Bernard BERKOWICZ, 1932 – 1944

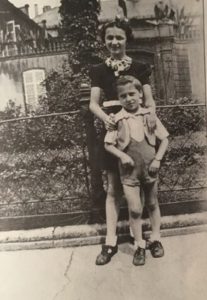

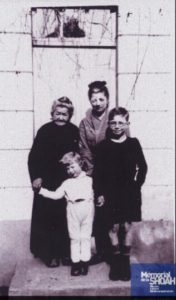

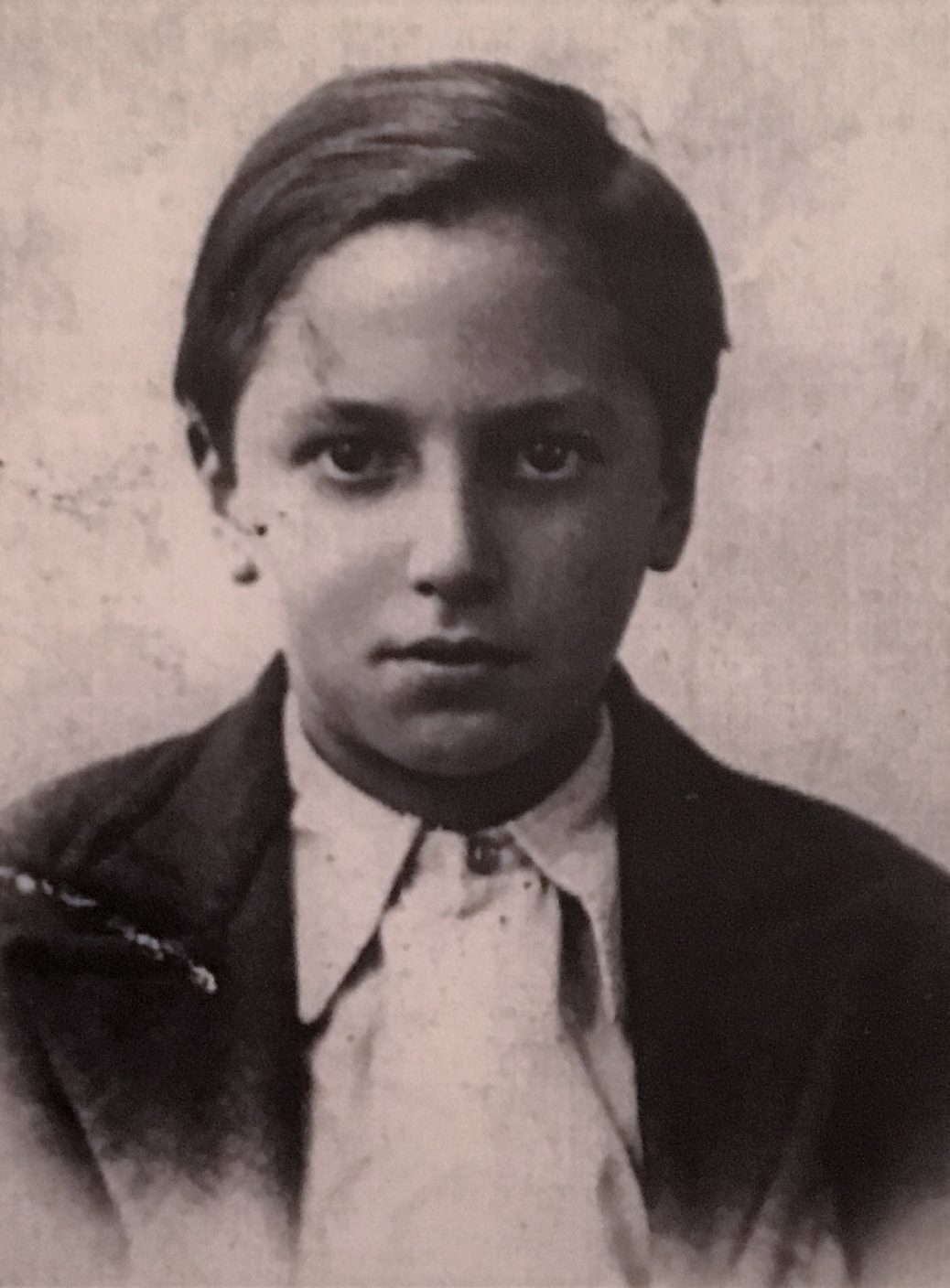

Photograph of Bernard Berkowicz, found by Richard Niderman among the belongings of his brother, Joseph.

This biography was produced by the 12th grade class of the Louis Vincent high school in Bernard Berkowicz’s home town of Metz, where he was born in the in the Belle-Isle Hospital on November 26, 1932 He was the third child of Moszek and Mariéna Berkowicz.

1. OUR WITNESSES

In the course of our research, we had the opportunity to meet with several witnesses :

Evelyn Askolovitch

Ms. Askolovitch was born on July 15, 1938 in Amsterdam to German Jewish parents. On March 12, 1943, Evelyn Askolovitch, then aged 4 ½, and her parents were denounced to the German authorities and arrested. Interned in two camps, Vught, a concentration camp, and then Westerbork, a deportation camp, both in the Netherlands, they were deported in February 1944 to the Bergen-Belsen camp until January 21, 1945. By using a forged certificate of Honduran nationality obtained through a Swiss friend, the family was able to escape deportation to Auschwitz.

During a video conference on January 4, 2021, Ms. Askolovitch told us about her few remaining memories of being deported. This gave us a better understanding of Bernard’s family’s story, even though there are many differences between the two. Ms. Askolovitch was interned in concentration camps, whereas the Berkowicz family, including Bernard, were sent to a combined camp and killing center, where they were murdered.

Richard Niderman

Richard Niderman was born after the war in Forbach, in Alsace-Moselle. Ever since his brother Joseph died in 2014 he has been researching his story and that of his sister, Charlotte, who were deported to Bergen-Belsen a few days before Convoy 77 set off. Since their father was a prisoner of war, they were not deported to Auschwitz but to a concentration camp, from which they later returned. Among Joseph’s belongings, Richard found the above photograph of Bernard Berkowicz, which led him to search for more information about him in the Shoah Memorial archives. In so doing, he felt that he was honoring “sixty years of loyalty to a tragic memory”.

We initially contacted Richard Niderman by e-mail, and then organized a videoconference meeting on February 18, 2021. He told us what he knew about his family history. This allowed us to better understand the life of Jewish families and children separated from their parents.

Robert Frank

Robert is a prime witness. Even though the Covid 19 lockdown meant that we could not meet him in person, he was able to provide us with a lot of information about his history. Originally from Metz, where he was born on November 11, 1929, he is the only person to have known Bernard, who’s journey was in part similar to his own. In December 1939, his family left to take refuge in Royan, in the Charente-Maritime department of France. A few months later, at the end of 1940, the Frank family, like the Berkowicz family, left for Festalemps in the Dordogne department. It was only then that the two families really got to know each other. They stayed there for two years until they were arrested during the roundup at the Philharmonic Hall in Angoulême, in October 1942.

Through various email exchanges, Robert Frank shared his memories of Festalemps with us. It was there that he knew Bernard Berkowicz and his family. He was therefore able to tell us about life in the village, and in particular what he remembers about Bernard.

Daniel Urbejtel

Daniel Urbejtel was born on February 19, 1931, in the 12th district of Paris. He and his brother Henri both stayed for a time at the Lamarck Center. Even though they do not have any specific recollection of Bernard, they must have known him since, like him, they were arrested during the night of July 21-22, 1944 and deported on Convoy 77. This has helped us to better understand what Convoy 77 was like. The two brothers, unlike Bernard, came back after having been deported and are among the last survivors of the convoy.

We would like to thank all these witnesses for the information they gave us and for their messages of tolerance and hope.

2. OUR MAIN SOURCES

* Residential records

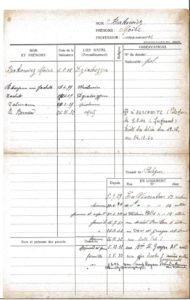

The municipal archives department in Metz kindly provided us with the Berkowicz family’s address card. The residence card system was used in Alsace-Moselle from 1871 until 1940. For each household, they show the composition of the family, their professions and all changes of residence. When so many families left Metz in 1940, they were often discontinued. However, the Berkowicz list was completed one last time in 1960 in order to mention Bernard’s death in Auschwitz.

The residence card of Moszek Izbicki, a brother-in-law of Moszek Berkowicz, was also very helpful.

Moszek Berkowicz’s residence card (Metz Municipal archives)

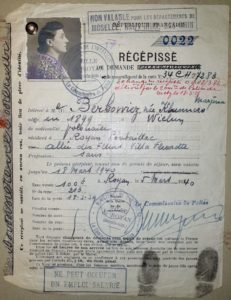

* Refugee records from the Charente-Maritime department

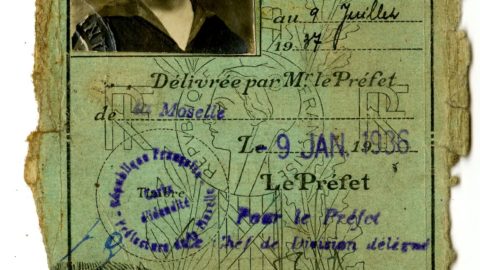

The Charente-Maritime Departmental archives office in La Rochelle kindly sent us a file requesting the renewal of Mariéna Berkowicz’s identity papers. It was put together when the family took refuge in Royan in 1940. A similar file was sent to us for Moszek Izbicki. These files are interesting because they allow us to trace the shared history of the two families in Royan. From this file we also have an identity photograph of Mrs. Berkowicz. We note that she was forbidden to return to the Alsace-Moselle region, which by then had been reintegrated into Germany.

Extract from the file put together for the renewal of Mariéna Berkowicz’s identity card in Royan in March 1940.

(Charente-Maritime Departmental archives)

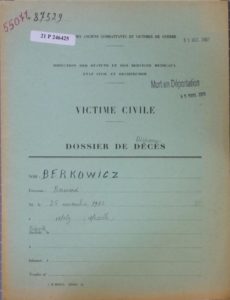

* Bernard’s military record

The Convoy 77 association gave us access to Bernard’s military records. Since he was a French national, Bernard was drafted in 1952. When he did not respond to the call-up, he was considered as a deserter and the army carried out an investigation, which was only completed in 1960, when he was found to have died.

It was then that his death was recorded on the family’s residence card.

Extract from Bernard Berkowicz’s military record (1951-1960) made available by Convoy 77.

* A voice recording of Alice Peyronnet

Mr. Guy Peyronnet kindly sent us a 2008 recording in which his mother talks about the Jewish families who took refuge in the village of Festalemps during the war. She speaks in particular of the Schuhmanns, who syated with her and, although she does not mention them by name, of the Berkowicz family, who lived with her parents-in-law and her young brother-in-law, Fernand.

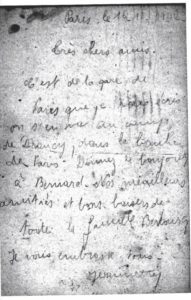

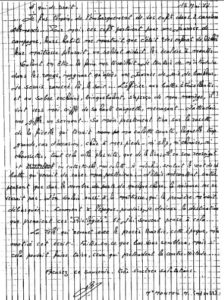

* Letters from the Berkowicz children

Robert Frank kindly entrusted us with a collection of five letters written by the two eldest of the Berkowicz children, Jacheta and Samuel, to the Peyronnet family between October 11, 1942, which was two days after the roundup in Angoulême, and October 31, 1942, four days before their departure for Auschwitz. After the war, Fernand Peyronnet entrusted these letters to Robert Frank, who submitted the originals to the Shoah Memorial in Paris. The fact that they were written by the children could suggest that the parents had a poor command of French. They are of great interest because they allow us to follow the tragic journey of the family between the roundup and their deportation and to learn more about the family members, their links with the Peyronnet family and the residents of Festalemps. In these letters, Bernard is always mentioned.

* Polish records

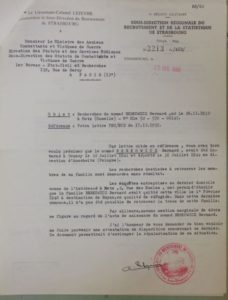

Thanks to Véronique, a French-Polish student at our high school, we contacted the authorities in Poland in the towns where the Berkowicz parents originally came from. The district of Dzialoszyn, where Moszeck and his daughter Jacheta were born, holds no Jewish records. We had better luck, however, with Wielun, where Mrs. Berkowicz was born. The authorities there sent us Bernard’s parents’ marriage certificate.

The Berkowicz parents’ marriage certificate, dated 1926 (Wielun Municipal archives)

| Date

|

Names, ages, place of residence of future spouses | Names of witnesses

|

Parents’ names and place of residence

|

Place and date of the marriage notice

|

Signatures of witnesses, bride and groom and the registrar

|

| 14/02/1926

|

Berkowicz Moszek- Nisorz, single, aged 25, resident of Dzialoszyn

Chmura Ruchla Marjem, single, age 23, resident of Wieluń

|

Lajb Kind, knocker-up, aged 74 and Michal Markowicz, knocker-up, aged 63, both residents of Wieluń

|

The son of Icka Majera and Jacheta Berkowicz residents of Dzialoszyn

The daughter of Gabryela and Chaji Mendlewicz residents of Wieluń

|

1-8-15 May, 1926 in the synagogue at Wieluń | M.N BerkowiczR. ChmuraM. MarkowiczL. Kind, registrar Oraczanski Rabin: M. Grunberg |

Bernard’s parents’ marriage certificate, translated from Polish to French by Véronique Chyla

Samuel Berkowicz’s birth certificate (Wielun Municipal archives)

A Wieluń,

On the fifteenth of March nineteen hundred and twenty-nine. Before the registrar appeared Moszek-Nisorz Berkowicz, a dressmaker, twenty-seven years of age, a resident of the Dzialoszyn area of the Jewish faith, living in Wieluń. He arrived in the presence of two witnesses, Michal Markowicz, sixty-six years old and Henoch Dylewski, fifty-eight years old. Both of them work as knocker-up in a synagogue in Wieluń. They arrived with a male child, born in Wieluń, on February twenty-third, nineteen hundred and twenty-nine at ten o’clock in the morning. The child’s mother is named Ruchla Marjem, born Chmura, twenty-seven years old. They decided to name the child Zalma.

This act was read and signed by the witnesses and the registrar as well as the father of the child.

Signatures: Oraczanski Berkowicz Markowicz Dylewski

Samuel Berkowicz’s birth record, translated from Polish to French by Véronique Chyla

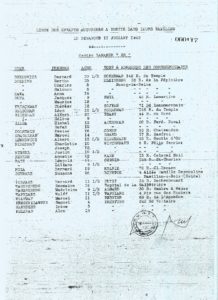

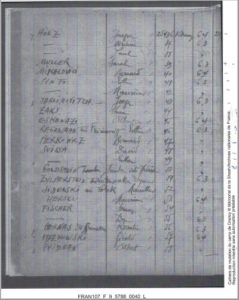

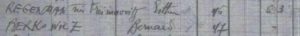

* Documents from the Jewish Center in Montmartre.

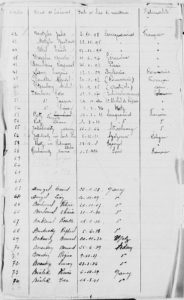

We contacted the Centre Israélite de Montmartre (CIM), the Jewish Center in Montmartre, which currently occupies the premises of the former Lamarck Center. They provided us with copies of the police register which, as from 1941, recorded the entry and departure of the children. They also provided us with a copy of the German propaganda magazine, Signal, which refers to the bombing of the center in April 1944.

Cover of the Lamarck Center police register (from the Jewish Center in Montmartre)

3. BERNARD BERKOWICZ’S LIFE STORY

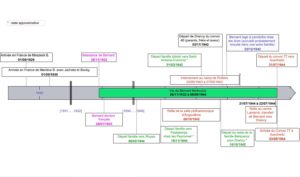

Thanks to all these witness accounts and sources, we were able to piece together the broad outlines of Bernard’s life. To help us find our way, we complied the following family tree. (There is a gap between 1934 and 1939, because we have no information on this period).

* A Polish immigrant family in Metz (1929-1930)

Moszek Berkowicz was born on August 11, 1902 in Dzialoszyn, Poland. In February 1926, he married Mariéna Khmura in Wielun, where she was born on March 15, 1899. The two towns were about 20 miles apart. His residence card tells us that he was a tailor and that he arrived alone in France in August 1929, a few months after the birth of his second child. At first, he lived with his brother-in-law, Moszek Izbicki, his sister’s husband, in Vincentrue.

Mrs. Berkowicz and her two children did not come to Metz until May 1930. Once reunited, the family left the Izbicki’s home and moved house several times before settling at 2, rue des Ecoles in May 1933, a few months after Bernard was born. They stayed there until 1940. The Moselle professional directory of 1936 lists this same address. It was probably there that Moszek had his workshop.

Before migrating to France, the couple must have first lived in Dzialoszyn since it was there that their first child, Jacheta, also called Jeannette, was born on June 9, 1927. Then again, their second child, Zalmann or Samuel, was born on February 23, 1929 in his mother’s native village. His birth certificate mentions that his parents were living in Wielun. We can thus assume that, a few months before her husband planned to leave for France, Mrs. Berkowicz returned to live near her parents. She stayed in Poland for almost ten months with her two young children before joining her husband in Metz in May 1930.

* Bernard, a French child.

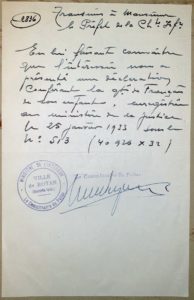

Of the entire Berkowicz family, only Bernard was a French citizen. Having been born in France, he obtained French nationality through a declaration made by his parents according to a law passed in 1927. We tried to obtain his naturalization file from the national archives, but it could not be found. However, in Mrs. Berkowicz’s application for the renewal of her identity card, made in Royan in 1940, she included her son’s certificate of French nationality. She even gave the date of issue (January 25, 1933) and the file number. The fact that Bernard was called up for military service in the French army in 1952 also proves that he was a French citizen.

Bernard Berkowicz’s certificate of French nationality, from Mrs. Berkowicz’s identity card renewal application made in Royan in 1940.

* Life in Metz, which we know very little about (1930-1939)

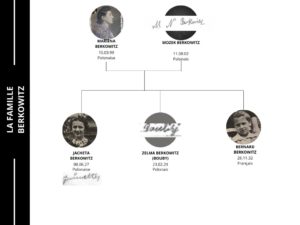

Apart from the administrative details mentioned on the residence card and the reference to Moszek Berkowicz in the Moselle directory of 1936, we know nothing about the family’s life in Metz. We have no family records. As the family tree demonstrates, we have a total of only three photographs of family members.

The Berkowicz family tree, on which we can see that we have no photographs of Moszek and Zelma, just their signatures.

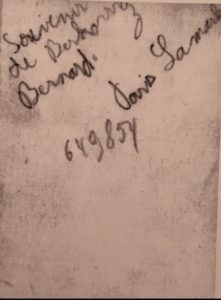

Firstly, there is the photo of Bernard and his sister Jacheta from Serge Klarsfeld’s Mémorial des enfants juifs déportés de France (Memorial to the Jewish children deported from France). In the caption, Serge Klarsfeld states that the photo was given to the Shoah Memorial by Robert Frank. We also have a photo of Mariéna Berkowicz, taken from the application for renewal of her identity card, made in Royan in 1940. Finally, there is the photo that Richard Niderman found in his brother’s belongings. It dates from the period when the children were at the Lamarck Center in Paris. We do not know if the inscription on the back “Souvenir de Berkowicz Bernard Paris Lamarck 649854” was written by Bernard. If so, it is the only trace of his handwriting that we have. As for Moszek Berkowicz, all we have is his signature, and for Samuel, there is only the letter he wrote from Drancy to the Peyronnet family on October 31, 1942.

* A family with three children

Photo of Bernard and Jacheta Berkowicz (from Serge Klarsfeld’s book Mémorial des enfants juifs déportés de France)

The photograph, which was taken in front of the Prefecture in Metz around 1938, shows two smiling children who were clearly close. The eldest daughter of the family, Jacheta, must have helped her mother raise her two brothers, in particular Bernard, who was five years younger than her. It was only while they were in Festalemps that Robert Frank got to know Bernard.

Robert explains that Bernard was “a frail boy, blond, very sweet, serious, always well dressed and clean. The type that is known as an easy child. He often smiled but I don’t remember ever hearing him laugh”. He adds, “He was a blond-haired boy with blue eyes (I think) and a very fair complexion, always smiling, his head slightly tilted to the right side, a sign of a slight shyness… That’s how I remember him, quite vividly.” However, Bernard was three years younger than Robert, so they were not exactly close friends.

By contrast, Robert Frank has more memories of Samuel, Bernard’s older brother, who was a few months older than him. Alice Peyronnet also mentions him in the 2008 audio recording. She speaks of a tall, handsome boy known as Bouby. Robert Frank confirms her words: Samuel “was more developed than me physically and had even won over a girl from the village”. According to Robert Frank, Bouby is an affectionate nickname given to boys by Jewish mothers that can mean “my kitten”. Apparently, everyone called him that and he signed his letter on October 31, 1942 with this nickname.

As for Jacheta, Robert has only a few memories of her. He heard about her after the war from Fernand Peyronnet, who had fallen in love with her, and still felt the same way even after her tragic death.

The parallel journey of the Berkowicz and Izbicki families

Like his brother-in-law, Moszek Berkowicz, Moszek Izbicki was born in Dzialoszyn. Born on 27 November 1896, he married Frajda Berkowicz in 1923. He came to Metz in 1926 with his wife and his first three children. One of his daughters died in 1928. Three more children were born in France. He worked as a cobbler. It was he who welcomed Moszeck Berkowicz into his home in Metz from when he first arrived, in 1929, until his wife and children came to join him. He left Metz for Royan on December 29, 1939 on the 7th convoy of volunteer refugees headed for the Charente. The Berkowiczs joined the Izbickis in February 1940 and they lived, at least temporarily, in the same house, the Villa Fleurette, in the Pontaillac district.

Both families were sent to Festalemps at the same time, in December 1940. However, the Izbickis left Festalemps for the neighboring village of Saint Antoine-Cumond, probably in early 1942, perhaps to find better housing for their large family.

It was in this village that they were arrested as part of the roundup in Angoulême on October 8 and 9, 1942. They met up with the Berkowicz family at the Philharmonic Hall and were deported with them on Convoy no. 40. It seems, however, that some of their five children were not deported at that time.

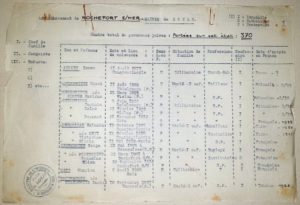

* The departure for Royan (1940)

In September 1939, when World War II was declared, the people of the Moselle region were encouraged to leave. It was considered dangerous to remain there. The Berkowicz family left for Royan on February 6, 1940 in the 12th convoy of voluntary evacuees. The Berkowicz family’s residence card confirms that they left and gives an address in Royan: 1 bis rue du champ aux Oiseaux. In the file for the renewal of Mrs. Berkowicz’s identity card, which she made in the spring, there is another address: the villa Fleurette in the Pontaillac district. This was most likely a villa usually rented out to guests in the summer. Robert Frank confirms that his family also lived in such places. A census of foreign refugees in Royan taken at the request of the German authorities in October 1940 lists 370 Jewish people. A residence record was compiled for each family and signed by the father. These Jewish refugees were not allowed to return to Alsace-Moselle, which by then had been annexed by Germany.

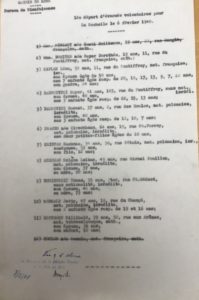

Official record of the 12th convoy of voluntary evacuees to Charente-Inférieure on February 6, 1940 (from a Metz charity organization’s records, Metz Municipal Archives).

Census form for foreigners, October 1940 (Charente-Maritime Departmental Archives).

Déclaration de Moszek Berkowicz lors du recensement des réfugiés juifs le 15 octobre 1940 (Charente-Maritime Departmental Archives)

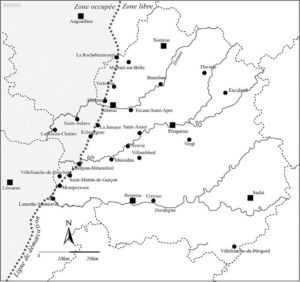

* Departure for Festalemps and life in the village (1940-1942)

The Jewish families who had taken refuge on the Atlantic coast, in particular in Royan, were expelled at the end of 1940. The German occupying forces had forbidden Jews to live in this area. The Berkowicz family was among those who were sent to the occupied Dordogne. They traveled by train and then by truck to the small village of Festalemps, located not far from the demarcation line. They were housed in the Peyronnet family’s farmhouse in Fontaud. The youngest son of the family, Fernand, who was about 20 years old, was of great help to the Jewish families. In fact, with the help of the local teacher, Henri Neyrat, he managed to get three of the ten families living in the village across the demarcation line. He saved their lives. Years later, in 2003, he was awarded the Medal of the Righteous. Robert Frank, incidentally, contributed to this award by giving a testimonial about Fernand’s work.

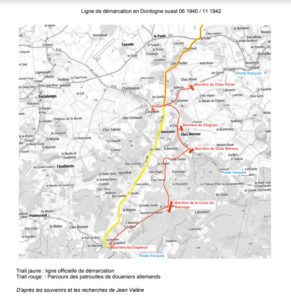

Map of the Dordogne during the war: the area to the west of the demarcation line was assigned to the Charente department at that time. Sud-Ouest newspaper, May 24, 2020

Map of Festalemps and the surrounding area during the war (provided by Mr. Guy Peyronnet, nephew of Fernand Peyronnet)

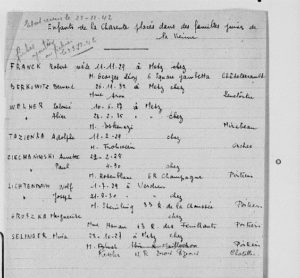

The census forms drawn up at the request of the Prefecture reveal the names of nine other Jewish families from Alsace-Moselle who took refuge in Festalemps between 1940 and October 1942. These families, who did not necessarily know each other beforehand, formed a strong bond between them. Robert Frank remembers evenings when they would get together and play lotto by the light of a “carbide lamp”. The numbers were called in Yiddish. He also recalls a story involving the Berkowicz family: when his mother sent him on a bicycle to take Bernard’s mother a bouquet of lilac blooms that were growing in front of the house, he turned around to check that the flowers were secure on the luggage rack, fell off the bicycle and arrived with the flowers in a very sorry state.

Census of foreigners in Festalemps in 1942 (Dordogne Departmental Archives). The Izbicki family, who had appeared in an earlier census, were now no longer living in Festalemps.

The Jewish families seemed to have integrated well into the community in Festalemps. Robert Frank told us that those two years he spent in the countryside had been very happy for him as a young boy. His father, who had been a farmer in his youth, also enjoyed it. The men and boys helped with the work in the fields. Alice Peyronnet, Fernand’s sister-in-law, with whom the Schuhmann family was staying, said in her testimony that Mrs. Berkowicz was a very good seamstress, who had done work for her several times.

Robert Frank believes, however, that for a lot of adults who had been accustomed to a comfortable life in Metz, it must have been difficult to adapt to the much more rudimentary conditions in the country. Since there was no electricity in the village, it was impossible to listen to the radio, so little was heard about the war and given that there were no Germans in the village, the children lived carefree lives.

Robert’s only painful memory goes back to June 1942 when the Jews, including the school children, were required to wear the yellow star. The teacher, Henri Neyrat, however, forbade the other students to make even the slightest remark to their classmates.

In the letters that Jacheta and Bouby sent to the Peyronnets in October 1942, it is clear that a genuine bond had grown between the two families. The Berkowicz family trusted their hosts completely. We can also see that the young people were well-integrated into the life of the village. They ask for news of each other, send their regards to acquaintances and even send congratulations to a young couple, perhaps when they were getting engaged or expecting a baby.

The commemorative plaque that Robert Frank had put up in the village a few years ago is a final testimony to these relationships.

The memorial plaque in Festalemps.

* The Philharmonic Hall roundup (October 1942)

From 1941 onwards, roundups of Jews increased in frequency throughout France. The largest of them was the Vel d’Hiv roundup that took place in Paris on July 16 and 17, 1942. Many families from Metz who had taken refuge in the Charente region were rounded up in Angoulême during the night of October 8 to 9, 1942. Between 5 and 6 o’clock in the morning, the gendarmes woke up the families and arrested them in their homes. They were allowed one hour to gather their belongings and then a bus then came to pick them up to take them to Angoulême.

In total, 422 Jews (from 22 communities in the Charente and the part of the Dordogne that was attached to the Charente) were arrested and gathered together in the Philharmonic Hall in Angoulême, the intention being to send them to the Drancy camp. The living conditions there were appalling: it was cold, there were no beds and very few chairs. However, when the German authorities began to sort the people into groups, they did not select the French Jews. As a result, Bernard and Robert were released on October 11, 1942, but 387 foreign Jews, including Bernard’s parents, sister and brother, were not. Robert Frank remembers that the fathers of the French children had to accompany them into the courtyard of the Hall. His own father then entrusted him with his wallet, which contained all the money he had left. He shared another vivid memory with us: “Mr. Berkowicz came up to me before I was brutally taken away from my father and said, ‘Robert, you are a big boy. Be careful and take care of my little Bernard.’ Unfortunately, I was not able to protect him and he was deported on Convoy no. 77 on July 31, 1944 and never came back.”

The courtyard of the Philharmonic Hall in Angoulême, bearing plaques commemorating the roundup.

Photo taken by Richard Niderman.

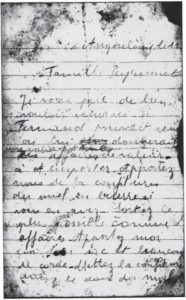

* The letters

The group left Angoulême by train on October 15 and arrived at Drancy the following day, October 16. Most of those arrested were deported to Auschwitz on Convoy no. 40 on November 4, 1942. Of all the people deported on this convoy, only 10 survived. It was during this period that Jacheta and Bouby sent five letters to the Peyronnets. They were written by Jacheta, who signed them Jeannette.

October 11, 1942

“Angoulême, the 11th

Peyronnet family

I would be grateful if you could come here. If Fernand could come, we could give him some valuable things to take with him. Bring us jam, honey, and some butter if you have it. Take as much as you can. Bring me a good bag and lots of string. Put the jam in the honey pot.

We don’t know when we will leave here, so come as soon as possible.

Sending you a big hug.

The Berkowicz family

Make a note of the address :13 rue Fénelon, Angoulême

Let Fernand come as soon as possible, on his bicycle, as fast as he can.”

In this brief letter, written two days after the roundup, Jacheta asks Fernand three times to come by bicycle as soon as possible to bring food and string. She also asks him to come and get the family’s valuables. Her parents may have already foreseen a tragic outcome. Robert Frank tells us that Fernand rode his bicycle the 60 kilometers from Festalemps to Angoulême. After the war, Fernand confided to him that he wanted to get Jacheta out of the room, but she refused to leave her parents. Fernand and Jacheta were in love. The letter of October 31 appears to show the affectionate relationship between them. According to Robert Frank, Fernand never really got over the experience. The letter makes no mention of Bernard, although he was presumably still with his family. Jacheta ends by giving an address, 13 rue Fénelon, which is that of the cathedral presbytery. This may mean that some families were staying somewhere other than the Philharmonic Hall.

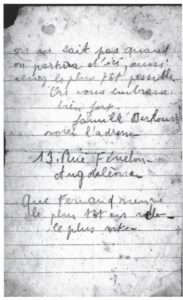

October 15, 1942

“Angoulême the 15 Oct

Dear Peyronnet family, just as we were taking out the luggage, we received your parcel, for which we thank you. It is because of the packing that I am writing you these few lines. We are leaving Bernard with the Red Cross and we are entrusting him to you. You must go to see him often, you will not forget him, I hope. We do not know where we are going. Try to come and see him as often as possible and write to him. I leave you with a big hug. We send our love to Fernand and Roger and the whole household and Gilberte.

from the Berkowicz family, with love”

This second letter, written one week after the roundup, was sent just as the family was preparing to leave for Paris, and thus Drancy. The luggage had indeed been taken out. Jacheta confirms having received a parcel. She thought that Bernard had been entrusted to the Red Cross, probably in fact to Father Le Bideau. She asks the Peyronnets to take care of him, in particular to write to him and to visit him as often as possible. This is evidence of the trust that existed between these two families.

October 16 1942

« Paris, 16th October 1942

Very dear friends

I am writing to you from the station in Paris, we are going to the Drancy camp, in the suburbs of Paris. Say hello to Bernard. Our best regards and warm kisses from all the Berkowicz family.

Sending hugs to you all.”

Jeannette

This note, written from Austerlitz station, mentions that the family is going to the Drancy camp. Jacheta did not seem to be particularly worried. She asks them to say hello to Bernard.

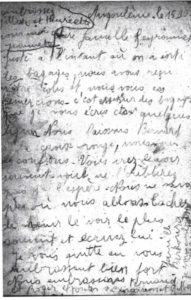

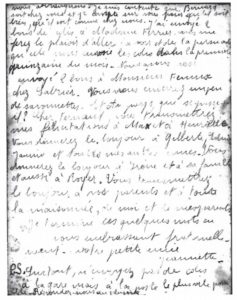

The two letters dated October 31, 1942

Two long letters were sent that day, one by Jacheta and the other by Bouby. The Berkowiczs were not yet aware that they were four days away from leaving for Auschwitz. However, after two weeks in Drancy, their physical and mental health appears to have deteriorated, especially that of Jacheta, and the relatively carefree tone of the first messages has given way to real anxiety.

One letter was written personally from Jacheta to Fernand, and she signed it “Your girlfriend Jeannette”. She also added a note at the end of her brother’s letter to the family.

These letters show that the family was gripped by hunger: the two young people had lost a lot of weight, Jacheta mentioned 20 pounds and feared that they would not be able to hold out for long. While apologizing for being so insistent, they asked the Peyronnets for parcels and enclosed some coupons, pointing out on several occasions that the parcels had to be delivered to the post office rather than to the station in order to reach them. They were also worried about Bernard who was in poor health and suffered from chilblains. It appears that there was a question of his being able to return to Festalemps. On the subject of Bernard, Bouby mentions the “Amélias” that he wrote to and which made his family laugh and cry at the same time. This first name, which was that of Fernand Peyronnet’s mother, no doubt amused the young boy. Behind these simple words, we can sense the fondness for this mischievous child, as well as the feeling of missing him. These last two letters are particularly poignant because they show that the Berkowiczs had only their contact with the Peyronnets to cling on to some sort of normal life. They also show that the Peyronnets were still supporting them as best they could.

The two young people also ask for news of their friends in Festalemps. At the end of her brother’s letter, Jacheta acts as an intermediary for Mr. Helfand, who probably could not write French. He was arrested alone on October 9 and asked for news of his wife, who had escaped the roundup because she was sick. His two children were also spared. However, they had been arrested a few weeks later and deported on Convoy 46.

Whatever you do, don’t send packages to the station, but to the post office.

Drancy, 31.10.1942

My dear friend Fernand,

I received your reply to my letter and you can just imagine how much pleasure it gave me. We had a card from Bernard, and I think it was you who gave it to him when you were visiting him in Angoulême. He told you that he might be going to Fontaud at the end of the week. I would like to know if he is already there or if he’s coming. We have sent you some more coupons for the parcels but it is Saturday and we have not received anything yet. The others are almost all eaten up and we look at them with empty stomachs; I have lost so much weight that almost all my things are too big for me. Also, I am begging you a little and to send us the parcels as soon as you receive the coupons. Send us bread especially, in all the parcels, and at least one parcel with just bread in it. Most importantly, don’t send the parcels to the station, but to the post office, because then they will arrive in two days, whereas we have been waiting for them at the station for over a week, and they aren’t here, because if we have to go without parcels like we are right now, I don’t think I can stand it. Please don’t be angry that we are giving you extra work and hassle, but we thought of you as relatives when we were with you and now even more so, so I will beg you to do so heartily, and when we meet again, which I hope will be soon, we will work something out. I am happy that Bernard is with you and I am counting on you to keep him happy, to make him feel at home. I have sent 2 parcel coupons to Madame Ferrier, I would be glad if you would go to see her and persuade her to send us the parcels dated for the first half of the month. We also sent 2 coupons to Mr. Fenise at Sabrier’s. You must send us a few bars of soap. And in the country, what’s going on? At the Ferraud’s, you must pass on our congratulations to Max and Henriette. You must say hello to Gilberte, Edouard, Janine and all my other friends. Say hello to Irene and her family and also to Roger. You must say hello to your parents and to the whole household, from me and my parents. I end these few words with a fraternal kiss to you – your girlfriend,

Jeannette

PS: Above all, please do not send parcels to the station but to the post office as soon as possible. Reply to us as soon as you can.

Drancy, 31.10 1942

Dear Peyronnet family.

I’m writing you a few words because we don’t always have the opportunity. We are in good health and I hope you are too. We have received your two letters which pleased us greatly. Today is Friday and we do not have any parcels yet but others have already received some. We are counting on you. You are now like our parents because we only have you to help us. Put yourself in our place. I have lost at least 20 pounds and I don’t think I can bear it. Peyronnet family, we are sorry to bother you, but we will make up for it when we get back. For each coupon, we are entitled to 6 1/2 pounds and they put 2 coupons in each letter. One coupon is for 8 days, so the 2 coupons are for 16 days. I understand that we are bothering you because you have work to do but what can we do, we only have you to help us. Thank you in advance and I hope to see the parcels as soon as possible. Bernard wrote us that he might be going to your place due to the diet. He will surely be better off with you. Please take care of him because he is very fragile and gets chilblains on his feet. When he wrote us his famous Amélias, it made us laugh and cry. We thank Fernand very much for his trouble and we would ask you to send the parcels to the post office. I conclude my letter with the hope of seeing you soon. Say hello from all the family. Say hello to all my friends. Thank you in advance and I am counting on you all. Hello to Roger and Renée, Bouby

We have now sent a letter to Ferrier and Sabrier at Fenise because they owe us. I therefore beg you to take care and that these coupons do not get lost. Mainly bread. Please reply.

Hello from the family to Irène.

Dear Fernand,

Mr. Helfand is asking if you have news of his wife, what she is doing and if she is seeing De Birras.

He sends thanks in advance.

Your friend.

If Bernard is not at home, please give him our news.

Jeannette

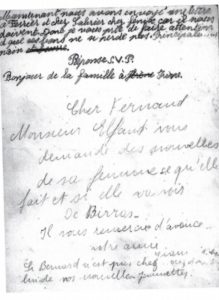

* Bernard in Angoulême and the Vienne department

After having been separated from their families, a number of Jewish boys were taken in by Father Le Bideau. Bernard and Robert stayed for several weeks in barracks where they were treated very well. However, Elie Bloch, the rabbi of Metz, who had taken refuge in Poitiers, wanted the children to be entrusted to French Jewish families so that they could continue to receive a religious education. Thus, on a list kept in the Vienne departmental archives, we see that on December 22, 1942, Bernard Berkowicz was staying with the Aron family in Lencloître. They were a family of four living in a small two-room house (the mother and her two children, as well as her mother-in-law).

List of children placed with Jewish families in Vienne (Vienne Departmental archives)

Photo of the Aron family in front of their house at Lencloître (Shoah Memorial archives)

Nevertheless, Bernard’s time with this family seems to have been very short-lived. Indeed, through some members of the Aron family, Mrs. Evelyne Bloch-Dano and Mr. Fabrice Bloch, we were able to find Mr. Jacques Bichier, a friend of the Aron children with whom he spent a great deal of time. The latter, who still lives in Lencloître, has no memory of Bernard. On his advice, we contacted Mr. Robert Métais, another resident of Lencloître, who is a little older, and he does not remember having seen Bernard either. He must therefore have moved on to another family fairly quickly, presumably on account of the house being so small. However, there are no records to give us any further information about this.

* Bernard’s departure for Paris and the Lamarck Center

The next trace of Bernard is found in May 1943, when, along with the other Jewish children in the Vienne, he was taken to the Poitiers camp before being transferred to Paris and the UGIF centers.

On May 20, 1943, Mr. Zwick, an SS-Untersturmführer (second lieutenant), informed the police in Poitiers that a convoy of 70 Jewish children was to be taken to Paris to centers run by the UGIF (Union Générale des Israelites de France, or Union of French Jews). This organization was created in November 1941 by the Vichy government at the request of the Germans. It represented the Jews and undertook social activities such as paying allowances to households with no income, or funding canteens and hospices. It actively participated in the massive census of Jews in France, which helped the Gestapo to organize many of the roundups in France between 1941 and 1944.

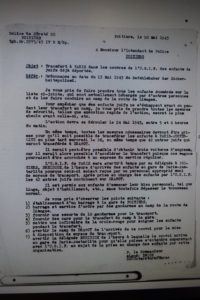

Letter dated May 20, 1943, from Mr. Zwick to the police superintendent in Poitiers (Vienne Departmental archives)

On May 24, 1943, Bernard Berkowicz and Robert Frank were sent to the concentration camp on the road to Limoges, in Poitiers. This camp had been housing Jews since July 1941. In most cases, the internees were transferred from there to Drancy.

An extract from the Poitiers camp register dated May 24, 1943. (Vienne Departmental archives)

On May 26, 1943, these same children left the camp, headed for Austerlitz station in Paris. They were then transferred to the Lamarck center, a UGIF center at the foot of the Sacré Coeur in Montmartre in the 18th district in the north of Paris. It was one of the many UGIF centers that took in children after the great roundups of 1942.

In these centers there were children who were “free”, having been placed there by their parents, others who were considered “abandoned” for various reasons, as was the case with Bernard, and also children who were “blocked” or segregated, who the Germans had interned, liberated from the camps and then placed in the care of the UGIF. Such foreign children, or those born of foreign parents, were kept on file and “subject to deportation” at any moment.

Letter from Mr. Kahn, the manager of the Lamarck center, to the chief of supplies of the 18th district on May 27, 1943. He asked for food coupons to feed the children who had just arrived. He provided a list of names. (Shoah Memorial archives).

According to the Lamarck center’s admissions list, Bernard was assigned number the 905. Robert Frank, on the other hand, was soon transferred to another home, rue des Rosiers. True to the promise he had made to Bernard’s father in the courtyard of the Philharmonic Hall, he went to see Bernard regularly. However, when he was extricated from the UGIF home in February 1944, and became a “hidden” child, he was no longer able to keep his promise. Even now, 80 years later, this remains a painful memory for him.

In June and July 1943, Bernard was included several times on lists of children authorized to go out on Sundays with Jewish families who had volunteered to host them. These Sunday outings allowed the children to experience a family atmosphere and the Lamarck center to reduce its food expenses. On each of these outings, he went with a boy called Léon Gelbchar who was probably one of his friends. Joseph Niderman was no doubt another of his friends, since it is through him that we have the portrait of Bernard that appears at the top of this biography and again here.

Photo of Bernard Berkowic, possibly with his inscription on the back, found by Richard Niderman among the belongings of his brother, Joseph

Robert Frank says of this photo: “I am gripped by this photo. It is not the image I have of him. The very contrasting light and shade, the dark eyes, the thoughtful and serious face is not that of Bernard at 13 years old… It must be said, however, that I did not see him in the last six months before he was deported.”

List of children allowed to leave the Lamarck center on Sunday July 11, 1943 (Shoah Memorial archives)

One of the UGIF lists mentions that Bernard returned to the center on September 29, 1943 after a stay at the center in La Varenne, which was a home that belonged to a Jewish community called “Beiss Yessoïmim”, meaning “the orphans’ house”. It was in St-Maur-les-Fossés, which was in the country at the time. Bernard and the other children were most likely sent there to give them a chance to get out into the fresh air to “recover” after the ordeals they had recently experienced. Bernard probably stayed there on the same dates as Charlotte Brzezinski, another child from Metz, between August 11 and September 29.

Lamarck Center record of arrivals and departures on September 29, 1943. (Shoah Memorial archives)

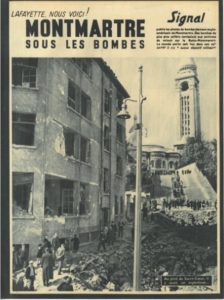

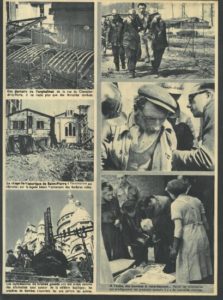

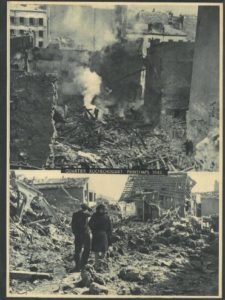

There is one incident, which would have been traumatic for anyone, that must be mentioned. Bernard Berkowicz was among the children at the Lamarck Center on April 20, 1944, when the building was partially destroyed by an Allied bombing raid that was targeting the La Chapelle railroad yard.

Robert Frank explains more about this bombing: “I have always heard the following version: during an American bombing over Paris, an aircraft was hit but the pilot was just able to keep control of his plane and drop two bombs in the street that runs along one side of the Lamarck home before crashing further down the street. The adjacent houses were not destroyed but damaged by the blast of the bombs, which made huge holes in the street. The pilot died at the bottom of the street after having avoided what would have been a disaster had he come down on the houses with the two bombs still on board the plane.

Extracts from the magazine Signal, a Nazi propaganda newspaper, dating from the spring of 1944

Note the cynical way in which the newspaper condemns the brutality of the Allies who bombed the Jewish orphanage. They even show a photo of a bed. (Montmartre Jewish Center Archives)

The children were then transferred to the Lucien de Hirsch school at 71 avenue Sécrétan in the 19th district, where they went to school. This was the oldest Jewish school in Paris and, like the Lamarck Center, it was run by the UGIF.

* The roundup on July 21-22, 1944.

On the night of July 21-22, 1944, the De Hirsch school, along with all the other UGIF centers, was the target of a large roundup ordered by Alois Brunner, Eichmann’s right-hand man, who was in charge of Drancy camp. At dawn, 71 children and 11 teachers were arrested, loaded onto Parisian buses and taken to Drancy.

The De Hirsch school sent us a poignant letter written by a Mr. Monteil, a former resident of the neighborhood, during the Barbie trial in 1986. As a poor and miserable child on that July morning in 1944, Mr. Monteil envied those well-dressed children who appeared to be heading to the countryside for a happy and joyful day out. “How could I have guessed where these “privileged ones” were going?” Even though his account differs a little from that of surviving children (he speaks of German trucks rather than Parisian buses with rear platforms), Daniel Urbejtel confirms that the children were “dressed in new clothes and carrying bundles of new clothes, giving the impression that we were going on vacation, which seemed to bode well, except that for us, it did not.”

Somewhat paradoxically, it was the brutality of an officer who humiliated a 12-year-old boy in public that led to his being saved.

Letter written by M. Monteil to the Lucien-de-Hirsch school at the time of the Barbie trial

* Internment in Drancy camp (July 22-31; 1944)

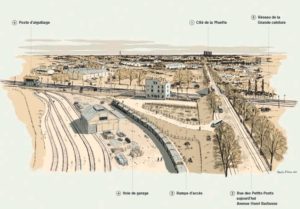

Drancy camp, based in a housing estate called the Cité de la Muette, was the main internment and assembly center for Jewish victims of the Holocaust. 67,000 of the 75,000 Jews deported from France were interned there.

Andrée Warlin, who was interned in the camp at the time, recalls that it was a clear, starry night when she saw the buses carrying the new arrivals pull in. She and the other internees were alarmed when they heard the bubbling, chattering voices of little children, including Bernard, who were alone and without a father or mother.

Bernard was assigned the number 47 and was placed in room 3, on stairwell 6. Together with everyone else who was rounded up, he remained there until July 31, 1944.

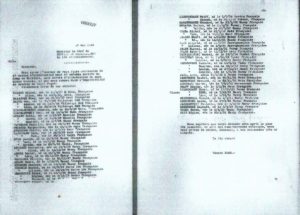

Extracts from the Drancy camp transfer register (Shoah Memorial archives)

* The departure of Convoy 77

According to the testimony of Yvette Levy, a survivor of Convoy 77, and also some other returnees from the camps, the unknown destination they were going to was known as “Pitchipoï”, a Yiddish word that was used to refer to a small, imaginary world. They thought they were going to a concentration camp in Germany.

Also, the night before the departure, the internees prepared their bundles and did not sleep in their usual rooms but on the stairwells. Then, on the day of departure, they were “parked” in the courtyard, which was off-limits to other inmates, while waiting to board the buses (of which there could be up to 50), which were waiting behind the camp gate, ready take them to Bobigny railroad station. Convoy 77 left Drancy early in the morning. There were 1300 people on board. Among them, there was a baby, which had been born in Drancy, in a cardboard box that served as a cradle.

People were in a good mood, many of them singing, on the journey from Drancy to Bobigny. When they arrived at the station, they grabbed their bundles, without really knowing whose was whose, since everything was done in such a hurry, and then stumbled down the embankment and climbed straight into the cattle cars. The guards were quite kind at that point, in that they offered to help the deportees get on the train.

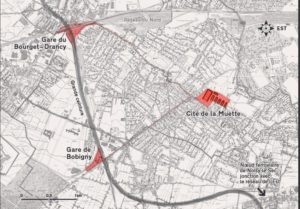

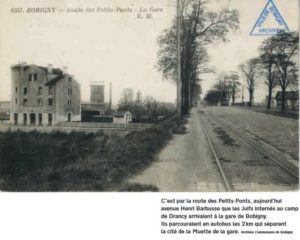

Bobigny was the nearest train station to the camp, at just over a mile away. The Nazis used it from July 1943 until August 1944, at which time it took over from the one at Le Bourget-Drancy, to deport most of the Jews arrested in France from Drancy to Auschwitz.

In total, 21 convoys left from Bobigny, deporting 22,500 people.

The following documents, from the Bobigny deportation station website, explain the situation in more detail.

Map showing the location of the Cité de la Muette in relation to Bobigny station.

Photo of the Route des Petits-Ponts

Overview of the Drancy-Bobigny site, showing the various areas involved in the deportation.

The children were loaded in groups of 60 in each car, while the teenagers, women, men and old people were in larger groups of about 100 per car. They were therefore very tightly packed in and it was also very hot. All they had in the way of facilities were two buckets: one with drinking water, the other serving as a lavatory.

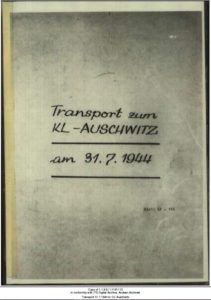

On July 31, 1944, Convoy 77 left for the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp.

![]()

The Convoy 77 departure register (Arolsen Archives)

The convoy arrived at Auschwitz on August 3, 1944. The exit from the train was, unlike the boarding, much more abrupt. The SS shouted at and beat deportees. On arrival, as the camp was both a concentration camp and a killing center, the deportees were separated into two groups: a line on the left, to which most of the women, the children and the elderly people were sent, and a line on the right, for men and women capable of working. This was known as the selection process.

Map showing the route taken by Convoy 77

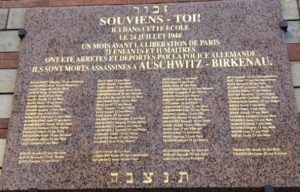

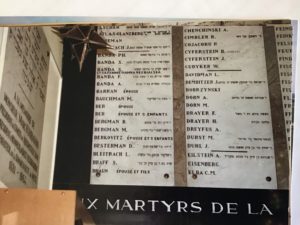

According to the French Official Gazette, Bernard died on August 5, 1944. He was then 12 years old. His name appears on the commemorative plaque at the Lucien De Hirsch School. The name of the Berkowicz family is also inscribed on the commemorative plaque at the Polish synagogue in Metz.

The commemorative plaque on the wall of the Lucien De Hirsch school

Commemorative plaque at the Polish synagogue in Metz: the Berkowicz family is listed, but only two of their children are mentioned (Photo provided by Henry Schumann)

In addition to the witnesses mentioned at the beginning of the biography, we would like to express our warmest thanks to all those who offered their support, in particular Ms. Isabelle Salvy and Mr. Jean-Michel Supervie in Charente-Maritime and Mr. Henry Schumann in Metz, as well as to the numerous communal, departmental and national archives services that we contacted.

Contributor(s)

This biography was produced by the 4th class of 12th grade students at the Louis Vincent de Metz high school, under the guidance of their history and geography teacher, Mr. Mandaroux, and the teacher and librarian, Ms. Michel.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Quel magnifique travail de recherches.

Un très grand et très sincère bravo !

Restituer la mémoire des déportés est le meilleurs hommage que l’on puisse leur rendre.

Contribuer ainsi à perpétuer leur biographie est une contribution, certes modeste, mais oh combien importante pour l’histoire de la Shoah.

J’y découvre de surcroît le CIM dont j’ignorais l’existence.

Merci aux élèves et à leurs profs.

RL

Superbe travail de recherche et d’écriture.

Un point important : des femmes aussi ont été sélectionnées pour entrer dans le camp pour travailler, dont Yvette Lévy, que vous évoquez dans cette belle biographie.