The one-way journey of Abraham Albert BOCARRA [ or Boucara]

by Danielle Laguillon Hentati

Honorary professor of Italian and author honored with the Palmes Académiques

“Don’t you think it really should be told?

“But there’s nothing to tell, old man. A hundred guys in a cattle car. A trip that goes on day after day, night after night. Old people who lose it and start screaming. I don’t see what there is to tell.”

“And at the end of the line?” I ask him.[1]

Introduction

The twentieth century will always be branded in history by the deportations to the camps of Nazi Germany.

But what exactly is a deportation? The first definition, in its dictionary meaning, stresses the point of departure, but there is nothing obvious about that insofar as the point of arrival changes the sense.

This definition of forced transportation out of a territory makes no sense once it is realized how huge and horrible are the conditions suffered by the deportees on arrival. Viewed apart from the rest of the war, the horror appears as a separate goal programed by the Nazis. Attention is focused there rather than on the beginning of the processes that led to the camps, how the repression took place in France. The point of arrival, what the deportees lived through thereafter, largely erases the point of departure.[2]

Memory and the testimony of the survivors also reinforce the direction of this linguistic transformation by tending to recount the concentration camp experience.

We will therefore emphasize here who Abraham Albert Boucara was [3], one who “never returned”[4] among millions of others, and relate the life of a quiet man wiped out by the murderous insanity of the Nazi state.

Family milieu

Abraham Albert Boucara was born on July 14, 1894 in Tunis, Tunisia into a well-to-do Jewish family. Natives of Constantinople, his grandfather Eliaou and his father Judas, both traders, settled in Tunis in 1877. They were given French citizenship in Algeria by the Crémieux Decree.[5]

Around 1879 Judas married Semha, the daughter of a master glazier, Jacob Mendès Ossona [6].

At Abraham Albert’s birth his father, an antique dealer well-known in the medina, lived with his family at n° 62 rue de Marseille, in the brand-new “European” neighborhood, so called to differentiate it from the medina; Abraham Albert was the youngest child of the family, which included Élie Lalou, born in 1881, Jacob Jacques in 1883, Émilie in 1887, Rachel in 1890, and Dario in 1893.

The Boucara/Boccara and Mendès Ossona families belonged to what is known as the “Portuguese nation” or L’Grana, as opposed to the Twansa, who were Tunisian Jews.

The Portuguese Jewish community in Tunis, called L’Grana, is a unique case. Its founders, who came from Portugal, first made up an oligarchy within the Jewish community of Leghorn, Italy. Starting in the middle of the 17th century the Leghorn Portuguese merchants opened trading posts in Tunis. There arose little by little and at first informally, a “Jewish Leghorn nation of Tunis”, soon to be followed in 1710 by the official establishment of a qahal qadosh (congregational unit). Despite their emigration to Leghorn and Tunis these Jews long remained imbued with their Portuguese culture that distinguished them from the indigenous Tunisian Jews, known as Twansa.[7]

They were strongly set apart from the native Jews by their Europeanization (Italian and/or French language, costume, endogamic marriage). They had their own rites, synagogues, celebrants, rabbis and cemeteries and considered themselves the flower of the European bourgeoisie. They were in fact part of the elite of the country.

Their children studied and then traveled. Jacob Jacques thus found himself in London in 1908 and in Turin in 1911 with Élie. The sons did their military service and were mobilized during World War I[8]. After the war Élie, Jacob Jacques and Abraham Albert settled in Lyon, while continuing to travel on business.

Abraham Albert was a merchant when he married[9] Emilia, the daughter of Aron Domanovicz and Sara Rszewska, a Polish family from Turek that was established in Strasburg.

At that time there were no paid vacations and organized travel; the expositions provided a large view of the world and the taste of exotic fruits. These were the roaring twenties, the reprieve between war and depression. The French discovered their colonies by visiting the colonial expositions. In three generations the Boccaras went from being active merchants, with Eliaou journeying to procure or to sell at the risk of his life, to his grandchildren exhibiting in reconstituted souks with visitors riding on camels [10].

Business was good; like his brothers he continued climbing the social ladder to become a carpet broker[11]. He seems to have had a rather discreet, introverted personality. His niece remembers him only to mention that his daughters, Simone Sonia (1927 – 1955) and Yolande (1928 – 2005), were brought up in Tunis after their parents’ divorce. Abraham Albert never remarried and lived by himself in Lyon.

Anti-Semitism and race laws

In the 1930’s the political climate became more extreme with Hitler’s accession to power. The Other was stigmatized, while racial hate and especially anti-Semitism poisoned the relationships between both adults and children.

When did it all start? Why? During recess Robert and I were suddenly surrounded by a group of girls who danced around us chanting:

“Oh, la Jewess! Oh, la Jewess! Oh, la Jewess!”

I was speechless, overwhelmed. Jewess? What did that mean? Never heard the word! I felt like crying. And the dance turned around us, pitiless, with the same chant:

“Oh, la Jewess! Oh, la Jewess! Oh, la Jewess!”

I squeezed Robert’s hand very tightly. We didn’t cry. We didn’t budge. I stood up very straight like Papa told me. What had I done? Why did they reject me? Why did they hate me ?[12]

Domestically and internationally the political situation got ever more tense. Still, many thought the war would be avoided thanks to the Munich agreements. But on September 1, 1939 following the German attack against Poland, general mobilization was decided in France, applicable as of the 2nd; the border with Germany was closed, and the inhabitants of the border zone, notably the people of Strasbourg, were evacuated. At 5:00 p.m. on September 3, 1939 France declared war on Germany.

While several members of the family went back to Tunisia, Abraham Albert still felt safe in Lyon and persuaded himself that the downturn in business was temporary. Few people in wartime think about buying carpets. He no doubt presumed, like most of the French, that the Maginot Line would protect them. In the streets, as at the front, was heard the song:

“We’re gonna hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line

Have you any dirty washing, Mother dear?

We’re gonna hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line

Cause the washing day is here.

Whether the weather may be wet or fine

We’ll just rub along without a care.

We’re gonna hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line

If the Siegfried Line’s still there.”[13]

But the “phony war” had a bitter taste to it; it ended with the signing of the armistice on June 22, 1940; the French, though humiliated by the defeat, had confidence in Pétain. After the division of France, Lyon found itself in the Free Zone. “Gradually the trains started rolling again, the refugees went back to their homes, and mail service returned. A kind of order was reestablished“[14]

Pétain then set up a government of collaboration with the enemy, which was to be based on the laws promulgated between October 1940 and February 1944, beginning with the Statute on the Jews decreed on October 3, 1940, setting them apart from the rest of the population.

Front page of the newspaper Le Matin of October19, 1940,

announcing the promulgation of the Statute on the Jews.[15]

And yet, despite this segregation Abraham Albert trusted the Maréchal and the French, a civilized people educated in the schools of the Republic, their hearts and minds filled with the motto “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”. Even after the abrogation of the Crémieux Decree which took away his citizenship[16], he still did not think about leaving Lyon to join his daughters in Tunis. At any rate, the Statute on the Jews[17] was enforced in the Regency of Tunis.

There is nothing to reveal his precise state of mind, but the facts show that he stayed in Lyon. Was he too trustful? Or rather downhearted, too crushed to react?

The armistice having instituted a semblance of peace, life and business gradually took up again. But it was only a sham; in reality a barrage of laws reduced Jewish freedom more and more, including the freedom to work and to study. The law of June 2, 1941 even instituted a second Vichy Statute on the Jews, buttressed by the decree of July 1941, which excluded Jews from all commercial and industrial professions. In addition, this statute authorized the prefects to carry out administrative internment of Jews holding French citizenship. Didn’t Abraham Albert and his brothers sense the danger? Were they naïve, blinded by the Maréchal’s personality?

For a long time I failed to understand the passive attitude of the majority of French Jews faced with Nazi persecution. While researching my book, Le Fusil d’Eliaou, I came across the Crémieux Decree and the dazzled gratitude of the Algerian Jews, who went from the condition of second-rate subjects to French citizenship in 1870. The Revolution had granted citizenship to the Jews of Alsace and Lorraine in 1793. A good number of their descendants ended up at Auschwitz-Birkenau for their faithfulness to France.[18]

On July 14, 1942 his nephew Jean was arrested in Lyon and then released two weeks later. What Abraham Albert considered just an incident was only the beginning. Shortly thereafter he heard the rumor that roundups had begun in Paris, before being extended to other cities.

A thunderbolt struck on November 8, 1942. The Allies landed in Algeria and Morocco. French North Africa became the theater of major military operations that marked a turning point in World War II. The Nazi authorities reacted by occupying the Free Zone in France and creating a bridgehead in Tunisia to support the Afrikacorps that was retreating over the Libyan desert. The landing of the Axis army plunged Tunisia into disarray and disrupted daily life. As soon as they arrived the Axis troops set up in requisitioned premises in the center of the capital, while the Gestapo started hunting down Communists, Freemasons and Jews. In addition to the premises the German and Italian troops began to confiscate property and food commodities, demanded ransoms from the Jewish community, and finally announced the internment of Jewish workers in camps[19]. Moreover, repressive deportation (of resistance fighters, political activists, hostages…) was set in motion from Tunisia[20] to the Nazi camps in Europe.

Did Abraham Albert then understand that it was too late to get out? Perhaps he was convinced the Allies wouldn’t be long in landing in France to liberate the country…But the vise was tightening. The word “Jew” was stamped on I.D. and rationing cards. It was a degrading word that pointed them out to the enemy.

The situation got worse. The sabotage carried out by the Resistance movement called forth reprisals: arrests, executions, deportations.

His brothers

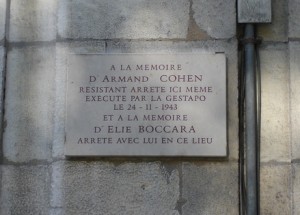

On November 20, 1943 his elder brother Élie[21] was arrested by the Gestapo at his home in Lyon for “anti-German activity”[22], along with his brother-in-law, Armand Cohen. Élie was deported to the Swietochlowice camp in convoy n° 63 and did not return.

As for Armand, he was tortured for committing acts of resistance and shot on November 24, 1943 in the cellars of Lyon’s École de la Santé.

Commemorative plaque on the wall of their building in Lyon[23]

Their wives managed to flee through the little courtyards with their children and were hidden by Mathilde Khenaffou[24]. About a month later one of Charles Khenaffou’s colleagues found them a hideout at La Chapelle-sous-Chanéac (Ardèche department), where they lived with Mathilde until the Liberation. Charles, meanwhile, was being hunted and remained hidden.

The rest of the family was not spared. On May 2, 1944 it was Jacques Jacob’s turn to be arrested with two of his children, Simone and Henri. They died in deportation.

|

|

Abraham Albert “never returned”

In 1944 Abraham Albert lived at n° 9 rue Neyret in the heart of the Croix Rousse heights in Lyon’s First district. He was arrested there on June 26, 1944[25] because he was a Jew, even though no reason for arrest was indicated. Like his brothers before him he was detained in the “Jews’ huts” at Lyon’s Montluc military prison, sadly famous for its role as a detention center during World War II. More than 9,000 people, including Jean Moulin and Marc Bloch passed through the place between February 1943 and August 1944[26]. He no doubt found neighbors and acquaintances there, but did he even feel like talking? Or did he stay huddled up in a corner, mute and broken?

He was transferred a few days later[27] to Drancy and interned with the I.D. number 24.769, according to the files on the camp’s “Israelites”. He was to spend two months there in appalling conditions of crowding, lack of hygiene, hunger and thirst.

Then he was deported to Auschwitz in convoy number 77 that left from Drancy on July 31, 1944. Abraham Albert died on August 5, 1944 at the Auschwitz extermination camp[28].

Abraham Albert disappeared without a trace. No body. No grave.

In 1948, however, a friend and neighbor — a certain Monsieur Thiey — who lived at n° 39 rue Neyret, announced that he was looking for him. Then his daughters, Simone and Yolande, back from Tunis and living in Paris, undertook a long process beginning with a “Request for the regularization of the civil status of a “person never returned” on April 19, 1952. After two years of enquiry and verification the administration issued an act of disappearance on April 2, 1954. But his daughter Simone died in 1955, and Yolande married an American and went to live in Washington.

As long as the death of a deportee is not officially recognized and registered, their families can neither settle the estate nor file a dossier to give the deceased a status, making it possible for the family to have its rights recognized. Yolande thus retriggered the procedure to obtain the mention “Died in deportation” on her father’s death certificate, but she passed away in 2005. The act was finally drawn up in Paris on December 17, 2009 and transcribed on October 12, 2010 by an agent of the Civil Status bureau of the Town Hall of Lyon’s 1st district.

Beyond Abraham Albert Boucara’s file there appear broken lives, tragic, moving destinies,

[1] Jorge Semprun, Le grand voyage. Gallimard, 1963, p.30.

[2] Thomas Fontaine. Déporter. Politiques de déportation et répression en France occupée. 1940-1944.

Histoire. Université Panthéon-Sorbonne – Paris I, 2013, p.9. Français. <NNT : 2013PA010602>. <tel-01325232>

[3] DAVCC, Dossier Déporté Politique 21 P 481 725.

[4] These are the deportees about whom nothing is known after the war’s end; the administration classifies them in a special category under the heading “Never Returned” [Non Rentrés].

[5] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, Collection Témoignages de la Shoah, Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah, Editions Le Manuscrit, 2006, p.72.

[6] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.72.

[7] Grana. La communauté juive portugaise de Tunis d’après ses ketubot[Grana. The Portuguese Jewish community according to its marriage contracts:]

[8] Élie: Bouches-du-Rhône Departmental Archives, recruitment in Marseille, class 1901, enlistment record n°892 bis ; Jacques Jacob : ANOM, recruitment in Constantine, class 1903, enlistment record n°837. Abraham Albert’s enlistment record was not found, but his niece Mireille writes that he was “so proud of being a veteran”. Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.210.

[9] Extract n°184 from the Strasburg Town Hall’s register of marriage licenses

[10] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.73

[11] Death certificate n°118.

[12] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.46.

[13] We’re Going to Hang out the Washing on the Siegfried Line is an Irish song sung during Word War II in Europe after 1939. With the French lyrics by Paul Misraki, this song, interpreted by Ray Ventura and his pupils was quite successful.

[14] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.105.

[15]https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lois_sur_le_statut_des_Juifs_du_r%C3%A9gime_de_Vichy#/media/File:Le_statut_des_Juifs_est_promulgu%C3%A9_-_Le_Matin.jpg

[16] Loi du 7 octobre 1940.

[17] As specified in Article 9 of this decree, the anti-Semitic laws were to be enforced in the colonies and protectorates.

[18] Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.121.

[19] Danielle Laguillon Hentati, « Les camps oubliés de la Tunisie (Décembre 1942 – mai 1943) ». Paper given on March 1, 2018 in Sousse (Tunisia) at the 4th training session in connection with the exhibition on “L’Etat trompeur : le pouvoir de la propagande nazie” [The Deceitful State: The Power of Nazi Propaganda], organized by the Laboratoire du Patrimoine de la Faculté des Lettres, Arts et Humanités of La Manouba (Tunisia).

[20] Danielle Laguillon Hentati, « La mémoire des déportations de Tunisie (1940 – 1943) : de l’oubli à l’histoire ? » Paper read on May 19, 2018 at the 6th seminar of Professor Habib Kazdghli’s graduate school at the Faculté des Lettres, Humanités et Arts of La Manouba (Tunisia); Mémoires de déportation. Des geôles de Tunis aux camps nazis. Work in progress.

[21] Portrait in Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.127.

[22] Dossier n°1156 of Lyon’s Montluc prison

[23]https://www.geneanet.org/gallery/?action=detail&id=130932&individu_filter=COHEN&rubrique=monuments

[24] Lucienne Mathilde Burdin, the wife of Charles Khenaffou. On June 30, 1991 the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem awarded Mathilde Khenaffou the distinction of Righteous among the Nations.

http://www.ajpn.org/juste-Mathilde-Khenaffou-1535.html

Likewise, Julien Azario, who supplied them with “genuine false papers” that saved their lives, received the Medal of the Righteous. Mireille Boccara, Vies interdites, p.213-214.

[25] Rhône Departmental Archives on line, Prison de Montluc, dossier n°5428, 2 pages.

[26] Thanks to the efforts of Prefect Jacques Gérault and several associations, among which Lyon’s Association of the Survivors of Montluc, a large part of the Montluc prison is inscribed as a historical monument and transformed into a Memorial to the Internment by the Vichy regime and the German Authorities during the 1940-1944 Occupation, and open to the public. Sources : https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prison_Montluc; and http://www.espacestemps.net/articles/de-la-prison-montluc-au-memorial-et-apres/

[27] On June 30, 1944 or July 3, 1944 according to the DAVCC file; On July 1, 1944 according to the Montluc prison file

[28] Death certificate n°118.

Français

Français Polski

Polski