Died for France

A PARISIAN ARTISAN

Marcel Bereck was born on June 16, 1903, in the 12th district of Paris. His birth was registered on June 18 at the town hall of the 4th district. He was the son of Meyer Bereck and Rosine Gomulka, both of whom were born in Paris, were cap makers and lived at 23, rue Pasteur in Pantin, in the Seine department of France. His mother, who was by then a street trader and living on rue de la Roquette in Paris, died in 1919, when Marcel was still in his teens.

In 1923, Marcel did his national service.

At the age of 25, he married Raymonde Tilles on March 1, 1928, at the town hall of the 16th district of Paris. His wedding was mentioned in the newspaper L’Univers israélite1, (The Jewish Universe) and the religious ceremony was held at the synagogue on rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth in the 3rd district. Marcel’s father was listed as “missing”.

Raymonde Tilles was 17 years old2, and they lived at 141 avenue Victor-Hugo, in the 16th district. When they got married, Marcel was working as a silk merchant. The couple divorced on April 17, 1940.

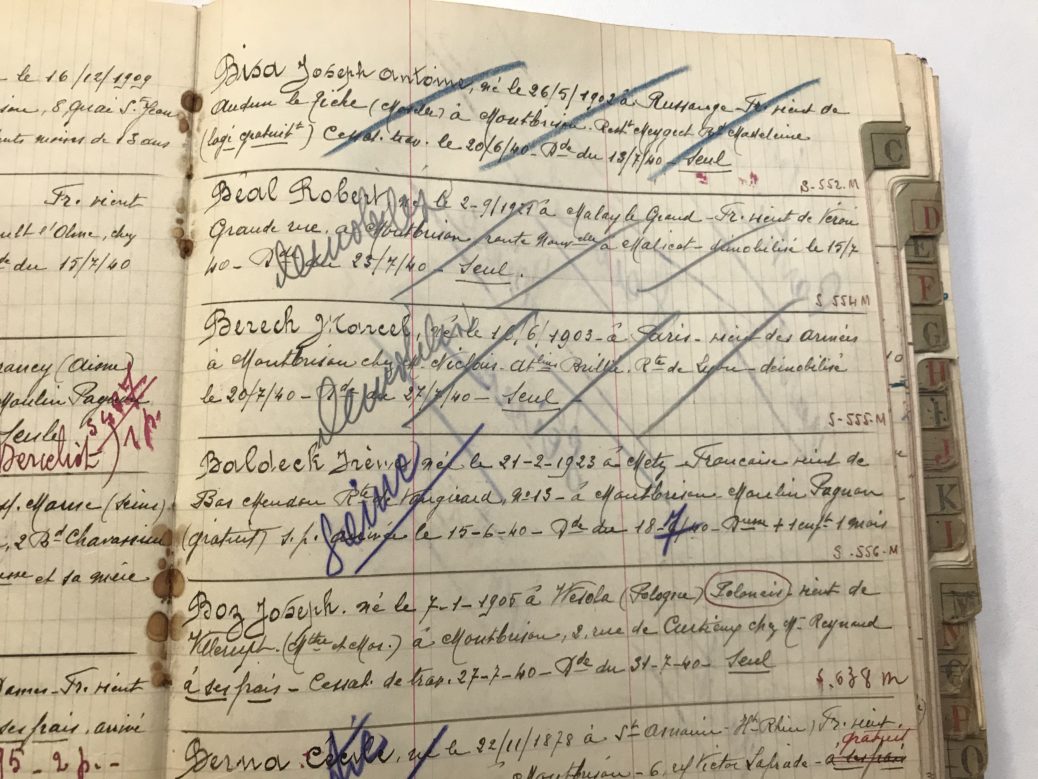

In September 1939, when war was declared, Marcel was called up. After the Armistice, he ended up, we do not how or why, in the Non-Occupied Zone (the so-called No-No zone) in a town called Montbrison, a sub-prefecture of the Loire department. In a register held in Montbrison, it says:

“Berech Marcel, born on 16/6/1903 in Paris came out of the armed forces, staying in Montbrison with Mr. Niclais, at Brillié workshops. Rte de Lyon. Demobilized on 7/20/40. Dde as of 27/7/40. Single.3”

At that time, therefore, he was living with the brother or father of his future wife, Suzanne, who he married on December 24, 1940. Suzanne Niclais was described as a seamstress, born in the 20th district of Paris on January 16, 1907, living in Montbrison and having previously lived in Moingt (?). Marcel, a “dressmaker”, was then living, as was his wife, on rue Saint-Jean in Montbrison4. This street was a extension of Route de Lyon, where the Brillié firm was situated, about ten minutes away on foot.

The Brillié company, founded in 1898 in Levallois-Perret, moved to Montbrison in the early 20th century. It was a well-known manufacturer of industrial clocks:

“As the First World War was looming, the company sought to establish itself in the center of France. A foreman, Marcel Cornut, found an old mill in Montbrison, on the impasse de l’Abbaye, and converted it into a workshop. During the 1914-1918 war, this factory manufactured clocks, as well as parts for weapons. After the armistice, the business was moved back to the Paris region, but Mr. Cornut stayed on in Montbrison. He founded his own company there.

Brillié pursued its innovative approach. On February 14, 1933, the company unveiled the first optical talking clock at the Paris Observatory, with the unforgettable words: “At the 4th stroke, it will be exactly…”. Orders arrived from all over the world. At the same time, the liner Le Normandie was equipped with Brillié precision instruments. In 1939, the Second World War brought the company back to Montbrison. Some of the managers of Jewish origin went to seek refuge there [our underlining]. After the Liberation, Brillié kept its two sites in Lavallois and Montbrison5.”

The site where the factory was located has now been redeveloped with several new buildings, including a school, the École Brillié.

Marcel Bereck last lived at 34, boulevard Chavassieu in Montbrison, in the Loire department, before being placed under house arrest at the Mondon Hotel in Saint-Jean-Soleymieux as from in 1942, as reported by Gérard Aventurier in an article published in 20106:

“A typical example of house arrest is that of Marcel Bereck, a garment maker, who lived at 34, boulevard Chavassieu in Montbrison. He was required to stay in the village of Saint-Jean-Soleymieux.” This village, the administrative center of the district, was about twelve miles from Montbrison, in the Monts du Forez area, which bordered the Puy-de-Dôme department.

The anti-Semitic persecution, as well as his commitment to the Resistance, turned Marcel Bereck’s life upside down.

A MEMBER OF THE RESISTANCE

Marcel Bereck joined the Resistance at the end of 1941 and reached the rank of captain in the FTPF (Francs-tireurs et partisans français) and was approved by the national commission on June 13, 1946 as captain in the FFI (Forces françaises de l’Intérieur)7. Captain Bereck, known as Bailly, is mentioned as having been in the intelligence service at the headquarters of the FTPF of the Loire from October 1, 1943 to January 1, 19448. He was also known as Lucie. Marcel Bereck is next listed as a fighter in the Vaillant-Couturier Battalion of the FTPF of the Loire “from January 1, 1944 to April 29 1944”9. A certificate from the Association nationale des Anciens Combattants des Forces Française d’intérieur Francs-Tireurs et Partisans Français et de leurs Amis, in Paris, October 3, 1950 states:10 :

“Member of the FTP in February 1942; organized the first maquis [resistance group], transported weapons for the resistance groups of Montbrison in 1942, formed the Pépin maquis in October 1942. Later transferred to the Puy de Dôme to perform the same role, he was arrested on April 29 [?], 1944 in Clermont-Ferrand (RV discovered by the Gestapo on a member of the FTP who had been arrested earlier).”

Camp Pépin ( the FTPF used the term “camp” to refer to their maquis resistance groups) was set up in the Monts du Forez, in the village of Roche, now Roche-en-Forez. A man called Jean Favre (1910-1991) was in charge of “reassembling the Pépin camp in the Monts du Forez, which he called the “plateau de Gourgon”. The camp had been dispersed by a GMR (Groupe Mobile de Réserve)11, a month earlier. He was in charge of Camp Pépin from December 1943 to March 194412”.

As regards this specific GMR attack:

“On December 31, a police operation involving about fifty police officers, thirty Guardsmen and about twenty GMRs was carried out west of the village of Roche 13. The jasserie of Gourgon, the place where the suspects were reported to be, and the hamlet of Glisieux, the group’s supply center, were searched. No terrorists were discovered, but provisions and a notebook “containing information on the composition of the group” were confiscated. This notebook, which came from a stationery shop in Saint-Etienne, bore a list of thirteen first names accompanied by identification numbers: 13526 Robert, 13527 Jacques, 13528 Jeannot, etc.14 These names were accompanied by abbreviated dates from mid-October to the beginning of December 1943, the earliest dates corresponding to the first registration numbers. This type of coding is characteristic of the FTP. A “maquis song” had also been hastily written in the notebook, with crossings-out and rewrites: it would seem that it was still unfinished. There were also some instructions, passwords, etc.”15

The Vichy forces attacked the Pépin maquis group, whose high-altitude location must have made life difficult for the volunteers who were there under instructions of Marcel Bereck, and later Jean Favre: the Roche Gourgon is over 4600 feet (1420 m) high, and the Pic de Glizieux is 4120 feet (1256 m). At least one other maquis group based in the same area gave up due to bad weather during the winter of 1943-1944.

An FFI membership certificate, issued in Lyon on October 8, 1951 says of Marcel16 : “FTPF Loire from January 1, 1944 to April 29, 1944: Was in command of an FTP company that was part of a unit commanded by Major Charles.”

At that time, when maquis groups of various types were being formed in the Loire, particularly in the Monts du Forez area, contacts were established between them, either to exchange information, to coordinate activities or to acquire weapons, which the FTPF often lacked. A statement confirms this with regard to Marcel Bereck17 :

“Captain Boirayon Antoine, commander of the ANGE group of the intelligence corps, certifies that Mr. Bereck served in the Resistance and was in contact with the Ange group from the beginning of 1943 until the date of his arrest. Issued in Montbrison on July 29, 1945.”

The Ange-Buckmaster maquis group and network were very active in the Loire region and were dependent on the British Special Operations Executive. Well-supplied with weapons dropped by parachute, the Ange group distributed weapons to other networks and maquis groups. It also organized joint operations with other groups, including communists, which may explain the certificate received from the SOE by Marcel Bereck. The GMR, aided by the Germans, attacked Ange group, the Secret Army and the FTP on August 7, 1944 at Lérigneux, near Roche. Antoine Boirayon was the leader of the Ange group. In a joint effort, these groups of quite different origins fought off the GMR.

It was during this eventful period that Marcel Bereck disappeared from the village in which he was staying under house arrest18 : “On April 14, 1944, Marcel Bereck informed the owner of the Mondon Hotel in Saint-Jean-Soleymieux that he was leaving to pick up his wife and two children in Montbrison and that he would come back the next day. He did not return to the area.”

This date corresponds to the time when Marcel transferred from the FTPF of the Loire to that of the Puy-de-Dôme. Unfortunately, however, his days of freedom were numbered.

ARREST, DEPORTATION AND DEATH

Ten days or so after his disappearance from Saint-Jean-Soleymieux, Marcel was arrested at the station in Clermont-Ferrand:19

“Arrested on a mission in Clermont-Ferrand following an appointment to which he had gone […] was denounced and arrested at the Clermont station on April 28,20 1944.”

Was he really turned in? A source mentions a note with the appointment written on it found on a Resistance fighter arrested shortly before him.

Having been identified as a Jew, Marcel was sent to Drancy camp, where he arrived on July 6, 1944. Two record sheets can be found in the archives, one purple and the other yellow. The yellow one mentions his occupation, “carpenter” and the address 25 rue Marie-Anne Colombier in Bagnolet. The purple one gives his address in Montbrison. They also mention that he had arrived from Compiègne. The search record made when he arrived at the camp says that he had only 23 francs on him.

Three weeks after he arrived in Drancy, Marcel Bereck was deported on Convoy 77, which left Bobigny railroad station for Auschwitz-Birkenau on July 31, 1944.

Marcel Bereck was interned in the Auschwitz camp, where he was tattooed with the number B-3685. He was then transferred to the Strutoff camp, then to the Echterdingen annex camp, and finally to the Vaihingen/Enz camp, which was even tougher than the others. On January 9, 1945, 50 sick prisoners from the Echterdingen camp, followed by about 50 others, were transferred to the camp for the sick and the dying at Vaihingen/Enz, not far from Stuttgart. At least 74 of them died there:21

“At the end of October 1944, […] the camp was transformed into an “SS camp for the sick and convalescent” which officially began operating on December 1. […] On November 10, the first train of patients from the “desert” camps arrived. Among them were Russians, Poles, French, Italians, Greeks, Belgians, Dutch, Norwegians, Germans – in all, prisoners of 20 different nationalities. They were completely abandoned to their fate, without sufficient food and with no heating in the barracks. The German camp doctor was totally uninterested in their condition.

Even after the arrival of two additional doctors from Neckarelz in January 1945, the situation did not improve. The doctors were desperately short of equipment and medicines. A transport of prisoners from Haslach on February 16 triggered an epidemic of typhoid fever, which caused up to 33 deaths per day and turned Vaihingen into a death camp. The last train with 144 prisoners from Mannheim-Sandhofen arrived in Vaihingen on March 11.”22

The camp was then evacuated by the SS shortly before the French troops arrived:

“At the beginning of April, the order was given to evacuate the camp. Two trains took those who were still able to walk to Dachau, where there were 515 men. The liberation of the camp by French troops took place on April 7. The French army doctor, Dr. Rossi, estimated that 650 survivors remained in the Vaihingen camp and were immediately transferred: on April 9 and 10, 73 French, Dutch and Belgian prisoners were transferred to Speyer, and on April 13, the Poles, Russians and Germans were transferred to Neuenbürg, near Bruchsal, where they were quarantined until the beginning of June.

126 former prisoners, whose condition prevented them from being transferred, were admitted to the hospital in Vaihingen, together with 60 other prisoners from Neuenburg. By the end of the year, 84 of them had died and were buried in the Vaihingen cemetery.

To avoid an epidemic, the camp barracks were burned immediately after they were evacuated on April 16.”

It was during this period, after the camp had been liberated by French army troops, that Marcel Bereck, then registered under the number 42937, died in mid-April 1945, as described by an eye witness:

“I, the undersigned, Guy Faucheux, living at 23 rue du Parc, Orléans, knew Mr. Bereck Marcel at the Vaihingen camp; when the camp was liberated, I had him taken to the Vaihingen hospital by the French troops and medical service. He was treated there for several days. In spite of the care given, he died there. His body lies in the cemetery at Kleinglattbarck [Kleinglattbach, a village a few miles from Vaihingen]. Not being able to give the exact time (sic) of his death, I would put it between April 15 and 20, 1945. Orléans, June 25, 1946.”23

Marcel’s Resistance information sheet corroborates this account: “Participated in numerous operations against the enemy, was arrested on April 19, 1944 in Clermont-Ferrand by the Gestapo, interned in Birkenau and Strutoff and then in the camp of Wanhingen, died of typhus and ill treatment.”24

A certificate from the hospital in Vaininghen/Enz dated October 18, 1946 gives the date of death as June 10, 1945.

Marcel’s body was exhumed from the Kleinglattbach cemetery in 1946 and transferred to the military section of the new cemetery in Bagnolet25. His name appears on the monument to the dead of Montbrison, in the Allard gardens, on the plaque for those who ” Died for France since 1939 “.

His widow, Suzanne Bereck, undertook the long and tedious formalities to have Marcel recognized as a Deported Resistance member. He was eventually “approved” as an FFI (French Forces of the Interior) and DIR (Deported and Interned Resistance fighter).

In the immediate post-war period, on February 7, 1946, his widow was living a with Mrs. Legendre at 89 (?) rue Dulong in the 17th district of Paris. In August 1949, and again in 1951, when she applied for the status of Deported and Interned Resistance fighter, she was living at 12 avenue Dianoux in Asnières, in the Seine department.

Marcel Bereck had two daughters, Anny Bereck and Rolande Gourbil26.

1 L’Univers israélite, 2 mars 1928.

2 Raymonde Tilles was also involved in the Resistance, was deported, and was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor. Le Monde, 16 July, 2000.

3 Montbrison Municipal Archives.

4 Journal de Montbrison, 28 December, 1940, Montbrison Municipal Archives.

5 Le Progrès website, article dated 28 August 2016.

6 Résistance et déportation dans le Forez, Village de Forez, Montbrison, 2010.

7 DAVCC records: 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015, and Vincennes military archives: GR 16 P 49196.

8 Mémoire des Hommes website.

9 Mémoire des Hommes website.

10 DAVCC records: 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

11 The GMR were the Mobile Reserve Groups, paramilitary units created by the Vichy government, under the control of René Bousquet. From the autumn of 1943, with the agreement of the Germans, they carried out attacks against the maquis resistance groups.

12 Biographical note on Jean Favre in the Maitron dictionary, online.

13 Report by Squadron Leader Bechet of January 2, 1944 – German Police – Relations and correspondence with the Germans – 112 W 85 – ADL, in Pascal Chambon, La Résistance dans le département de la Loire, 1940-44, De Borée, 2016, pp.315-316.

14 Préfecture – Sabotage and explosives (1943-44) – 2 W 28 – ADL in Pascal Chambon, La Résistance dans le département de la Loire, 1940-44, De Borée, 2016, p. 315-316.

15 Pascal Chambon, La Résistance dans le département de la Loire, 1940-44, De Borée, 2016, p. 315-316.

16 DAVCC records 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

17 DAVCC records 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

18 Gérard Aventurier, article cited.

19 DAVCC records 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

20 Another sources mentions 19th Avril.

21 Thomas Faltin, Im Angesicht des Todes, Das KZ Echterdingen und der Leidensweg de 600 Häftlinge, (editor’s note: Facing death: the Echterdingen annex camp and the ordeal of its 600 prisoners), édition Filderstadt/Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2008, p. 134, cited in the text of Volker Mall.

22 Site internet de L’association Mémorial du camp de concentration Vaihingen/Enz .

23 Volker Mall, Mémorial du camp annexe de Hailfingen-Tailfingen, 2017, translated by the Convoy 77 association.

24 DAVCC records 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

25 Photograph of the grave on the Généanet website

26 Information provided by Laurence Klejman.

Died for France

A PARISIAN ARTISAN

Marcel Bereck was born on June 16, 1903, in the 12th district of Paris. His birth was registered on June 18 at the town hall of the 4th district. He was the son of Meyer Bereck and Rosine Gomulka, both of whom were born in Paris, were cap makers and lived at 23, rue Pasteur in Pantin, in the Seine department of France. His mother, who was by then a street trader and living on rue de la Roquette in Paris, died in 1919, when Marcel was still in his teens.

In 1923, Marcel did his national service.

At the age of 25, he married Raymonde Tilles on March 1, 1928, at the town hall of the 16th district of Paris. His wedding was mentioned in the newspaper L’Univers israélite1, (The Jewish Universe) and the religious ceremony was held at the synagogue on rue Notre-Dame de Nazareth in the 3rd district. Marcel’s father was listed as “missing”.

Raymonde Tilles was 17 years old2, and they lived at 141 avenue Victor-Hugo, in the 16th district. When they got married, Marcel was working as a silk merchant. The couple divorced on April 17, 1940.

In September 1939, when war was declared, Marcel was called up. After the Armistice, he ended up, we do not how or why, in the Non-Occupied Zone (the so-called No-No zone) in a town called Montbrison, a sub-prefecture of the Loire department. In a register held in Montbrison, it says:

“Berech Marcel, born on 16/6/1903 in Paris came out of the armed forces, staying in Montbrison with Mr. Niclais, at Brillié workshops. Rte de Lyon. Demobilized on 7/20/40. Dde as of 27/7/40. Single.3”

At that time, therefore, he was living with the brother or father of his future wife, Suzanne, who he married on December 24, 1940. Suzanne Niclais was described as a seamstress, born in the 20th district of Paris on January 16, 1907, living in Montbrison and having previously lived in Moingt (?). Marcel, a “dressmaker”, was then living, as was his wife, on rue Saint-Jean in Montbrison4. This street was a extension of Route de Lyon, where the Brillié firm was situated, about ten minutes away on foot.

The Brillié company, founded in 1898 in Levallois-Perret, moved to Montbrison in the early 20th century. It was a well-known manufacturer of industrial clocks:

“As the First World War was looming, the company sought to establish itself in the center of France. A foreman, Marcel Cornut, found an old mill in Montbrison, on the impasse de l’Abbaye, and converted it into a workshop. During the 1914-1918 war, this factory manufactured clocks, as well as parts for weapons. After the armistice, the business was moved back to the Paris region, but Mr. Cornut stayed on in Montbrison. He founded his own company there.

Brillié pursued its innovative approach. On February 14, 1933, the company unveiled the first optical talking clock at the Paris Observatory, with the unforgettable words: “At the 4th stroke, it will be exactly…”. Orders arrived from all over the world. At the same time, the liner Le Normandie was equipped with Brillié precision instruments. In 1939, the Second World War brought the company back to Montbrison. Some of the managers of Jewish origin went to seek refuge there [our underlining]. After the Liberation, Brillié kept its two sites in Lavallois and Montbrison5.”

The site where the factory was located has now been redeveloped with several new buildings, including a school, the École Brillié.

Marcel Bereck last lived at 34, boulevard Chavassieu in Montbrison, in the Loire department, before being placed under house arrest at the Mondon Hotel in Saint-Jean-Soleymieux as from in 1942, as reported by Gérard Aventurier in an article published in 20106:

“A typical example of house arrest is that of Marcel Bereck, a garment maker, who lived at 34, boulevard Chavassieu in Montbrison. He was required to stay in the village of Saint-Jean-Soleymieux.” This village, the administrative center of the district, was about twelve miles from Montbrison, in the Monts du Forez area, which bordered the Puy-de-Dôme department.

The anti-Semitic persecution, as well as his commitment to the Resistance, turned Marcel Bereck’s life upside down.

A MEMBER OF THE RESISTANCE

Marcel Bereck joined the Resistance at the end of 1941 and reached the rank of captain in the FTPF (Francs-tireurs et partisans français) and was approved by the national commission on June 13, 1946 as captain in the FFI (Forces françaises de l’Intérieur)7. Captain Bereck, known as Bailly, is mentioned as having been in the intelligence service at the headquarters of the FTPF of the Loire from October 1, 1943 to January 1, 19448. He was also known as Lucie. Marcel Bereck is next listed as a fighter in the Vaillant-Couturier Battalion of the FTPF of the Loire “from January 1, 1944 to April 29 1944”9. A certificate from the Association nationale des Anciens Combattants des Forces Française d’intérieur Francs-Tireurs et Partisans Français et de leurs Amis, in Paris, October 3, 1950 states:10 :

“Member of the FTP in February 1942; organized the first maquis [resistance group], transported weapons for the resistance groups of Montbrison in 1942, formed the Pépin maquis in October 1942. Later transferred to the Puy de Dôme to perform the same role, he was arrested on April 29 [?], 1944 in Clermont-Ferrand (RV discovered by the Gestapo on a member of the FTP who had been arrested earlier).”

Camp Pépin ( the FTPF used the term “camp” to refer to their maquis resistance groups) was set up in the Monts du Forez, in the village of Roche, now Roche-en-Forez. A man called Jean Favre (1910-1991) was in charge of “reassembling the Pépin camp in the Monts du Forez, which he called the “plateau de Gourgon”. The camp had been dispersed by a GMR (Groupe Mobile de Réserve)11, a month earlier. He was in charge of Camp Pépin from December 1943 to March 194412”.

As regards this specific GMR attack:

“On December 31, a police operation involving about fifty police officers, thirty Guardsmen and about twenty GMRs was carried out west of the village of Roche 13. The jasserie of Gourgon, the place where the suspects were reported to be, and the hamlet of Glisieux, the group’s supply center, were searched. No terrorists were discovered, but provisions and a notebook “containing information on the composition of the group” were confiscated. This notebook, which came from a stationery shop in Saint-Etienne, bore a list of thirteen first names accompanied by identification numbers: 13526 Robert, 13527 Jacques, 13528 Jeannot, etc.14 These names were accompanied by abbreviated dates from mid-October to the beginning of December 1943, the earliest dates corresponding to the first registration numbers. This type of coding is characteristic of the FTP. A “maquis song” had also been hastily written in the notebook, with crossings-out and rewrites: it would seem that it was still unfinished. There were also some instructions, passwords, etc.”15

The Vichy forces attacked the Pépin maquis group, whose high-altitude location must have made life difficult for the volunteers who were there under instructions of Marcel Bereck, and later Jean Favre: the Roche Gourgon is over 4600 feet (1420 m) high, and the Pic de Glizieux is 4120 feet (1256 m). At least one other maquis group based in the same area gave up due to bad weather during the winter of 1943-1944.

An FFI membership certificate, issued in Lyon on October 8, 1951 says of Marcel16 : “FTPF Loire from January 1, 1944 to April 29, 1944: Was in command of an FTP company that was part of a unit commanded by Major Charles.”

At that time, when maquis groups of various types were being formed in the Loire, particularly in the Monts du Forez area, contacts were established between them, either to exchange information, to coordinate activities or to acquire weapons, which the FTPF often lacked. A statement confirms this with regard to Marcel Bereck17 :

“Captain Boirayon Antoine, commander of the ANGE group of the intelligence corps, certifies that Mr. Bereck served in the Resistance and was in contact with the Ange group from the beginning of 1943 until the date of his arrest. Issued in Montbrison on July 29, 1945.”

The Ange-Buckmaster maquis group and network were very active in the Loire region and were dependent on the British Special Operations Executive. Well-supplied with weapons dropped by parachute, the Ange group distributed weapons to other networks and maquis groups. It also organized joint operations with other groups, including communists, which may explain the certificate received from the SOE by Marcel Bereck. The GMR, aided by the Germans, attacked Ange group, the Secret Army and the FTP on August 7, 1944 at Lérigneux, near Roche. Antoine Boirayon was the leader of the Ange group. In a joint effort, these groups of quite different origins fought off the GMR.

It was during this eventful period that Marcel Bereck disappeared from the village in which he was staying under house arrest18 : “On April 14, 1944, Marcel Bereck informed the owner of the Mondon Hotel in Saint-Jean-Soleymieux that he was leaving to pick up his wife and two children in Montbrison and that he would come back the next day. He did not return to the area.”

This date corresponds to the time when Marcel transferred from the FTPF of the Loire to that of the Puy-de-Dôme. Unfortunately, however, his days of freedom were numbered.

ARREST, DEPORTATION AND DEATH

Ten days or so after his disappearance from Saint-Jean-Soleymieux, Marcel was arrested at the station in Clermont-Ferrand:19

“Arrested on a mission in Clermont-Ferrand following an appointment to which he had gone […] was denounced and arrested at the Clermont station on April 28,20 1944.”

Was he really turned in? A source mentions a note with the appointment written on it found on a Resistance fighter arrested shortly before him.

Having been identified as a Jew, Marcel was sent to Drancy camp, where he arrived on July 6, 1944. Two record sheets can be found in the archives, one purple and the other yellow. The yellow one mentions his occupation, “carpenter” and the address 25 rue Marie-Anne Colombier in Bagnolet. The purple one gives his address in Montbrison. They also mention that he had arrived from Compiègne. The search record made when he arrived at the camp says that he had only 23 francs on him.

Three weeks after he arrived in Drancy, Marcel Bereck was deported on Convoy 77, which left Bobigny railroad station for Auschwitz-Birkenau on July 31, 1944.

Marcel Bereck was interned in the Auschwitz camp, where he was tattooed with the number B-3685. He was then transferred to the Strutoff camp, then to the Echterdingen annex camp, and finally to the Vaihingen/Enz camp, which was even tougher than the others. On January 9, 1945, 50 sick prisoners from the Echterdingen camp, followed by about 50 others, were transferred to the camp for the sick and the dying at Vaihingen/Enz, not far from Stuttgart. At least 74 of them died there:21

“At the end of October 1944, […] the camp was transformed into an “SS camp for the sick and convalescent” which officially began operating on December 1. […] On November 10, the first train of patients from the “desert” camps arrived. Among them were Russians, Poles, French, Italians, Greeks, Belgians, Dutch, Norwegians, Germans – in all, prisoners of 20 different nationalities. They were completely abandoned to their fate, without sufficient food and with no heating in the barracks. The German camp doctor was totally uninterested in their condition.

Even after the arrival of two additional doctors from Neckarelz in January 1945, the situation did not improve. The doctors were desperately short of equipment and medicines. A transport of prisoners from Haslach on February 16 triggered an epidemic of typhoid fever, which caused up to 33 deaths per day and turned Vaihingen into a death camp. The last train with 144 prisoners from Mannheim-Sandhofen arrived in Vaihingen on March 11.”22

The camp was then evacuated by the SS shortly before the French troops arrived:

“At the beginning of April, the order was given to evacuate the camp. Two trains took those who were still able to walk to Dachau, where there were 515 men. The liberation of the camp by French troops took place on April 7. The French army doctor, Dr. Rossi, estimated that 650 survivors remained in the Vaihingen camp and were immediately transferred: on April 9 and 10, 73 French, Dutch and Belgian prisoners were transferred to Speyer, and on April 13, the Poles, Russians and Germans were transferred to Neuenbürg, near Bruchsal, where they were quarantined until the beginning of June.

126 former prisoners, whose condition prevented them from being transferred, were admitted to the hospital in Vaihingen, together with 60 other prisoners from Neuenburg. By the end of the year, 84 of them had died and were buried in the Vaihingen cemetery.

To avoid an epidemic, the camp barracks were burned immediately after they were evacuated on April 16.”

It was during this period, after the camp had been liberated by French army troops, that Marcel Bereck, then registered under the number 42937, died in mid-April 1945, as described by an eye witness:

“I, the undersigned, Guy Faucheux, living at 23 rue du Parc, Orléans, knew Mr. Bereck Marcel at the Vaihingen camp; when the camp was liberated, I had him taken to the Vaihingen hospital by the French troops and medical service. He was treated there for several days. In spite of the care given, he died there. His body lies in the cemetery at Kleinglattbarck [Kleinglattbach, a village a few miles from Vaihingen]. Not being able to give the exact time (sic) of his death, I would put it between April 15 and 20, 1945. Orléans, June 25, 1946.”23

Marcel’s Resistance information sheet corroborates this account: “Participated in numerous operations against the enemy, was arrested on April 19, 1944 in Clermont-Ferrand by the Gestapo, interned in Birkenau and Strutoff and then in the camp of Wanhingen, died of typhus and ill treatment.”24

A certificate from the hospital in Vaininghen/Enz dated October 18, 1946 gives the date of death as June 10, 1945.

Marcel’s body was exhumed from the Kleinglattbach cemetery in 1946 and transferred to the military section of the new cemetery in Bagnolet25. His name appears on the monument to the dead of Montbrison, in the Allard gardens, on the plaque for those who ” Died for France since 1939 “.

His widow, Suzanne Bereck, undertook the long and tedious formalities to have Marcel recognized as a Deported Resistance member. He was eventually “approved” as an FFI (French Forces of the Interior) and DIR (Deported and Interned Resistance fighter).

In the immediate post-war period, on February 7, 1946, his widow was living a with Mrs. Legendre at 89 (?) rue Dulong in the 17th district of Paris. In August 1949, and again in 1951, when she applied for the status of Deported and Interned Resistance fighter, she was living at 12 avenue Dianoux in Asnières, in the Seine department.

Marcel Bereck had two daughters, Anny Bereck and Rolande Gourbil26.

1 L’Univers israélite, 2 mars 1928.

2 Raymonde Tilles was also involved in the Resistance, was deported, and was made a Knight of the Legion of Honor. Le Monde, 16 July, 2000.

3 Montbrison Municipal Archives.

4 Journal de Montbrison, 28 December, 1940, Montbrison Municipal Archives.

5 Le Progrès website, article dated 28 August 2016.

6 Résistance et déportation dans le Forez, Village de Forez, Montbrison, 2010.

7 DAVCC records: 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015, and Vincennes military archives: GR 16 P 49196.

8 Mémoire des Hommes website.

9 Mémoire des Hommes website.

10 DAVCC records: 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

11 The GMR were the Mobile Reserve Groups, paramilitary units created by the Vichy government, under the control of René Bousquet. From the autumn of 1943, with the agreement of the Germans, they carried out attacks against the maquis resistance groups.

12 Biographical note on Jean Favre in the Maitron dictionary, online.

13 Report by Squadron Leader Bechet of January 2, 1944 – German Police – Relations and correspondence with the Germans – 112 W 85 – ADL, in Pascal Chambon, La Résistance dans le département de la Loire, 1940-44, De Borée, 2016, pp.315-316.

14 Préfecture – Sabotage and explosives (1943-44) – 2 W 28 – ADL in Pascal Chambon, La Résistance dans le département de la Loire, 1940-44, De Borée, 2016, p. 315-316.

15 Pascal Chambon, La Résistance dans le département de la Loire, 1940-44, De Borée, 2016, p. 315-316.

16 DAVCC records 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

17 DAVCC records 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

18 Gérard Aventurier, article cited.

19 DAVCC records 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

20 Another sources mentions 19th Avril.

21 Thomas Faltin, Im Angesicht des Todes, Das KZ Echterdingen und der Leidensweg de 600 Häftlinge, (editor’s note: Facing death: the Echterdingen annex camp and the ordeal of its 600 prisoners), édition Filderstadt/Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2008, p. 134, cited in the text of Volker Mall.

22 Site internet de L’association Mémorial du camp de concentration Vaihingen/Enz .

23 Volker Mall, Mémorial du camp annexe de Hailfingen-Tailfingen, 2017, translated by the Convoy 77 association.

24 DAVCC records 21 P 20194 and 21 P 424 015.

25 Photograph of the grave on the Généanet website

26 Information provided by Laurence Klejman.

Français

Français Polski

Polski