Perlette DRAÏ, 1925 – 2018

This fictional autobiography was written by 9th grade students at Les Blés d’or junior high school in Bailly-Romainvilliers, in the Seine-et-Marne department of France. Our information was taken from archival documents provided by the Convoy 77 association and from the websites of the Paris archives, the Shoah Memorial in Paris and Yad Vashem, as well as from some books we read during the year:

Le journal d’Hélène Berr (Hélène Berr’s diary), Merci d’avoir survécu (Thanks for having survived) by Henri Borlant, Retour à Birkenau (Return to Birkenau) by Ginette Kolinka and J’ai pas pleuré (I did not cry) by Ida Grinspan.

Other students in the class researched the other members of the Draï family who were deported (see the biographies of Berthe, Marcel and Charles).

I am going to tell you about my life, in detail and without pretense. I promise you, dear readers, that I will tell you only the truth. I do not wish to lie to make the story more interesting or to please you. This autobiography is going to tell the story of my life as a Jew during the Second World War.

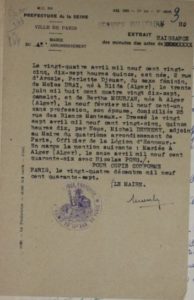

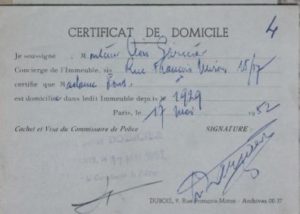

My name is Perlette Draï and I was born on April 24, 1925 at 5:25 p.m. in a hospital at 2, rue Arcole in the 4th district of Paris. From 1929 on, I lived with my parents and four brothers in an apartment building at 15 rue François Miron, also in the 4th district.

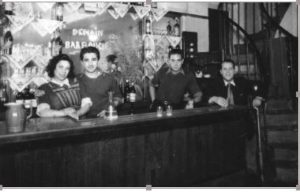

My parents were both from Algeria, which was a department of France at the time. My mother, Berthe Mourjan, was born in 1901 in Algiers and my father, Moïse Draï, was born in 1897 in Blida. My mother was a homemaker and my father owned a bar called “Maurice”, which was on the ground floor of our building. I was the elder sister of four brothers, Marcel born in 1926; Charles, 1930; Roger, 1933 and Richard, 1939.

The neighborhood, in which we had lived for several years, was home to a large Jewish community. There were many well-known cafés on rue François Miron, which were very important to the Blackfoot Jewish community. The “Jaïs”, which was on the corner of the street, as well as the “Lalo”, were both large cafés mainly frequented by people from Algeria or Tunisia. The neighborhood was called the “pletzl” which means “little place” in Yiddish. We had always made a habit of observing Algerian culinary traditions, such as eating barbouche on Fridays. I loved my neighborhood, the atmosphere and the family spirit that surrounded us.

Café Lalo Picture removed by the editor

Café Jaïs

barbouche

Photo of café Maurice removed by the editor, because it is submitted to reproduction rights by Paris La Douce

As you can see, the barbouche came will all the trimmings. I loved it when I had to serve this dish to my father’s clients and I would sneak into the kitchen to get a sniff of that mouth-watering smell. It was as if we were one big family and we met up every day in the “Maurice” bar to spend more time together.

Unfortunately, from the spring of 1940 onwards, nothing was the same as before. France had just lost the battle and the Germans had invaded the streets of Paris. In addition to the war-related shortages and restrictions, we were gradually subjected to even further restrictions due to the fact that we were Jewish. People began to lose their jobs, propaganda posters in the streets portrayed us as thieves and murderers and the atmosphere became increasingly hostile. From 1941 onwards, neighbors began to disappear and were never heard from again, and my parents spoke of roundups. As if hatred and despair were descending on us, my father lost his job in 1942 as a result of a new restriction that removed the rights of Jewish business people. The bar had to be handed over to a non-Jew. My father’s sadness made me nervous. He was not the same as before; there was no joy on his face. All you could see were his expressions shutting down. He always seemed to be upset and sometimes he couldn’t sleep. We were subjected to so many restrictions. The little ones were not allowed in the park anymore, like dogs. That’s what we were reduced to. In the subway, we had to ride in the last car. We are no longer allowed to own a bicycle, a radio, buy flowers or anything else to treat ourselves. Shopping became impossible because even there we could only go to the stores at times reserved for Jews. We disappeared entirely from ordinary life.

A decree was passed on October 3, 1940. It stated that “any person descended from three grandparents of the Jewish race or from two grandparents of the same race if his or her spouse was Jewish” was considered a Jew. After this, many other decrees followed, including one that obliged Jews register themselves as such and to have a “J”, meaning “Jew” stamped on their identity card.

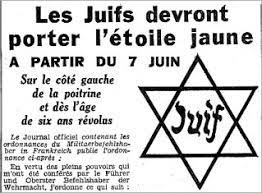

As of June 7, 1942, we had to wear the Star of David sewn on our clothes. Can you imagine the embarrassment we when people looked at us with their judgmental expressions?

In 1942, all around me I saw people being arrested, including my father’s friends and clients. In September, my parents decided to send my brothers to the free zone. Roger and Richard arrived safely, but we found out that Marcel and Charles were arrested when they crossed the demarcation line illegally on September 30, at La Rochefoucauld, in the Charente department. They spent three weeks prison in Angoulême. When they left, we hoped that they would be able to live a better life in the free zone than if they had stayed in Paris, so when they came back again, we were very disappointed. They told us how they had been interrogated to make them confess their religion and how Marcel had held out and not confessed to anything, despite the beatings he had suffered. We realized that the vice was closing in on us and how lucky they had both been. Apart from all this, we were still very worried and I tried to keep hope alive to support my parents. Well, until the day in 1943 when my father was arrested and taken to the camp in Pithiviers, and after that we had no further news of him. The atmosphere at home was very tense, and we worried even more because my father had been the cornerstone of the family.

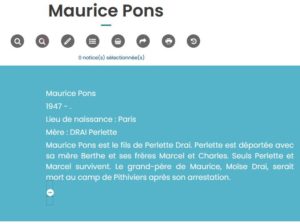

We have not been able to find any information on Moses Draï or his arrest, nor is he listed on the Shoah Memorial or the Yad Vashem websites. His grandson Maurice, Perlette’s son, did however testify to the Shoah Memorial in Paris that he was arrested and died in the Pithiviers camp. The camp was in operation from 1941 to 1943, so we suppose that he was interned and died there in 1943. He is not on the lists of deportees on any of the convoys. As for Richard and Robert, we also suppose that they must have remained hidden in the countryside, because they were not on the deported persons lists either. The next trace of them is in 1952, on the application for Berthe to be granted “Political Deportee” status, when their uncle Prosper granted Perlette power of attorney to apply for the deportation records of her missing mother and brother. At the time, he was the brothers’ legal guardian, perhaps because he took care of them in the free zone during the war.

On July 7, 1944, at a time when the neighborhood was calm and peaceful, we heard a knock on the door. It was three o’clock in the morning. The police marched into our house and ordered us to follow them. We gathered our bags and our most precious belongings. I never knew if all the other arrests were identical, but I thought that perhaps ours was calmer than most because we were expecting it. A lot of local Jewish people had already been arrested, including Armand Guedj. Bluma Felentzier was arrested at the same time as us. With us in our misery, there was no need for the use of force during our arrest. However, we soon understood, when we arrived at a camp called Drancy, that this was just the beginning of the hell.

In Drancy, I met two young girls of my own age with whom I became friendly; Germaine Akierman and Mathilde Jaffé. Their friendship softened the pain of imprisonment. I stayed in the camp for about twenty days, which were the longest and most memorable days of my life.

When I arrived, after having had my identity papers taken away, I was put in a women’s dormitory. We lay on boards or on the floor, without even straw mattresses or blankets. There were 60 of us in each room and the living conditions were very difficult due to the lack of food and healthcare. Each day, we were only given one piece of bread and three portions of thin soup with no vegetables in it, which we had to share.

Drancy camp, with Jewish deportees in the background and a French gendarme in the foreground, watching over the prisoners

Women doing their chores in Drancy camp

Aerial view of Drancy

On July 31, we were put on buses and taken to Bobigny railroad station. There, we were made to get into cattle cars, all crammed in together. It was a narrow, confined space and there were about a hundred of us in there.

I spent three days in abominable conditions but I did not die, that was the main thing. Luckily, I was with my friends Germaine and Mathilde. We tried to keep ourselves occupied together but it was very difficult because everyone on the convoy was a bit panicky, not knowing where we were going, if we were going to be separated from our families or what was going to happen to us. We all had one thing in common; we were wearing the yellow star. As for food and water, there was nothing but the meager supplies we had brought with us.

To relieve ourselves, there was just one bucket in the corner of the car, so we had no privacy and the smell was foul since the container filled up very quickly and we could not empty it. The stench soon became unbearable.

Here is the route taken by the majority of deportees from France during the Second World War, from Drancy to Auschwitz-Birkenau (Source: Yad Vashem)

I was tired, or more accurately, exhausted. I thought I was dreaming when the car stopped. I felt nervous about what might happen next, but I tried to reassure myself so as not to go crazy. My body felt numb but I had to get out of the cattle car quickly because the SS were shouting at us. The lights were blinding, and I lost sight of Germaine and Mathilde, who must have already been pushed out of the wagon.

When we got off, I was stunned by the incessant screaming and barking and an acrid smell that stung my nose. Then we were separated into two lines, one mainly for men and one for women and children. We were asked to leave our things on the platform and told to stand in these lines. It was then that I found Germaine and Mathilde. I saw my mother and Charles in the other line, but I didn’t know where Marcel was. As soon as our eyes met, I was called away. I couldn’t even say goodbye to them, or give them one last hug… I was mentally as well as physically exhausted, all I could do was walk, with a blank stare, a blank face and a sinking heart…

Germaine’s testimony reveals that Mengele himself took part in the selection process on that day, looking for children and a certain type of women to perform his experiments on. These photos, from the Auschwitz album, were taken by the Nazis in May 1944 when the Hungarian convoys arrived. They are the only photographic evidence of the selection. They were taken on the platform at Birkenau and the camp gate can be seen in the distance.

We entered the camp and were sent to a wooden hut, where the SS ordered us to undress. There was no privacy, so we had to take off our clothes in front of them. Then they took us to the communal showers where we were disinfected.

After washing, they shaved our entire bodies, not leaving even a single hair. I no longer looked like a young woman and I was terribly humiliated, standing naked in front of everyone. They then tattooed a number on our arms, no doubt for identification purposes. Now we were nothing but numbers, which we had to learn by heart in German. We were then given clothes to put on, which were either worn out or too big.

When we were all done, they assembled us in small groups and gave us some leftover food: a small piece of stale bread and soup consisting mainly of water.

We were then moved to our barracks, where we were to share beds and latrines; our living conditions were going to be very difficult. I hardly closed my eyes at night, I was so anxious. I was worried about my mother and my little brother and when we asked about the other group, people pointed out the chimneys and the sky. I was too afraid to figure it out; I didn’t want to know.

The next day, we were woken up very early and there was a very long roll call during which we all had to give our numbers in German. They lined us up and counted us several times. I was number 16693.

We are then sent to work, where we had to move stones around for no reason. The men were digging ditches, and some groups of women were pulling carts. It was very hard work. When people balked or gave up due to lack of strength, the SS beat them with truncheons. I always looked away when this happened; I couldn’t stand all this violence.

For months and months, we continued to work hard. I could hardly stand up, and my feet hurt like hell. In October 1944, we were sent to Kratzau, a different camp, again in cattle cars, but these were even more crowded than the ones in which we were transferred from Drancy. A lot of people died during the journey.

In Kratzau, we worked in weapons factories, which was an advantage for us because at least we were sheltered from the weather. Our only wish was that the factory would be bombed. Some of us would rather die in the bombing than continue this inhuman, degrading life.

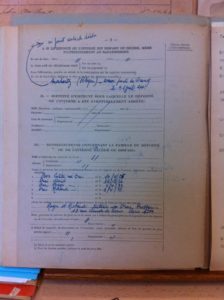

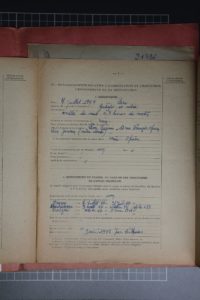

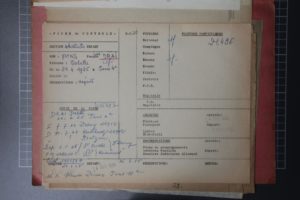

This document outlines the various stages of Perlette’s journey, from her arrest to liberation, and also the number that she was assigned in Birkenau

This French medical card tells us about Perlette’s transfer from Auschwitz to Kratzau, which was a sub-camp of Gross-Rosen, itself a satellite camp of Sachsen-Hausen, located in the Sudetenland. On the back, there is a note about Perlette’s weight loss. The camp was liberated on May 9, 1945 by the Red Army, as testified by Régine Jacubert, who was also deported on Convoy 77 and followed the same itinerary as Perlette.

Perlette and Régine were repatriated at the same time, on June 3, 1945, to Saint Avold in France. It was suggested that they go to Paris and the Lutétia Hotel but Régine chose to go to Nancy, unlike Perlette, who came from Paris

I still asked myself how I could have survived all that. We were taken to Paris, more specifically to the Lutétia Hotel, to locate other members of our family: this was where the repatriation services were based, and everyone came to find or ask for news of their missing relatives. The walls were covered with photos and search notices. This is how I met up with my little brother, Marcel. We soon came to terms with the fact that the rest of our family had disappeared, and so began the long administrative process to have them recognized as victims of war.

In the end, I decided to move to Algiers, where I lived at 16 rue Naudet. Life in Paris had become too painful for me; I was consumed by the guilt of being alive. There I met Raphael Pons, my future husband, whom I married on April 11, 1946 in Algiers. Soon afterwards, we returned to Paris to continue the family tradition by taking over the bar again. In 1947, we had a son, Maurice Pons, who was named in memory of my father, Moïse.

This photo, taken in 1946, shows Perlette and her husband, Marcel and Armand Guedj, who was arrested at the same time as the Draï family. Perlette was pregnant at the time.

I gave two testimonials, one about my brother and the other about my mother, in which I explained what happened. I applied for the title of political deportee for my mother, my brother and myself, which was granted on July 9, 1955 by the Ministry of Veterans and Victims of War. Two other witnesses, Garnier Léon and Jeannin Léon, also testified that I was arrested on July 7, 1944.

I also went to collect my little brothers, Roger and Richard, who had been taken in by my uncle. They were still so young; Roger was 12 and Richard was 7. As soon as I saw them, I threw my arms around them. They had grown so much since the last time I had seen them, when they left for the free zone, and I couldn’t stop crying. I took them in and became their guardian so that they could grow up with their family. Raphael accepted them right away and we began to rebuild our family.

The French Republic paid me the deportees’ allowance. The State compensated us to the tune of 13,200 Francs in 1956. Like most other deportees, I suffered from many psychological after-effects. I had lost all my self-worth as a result of being put down by the Nazis. I had lost a lot of weight due to lack of food. It was long time before I could get back on my feet.

In the 2000s, I made the decision to leave Paris, leaving my brothers Marcel, Roger and Richard behind.

I moved to Antibes with Raphaël and Maurice. We lived at 3, avenue des Dames Blanches, in a relatively quiet neighborhood. I remember I had a phone call with journalist from Jewpop on July 15, 2005, when he was interviewing people who were originally from North Africa and who had lived in the Marais district before and after the Second World War.

Here is a photo of my street in Antibes; it was a big change from Paris

It was in this Jewpop article that we found the photo of Perlette in her father’s bar in 1946, and learned about the atmosphere in the Pletzl neighborhood before the war

What became of Bar Maurice? All I know is that it became an informal- type restaurant, and that it is now called the Pamela Popo

On April 16, 2018, I left behind my son Maurice to join Raphael, my husband, who died on October 1, 2012.

Léann, Séréna, Iris, Loréna, Eva, Elyna and Lou-Ann.

Français

Français Polski

Polski

Un grand merci aux élèves de Romainville

Je suis Alain Jablonski fils de Germaine , la compagne de Perlette .Vous avez décrit parfaitement , dans les moindres détails, ce qu’elles subirent .