Régina Bernstein

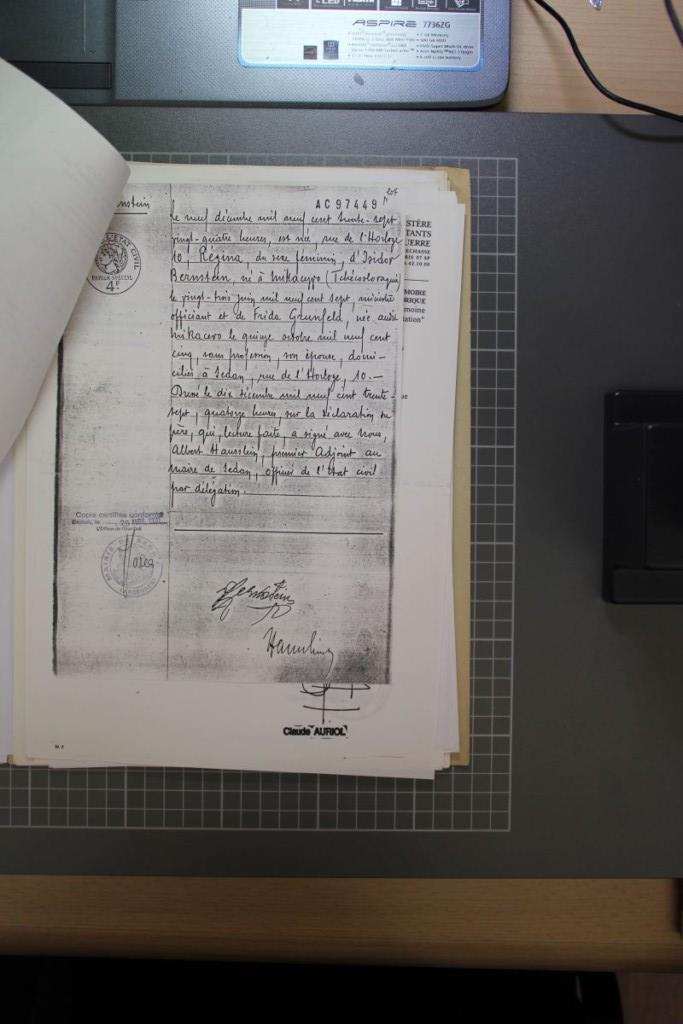

Since there are no photographs of Regina, we are showing her birth certificate.

Preamble or note of intent, written by the author, addressed to the association:

Bourges, June 21, 2020.Madam, Sir, members of the Convoy 77 association,

I am writing to send you my most sincere greetings. My name is Justine Martin-Billon. I am a 10th grade student at the Marguerite-de-Navarre high school in Bourges.

I was made aware of your remembrance project by my teacher, Mr. Stanley Théry, and by my history and geography teacher, Ms. Pavlina Dublé.

There are no words to describe the immense joy and honor that I felt in taking part in this project. Beyond writing a biography, the project was for me a source of enrichment, reflection and fulfillment. I was horrified to see so many atrocities, but fulfilled to be able to shed light on the life of Regina Bernstein. I have always been intrigued by this period of history. I was born and have always lived in Bourges. During the Second World War, Bourges was close to the demarcation line. There was therefore a lot of local cooperation to help get people into the free zone. In addition, my great-grandfather, Lucien Raffard, was a resistance fighter in the Orleans forest. My deepest regret is that I never knew him. However, my mother told me a lot of stories that he had passed on to her. I never walk along the Cher River, where people used to cross illegally, or in the Orleans forest without thinking about all those people and that era. This project was an opportunity for me to learn more about this period from the point of view of the Jews, whom I felt I knew too little about. I am very proud to have had the opportunity to pay tribute to this little girl and I also feel even more concerned about the importance of remembrance. We started the current project in the classroom but the lockdown put a stop to our work. I therefore used the time made available by the lockdown to Regina’s advantage. For me, it was inconceivable to leave this project unfinished. Far from wasting my time, the research enabled me to live a few moments in another world, out of time. I had the impression, as the information came in, that I was moving forward in time, that I was living with Regina and her family. I will not hide the fact that I would have preferred it to have been at a different time and that these events had never taken place.

Regrettably, however, it did take place and I will never be able to change that. On the other hand, I can do something about it having been forgotten. This is what motivated me to commit myself to your cause. I hope that the millions of lives that were lost will come out of oblivion.

I want to bring it all to light. Every story deserves to be told. Every human being is exceptional, as is his or her life. Each and every person has a place on earth and in humanity. No one person is superior to any other. Diverse origins, cultures and religions are for me a source of richness. It is all these differences that make up the essence of humankind. It is unbearable for me to think that women and men were treated like animals, or even worse. I wanted to give Regina back her true place within our nation, our world and our humanity.

I feel as though I came to know this child as I found out about the different stages of her life. I hope more than anything that my words will be of use to others visiting your site. I harbor the illusion that this biography will teach readers about the incredible strength that this little girl had in living through a horrendous war, leaving her with no choice but to survive. I have often wondered how she could have built a life for herself in such a tragic universe. I am proud to be able to pay tribute to her.

At the end of my biography you will find a poem that I wrote myself. This poem symbolizes for me an unforgettable opportunity to put my values, my convictions and my skills at the service of a cause that is close to my heart. These are words made up of more than just letters. With these words I hope to express my emotions. I would like these letters to form links and each link to symbolize one of my many different emotions. I felt enormous anger when I saw all the horrors that men were capable of; joy when I saw that this child was able to find some peace in this tragedy; sadness when I saw her so young separated from her parents; dread when I saw her grow up in a murderous atmosphere and so many other emotions as well… This poem represents for me an opportunity to be able to express the sorrow I feel when I see, read and listen to all the persecuted Jews’ testimonials. I have never known why, but from a very young age, I sensed that there was something that connected me with that time. Beyond my sorrow, I feel anger. This anger against these Nazis, defenders of a distorted and horrible ideology, makes me want to shed light on all the lives that have been forgotten, those of millions of Jews. I regret not having been able to find the family of the Righteous who took in Regina. I feel great sorrow not to be able to pay tribute to these people whose kindness was so immense. To my knowledge, these people do not appear in any registers, articles, or books.

Even though I tried every avenue available to me, none led to any success. I therefore submitted requests, delayed by the coronavirus epidemic, to the Shoah Memorial in Paris and the Yad Vashem Memorial Center. The Paris Memorial suggested people who could help me. At the time of writing this biography, these Righteous people have not yet been identified. However, I will continue my research no matter how much time and effort it takes. I wish more than anything to solve this mystery. I would like, if one day I get answers, to contact you again and to complete my biography. The story of the Jews was a succession of long journeys, difficulties and coincidences. This is also the story of my research. Although my work was hard, it was also a joy to learn new things about such an important and tragic period. I began my work by studying the documents you provided. I thought at first that I would limit myself to these documents, but curiosity pushed me to look further. I therefore began to search for the Bernstein family on other sites and found some interesting books. It was there that the thread of my research began. Each time I found any information about an event, an organization or a person that could be related to Regina’s life, I searched further. As I read, I found more and more information. I was able to retrace Régina’s life from October 9, 1942, the date of the roundup of her entire family, until July 22, 1944, and the roundup of the orphanage in La Varennes Saint Hilaire. I was thus able to begin new lines of research relating to immigration, the evacuation from the North of France to the South, life in occupied France, the day-to-day life of the Jews, roundups, internment centers, deportation, organizations that took care of children, the status and lives of children in hiding and in foster care, the Varennes orphanage and the UGIF homes, and the camps at Drancy and Auschwitz. I found it very difficult to accept that I had no answers concerning the Righteous. I finally managed to accept the idea by realizing that memories and history cannot be reconstructed in a day. The hope of one day finding the answers was also helpful. I would like to thank my teachers for giving me this chance. I would also like to thank you for offering this opportunity, even though there are no words to describe the joy I feel. I am grateful to you and I deeply hope that you will be pleased with my work. I hope that it meets your expectations and testifies to my appreciation.

My most devoted greetings

Justine Martin–Billon

Biography

First steps in life

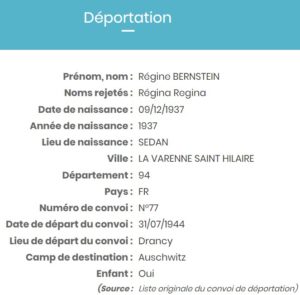

Régina Bernstein was born in Sedan, at 10 rue de l’Horloge, at midnight on December 9[1]. Her parents, the Bernsteins, had recently immigrated to France. Isidor Bernstein, born June 23, 1907, was then 30 years old and Fri(e)da Grunfeld, born October 15, 1905, was 32. Both were born in Munkacs in Czechoslovakia and both had Czechoslovak citizenship.

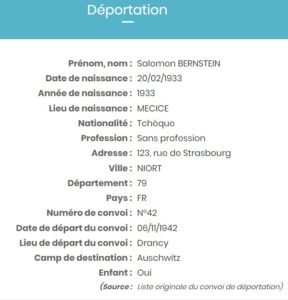

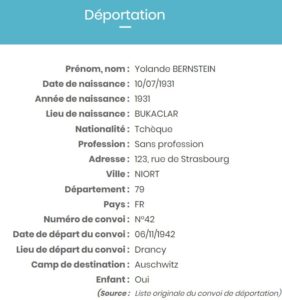

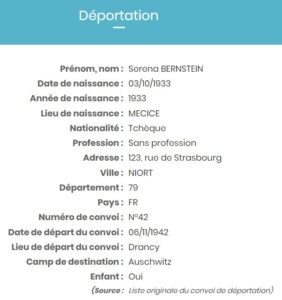

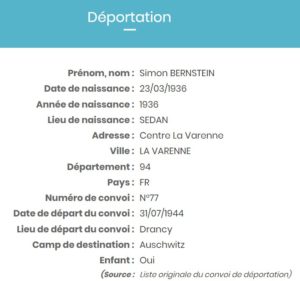

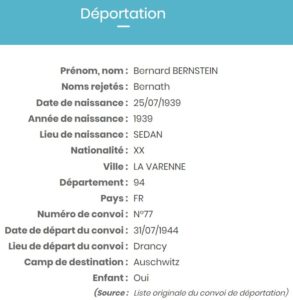

La famille était déjà riche de quatre jeunes âmes, les frères et sœurs de Régina. Les trois plus grands enfants se trouvaient être également Tchécoslovaques. The three oldest children were also Czechoslovakian. Yolande Munkacs was born on July 10, 1931 and Salomon was born on February 20, 1933 in Mecice, Czechoslovakia, as was his younger sister Serena, born on October 3, 1933 or 1934 depending on the source. The three younger children, by contrast, were French citizens, as all three were born in Sedan. First there was Simon, born on March 23, 1936, then Regina and finally, the last of the siblings, Bernath, born on July 25, 1939[2].

Between the births of Serena and Simon, the household had moved to France. Isidor Bernstein was a minister (i.e., rabbi, priest, and Jewish cleric). Mrs Bernstein did not work outside the home. When Regina was born, the family was living at 10, rue de l’Horloge in Sedan, but in later years moved to 1, rue de la Tour d’Auvergne, as it was at this address that Bernath was born[3].

The family did not arrive in Sedan in the 1930s by chance. There were already about twenty Jewish families from Poland living there[4]. They probably chose this place because there was great demand for workers in the mining and agricultural sectors. At that time, the north of France was the most industrialized and richest area of the country. In addition, the proximity to the Belgian border made it easier and quicker for people from the East to settle there.

The 1930s marked the beginning of great suffering in the countries of Eastern Europe, especially Czechoslovakia, which was facing an intense economic and political crisis. Initially, the misery was exacerbated by the Wall Street stock market crash, which occurred in 1929, but spread around Europe and the world in 1930. The Eastern European countries, which were already economically less well-developed, found themselves in great difficulty.

Fortunately, despite the restrictions on accepting foreign workers, France, which was also affected by the crisis, launched a recruitment campaign in 1934 in Poland and Czechoslovakia. Czechoslovak immigrants were helped in their daily life by the Czechoslovak Colony[5]. In addition to the already very difficult economic context, the country was facing political changes in the surrounding region, which posed a serious threat. Thus, in 1920, in the wake of the First World War, the Little Entente alliance was established. This was a diplomatic and military alliance between Czechoslovakia, Romania and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Its objective was to fight against the return of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The main consequence of this alliance was the opposition against Germany and Poland with which Czechoslovakia had to contend. In 1934, its two enemy countries signed the non-aggression treaty. This new alliance and Hitler’s accession to power on January 30, 1933, fostered increased anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe. This background of social hardship must surely have been what triggered the Bernstein family’s emigration.

The evacuation order

While the end of the 1930s was a time of growing tension, foreigners were increasingly marginalized in France. There was a rise in xenophobia in particular because of the industrial, mining and agricultural jobs occupied by foreigners in the context of the recession.

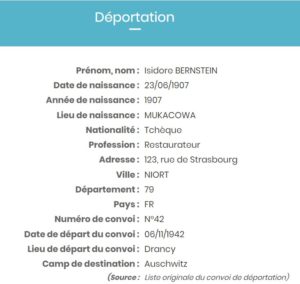

The situation then deteriorated more and more until war broke out. By May 1940, the inhabitants of Sedan and the border area had to evacuate the region. This area was the first to suffer the consequences of the German invasion, so the population had to be safeguarded[6]. All residents had to go to the prefecture, where they were assigned a place to which they should evacuate. Inhabitants of the Ardennes department, including Sedan, were assigned to the Deux-Sèvres department, including Niort[7]. Régina and her family thus moved to 123, rue de Strasbourg in Niort. Isidor Bernstein became a restaurant worker, this being listed as his profession in the register held at the Shoah Memorial in Paris[8]. Perhaps for this family man, this new occupation was a means of protecting him. Many people had to change careers, but for the Jews the opportunities were limited. The Statute of the Jews, issued by the French State of Marshal Pétain on October 3, 1940, forbade Jews from many professions including the civil service, the media, or those in which they would have contact with the public. There were no restrictions on restaurant work, and decisions were left to the goodwill of the employer[9]. Frida Bernstein, for her part, still did not go out to work.

The roundup of October 9, 1942

The beginning of the 1940s marked a decisive turning point in the social exclusion of Jews. Already excluded from many professions by the enactment of the Second Jewish Statute on June 2, 1941, they were obliged to join the UGIF, the Union Générale des Israélites de France, meaning Union of French Jews, an organization created according to the French law of November 29, 1941, which sought to represent Jews in dealings with public authorities, particularly in matters of assistance, welfare and social rehabilitation[10]. The restrictions were not only limited to professional but also to social life. Thus, according to the third German decree of April 26, 1941, Jews were forbidden to have contact with non-Jews, either as clients or professionals. This rift emerged at a time when the horror had only just begun. Regina suffered it either directly or indirectly through her family. Several further decrees were pronounced, but one of the most painful was surely the ninth, on July 8, 1942. According to this ruling, Jews could no longer frequent restaurants, cafés, entertainment establishments, swimming pools or beaches. It was no longer a question of living, but of surviving, what with the restrictions, requirements and persecution. For example, as a result of the ninth decree, Jews could only go to hairdressing salons between 3pm and 4pm[11].

It was in this context that the “final solution” came into being, based on decisions taken on January 20, 1942 at the German conference in Wannsee.

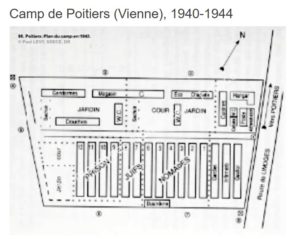

It was also in this context that the Bernstein family survived and Regina grew up. Additionally, on June 22, 1940, France was split in two by a demarcation line. Niort being in the Occupied Zone, the provisions were more drastic than those in the Free Zone, such as the requirement for people over the age of six to wear the yellow star as of May 29, 1942. However, the worst was yet to come. The real horror began with the roundups, starting with those of July 1942, including the Vél d’Hiv roundup on July 16 and 17. Soon afterwards, the deportations began. Little by little, these roundups spread outside the Paris region and eventually reached Niort. Very early in the morning of October 9, 1942, Régina’s entire family was arrested[12]. 143 people from Deux-Sèvres, including the Berstein family, were rounded up in July 1942. From September 27, 1940, they had all been required to take part in a census, on the instructions of the occupying forces, in order to be eligible for food vouchers. A memorial stone was inaugurated in February 2012, at the corner of Rue des Trois-Coigneaux, near to Niort station, in remembrance of all the Jews deported from Deux-Sèvres[13]. The roundup led by Kommandeur Harold[14] thus required the assistance of the French police and gendarmerie, as well as checking the registers at the prefecture[15]. was told in advance about the operation, which was part of the “final solution”. The October roundups affected not only the Deux-Sèvres department but the whole of the Poitou region. They targeted foreign and stateless Jews, including Czechoslovakians. Regina, her parents, brothers and sisters were taken to the transit camp at Poitiers[17], which was on the main N147 Limoges to Poitiers road, and was known as the “camp on the Limoges road”[18]. Living conditions there were horrendous, with a shortage of space, a lack of food, and the spread of various diseases[19].

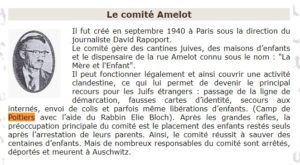

The three younger children, Simon, Regina and Bernath were released due to their being “French” thanks to the intervention of Rabbi Elijah Bloch. This rabbi,who was in charge of the UGIF in Poitiers, did not have official access to the camp. However, thanks to Marcelle Valensi, who worked in the camp under the cover of the Red Cross, he was able to access the camp in secret. In reality, Ms. Valensi was working for the association “le comité Amelot“, or “Amelot Committee”, which operated legally but also covertly, particularly where the rescue of children was concerned[20]. This access took the form not only of delivery of letters and parcels but also communication with the internees via Madame Valensi and Father Fleury, the Catholic chaplain who celebrated mass in the Gypsy camps and who also passed secretly through the section reserved for Jews. The rabbi’s role within the UGIF enabled him to negotiate with the authorities[21]. He became increasingly well known among the Jews in the region, which was unsurprising given that he was a man with such a big heart.

The three children Regina, Simon and Bernath were thus released, as were 195 others. 88 were placed in UGIF homes, of whom 53 were rounded up in 1944. The remaining children were placed with non-Jewish families. We do not know whether the Bernstein children were all placed with the same family or with three different families. At present, the names of the righteous who took them in during this time are not known, even though some registers are held in the Yad Vashem Memorial Center and the Shoah Memorial in Paris. They were most likely Christian families belonging to Catholic (in the Deux-Sèvres department) or Protestant (in the whole of Poitou region) pastoral networks[22].

The orphanage at La Varenne-Saint-Hilaire

In the registers we sometimes find “Régine” rather than “Régina”, although her true first name really was “Régina”. It is not surprising, however, to see her first name changed. No doubt she changed her identity in the hope of escaping the roundups, and perhaps this change took place during the period when she was staying with the Righteous. His brother Bernath also underwent a change of identity, taking the name Bernard. These changes of first name, where the new names were not very different from the real ones, gave these young children a better chance of remaining hidden and kept them safer, yet were not too abrupt[23]. The months following the placement of the children, including then five-year-old Regina, remain shrouded in mystery. We do not know who took them in, where, and whether they stayed together or not. These families were perhaps a refuge, a temporary haven of peace or, conversely, a violent environment[24]. The only thing that is certain is that these siblings, even at a very young age, must never have stopped thinking about their parents and other siblings. Perhaps Régina had visited them at the camp before they were transferred to Drancy. No doubt they were still hoping to return to their homes as they had been in the past. Unfortunately, this would no longer have been possible, as of November 1942, due to the escalation of the Holocaust.

From 9 October 1942 to 16 October 1942 the Bernstein couple and their three oldest children were interned in Poitiers, in the Limoges road camp. They left on the morning of October 16, 1942 at 4:30 a.m. on a train from Poitiers station to Drancy[25]. They left the horror of the transit camp only to be taken to the antechamber of death. They traveled in cattle cars, with 620 Jews on board the same train. It goes without saying that the travelling conditions were unbearable: cold, lack of space and insufficient air. From the roundup, to the convoy to Drancy, and then Auschwitz, the entire operation was carried out by the Sipo-SD. This was the same body that had ordered Louis Bourgain, the regional prefect at Poitiers, to send them the prefectural registers and also to assemble the Jews in camps such as the one in Poitiers. The Jews were allowed to take only two blankets, two pairs of shoes and a little food as well as the basic toiletries. The Bernstein family left Drancy for Auschwitz on November 6, 1942 on board Convoy 42[26] and were probably killed at Auschwitz on November 11, 1942[27].

Regina and her brothers escaped that ordeal but were not impervious to it, as the rest of their story proves. Despite having been released from the Limoges road camp, these three children, like many others in the same situation, were said to be “blocked”. Their names were listed in registers held by the German occupying forces[28]. As a result, some children were recaptured. Régina was interned once again at the Limoges road camp, alongside her brothers and some other children, on May 24, 1943. The intention was to place all these young Jews in UGIF centers (the UGIF had different branches, including one that managed children’s homes). Regina and her two brothers were thus assigned to the orphanage of La Varenne-Saint-Hilaire, near Paris. The children left the camp on the morning of May 26, 1943 and were taken by bus to Poitiers train station, accompanied by ten police officers. There they boarded a train, on which there was a Red Cross nurse to care of them. Finally, the children arrived in Paris where they were met by managers of the various children’s homes in the Paris area[29].

The roundup of 22 July 1944

Management of the orphanage at 30 rue Saint-Hilaire in La Varenne, had been transferred to the UGIF in December 194, as had all the Jewish children’s homes in the Paris region, and it was thus accessible to the German occupying forces. For Regina, this orphanage would have been a peaceful bubble amidst the horror of the war. To be more specific, there was a joyful atmosphere, a great friendship among the residents and above all a very strong bond between the staff and the children. This same dedicated group of staff was striving to give an “ordinary” childhood to these children who had been deeply wounded by the war. Even though the large dormitories of the orphanage might have been cold, there was always a certain warmth there. The food was reasonably good[30]. Even in this place of refuge, there was discrimination. For example, children had to wear the yellow star. Régina, who until then had never had to wear it, was obliged to put it on when she turned six years old[31].

Unfortunately, this happier interlude soon came to an end. The liberation of the capital was drawing near at the same time that the Allies, who had landed on June 6, 1944, were advancing towards it. Aloïs Brunner, commander of the Drancy camp, took advantage of the confusion to continue his murderous madness. He sent his commandos to the UGIF homes to round up the all the children in their registers. 250 children, including 18 babies, were rounded up, 28 of them from La Varenne. A commemorative plaque, erected in their memory, can be seen today at the Jewish community’s Hillel Center on the site of the former orphanage[32]. During the night of July 21-22, 1944, the children were torn from their sleep by the SS, who ordered their removal. The children, in total panic, refused to come down. The SS decided to shoot at the façade of the building. Eighteen children, including Regina and her brothers, left the orphanage scantily dressed and afraid, carrying a wretched bundle as their only belongings. They climbed onto buses bound for Drancy, accompanied by four staff members. A raid on the Zysman boarding house in La Varenne, removing ten children and two staff members, also took place that day. The children arrived in Drancy very shaken up[33]. The residents and camp staff improvised bedding for them on the stairs and beds riddled with bedbugs. The children were well disciplined, helped each other and obeyed instructions. The horrors of war had taught them to support each other, to be mature and to keep quiet.

Regina must surely have been part of this network that reassured her brothers and the other residents. She was six years old at the time and was nearing her seventh birthday, but this young soul had had to learn to grow up without her parents, in pain and happiness, however fleeting. Perhaps she was mature beyond her years. The children left Drancy for Auschwitz aboard Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. 1300 people, including 270 children, were deported on this convoy. July 31 marked the beginning of a horrific two-and-a-half-day journey to their deaths. The cattle cars were padlocked and people were crowded. It was no longer a question of living but of surviving in inhuman conditions: one small jar of drinking water, some tiny holes to let in air, one small bucket for everyone to use as a toilet, and stifling heat. Thirst and fear took hold of the children, but fortunately the accompanying staff sang traveling songs and songs of hope to soothe to send them to sleep, although they themselves were very thirsty and hot, having nothing left to swallow. The convoy arrived at Auschwitz on August 3, 1944A[34] The deportees disembarked onto the platform, and the SS proceeded to sort them into lines. The women and children were taken straight to the gas chambers[35]. Regina is presumed to have died on August 3. According to the Convoy 77 association’s documents, she was murdered on August 5[36]. Her life was taken after a little less than seven years, including two years of being separated from her parents and four years of being excluded, persecuted, discriminated against…

Biography written by Justine Martin-Billon, a 10th grade student at the Marguerite de Navarre high school in Bourges, France, under the supervision of Ms. Pavlina Dublé and Mr. Stanley Théry, her history and geography teachers.

Poem dedicated to Régina Bernstein and her two little brothers

Three sparks of hope in the darkness of the Holocaust

In the sombre light of a world sinking into a dark madness

In the distance, three innocent and shimmering souls appear.

In a haze of childhood uprooted and overwhelming,

Only shadows and dreams of deceptive hope remain.

These nascent lives, nurture the illusion that the war

Will emerge from its chrysalis, releasing

A beautiful dove bringing everlasting peace.

And last night, she dreamed of a new age.

At dawn these three beautiful spirits of love and unity

Sketch in their imagination, bathed in sunlight,

Inhumanity succumbing to all the wonders

Of their family reunion, of their cocoon.

Horror consumes these fine thoughts in a mirage.

This atrocity is the crime of men blinded

By an ideology, false, historical and rooted

In a sea of minds driven and deluded by rage.

These hybrids of villains and torturers have

Treated you like animals with a barbaric, absent heart

Losing their right to live, locking you up, killing you.

Only the remorse of this sacrifice remains.

Beneath this dark rain, a beautiful, eternal flame burns

That of altruism, of the goodness of true humankind.

From diverse origins, all have reached out to you.

At great risk, they saved you, beyond fraternity.

Like buds you have blossomed, and grown the nation

Like so many other Jews, enriched our land

Offering your values, the sincerest in the universe.

For infinity, out of oblivion, your three lives will shine.

Justine Martin–Billon

Notes

[1] Service Historique de la Défense (SHD), AC 21P 482 231, Acte de naissance de Régina Bernstein, Sedan, 9 décembre 1937 :

[2] Site Web de l’AJPN (Anonymes, Justes et persécutés de la période Nazie) sur les arrestations à Niort en 1939-1945 : http://www.ajpn.org/arrestation-1-79191.html <consulté le 14 mai 2020>.

Site Web du Mémorial de la Shoah : http://www.memorialdelashoah.org/ <consulté le 14 mai 2020>.

[3] SHD, AC 21P 482 230, Acte de naissance de Bernath Bernstein, Sedan, 25 juillet 1939 :

[4] Gutkowsk Hélène, De la France occupée à la Pampa, Paris, Le Manuscrit, 2017 (https://books.google.fr/books?id=rshKDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1931&lpg=PA1931&dq=Meilich+Ajzensztejn&source=bl&ots=5rZII5Gi3o&sig=ACfU3U2D4kH2rmUcBdGGiKxBkRUlvVx5jA&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiP9ezD1aTpAhWIz4UKHfXTATkQ6AEwAXoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=Sedan&f=false <consulté le 26 juin 2020>).

[5] Bauer Paul, « La Colonie tchécoslovaque en France de 1914 à 1940 », interview de Namont Jean-Philippe, Radio Prague International, 2011 (https://www.radio.cz/fr/rubrique/histoire/la-colonie-tchecoslovaque-en-france-de-1914-a-1940 <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

See also this Cairn Info article in English

[6] Gutkowsk Hélène, op. cit.

[7] Lévy Paul, Élie Bloch, Être juif sous l’Occupation, Paris, Geste Éditions, 1999, p. 1910-1911 et 1931 (https://books.google.fr/books?id=DmNYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT624&lpg=PT624&dq=rafle+9+octobre+1942+les+deux+s%C3%A8vres&source=bl&ots=S2zKt_G7VQ&sig=ACfU3U1_Wszty2g32o0WXs3yi6rIDyrplg&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjRpKGb5qTpAhVHA2MBHcEECFc4ChDoATAHegQICBAB#v=onepage&q=rafle%209%20octobre%201942%20les%20deux%20s%C3%A8vres&f=false <consulté le 26 juin 2020>).

[8] Site Web du Mémorial de la Shoah, notices de la famille Bernstein (http://ressources.memorialdelashoah.org/resultat.php?type_rech=rap&bool%5B%5D=&index%5B%5D=fulltext&value%5B%5D=bernstein&bool%5B%5D=AND&index%5B%5D=fulltext&value%5B%5D=&bool%5B%5D=AND&index%5B%5D=fulltext&value%5B%5D=&spec_date_naissance_start=&spec_date_naissance_end=&naissances_tous=&adresses_tous=&biographies_tous=&id_pers=*&spec_expand=1 <consulté le 15 mai 2020>)

[9] Béraut Jean-Marc, « Le Juif interdit de travail », Le Genre Humain, n°30-31, 1996, p. 209-229 (https://www.cairn.info/revue-le-genre-humain-1996-1-page-209.htm?contenu=resume <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

[10] Exposition « Traqués, cachés, sauvés. Être juif en Poitou (1940-1944) », Thouars, 12 janvier – 7 juin 2015, relayée par la Fondation pour la mémoire de la déportation (FMD) : https://fondationmemoiredeportation.com/2015/01/14/exposition-traques-caches-sauves-etre-juif-en-poitou-1940-1944/ <consulté le 29 juin 2020>.

[11] Laffitte Michel, « L’UGIF face aux mesures antisémites de 1942 », Les Cahiers de la Shoah, n°9, 2007, p. 123-180 (https://www.cairn.info/revue-les-cahiers-de-la-shoah-2007-1-page-123.htm <consulté le 26 juin 2020>).

[12] Kerouanton Sébastien, « Niort : l’hommage aux 143 déportés juifs », La Nouvelle République, 3 février 2012 (https://www.lanouvellerepublique.fr/deux-sevres/niort-l-hommage-aux-143-deportes-juifs <consulté le 15 mai 2020>).

Site Web de l’AJPN sur les arrestations à Niort en 1939-1945 : http://www.ajpn.org/arrestation-1-79191.html <consulté le 15 mai 2020>.

[13] Rouziès Jean, « Niort : une stèle à la mémoire des 143 Juifs déportés », La Nouvelle République, 30 janvier 2012 (https://www.lanouvellerepublique.fr/deux-sevres/niort-une-stele-a-la-memoire-des-143-juifs-deportes <consulté le 20 mai 2020>).

Site Web de Vivre à Niort : « Hommage aux 143 Juifs déportés des Deux-Sèvres », 3 février 2012 : https://www.vivre-a-niort.com/fr/actualites/dernieres-infos/hommage-aux-143-juifs-deportes-des-deux-sevres-2452/index.html <consulté le 20 mai 2020>.

[14] Yagil Limore, Désobéir : Des policiers et des gendarmes sous l’occupation, 1940-1944, Paris, Nouveau Monde Éditions, 2018 (https://books.google.fr/books?id=MGDHDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT161&lpg=PT161&dq=rafle+9+octobre+1942+les+deux+s%C3%A8vres&source=bl&ots=XcfiGTg1GC&sig=ACfU3U2UppBeGx647K25ISYjbeBg8Rperw&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjRpKGb5qTpAhVHA2MBHcEECFc4ChDoATABegQIChAB#v=onepage&q=harold&f=false <consulté le 31 août 2020>).

[15] Ibid. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=MGDHDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT161&lpg=PT161&dq=rafle+9+octobre+1942+les+deux+s%C3%A8vres&source=bl&ots=XcfiGTg1GC&sig=ACfU3U2UppBeGx647K25ISYjbeBg8Rperw&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjRpKGb5qTpAhVHA2MBHcEECFc4ChDoATABegQIChAB#v=onepage&q=rafle%209%20octobre%201942%20les%20deux%20s%C3%A8vres&f=false <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

Gutkowsk Hélène, op. cit. p. 1903-1918. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=rshKDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1931&lpg=PA1931&dq=Meilich+Ajzensztejn&source=bl&ots=5rZII5Gi3o&sig=ACfU3U2D4kH2rmUcBdGGiKxBkRUlvVx5jA&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiP9ezD1aTpAhWIz4UKHfXTATkQ6AEwAXoECAoQAQ#v=snippet&q=9%20octobre%201942&f=false <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

[16] Lévy Paul, Élie Bloch, op. cit. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=DmNYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT624&lpg=PT624&dq=rafle+9+octobre+1942+les+deux+s%C3%A8vres&source=bl&ots=S2zKt_G7VQ&sig=ACfU3U1_Wszty2g32o0WXs3yi6rIDyrplg&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjRpKGb5qTpAhVHA2MBHcEECFc4ChDoATAHegQICBAB#v=snippet&q=bourgain&f=false <consulté le 31 août 2020>).

[17] Lévy Paul, Élie Bloch, op. cit. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=DmNYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT624&lpg=PT624&dq=rafle+9+octobre+1942+les+deux+s%C3%A8vres&source=bl&ots=S2zKt_G7VQ&sig=ACfU3U1_Wszty2g32o0WXs3yi6rIDyrplg&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjRpKGb5qTpAhVHA2MBHcEECFc4ChDoATAHegQICBAB#v=snippet&q=9%20octobre%201942&f=false <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

Archives départementales des Deux-Sèvres, Ordre d’arrestation octobre 1942 : Première rafle en Deux-Sèvres ; source communiquée sur le site Web du Centre régional Résistance et Liberté de Thouars par Pouplain Jean-Marie, « La cache des Juifs en Deux-Sèvres, l’exemple du Noirvault », 2005 (https://www.crrl.fr/module-Contenus-viewpub-tid-2-pid-236.html <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

[18] Site Web de l’AJPN sur le Camp de la Route de Limoges : https://www.ajpn.org/internement-Camp-de-la-Route-de-Limoges-477.html <consulté le 20 mai 2020>.

Site Web du FMD sur le camp d’internement de Poitiers : http://www.bddm.org/int/details.php?id=73124&display=0 <consulté le 29 juin 2020>.

Site Web de l’Association philatélique de Rouen et agglomération sur une étude des camps d’internement français, en particulier celui de Poitiers : http://www.apra.asso.fr/Camps/Fr/Camp-Poitiers.html <consulté le 20 mai 2020>.

Site Web du Mémorial des Nomades de France sur le camp de Poitiers en 1940-1944, qui propose un plan du camp : http://memorialdesnomadesdefrance.fr/camp-de-poitiers-vienne-1940-1944/ <consulté le 20 mai 2020>.

[19] Lévy Paul, Un camp de concentration français, Poitiers (1939-1945), Paris, Sedes, 1995 (https://www.cairn.info/un-camp-de-concentration-francais–9782718192314.htm <consulté le 26 juin 2020>). Il décrit notamment les conditions de vie dans le camp de Poitiers selon la direction.

Lévy Paul, Élie Bloch, op. cit. : la femme d’Élie Bloch internée au camp décrit à son tour les conditions de vie au camp de Poitiers du point de vue des internés.

[20] Marrot-Fellag Ariouet Céline, Les enfants cachés pendant la seconde guerre mondiale aux sources d’une histoire clandestine, s. d., voir en particulier la partie 4 sur le Comité Amelot (https://lamaisondesevres.org/cel/cel2.html <consulté le 20 mai 2020>).

Exposition « Rue Amelot, Un réseau clandestin pendant la guerre », Paris 11e, 13-18 novembre 2006, relayée par l’association la Maison de Sèvres : https://lamaisondesevres.org/ame/amesom.html <consulté le 29 juin 2020>. Voir en particulier le témoignage de Jacoubovitch J., « Document : Rue Amelot » (https://lamaisondesevres.org/ame/ame1.html <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

Site Web de l’association Aloumim des enfants juifs cachés en France pendant la Shoah, qui présente notamment le Comité Amelot : http://www.aloumim.org.il/histoire/vocation-communautaire.html <consulté le 20 mai 2020>.

Lévy Paul, Un camp de concentration français, op. cit., qui témoigne de la libération des trois enfants Bernstein : https://books.google.fr/books?id=vcV2DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT151&lpg=PT151&dq=R%C3%A9gine+Bernstein+1937&source=bl&ots=1E9soI7Vl_&sig=ACfU3U364QFammA5VexOOEI0gK6hrjq_HQ&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwik6IuelJvpAhWNzIUKHZ2ZCbYQ6AEwC3oECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=R%C3%A9gine%20Bernstein%201937&f=false <consulté le 20 mai 2020>.

[21] Lévy Paul, Élie Bloch, op. cit. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=DmNYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT624&lpg=PT624&dq=rafle+9+octobre+1942+les+deux+s%C3%A8vres&source=bl&ots=S2zKt_G7VQ&sig=ACfU3U1_Wszty2g32o0WXs3yi6rIDyrplg&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjRpKGb5qTpAhVHA2MBHcEECFc4ChDoATAHegQICBAB#v=snippet&q=9%20octobre%201942&f=false <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

Cabanel Patrick, Histoire des Justes en France, Paris, Armand Colin, 2012 (https://books.google.fr/books?id=gGg0SziIzykC&pg=PT82&lpg=PT82&dq=l%27amiti%C3%A9+chr%C3%A9tienne+camps+de+Limoges&source=bl&ots=2htbIu8Yl6&sig=ACfU3U2ZdHWtoFaVbRv4QKaZeRW_ZSSE7g&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwimtI2owPrpAhVSyoUKHRBdAuUQ6AEwAXoECAoQAQ#v=snippet&q=Poitiers&f=false <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

[22] Lévy Paul, Élie Bloch, op. cit. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=DmNYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT624&lpg=PT624&dq=rafle+9+octobre+1942+les+deux+s%C3%A8vres&source=bl&ots=S2zKt_G7VQ&sig=ACfU3U1_Wszty2g32o0WXs3yi6rIDyrplg&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjRpKGb5qTpAhVHA2MBHcEECFc4ChDoATAHegQICBAB#v=snippet&q=justes&f=false <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

Semelin Jacques, Persécutions et entraides dans la France occupée, Paris, Les Arènes, 2013 (https://books.google.fr/books?id=0Xs4DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT472&lpg=PT472&dq=dispensaire+La+m%C3%A8re+et+l%27enfant+Rue+Amelot&source=bl&ots=YqRk4NZw0w&sig=ACfU3U3xmT8RTyKrXI6-i_8tbogzBTk4Xg&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjfzYKP2vzpAhVM3IUKHfyBDyUQ6AEwAXoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=Poitiers&f=false <consulté le 20 mai 2020>.

Exposition « Traqués, cachés, sauvés », op. cit. : https://fondationmemoiredeportation.com/2015/01/14/exposition-traques-caches-sauves-etre-juif-en-poitou-1940-1944/ <consulté le 29 juin 2020>.

[23] Sur le changement d’identité des enfants en clandestinité, voir la dernière partie de l’article de Zeitoun Sabine, « Accueil des enfants juifs étrangers en France et leur sort sous l’Occupation », Documents pour l’histoire du français langue étrangère ou seconde, 46, 2011 (https://journals.openedition.org/dhfles/2108 <consulté le 26 juin 2020>).

[24] Hazan Katy, « Enfants cachés, enfants retrouvés », Les Cahiers de la Shoah, n°9, 2007, p. 181-212 (https://www.cairn.info/revue-les-cahiers-de-la-shoah-2007-1-page-181.htm <consulté le 26 juin 2020>.

Laffitte Michel, op. cit.

[25] Site Web du FMD sur le camp d’internement de Poitiers : http://www.bddm.org/int/details.php?id=73124&display=0 <consulté le 29 juin 2020>.

Lévy Paul, Élie Bloch, op. cit. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=DmNYDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT624&lpg=PT624&dq=rafle+9+octobre+1942+les+deux+s%C3%A8vres&source=bl&ots=S2zKt_G7VQ&sig=ACfU3U1_Wszty2g32o0WXs3yi6rIDyrplg&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjRpKGb5qTpAhVHA2MBHcEECFc4ChDoATAHegQICBAB#v=snippet&q=16%20octobre%201942&f=false <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

[26] Base de données du mémorial Yad Vashem sur les victimes de la Shoah : https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=fr&fromDeportation=true&advancedSearch=true&deportation_value=5092615 <consulté le 20 mai 2020 >.

[27] La date de naissance des trois enfants tchécoslovaques ne correspond pas avec tous les autres registres proposés par les sites et mémoriaux : https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/affichTexte.do?cidTexte=JORFTEXT000035939408&categorieLien=id <consulté le 20 mai 2020>.

[28] Marrot-Fellag Ariouet Céline, op. cit., voir en particulier la partie 1 sur l’UGIF (https://lamaisondesevres.org/cel/cel2.html <consulté le 21 mai 2020>).

Gutkowsk Hélène, op. cit., témoignage de Maurice Ajzensztejn, p. 1903-1918. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=rshKDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA1931&lpg=PA1931&dq=Meilich+Ajzensztejn&source=bl&ots=5rZII5Gi3o&sig=ACfU3U2D4kH2rmUcBdGGiKxBkRUlvVx5jA&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiP9ezD1aTpAhWIz4UKHfXTATkQ6AEwAXoECAoQAQ#v=snippet&q=9%20octobre%201942&f=false <consulté le 20 mai 2020>).

[29] Lévy Paul, Un camp de concentration français, op. cit. (https://books.google.fr/books?id=vcV2DwAAQBAJ&pg=PT151&lpg=PT151&dq=R%C3%A9gine+Bernstein+1937&source=bl&ots=1E9soI7Vl_&sig=ACfU3U364QFammA5VexOOEI0gK6hrjq_HQ&hl=fr&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwik6IuelJvpAhWNzIUKHZ2ZCbYQ6AEwC3oECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=26%20mai%201943&f=false <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

[30] Site Web de Amélineau Stéphane sur l’orphelinat de la Varenne : https://view.genial.ly/5e5a7a6c3ca5910fdcf62e45/presentation-les-orphelins-de-la-varenne-juillet-aout-1944 <consultés le 24 mai 2020>.

Site Web de la Communauté juive de la Varenne, présentant l’orphelinat : https://www.hillelweb.com/vie-cultuelle/synagogue/l-orphelinat/ <consultés le 24 mai 2020>.

[31] Marrot-Fellag Ariouet Céline, op. cit., voir en particulier la partie 1.1 « Les maisons d’enfants de l’U.G.I.F. » (https://lamaisondesevres.org/cel/cel2.html <consulté le 29 juin 2020>).

[32] Site Web de la Communauté juive de la Varenne, présentant l’orphelinat : https://www.hillelweb.com/vie-cultuelle/synagogue/l-orphelinat/ <consultés le 24 mai 2020>.

SHD, AC 21P 482 231, Plaque commémorative en l’hommage des enfants de l’orphelinat de la Varenne déportés après la rafle du 22 juillet 1944, figurant aujourd’hui dans le Centre Hillel de la Communauté juive de la Varenne :

SHD, AC 21P 482 231, Discours de Haver Nepthalie Wolf pour l’inauguration de la plaque commémorative le 22 avril 1990 :

SHD, AC 21P 482 231, Liste des enfants déportés de la Varenne réalisée par Nelly Wolf, où figurent Regina Bernstein et ses frères :

[33] Site Web « Mémoires des déportations, 1939-1945 », qui cartographie tous les camps du système concentrationnaire nazi : http://memoiresdesdeportations.org/fr/carte <consulté le 24 mai 2020>. Ici, le camp d’internement de Drancy :

[34] Site Web « Mémoires des déportations, 1939-1945 » : http://memoiresdesdeportations.org/fr/carte <consulté le 24 mai 2020>. Ici, le centre de mise à mort d’Auschwitz-Birkenau, avec détail du Crématorium K II en exemple.

[35] Site Web de Yad Vashem, Historique du convoi 77 : https://deportation.yadvashem.org/?language=fr&itemId=5092649 <consulté le 20 mai>.

[36] SHD, AC 21P 482 231, Documents récapitulant le parcours de Régina Bernstein :

Français

Français Polski

Polski