Arthur KREINDEL

An Austrian Jew and Communist who was deported to Auschwitz

————————————————————————————————

————————————————————————————————

Arthur was born in Vienna, in Austria, on June 27, 1916.

His father, Elias Kreindel, was born in Krakow in 1879 and his mother Rosa, née Gerowicz, in Vienna in 1889.

Arthur, who had two brothers and one sister, was the oldest child in the family.

He trained to be a furrier. He also joined a Communist Youth organsiation (Kommunistischer Jugendverband, KJV), where he met his girlfriend, Vilma.

A little about Vilma, through whom we have received most of this information[1].

Vilma Steindling, née Vilma Geiringer, was born in 1919 into very poor Jewish family. She was only 3 years old when her father died and 8 years old when her mother became seriously ill. Her mother had to be hospitalized for several years and died when Vilma was 13. At the age of 8, Vilma was sent to the Jewish orphanage in the 19th district of Vienna. When she was just 14, she began an apprenticeship as a milliner and lived in a Jewish home for apprentices in the 2nd district.

She soon felt that she needed to get involved in social issues and at the age of 15 she joined a Communist Youth organization the Kommunistischer Jugendverband, where she met her future partner Arthur Kreindel, who was 3 years her senior[2].

In 1933 Austrian fascists banned the Austrian Communist Party, the KPÖ, and the resulting oppression prompted Arthur to leave Vienna for Paris, where he continued his trade in a workshop at 24, rue d’Enghien, in the 10th district of Paris. He lived at 31, rue Bergère, in the 9th district3].

Vilma, after finishing her apprenticeship as a milliner, joined Arthur in the autumn of 1937, a few months before the Anschluss (the annexation of Austria by Germany). It would seem that he was then living in the 10th arrondissement, at 13 rue du Château d’eau[4].

As the persecution of the Jews in Austria became intolerable, Arthur ensured that visas were arranged for his parents, brothers and sister, so that they could go to Paraguay. This they did, and from there crossed the border in secret and settled in Argentina. His family left Vienna for Paris on the eve of the “Kristallnacht“[5].

On September 1, 1939, Germany invaded Poland , and war broke out.

In France, a country with a tradition of immigration, admission requirements changed. On April 10, 1938, radicals and conservatives brought Édouard Daladier to power. His Minister of the Interior, Albert Sarraut, implemented a policy that imposed stricter legislation on the policing of foreigners. The outbreak of war led to the arrest of many of them on suspicion of being members of the Fifth Column or deemed to be enemies, when in fact they were communists or socialists and anti-Nazis. The authorities could thus justify such drastic measures as official internment[6].

It would appear that Arthur, along with other Austrian refugees, was interned at the Colombes stadium, north west of Paris.

Vilma left Paris for Grisolles in the Tarn et Garonne department of France, in a group of other young men and women. There she spent the spring, summer and autumn of 1940, only to return to Paris when Arthur had been freed.

From 1942 onwards, they lived in the Paris suburbs and were actively involved in the resistance movement. Together with other Austrian women, Vilma joined the “Mädelarbeit”, the German Labor or rather anti-German Labor movement. The young women members approached German soldiers to try to persuade them of the absurdity of the war and to advise them to desert, because the war could not be won anymore. This was a very dangerous occupation, since the women were in danger of being reported.

This is what happened to Vilma, who was the first of her group that this happened to. One day, during a second meeting with a German soldier, two German policemen arrived, arrested Vilma and took her to Fresnes prison. Three months later, she appeared in court and was sentenced to five years in prison. She was then held for another three months at Fort de Romainville, and transferred to La Petite Roquette.

In early August 1943, she was transferred to the Drancy camp and then, on October 2, 1943. deported to Auschwitz on convoy no. 59. On arrival, she was selected to work and her arm was tattooed with the number 58337[7].

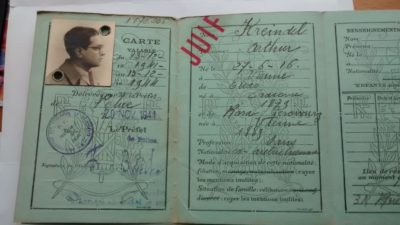

Arthur, meanwhile, was issued with an identity document (No. 59AS63938), known as the “foreigners’ card”, on November 20, 1941. This is a 19-page booklet, on the cover page of which is written: “Non travailleur”, meaning “Not a worker”. The following pages include a side-shot photo of Arthur and his personal details. Stamped in red ink and in capital letters is the word “JUIF”, or “JEW”. Arthur’s address is given as 31, rue Bergère, Paris[8].

Around this time, the trail goes cold and there are some grey areas. A document from the Direction Centrale de Renseignements Généraux (General Intelligence Directorate) and the Direction des Etrangers et des Affaires Juives (Department of Foreigners and Jewish affairs) in Paris, dated March 17, 1943, states that Arthur “would have been living in the free zone since January or February 1941”. This document also states that Arthur had not been working since June 1940 and that he “has not been in compliance with the law of 2 June 1941”, despite the fact that he was still listed in the Commercial Register under the number 688069.

In addition, a document provided by members of Arthur’s family tells us that in December 1944, his father, Elias, wrote to the company that owned the newspaper “l’Auto” (the predecessor of the newspaper “L’Equipe”), at 10, rue du Faubourg, in Montmartre, Paris, in an attempt to locate his son. An “administrator” informed him that Arthur had left the premises, located at the newspaper’s address, which he had previously occupied and for which he had given notice to leave on June 27, 1943.

It is worth recalling here the Vichy laws concerning the status of Jews and the census of the Jewish population, signed by Marshall Pétain.

While the Vichy “first law on the Jews”, in October 1940, excluded Jews from the civil service, in particular the senior civil service and important State bodies, from being officers in the three armies, and from the judiciary and education, the law of May 1941 extended these professional bans. In addition to the prohibition on being directors of publishing, film, theatre and radio companies, a policy of quotas limiting the number of Jews in independent professions was also introduced. The second statute increased the list of banned professions and provided for a restriction in principle on access to a “liberal profession [doctors, artists, writers etc.], a commercial, industrial or artisanal profession, or a freelance profession”. According to the Minister of Justice, Joseph Barthélémy, it was a question of prohibiting Jews from holding “the position of a director at the very soul of France or serving the interests of France”.

In June 1941, the first reference was made to the “right of the Prefect to order internment in a specialised camp, even if the person concerned is French”.

The effect of these laws was to prevent Arthur from working. According to the Department of Foreigners and Jewish affairs records, Arthur should have presented himself or been “taken to the Jewish Service” to be registered, as stipulated by the law of June 2, 1941. This led to the creation of a dossier by the “Service des Juifs” of the Seine department, numbered 100.549.

It is not known what Arthur did after Vilma was arrested on July 3, 1942.

Was he sent to Bordeaux by the Austrian Communist Party? Feeling threatened, did he flee of his own accord? Bordeaux was not exactly the best of place to take refuge.

It was there that he was arrested, after having been denounced, according to Vilma. He was then living at 1, rue Marcel, which is between two roads called the cours de l’Argonne and the cours de l’Yser, not far from the Nanssouty district.

Arthur was sent to Fresnes prison on December 2, 1943. He was then transferred to Drancy on July 25, 1944 where he was given the number 25,954. The search register drawn up on his arrival in Drancy states that Arthur was in possession of 3,300 francs[9].

He was deported to Auschwitz, on convoy n°77 on July 31, 1944.

Like Vilma, Arthur was selected to work. The serial number B3825 was tattooed on his arm.

Vilma joined the communist resistance network within the camp and managed to work in the SS laundry, which was located in the men’s camp. This meant that she could communicate with Arthur.

The advancing Soviet troops in January 1945 prompted the Nazis to evacuate the camp. The evacuations took place from January 17 to 21 [10].

Both Arthur and Vilma took part in the Death Marches [11] during which it is estimated that there were about 59,000 deportees from Auschwitz-Birkenau and the associated camps (Monowitz, Bobrek, Jaworzno and Blechhammer), the majority of whom walked for around three days and two nights..

Arthur’s itinerary was as follows: Auschwitz/Gross-Rosen, Gross-Rosen/Dachau. This was a very long trek indeed, of almost 500 miles.

The survivors’ accounts give us a glimpse of what the deportees’ distress must have been like. Such testimonies have made it possible to retrace the appalling journeys made by these groups. As we follow them, we can try to imagine what these marches were like for Arthur, Vilma and all the deportees[12].

While some were able to secure some food, most left with nothing.

These convoys were unscheduled, so the SS stopped to rest when circumstances permitted. No food was given to the prisoners. Their clothing provided little warmth, and their shoes inflicted further suffering on most of them. The clothing would have included “convicts” uniforms or randomly collected garments taken from the dead, who had been gassed as soon as they arrived at the camp. As for the shoes, if they were Holzschuhe (wooden-soled canvas “clogs”), they were uncomfortable and tended to fall off. While they looked relatively normal, they often did not match and did not protect the feet from freezing temperatures.

Many people were sick. The weakest were executed along the way.

After these marches, most of the survivors were transported in open freight cars as the snow fell and temperatures fluctuated between -20° and -30° Celsius (-4° and -22° Fahrenheit). They were all crammed in together in the wagons, the living sometimes on top of the dead.

There are no or very few stops, and no food or water was given out.

Arthur finally arrived in Gross-Rosen. This camp, opened in August 1940, was in Silesia, south of the Oder River. It was about 40 miles from Breslau, near the town of the same name, which in Polish is called Rogosnica.

The arrival of deportees from the camps further east caused overcrowding, which led to a typhus epidemic and, between February 8 and March 23, 1945, the camp had to be evacuated again, this time to KL Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Dachau and in particular Dora. More than 30,000 people were loaded onto open trains, which resulted in horrendous carnage.

Arthur does not seem to have stayed long in Gross-Rosen, however, since on January 28, 1945[13] he was transferred to the Dachau concentration camp, about 15 km northwest of Munich, in Bavaria, in southern Germany.

His prisoner registration number was 140224[14]. On the list of people transferred from Auschwitz to Dachau, Arthur was referred to as a “Kürschner”, i.e., furrier, a profession he had carried out in the past. He was assigned to Kommando Waldlager V as a “Anstreicher”, or painter [15], and then from that date on he was an “Arbeiter”, or worker, assigned to the outdoor “Kommandos” at the Dachau concentration camp. It was under the management of Kommando Mühldorf-H.P.K. of the Todt organization, that he worked until March 26, 1945. On that date, he was sent back to the Dachau camp.

Arthur died just two days later, on March 28, in Dachau [16]. The camp was liberated on April 29, 1945.

Vilma, after enduring a 125-mile forced march, was deported in an open freight car to Ravensbrück. She was then released, thanks to the Red Cross and Swedish diplomats who negotiated and organized the evacuation of a number of deportees, first by Switzerland and then by Sweden.

Ruth Steindling tried to find out the circumstances of Arthur’s death by interviewing the staff at the Dachau Memorial. She was told that the fact that Arthur was transferred to the main camp on the 26th and died two days later suggests that he was executed. Indeed, the last few days before the liberation of the camp were marked by a series of summary executions, in particular of members of a clandestine resistance network of communists and social democrats, which had been set up at the end of 1944.

There is, however, no hard evidence that Arthur was one of their victims. The last few months before the liberation of the camp account for half of the camp’s deaths between 1938 and 1945. This high mortality rate is attributable to the deplorable living conditions in the camp: poor nutrition, lack of hygiene, epidemics, overcrowding etc. Did Arthur in fact succumb to the mistreatment that he had suffered throughout months of successive deportations?

Having decided to return to France rather than Austria, Vilma heard through the Communist Party that Arthur was alive and was thought to have gone back to Vienna. She then went to the Austrian capital to try to find him, only to learn that Arthur was dead.

Similarly, a telegram was sent to Elias, Arthur’s father, telling him that his son had been released “recently” by the Red Army and that he was awaiting repatriation.

Elias only received formal notification of his son’s death in 1956.

Arthur’s death certificate is registered in Bad Arolsen, under the reference Dachau 1329/53.

References

[1] Biography of Vilma Steindling written by Ruth Steindling, her daughter. It was on meeting Ruth that part of the veil that covered Arthur’s life was lifted. Vilma Steindling: Eine Judische Kommunistin im Widerstand Mit einem Nachwort von Anton Pelinka by Ruth Steindling and Claudia Erdheim https://amalthea.at/produkt/vilma-steindling /

[2] Summary provided by Ruth Steindling

[3] Document from the Préfecture de Police Archives indexed APP_77W536: investigation sheet from the Paris Foreign and Jewish Affairs Service, dated 1943.

[4] According to Direction des étrangers et des Affaires juives (Department of Jewish affairs), report dated March 17, 1943

[5] Kristallnacht, a vast pogrom carried out in 1938 by the Nazis against the Jews in Germany and annexed Austria. November 9-10, 1938.

[6] Cairn, La fabrique des clandestins en France, 1938-1940. Riadh Ben Khalifa. Dans Migrations Société 2012/1 (N° 139), pages 11 à 26. https://www.cairn.info

[7] Opus cited: Ruth Steindling, Vilma Steindling: Eine Judische Kommunistin im Widerstand Mit

[8] Ruth Steindling: “Not a worker” identity card issued by the French administration in the name of Arthur Kreindel, dated November 20, 1941.

[9] Mémorial de la Shoah – The Shoah Memorial, in Paris.

[10] The following facts are based on: http://www.cercleshoah.org/ Death march, the evacuation of Auschwitz I, January 1945. Witness testimony of Henri Graff given on October 5, 2005 for the UDA. Published on Sunday, March 31, 2013. Martine Giboureau, professor of history-geography-civic education, April 2013.

[11] Ibid: “Death marches is the term commonly used to describe the evacuations of camps by the Nazis as the Soviet armies approached from the east and the British-American armies from the west. The first camps evacuated in January 1945 were located in occupied Poland.

It was the direct threat of the Soviet army liberating the Baltic States and Poland, engaged in Operation Vistula-Oder, between 12 January and 3 February 1945, that precipitated the evacuation of Auschwitz-Birkenau and annex camps (Monowitz, Bobrek, Jaworzno, Blechhammer) from January 17 to 21, day and night, in the cold, snow and rain.

In the spring of 1945 it was the camps in the west [2] of the Grand Reich that were vacated.

[12] Ibid. http://www.cercleshoah.org/ Death march, evacuation of Auschwitz I, January 1945. Witness statement by Henri Graff made on October 5, 2005 for the UDA. Published on Sunday, March 31, 2013.

[13] ITS – International Committee of the Red Cross, International Tracing Service. January 28, 1958.

[14] Ibid. ITS. List of prisoners in the outside works Kommando group at Dachau Concentration Camp, February 17-28, 1945.

[15] ITS Archives, Bad Arolsen, Dachau list, Kommando Waldlager V.

[16] Ibid. ITS. List of the dead from the Dachau concentration camp / Death certificate (correspondence file).

(German version and images)

Contributor(s)

Thibaud FLEURY, history and geography teacher and his class of 11th grade students at the Philadelphia de Gerde high school in Gradignan, France.

Arthur KREINDEL

Arthur wurde am 27 Juni 1916 in Wien, Österreich geboren. Sein Vater hiess Elias Kreindel, 1879 in Krakau geboren und seine Mutter Rosa, geb. Gerowicz ist 1889 in Wien geboren. Er war der älteste von insgesamt vier Geschwistern. Er machte eine Ausbildung zum Kürschner und war Mitglied beim Kommunsitischen Jugendverband KJV, wo er auch seine Lebensgefährtin Vilma kennenlernte.

Zu Vilma Steindling, geb. Geiringer , ist zu sagen, dass sie in einer sehr armen, jüdischen Familie aufwuchs. Als sie drei jahre alt war, verstarb ihr Vater, 5 Jahre später wurde ihre Mutter sehr krank, sodass Vilma sie, bis zu ihrem Tod pflegen musste. Mit nur 8 Jahren lebte sie also als jüdische Waise im 19. Bezirk von Wien. Mit 14 Jahren begann sie eine Ausbildung zur Modistin und wohnte im jüdischen Wohnheim für Auszubildene.

Sehr früh hatte sie das Bedürfnis sich sozial zu engagieren. Deshalb trat sie mit 15 Jahren dem KJV bei.

1933 wurde die KPÖ verboten und die Unterdrückung zwang Arthur Wien zu verlassen und nach Paris zu ziehen, wo er seinem Beruf in einem Atelier in der 24, rue d’Enghien im 10. Arrondissement nachging. Er wohnte in der 31, rue Bergère.

Nachdem Vilma ihre Ausbildung abgeschlossen hatte, zog sie im Herbst 1937 zu Arthur, wenige Monate vor dem Anschluss Österreichs an das Deutsche Reich.

Die Ausschreitungen gegen Juden in Österreich wurden unhaltbar. Daher versuchte Kreindel Visa für seine Eltern, Brüder und seine Schwester zu beantragen. Am Vortag der Reichspogromnacht verlies seine Familie Wien Richtung Paris.

Mit dem Einmarsch der Nazis in Polen am 1. September 1939 begann der Zweite Weltkrieg. In Frankreich, ein durch Immigration geprägtes Land, änderten sich damit die Einwanderungsgesetze. Am 10. April 1938, wurde Édouard Daladier der Premierminister. Sein Innenminister Albert Sarraut setzte eine Politik um, die die Gesetzeslage gegenüber der ausländischen Polizei verschärfte. Der Ausbruch des Krieges führte zur Verhaftung einiger Beamten, die unter Verdacht standen, Mitglieder der Fünften Kolonne zu sein oder als Kommunisten, Sozialisten oder Anti-Nazis, also Feinde angesehen wurden. Mit dieser Massnahme, konnten die Behörden den Verwahrungsvollzug rechtfertigen.

Möglicherweise war Arthur, wie andere östrerreichische Flüchtlinge im Stadion von Colombes interniert.

Vilma verlies Paris Richtung Tarn und Garonne bei Grisolles mit einer Gruppe von Mädchen und Jungen. Dort verbrachte sie den Frühling, Sommer und Herbst 1940. Danach kam sie nach Paris zurück, wo Arthur befreit wurde. Ab 1942 wohnten die beiden im Banlieu von Paris und waren im Widerstand aktiv. Vilma engagierte sich gemeinsam mit anderen Frauen aus Österreich bei der Mädelarbeit : die jungen Frauen sollten Soldaten von der Absurdität des Krieges überzeugen und ihnen raten, ihre Tätigkeit als Soldaten aufzugeben, da der Krieg nicht mehr zu gewinnen sei. Diese Arbeit war sehr gefährlich, da die Frauen riskierten,verhaftet zu werden.

Vilma war die erste, der genau das passierte.

Nach einem zweitem Treffen mit einem deutschen Soldaten, wurde sie von zwei deutschen Polizisten verhaftet und nach Fresnes gebracht. Nach drei Monaten musstr sie sich dem Gericht stellen und wurde zu fünf Jahren Gefängnishaft verurteilt. Sie verbrachte drei Monat im Fort de Romainville und wurde dann zuerst zur Petite Roquette und schliesslich im August 1943 nach Drancy übermittelt. Am 2. Oktober 1943 wird sie mit dem Convoi Nr.59 nach Auschwitz deportiert und zum Arbeiten eingeteilt. Ihr Arm wird mit der Nummer 58337 tätowiert.

Am 20. November 1941 erhält Arthur einen Pass (Kartennummer 59AS63938) « für Ausländer ». In dem 19 Seiten langen Heft, steht ausserdem « nicht erwerbstätig ». Die folgenden Seiten zeigen ein Foto von ihm und nennen seinen Familienstand. In grossen, roten Buchstaben ist zu lesen « jude ». Die genannte Adresse lautet 31, rue Bergère, Paris.

Hier enden die Spuren und Quellen. Am 17. März 1943 wird von den Renseignements généraux und der Direction des étrangers et des affaires juives de Paris ein Dokument herausgegeben, indem zu lesen ist, dass Arthur « seit Januar oder Februar 1940 in der zone libre lebt». Aus dem Dokument geht auch hervor, dass seit Juni 1940 keine Aktivität mehr zu sehen ist, ausser einem Eintrag im Handelsregister (Registre du commerce) unter der Nummer 688069.

Durch ein Dokument, welches durch emmigierte Familienangehörige bereitgestellt wurde, erfährt man, dass sein Vater Elias im Dezember 1944 der Zeitung « l’Auto » geschrieben hat und so versuchte, seinen Sohn zu finden. Ein Mitarbeiter informierte ihn darüber, dass Arthur die Räumlichkeiten verlassen habe und am 27.Juni 1943 gekündigt habe.

An dieser Stelle ist es notwendig, die Gesetze von Vichy in Bezug auf den Status der Juden und die Volkszählung zu erläutern, die durch General Petain unterzeichnet wurden.

Der sogenannte « premier statut des juifs » von Vichy (Oktober 1940) schloss Juden von jeglichen öffentlichen Ämtern, in Verwaltung und Staat sowie dem Militär der Justitz und Bildung aus. Neben dem Verbot der Leitung einer Pressefirma, eines Kinos, Theaters oder Radios, gab es ausserdem das Prinzip der Quotenregelung zur Begrenzung der Zahlen der Juden in den jeweiligen Berufen. Der « deuxième statut » listet die verbotenen Berufe auf und sieht eine prinzipielle Einschränkung der freien Berufswahl im Handel, Industrie und Handwerk vor.

Im Juni 1941 wird zum ersten Mal das « Recht zur Internierung in ein Speziallager auch wenn es sich um ein französicheches Interesse handelt. »umgesetzt.

Diese Gesteze haben zur Konsequenz, dass Arthur nicht mehr arbeiten darf. Laut den Akten der Ausländerbehörde im Bezug auf jüdische Bürger von Paris, musste Arthur sich zur Registreirung vorstellen, wie es das Gesetz vom 2.Juni 1941 vorsieht.

Es ist nicht bekannt, was Arthur nach der Verhaftung von Vilma am 3.Juli 1942 gemacht hat. Wurde er von der KPÖ nach Bordeaux geschickt? Fühlte er sich bedroht und floh alleine ? Bordeaux war nicht unbedingt der Beste Ort um Zuflucht zu finden.

Er wird dort verhaftet, nachdem er, wie Vilma erzählt, verrraten wurde. Er wohnte in der 1, rue Marcel, in der Nähe des Nanssouty Viertels.

Er wurde am 2. Dezember 1943 nach Fresnes ins Gefängnis geschickt. Am 25.Juli 1944 wurde er dann unter der Kennnummer 25 954 nach Drancy übermittelt. In dem bei seiner Ankunft erstellten Heft steht, dass er zu diesem Zeitpunkt 3300 Francs besass.

Am 31.Juli 1944 wurde er schliesslich mit dem Wagen Nr .77 nach Auschwitz deportiert. Wie auch Vilma, ist Artuhr zum Arbeiten ausgewähltworden. Ihm wird die Nummer B3825 auf den Arm tätowiert. Vilma musste in der Wäscherei arbeiten, die sich im Lager der Männer befand. So hatte sie die Möglichkeit, mit Artuhr zu kommunizieren.

Als sich die Rote Armee im Januar 1945 annäherten, evaquierten die Nazis das Lager zwischen dem 17. und 21. Januar.

Wie viele andere Deportierte von Auschwitz-Birkenau, gingen auch Vilam und Artur die Todesmärsche. Die meisten von ihnen liefen ungefähr drei Tage und zwei Nächte.

Die Erzählungen von Zeitzeugen lassen das Leiden der Opfer erahnen. Man kann sich also vorstellen, was die Märsche für Vilma und Artuhr und die vielen anderen Deportierten bedeutet haben. Während einige etwas zu essen bekamen, hatte die Mehrheit gar nichts. Die Kleidung hielt nur sehr wenig warm und die Schuhe verursachten grosse Schmerzen. Die Anziehsachen waren Häftlingskleidung oder die Kleidung der Deportierten, die direkt nach ihrer Ankunft den Tod ihn den Gaskammer starben. Viele waren sehr krank und die schwächsten wurden auf dem Weg umgebracht. Nach diesen langen Fussmärschen,ging es in Güterwägen weiter, während es draussen schneite und die Temperaturen bis -20° und -30° fielen. In den Wagen lagen sie übereinander, manchmal sogar die lebenden auf den Leichen.

Nch dem Todesmarsch kam Arthur von zunächst nach Gross-Rosen. Das Lager wurde im August 1940 geöffnet und befindet sich in Schlesien im Süden der Oder und 60 km von Breslau.

Die Ankunft der Häftlinge aus den östlichen Lagern, sorgte für eine Überpopulation, die eine Typhusepedimie auslöste. Zwischen dem 8. Februar und 23. März 1945, mussten die Häftlinge nach Buchenwald, Flossenbürg, Dachau und vorallem Dora verlegt werden Mehr als 30 000 Häftlinge waren unter schlimmsten Bedingungen in Zügen eingepfercht.

Aber Arthur blieb nicht lange in Gross-Rosen. Am 28 Januar 1945 wird er in das Konzentrationslager Dachau deportiert, ungefähr 15 km nord-westlich von München. Seine Gefangenennummer war 140224.

In der Deportationsliste von Auschwitz wird Arthur als « Kürschner » erkannt. Er wird als Maler zum Gebäude « Anstreicher » beim Kommando Waldlager V eingesetzt, danach wird er zu einem angeblichen « Arbeiter » der inneren «Kommandos » des Lagers Dachau. Beim Kommando Mühldorf-H.P.K., welches abhängig war von der Organisation Todt, arbeitete Artuhr bis zum 26 März 1945. An diesem Tag wird er nach Dachau zurückgeschickt. Dort stirbt er 2 Tag später am 28. März. Am 29. April 45 wird das lager befreit.

Nach dem 200 km langen Fussmarsch, wurde Wilma in einem Viehwagen nach Ravensbrück deportiert. Dank Verhandlungen mit den Roten Kreuz und der schwedischen Dipolomatie wurde sie befreit, nachdem die Evakuierung einiger Deportierten organisiert wurde, durch die Schweiz und dann durch Schweden.

Ruth Steindling versuchte die Umstände von Artuhrs Tod bei der Gedenksätte Dachau zu erfragen. Sie fand heraus, dass er vermutlich exekutiert wurde, da er nur 2 Tage nach seiner Ankunft im Hauptlager starb. In der Tat gab es kurz vor der Befreiung des Lagers eine Reihe von Exekutionen, die besonders auf eine 1944 von Sozialdemokatraten und Kommunisten gegründete Widerstandsbewegung abzielte.

Die Todesfälle in den letzten Monaten vor der Befreiung des Lagers machen die Hälfte aller zwischen 1938 und 1945 aus. Diese hohe Sterblichkeit ist auf Lebensbedingungen in Lager zurückzuführen ( Ernährung, Hygiene, Krankheiten,…)Ist Artuhr durch die schlechten Bedingungen und Behandlungen während den Monaten als Deportierter gestorben?

Entschieden nach Frankreich zurückzukehren, erfuhr Vilma durch die Kommunistische Partei, dass Artur lebe und das er nach Wien gegangen sei. Als sie in Wien eintraf,erfuhr sie, dass er gestorben ist.

Elias, dem Vater von Artuhr, wurde ein Telegramm geschickt um ihm mitzuteilen, dass sein Sohn von der Roten Armee befreit wurde und auf seine Rückführung warte. Erst 1956 bekommt er die offizielle Bestätigung des Todes seines Sohnes. Die Sterbeurkunde ist in Bad Arolsen unter der Nummer Dachau 1329/53 zu finden.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Hello! Elias Kreindel is my great great grandfather, as I am descended from his daughter, Gertrude Kreindel, sister of Arthur who is mentioned in this article. She is the mother of my paternal grandmother.

I wanted to say, thanks for posting the story! it is very interesting for me to read about my ancestors! As far as I know, however, my great great grandma, Arthurs Mother, was called Rosa Gewürz. Is this wrong?