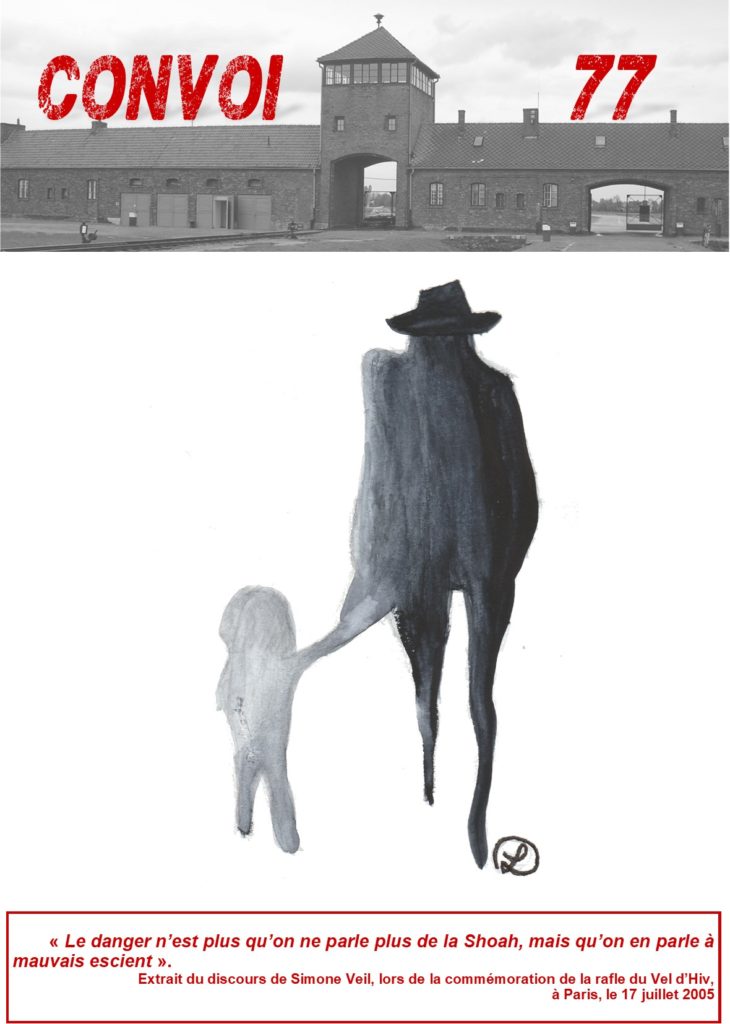

“The danger is no longer that the Shoah will not be talked about, but that it will be talked about in the wrong way”. From Simone Weil’s speech at the commemoration of the Vel d’Hiv round-up, held in Paris, July 17, 2005

Link to our journal (in French) about Berthe’s life

https://fr.calameo.com/read/006788130ef57446315c7

Français

Français Polski

Polski