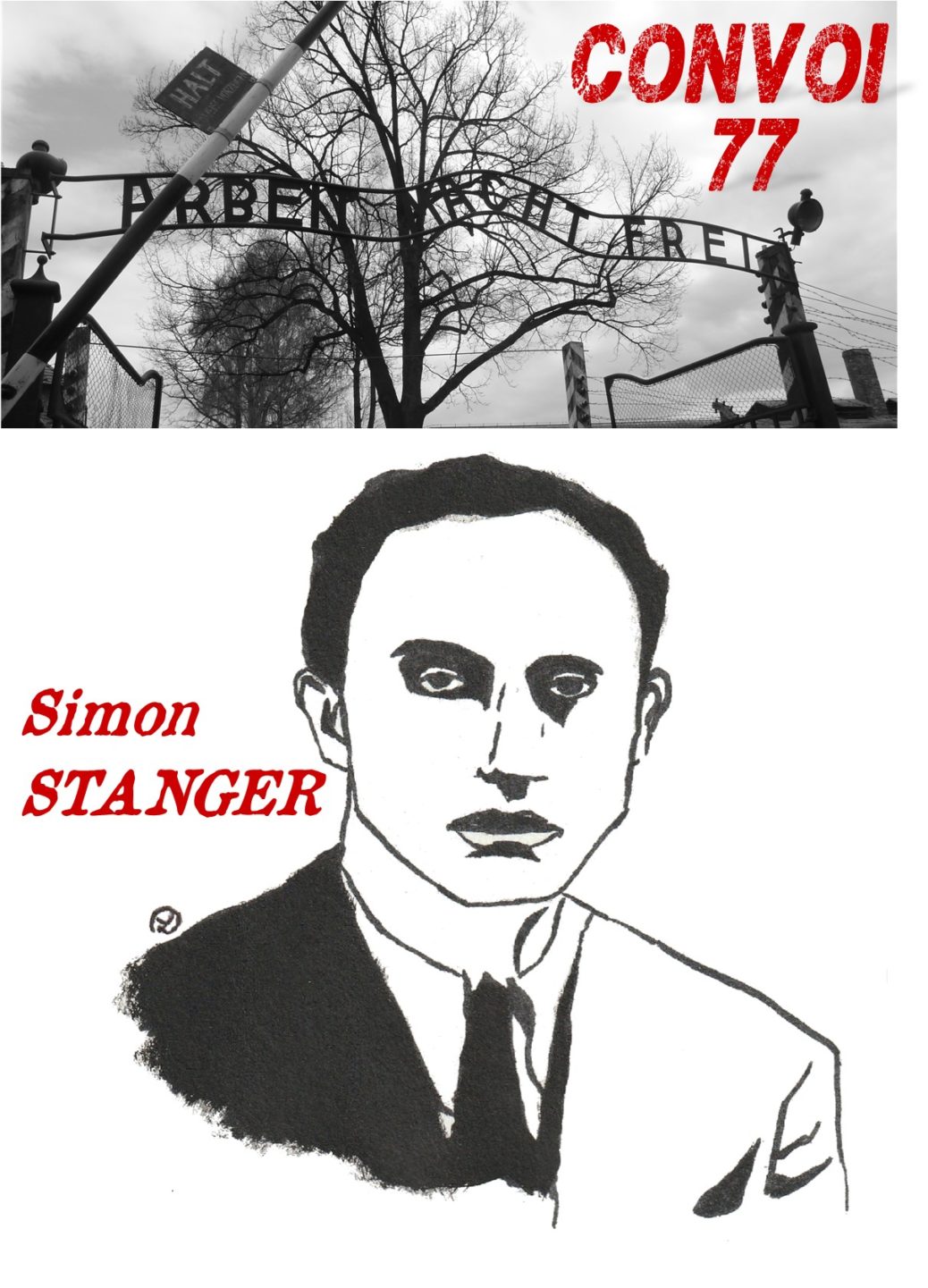

Simon STANGER

In memory of Simon

The story of a life

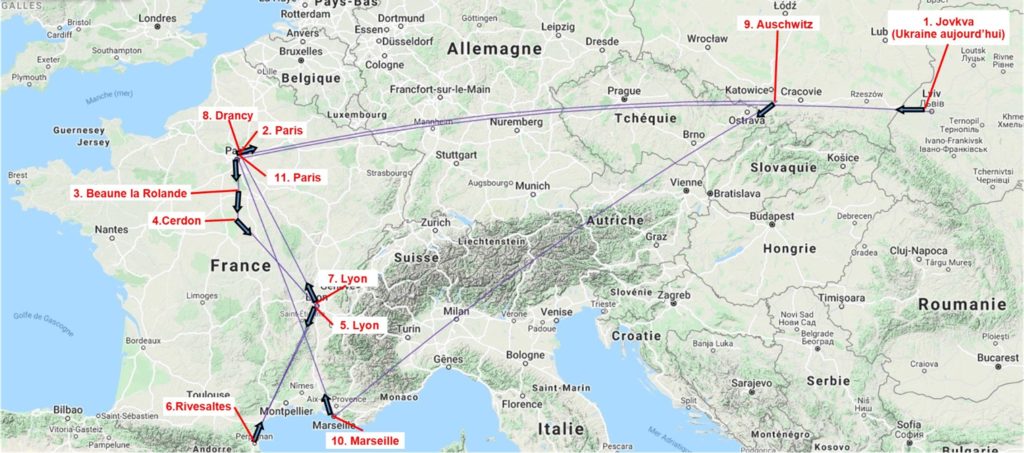

Having left Zolkiew, present-day Jovkva, in 1933, Simon moved to Paris. Then, in May 1941, he was arrested and interned in Beaune-la-Rolande camp. Next he was transferred to Cerdon, and while at the Matelotte farm at the end of July 1941, he managed to escape and sought refuge in Lyon. He was arrested twice. On the first occasion, in December 1941, he was eventually released. However, the second time, at the end of October 1942, he was interned in the Rivesaltes camp, near Perpignan. Once again he escaped and fled to Lyon. The Militia arrested him in June 1944. He was transferred to Drancy and deported to Auschwitz on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944. He was kept prisoner there and finally liberated in January 1945. He was repatriated to the Marseilles Center in the south of France and then returned to Paris on May 20, 1945.

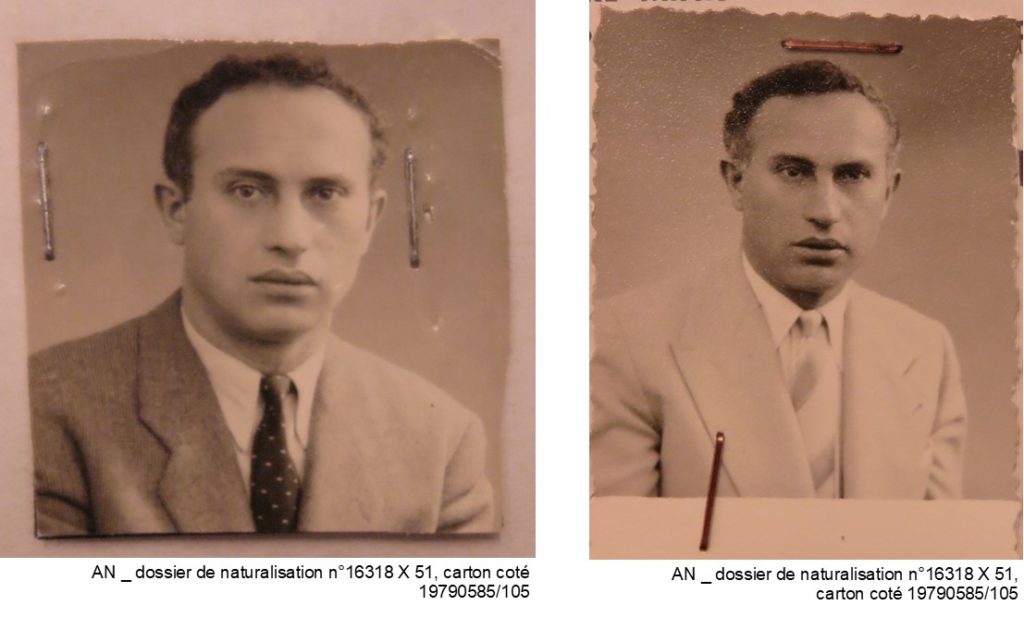

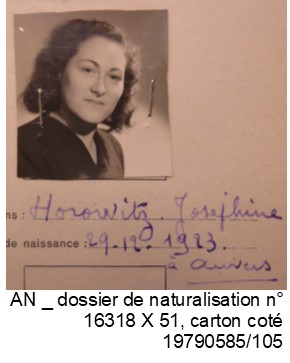

Photo from Simon’s application for French citizenship by naturalization, dossier No. 16318 X 51

Map showing Simon’s journey

Editor’s note

Two classes of 9th grade students, undeterred by the pandemic, set off on a historical exploration in 2020 at the start of a rather unusual school year. Under the guidance of two very committed teachers, Ms. Nathalie Berna and Ms. Marie Pourriot, the 51 students took their first steps as investigators to retrace the lives of people who were deported on Convoy 77: the young Berthe Aszer and a man called Simon Stanger. These two people had nothing in common except for being listed as “Jews” according to French and German laws in force in the summer of 1944, when their paths crossed.

Berthe Aszer was just 6 years old, and the students who undertook to write the biography of this young Holocaust victim soon drew a parallel with their own lives. It was the age at which they began second grade, which did not seem so long ago. They realized that she never had the opportunity to be as lucky as they were or to go to high school. When they first looked through the records available on the young deportee, they were immediately struck by the fact that while Berthe was murdered in Auschwitz on August 5, 1944, her official French death certificate was only issued on May 30, 2013. Why did it take almost seventy years for Berthe’s fate to be recognized once and for all by her country as a victim of the Holocaust? Or for it to be officially acknowledged that she had “Died for France”?

The students followed in the footsteps of a family of Polish Jews who emigrated to Metz, in France, where Berthe was born, and then moved to Paris when the war broke out and the eastern border regions were taken over by the Reich.

Meanwhile, the students also set about reconstructing the life of Simon Stanger. A young Polish Jew, who came to live in France, trusting in the French Republic, Simon was one of the first people, mainly men, to be affected by the anti-Jewish laws enacted by Philippe Pétain’s government. His story is that of a man who tried everything to survive the barbarity, escaping several times from French internment camps, and managing to survive and return from the extermination camps in Poland, in bad shape but ready to rebuild his life, which, as we will see, he did.

The students discovered “from the inside” what the anti-Jewish policies and round-ups really meant for people of all ages. This included the Vel d’Hiv round-up, during which Berthe and her parents were arrested, as well as the so-called “Green Ticket” roundup in May 1941, to which foreign Jews living in Paris, many of whom had volunteered to fight against the German troops, were summoned to go, and which Simon Stanger confidently attended. Before being sent to Drancy camp and being deported together, Berthe and Simon had already experienced, at different times, the camps in the Loiret department of France, the sad antechambers of the death camps, as were Drancy and Compiègne in particular.

The fruits of the students’ research are recorded in an illustrated journal where archived material and photos are used to enhance a vibrant and historically accurate narrative that provides readers with a body of knowledge that goes well beyond the biographies of Berthe and Simon.

Their investigations were meticulous and thorough. As a historian, I commend the work they have accomplished, despite the difficulties caused by public health crisis, by searching for and finding documents in the departmental and national archives, in books, at the Shoah Memorial in Paris and at Yad Vashem, in particular. They have thus greatly increased the limited information provided by the records held in Caen by the DAVCC (Division des Archives de Victimes des Conflits Contemporains au Service Historique de la Défense, the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service).

Their biographies, along with some of the photos and drawings by two of the students, will be posted on the Convoy 77 website. This historical project will be of use to everyone, but it is not hard to imagine that on a personal level, each student will have gained experience that will strengthen his or her sense of citizenship, and perhaps also a taste for history.

L. Klejman, historian, convoi 77

The beginning of our investigation

Introduction to the project

Our teachers, Ms. Berna and Ms. Pourriot, introduced us to the project in October 2020.

What is a convoy? Why was the transport that they were telling us about called Convoy 77?

We had all heard the word “Auschwitz” before, but when Ms. Pourriot told us that we were about to step into the life of a young man who had survived and returned from Auschwitz, we were speechless.

After everything we had been told about the Shoah, and everything we knew about the “Final Solution”, how did this man manage to come back, and still be alive?

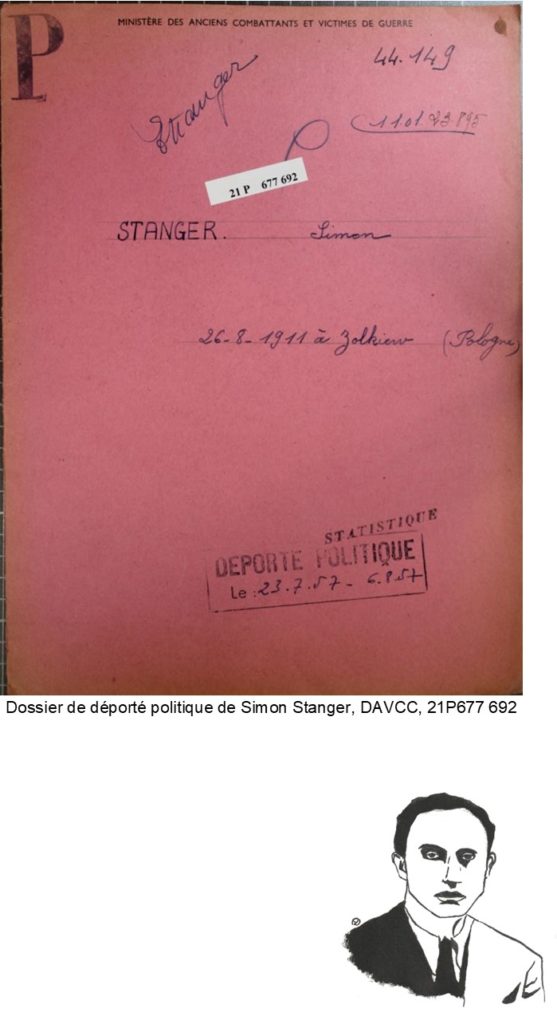

The first records that we found: 1957…?

We first became familiar with the archive material that we already had: Simon Stanger’s application to be officially recognized as having been a “Political deportee“.

The file is dated 1957, twelve years after the end of the war.

What happened to him? Why, when he returned from Auschwitz, was he not immediately recognized as a victim of deportation?

And above all, why the status of “political deportee”? We were puzzled by the fact that Simon, twelve years after returning from the largest concentration camp, had still not been recognized as a Holocaust victim.

We thus began our investigation.

Simon Stanger’s application for the title of Political deportee. Source: DAVCC, 21P677 692

The concept of “Political deportee”

The first archived record

We discovered an official file dating from 1957, held by the French Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War.

The file, which contains 28 pages, gave us our first glimpse into Simon’s life.

On July 23, 1957, the Ministry of Veterans’ Affairs and Victims of War granted Simon Stanger, who was then 46 years old, the title of “Political deportee”. Why? The statutes date back to 1948 (law n°48-1251 of August 6, 1948).

The status of political deportees and internees was established by law n°48-1404 dated September 9, 1948.

The decree of May 11, 1945 gave the following definition: “French citizens transferred by the enemy out of the country, then imprisoned or interned, for any reason other than an infringement of common law, are considered political deportees.”

We therefore realized that the term “political” is not necessarily related to acts of political opposition, but covers much more than that.

We continued our research and discovered that the law of 1948 provided for two types of victims: “Resistance fighters”, who were deemed to be voluntary combatants, and “political” victims, i.e. civilian victims who were covered by the war victims’ compensation scheme. These were defined as people who had been arrested for any reason other than an act of resistance. They therefore include victims of racial persecution, hostages and victims of round-ups, as well as all those arrested on account of their political opinions.

Finally, we discovered that the granting of this title gave the holder the right to a “deportation allowance” worth 5,000 French francs, as well as to the issue of an official political deportee card. In addition, the victim was awarded a medal called the “Médaille de la déportation et de l’internement “, the “Deportation and Internment Medal”.

We were now all set to retrace Simon’s life and to understand why and how he was deported and what he did after his return to France.

A Deportation and Internment Medal

Zolkiew, at the beginning of the 20th century

Simon Stanger was born on August 26, 1911 in Zolkiew, Poland.

In the records, we found several references to his parents.

His father’s name was Jacob Stanger. He was born in 1873 in Belz, Poland. He was a furrier.

His mother’s name was Szewa Stanger, née Lichter, and she was born in 1870 in Zolkiew. She died in 1937.

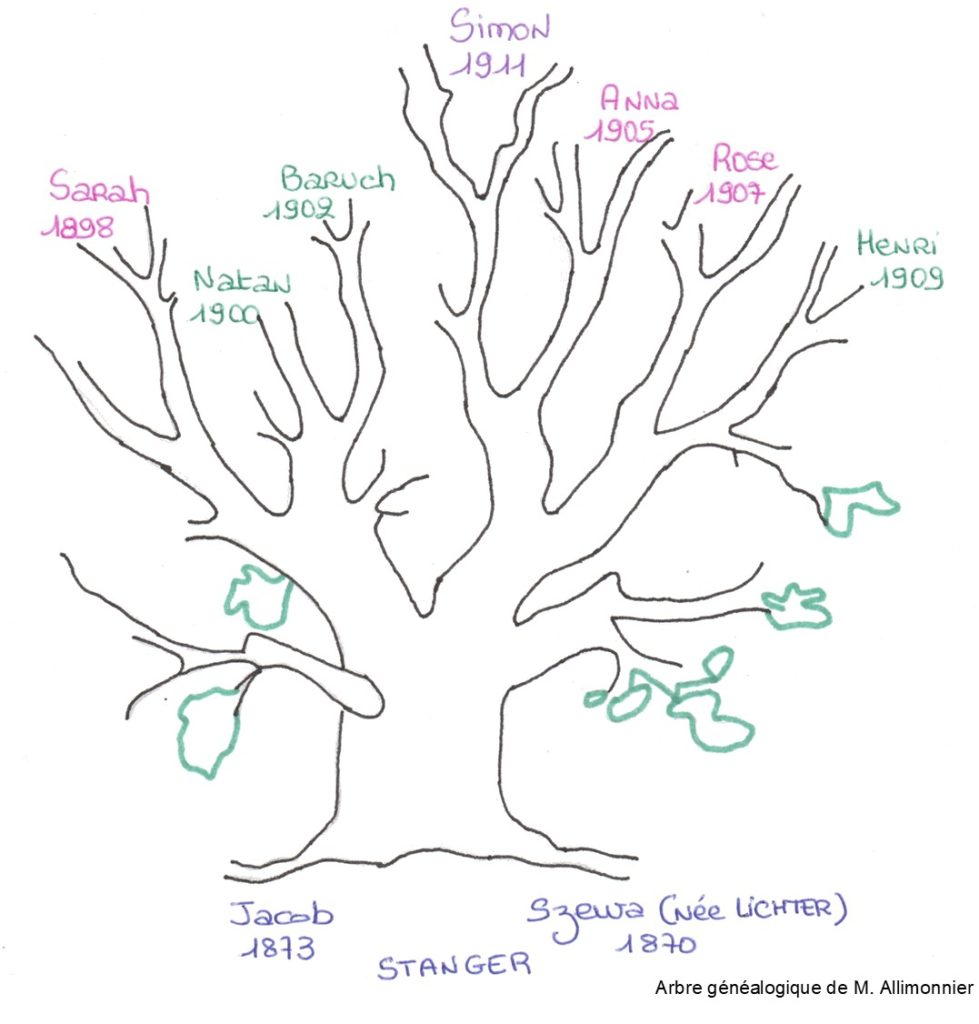

Simon had three brothers and three sisters, all born in Zolkiew.

Judging from the dates of birth, we believe that Simon was the youngest of the seven siblings.

Zolkiew

The town of Zolkiew was founded in 1594 by the voivode, (the equivalent of a prefect, or governor; the head of a voivodship), Stanislaw Zolkiewski.

From 1772 to 1918, the city was ruled by the Habsburg Empire.

From November 1918 to June 1919, the town was part of the People’s Republic of Western Ukraine. In June 1919, after the First World War and the treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which marked the dissolution of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire, it fell under Polish jurisdiction.

Jovkva/Zolkiew is located about 15 miles north of Lviv. It was a town in Galicia with had a population of 6,100 in 1939, where the Hasidic Jews were deeply devout.

On September 18, 1939, the Germans invaded the town, but they left again on September 23, in accordance with the terms of the German-Soviet Pact.

The Red Army arrived in the city on September 24, 1939.

Before the Second World War, the 4,500 Jews made up almost half of the population of the town, but very few survived the Holocaust.

Most were deported to the Lviv ghetto in the southeast of the district, near to which, in 1942, the Belżec killing center went into operation.

The Nazis burned down the old synagogue, leaving only the outer walls.

After the Second World War, the town fell into Russian hands and, in 1951, its name was changed to Nesterov.

It reverted to its original name of Jovska in 1992, when Ukraine became an autonomous republic. This was because in German, it was called Zolkiew.

It is now in Ukraine.

Simon was born in 1911 during the time of the Habsburg Empire. He left for France in 1933. He did not witness the German invasion of Zolkiew, because that only happened in 1939, six years after he left.

R. Alturas

A. Martin

Yad Vashem

On the Yad Vashem website, we find a reference to Yaakov Stanger, who was born in Belz, Poland, in 1904. He was a baker and was murdered during the Shoah. He must have been a member of Jakob’s family.

It is worth noting that most of the Stangers from Belz had their surname spelled Shtanger. Only 7 people from Belz had their names written as Stanger. Simon himself is also listed under the spelling Szimon Sztanger.

Different versions of family names and first names can make the research process more complicated.

Simon had three brothers:

Natan Stanger was born in 1900 in Zolkiew. He was a furrier.

Baruch Stanger was born in 1902 in Zolkiew. He too was a furrier.

Henri Stanger was born in 1909 in Zolkiew. He was also a furrier.

Simon also had three sisters.

Sarah Stanger was born in 1898 in Zolkiew.

Anna Stanger was born in 1905 in Zolkiew. She was a teacher.

Rose Stanger was born in 1907 in Zolkiew.

Simon’s father and his six brothers and sisters were probably all deported. When he returned to France, Simon reported that he had no news of his family since 1939.

The Stanger family tree, drawn by M Allimonier

Paris, 1930

We know from the archives that Simon arrived in France on August 1, 1933, the same year in which Hitler became chancellor of Germany.

Since we cannot find any trace of his parents in the records, we assume that at the age of 22, Simon came to France on his own.

He was a Polish citizen.

Simon settled in Paris, first at 3, rue des Mauvais Garçons in the 4th district of Paris, then at 12, Faubourg Poissonnière in the 10th district.

He soon became a furrier, like his father and brothers before him.

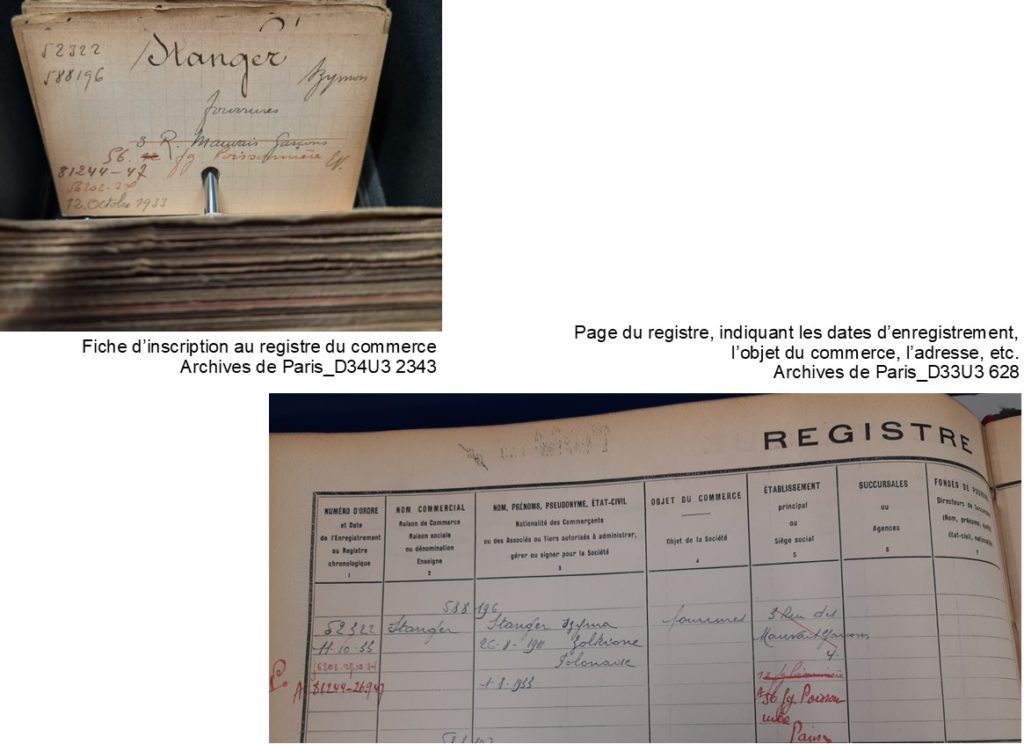

He set up store at 56, Faubourg Poissonnière in the 10th district of Paris. His business was listed in the trade register of the Seine department, under the number 588.196 (Paris archives, reference D34U32343).

Paris in the years 1930-1940

The beginning of the 1930s was a time of growing economic crisis following the stock market crash of 1929, along with increasing extremism, international friction, xenophobia and anti-Semitism, and subsequently the outbreak of the Second World War.

In 1934, the Stavisky affair triggered a French political and economic crisis. The death of the swindler Alexandre Stavisky in mysterious circumstances only served to intensify the already widespread anti-Semitism in France.

In 1935, the Joliot-Curies won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of induced radioactivity.

After the election of the Front Populaire (Popular Front) and a wave of strikes that paralyzed the country, the Matignon agreements were signed between Léon Blum’s government and the CGT and CGPF trade unions. Paid vacations were introduced in France in June 1936.

In 1937, the World’s Fair took place in the Trocadero gardens and on the Champ-de-Mars in Paris.

On September 3, 1939, France declared war on Germany. An armed conflict called the “phony war” ensued. In May 1940, Germany launched a major offensive against France, which caused the population to flee in fear of the German advance. The French army found itself on the verge of defeat in a matter of days.

Then came Pétain’s request for an armistice on June 17, 1940. It was signed on June 22, 1940 in the forest of Compiègne. The French territory was now divided into two areas: the “free zone”, governed by Pétain, and the “occupied zone”, ruled by the Germans.

The German anti-Semitic Propaganda Institute was inaugurated on May 11, 1941, three days before the so-called Green ticket round-up, which took place at the place des Petits-Pères in Paris.

Jews were forced to resign from their jobs, in particular in the civil service. They were also forbidden to enter stores and public places and Jewish-owned assets were confiscated.

R. Bourlet

L. Chatelin

The status of the Jews

On October 3, 1940 and June 2, 1941, the Vichy regime passed two laws on the status of the Jews.

What was the decree of October 1940? It excluded Jews from all positions in the civil service, the professional sector, etc. and introduced the notion of a “Jewish race”. It enabled the implementation of a racist and anti-Semitic policy.

The decree in June 1941 extended this to the whole of France, both the occupied and the free zones.

It was the German order of May 29, 1942 that required Jews in France to wear a yellow star. Information about this was circulated by the police.

The fur trade

When Simon arrived in France in August 1933, he soon began working in a furrier’s store.

Was he an employee at first? Or did he rent the store immediately? We do not know, but, we note that his father and his brothers were also furriers, so he must have already had some knowledge of the fur trade.

Although his home address was on rue Faubourg Poissonnière throughout 1934, he moved house twice during that time.

He moved to 52, rue de Cléry in the 2nd district of Paris and lived there from 1935 to 1936.

After that, he found accommodation at 19, rue des Messageries in the 10th district of Paris, where he stayed from 1939 to 1941. We discovered that there is a now a hotel at this address. Was this also the case in the 1930s, we wonder?

The fur trade

In Paris in the 1920s and 1930s, the fur industry was booming. Workshops and stores were located primarily in the 2nd and 10th districts of the city, in particular in Faubourg Poissonnière, where Simon Stanger set up shop. They were mostly subcontractors to larger firms. A few of the more prestigious furriers were based in the 16th district. Most of them were small businesses that only employed a few people, often from the same family. Some other, bigger workshops employed a larger workforce, often made up of women. The work, which called for great dexterity, was hard and poorly paid. The industry was predominantly made up of immigrant craftsmen, often from Poland. During the German occupation, despite the spoliation of Jewish property, some Jewish businesses were allowed to remain open and keep their workers on in order to make pelisses for the German soldiers.

The fur industry has been in constant decline since the 1960s. Since then, as a result of the relocation to Asia and the campaign against the use of animal skins and furs, the furrier’s trade is becoming a thing of the past.

T. Cadet

J. Mary

s/c de L. Klejman

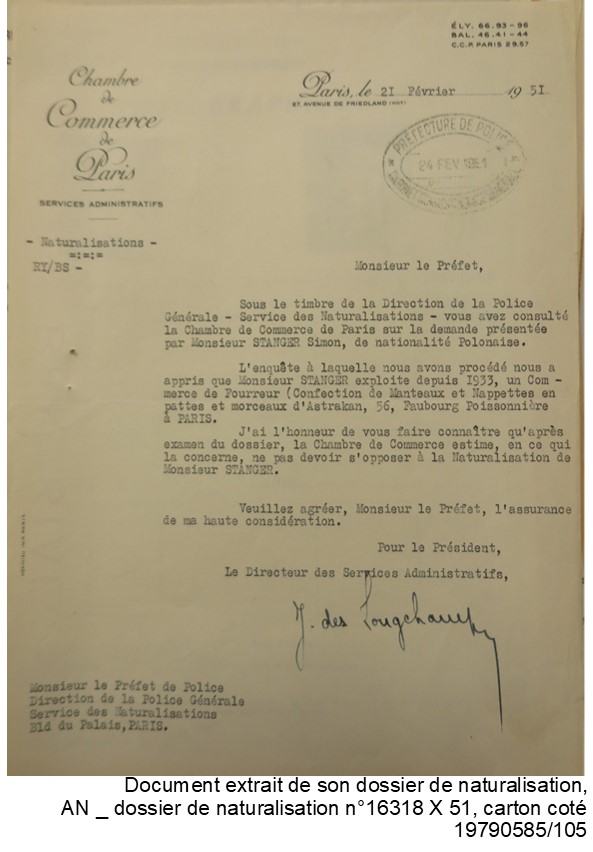

Based in the 10th district of Paris, Simon ran a fur store. His application for French citizenship by naturalization states that he made “coats and rugs/throws out of legs and pieces of Astrakhan fur”.

A document from Simon’s application for French citizenship by naturalization, from the French National Archives, dossier number 16318 X 51

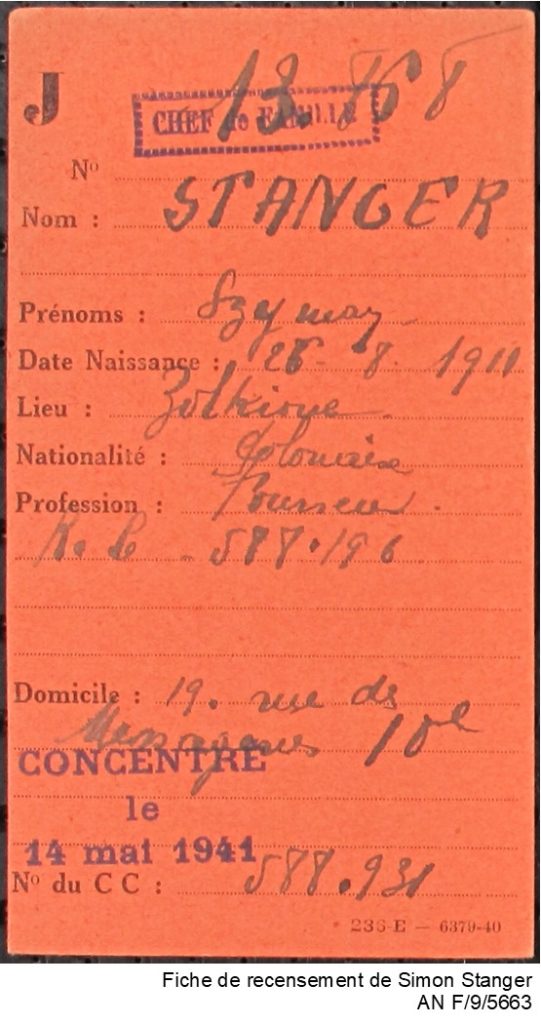

Late 1940, the census of the Jews

Following the German order of September 27, 1940, Jews had to take part in a census. The French police department issued the following notice in the press and on posters:

“Jewish nationals will, therefore, have to report to the police departments of the districts or precincts where they live, bringing with them proof of identity.”

The census took place from October 3 – 19, 1940.

The forms for foreign Jews, such as Simon, were orange, while those for French Jews were blue.

He was listed in the Seine police department’s “adults” file as the “head of the family”. Could this have been a mistake, given that in all the subsequent internment records he was listed as “single”?

Simon Stanger’s census record, from the French National Archives, reference F/9/5663

May 14, 1941, the first arrest

On May 14, 1941, Simon was arrested.

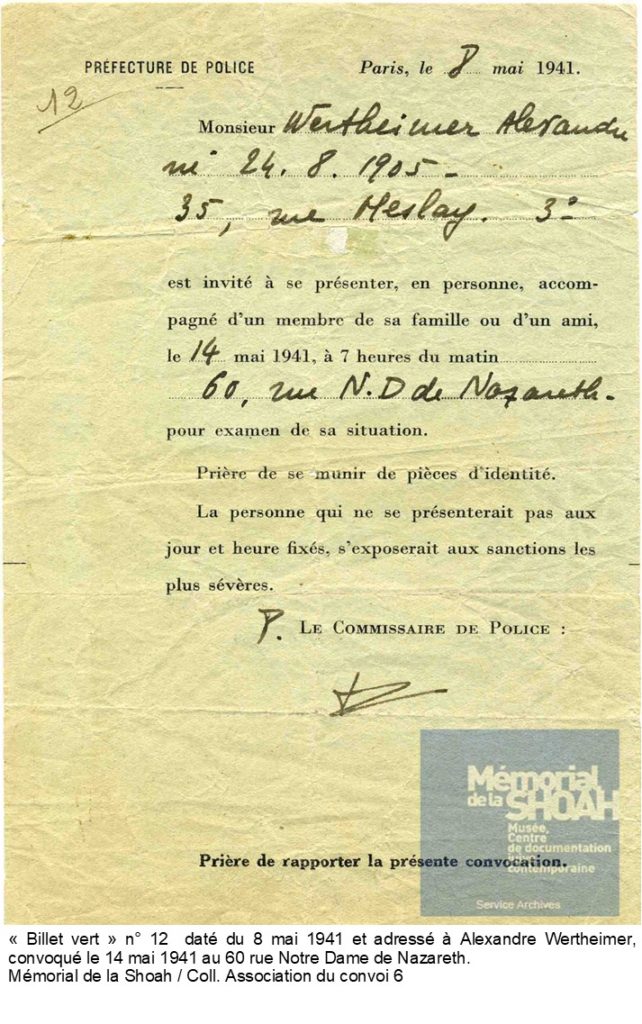

It happened during the first major wave of arrests in France. It is known as the “Green Ticket” round-up”. It only involved Jewish men with foreign citizenship.

The first wave of arrests under the Vichy regime

On Wednesday, May 14, 1941, approximately 5,000 green tickets, signed by the police commissioner, were sent to men between the ages of 18 and 60, living in the Paris area, who were of Polish or Czech nationality or were stateless persons.

This ticket summoned them to present themselves for a “status review” at seven in the morning, at one of the following places, all of which are in Paris: The garage at 52 rue Edouard-Pailleron in the 19th district, the Tourelles barracks on boulevard Mortier, the Napoleon barracks on Place Vandoyer in the 4th district, the rue des Minimes barracks, at 33 rue de la Grange-aux-Belles in the 10th district, at rue Duc, at the Opéra in the 18th district, or the Japy gymnasium in the 10th district.

They had to bring their identity card with them.

They also had to be accompanied by a family member or a friend.

Although it appeared to be a mere formality, it was nevertheless compulsory: “Anyone who fails to appear on the days and at the times set will be liable to the most severe penalties”, the Paris Police headquarters stated on May 10, 1941.

Some of the men realized what was about to happen and fled to the free zone or went abroad, to Latin America via Spain, for example. In doing so, they were saved, but more than half (3,747 out of 6,694) of the people summoned obeyed, including Simon Stanger, because they believed that it was only an administrative formality. Those who did go were immediately arrested, and the person accompanying them was asked to go to fetch their belongings and some food and drink.

They were then put on to buses and transferred to the Austerlitz railroad station.

In David Diamant’s book, Le Billet vert, (the Green ticket) published in 1977, it says: “To avoid contact with the general public, each train flew a yellow flag, a sign of contagious disease (cholera, plague etc.); on the platforms, young SS men, with guns, waited for them and dealt them violent blows with their rifle butts.”

Then they were transferred later the same day. They travelled in third class on four passenger trains to the internment camps in the Loiret department of France. About 1,700 of them were sent to Pithiviers and 2,000 or so went to Beaune-la-Rolande, including Simon Stanger.

Most of them remained there for over a year.

M. Juffroy-Launay

L. Chatelin

Arrests, roundups and the “Jewish file”

During our trip to Pithiviers, the facilitators at CERCIL (the Center for Study and Research on the Internment Camps in the Loiret) explained to us that we cannot really call what happened on May 14 a round-up. In fact, it was a summons for a “status review”, which could well have been perceived as harmless by the people involved.

Naively, in a collaborationist country under German rule, they thought that their status would be legalized, and that they would be granted French nationality. This is also what was so abominable about the collaboration: it succeeded in making people believe that French interests and laws were still in force in the “occupied” zone, despite the German military presence. It was French police officers and gendarmes (military police) who arrested the people who had been summoned, rather than German soldiers, so it did not strike the bystanders as anything particularly unusual.

The Paris region “Jewish file” was compiled with zeal by the Police Department and its eminent leaser, the Prefect of Police, a man called Tullard. The file even surpassed the expectations of the Germans.

The first “real” roundups began in Paris on August 20, 1941, and lasted until the 24th. Then, on December 12, there was the so-called “Notables” roundup (during which 743 lawyers, doctors, shopkeepers, engineers and company directors, whose names were taken from the “Jewish file”, were arrested).

L. Klejman

Who received a card summoning them to attend the meeting?

The list of people who received a green card was compiled from the results of the census carried out from September 1940 by the French authorities, on the orders of the German occupiers, and according to the decree of October 4, 1940, enacted by the Vichy regime, which gave the prefects the power to intern “foreigners of the Jewish race”.

In total, 3 700 Jews were arrested in the Paris area.

In a testimonial from Emile Frajerman, who was arrested on May 14, 1941, at the age of 18, he recounts what he said to his father the day before the round-up: “Papa, I’ve been working since I was 15 years old. What will they do to me? They won’t kill me! They’re going to use us to replace the prisoners of war”. (From the documentary film “La Terre ne ment pas“, “The earth does not lie”, directed by P. Claire, 2009).

In Marie Bekier-Kohen’s testimony about her father, Leiba Bekier, who was arrested on May 14, 1941, she says:

“On May 13, 1941, my father received the summons for the ”green ticket’’ meeting. My mother begged him not to go, but he thought it was just an identity check. He was sent to the camp at Beaune-la-Rolande. We went to see him several times in the camp and were able to walk around the village with him. My mother tried to persuade him to escape with us, but he thought that we would all be in danger if he did not show up back at the camp. He left on Convoy 5 for Auschwitz on June 27, 1942 and we never heard from him again.”

M. Juffroy-Launay

L. Chatelin

“Green ticket” n°12, dated May 12, 1941, which was sent to Alexandre Wertheimer, summoning him to go on May 14 to 60, rue Notre Dame de Nazareth.

Source: Shoah Memorial in Paris and the Convoy 6 non-profit organization.

Simon’s arrival at the Beaune la Rolande camp

On May 14, 1941, the same day on which he was arrested, Simon was taken by train to the Beaune-la-Rolande internment camp. The detainees loaded into third class cars and then the train departed from Austerlitz station.

His registration number was 1747.

The Beaune-la-Rolande camp

Where was the camp?

Beaune-la-Rolande is approximately 60 miles south of Paris, 30 miles northeast of Orléans, 16 miles northwest of Montargis and 12 miles southeast of Pithiviers.

What was the site used for before 1941?

In 1937, the municipality of Beaune-la-Rolande created a sports field and built a gymnasium with showers open to the public.

In 1938, although the local population did not really know why, the seven-acre site was taken over and a number of barracks (modular, portable “Adrian barracks”) were built, which later became the “camp”.

Everyone thought that this camp was intended to accommodate the German prisoners taken at the beginning of the war.

What happened when the camp opened?

At first, the camp was used to house 22,000 French prisoners of war following the defeat of France on Tuesday, June 18, 1940. They were held in appalling conditions.

The German authorities soon extended the camp. Houses and a farm were taken over and the road to Auxy was cut off. The commander was an Austrian officer.

The Germans ran the camp, but there were too many prisoners. They were therefore sent to civilians’ homes, primarily to be fed, but also as servants or to help with other work.

In May 1941, after the so-called “green ticket” round-up, more than 3,000 Jews were arrested, of which 2,000 were interned in the Beaune-la-Rolande camp under the orders of the German authorities.

At the beginning, visits and outings were allowed on the condition that the internees were present at the check-in every day.

The internees were housed in barracks, all piled in on top of each other, on dirty straw, which was never changed, and with no sanitary facilities.

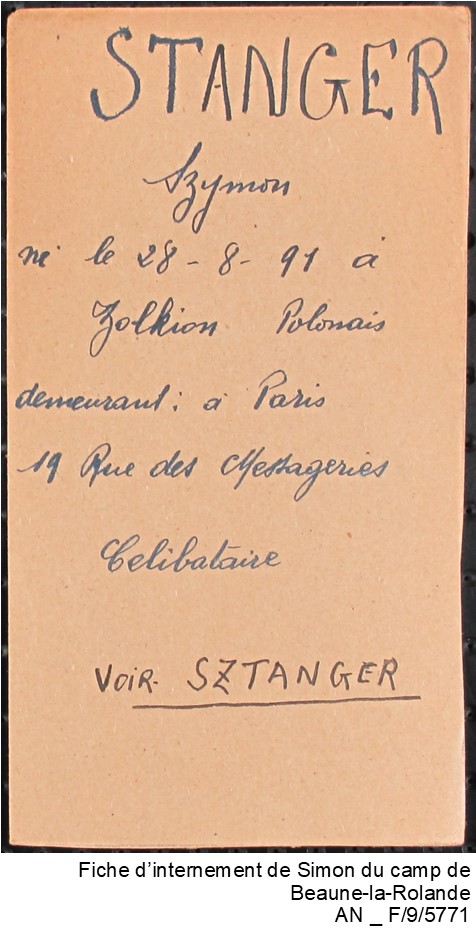

Simon’s internment record card from the Beaune-de-Rolande camp, reference AN_F/9/5771

In the summer of 1942, following the roundup at the Vélodrome d’Hiver, more than 3,000 people were interned in Beaune, in dreadful conditions.

Two convoys left Beaune-la-Rolande for Auschwitz:

June 28, 1942, convoy n°5,

August 5, 1942, convoy n°15.

After July 1943

Aloïs Brunner, the commandant of the Drancy camp, ordered the closure of the Beaune-la-Rolande camp on July 12, 1943.

In 1947, the camp was destroyed. An agricultural school was built on the site.

In October 1964, it was converted into a women’s agricultural college, when the construction work, supervised by the architects Blareau and Guillaume, was completed in 1963-4.

In 1967, the site became a professional agricultural high school.

In 1965, a memorial was erected. The present school is on the “rue des Déportés” (Deportees’ Road).

L. Cailler

G. Lucas

Excerpts from Billet vert, (Green ticket) by D. Diamant, published in 1977:

“The Beaune-la-Rolande camp was made up of twenty barrack huts, each of which could accommodate 120 to 180 people, and sometimes even 200. Some were reserved, partially or entirely, for the camp services (shoe repair, hairdressing “salon”, washrooms, showers, kitchens, infirmary, not to mention a building intended for use as a prison. [This hut was nicknamed the “gnouf”] Later on, one hut was used as a theater and for religious services. The floors of the barracks were made of cement. Only a few of them had floorboards. During the winter, we suffered terribly from the cold; in the summer we were overwhelmed by the heat.”

“At Beaune-la-Rolande, the internees had invented an unusual way to shoe themselves: they cut wooden planks out of old crates, and, with whatever strings or strips of leather they could find, they made “things” to protect their feet.”

A French gendarme (military police officer) keeping watch over the Beaune-de-Rolande camp on May 17, 1941.

Photo credit: Shoah Memorial in Paris

Simon’s first escape, from the Matelotte farm

In late July 1941, there was a call for volunteers to work in the farms in the Sologne, a natural area covering parts of the Loiret, Loir-et-Cher and Cher departments of France.

In light of David Diamant’s book, we wondered about this. Could Simon’s real reason for volunteering have been that he hoped it would be an opportunity to escape? Or, as the author suggests, was he being “punished in some way”?

As shown in the record from the CERCIL archives, Simon arrived at the Ferme de la Matelotte (Matelotte Farm), on July 25, 1941.

The “kommandos” of Sologne

This is what they call the disused farms in the Sologne region (according to a file of that name in the Loiret departmental archives service) to which Jews were sent, supposedly to work.

In fact, in the film “La Terre ne ment pas” (The Earth does not lie), a 2009 documentary written and directed by Philippe Claire, Emile Farjerman says “Draining the marshes was just a sham. It was simply to put the Jews to work.”

These kommandos were therefore a pure lie. In reality, the Jews did not work. The French gendarmes did not know what to do with them. They had no tools or equipment.

The “kommandos of Sologne”, explains Benoît Verny, the historian responsible for research at CERCIL, “was a plan by the prefecture that brought together the lack of manpower, the fact that the Jews had to be put to work, and the fact that since the land did not lie, they had to do something with the land.”

The prefect of the Loiret department therefore chose some abandoned farms in the Sologne area to provide work for the Jews. They were a type of annex camp to those of Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande.

A total of 386 internees, men from all walks of life, were sent to Sologne. They were divided up between three farms:

1/ the Matelotte farm, located between Cerdon in the Loiret and Argent-sur-Sauldre in the Cher department,

2/ the Rosoir farm, near to Vannes sur Cosson,

3/ the Ousson farm.

Some people living near these farms welcomed the internees, sometimes doing them a favor by sending their mail, hosting their families and helping them to escape.

In their memory, the CERCIL Memorial Museum for the children of the Vel d’Hiv roundup has designed a memorial trail that includes the farms.

This gave us a better understanding of the day-to-day life of the Jewish men who were held in these farms before they were deported. We also followed in the footsteps of the people who succeeded in helping them to escape.

On the subject of the escapes, we come back to the testimony of Emile Frajerman, who was also sent to the kommandos of Sologne, at the age of 18.

Here is what he said: “There were moments of complacency. They knew very well that we couldn’t escape, that the railroad stations were too far away.” (From the documentary film “La Terre ne ment pas”, directed by P. Claire, 2009). We know that Emile himself also managed to escape on July 1, 1942.

L. Bénardeau

M. Thiret

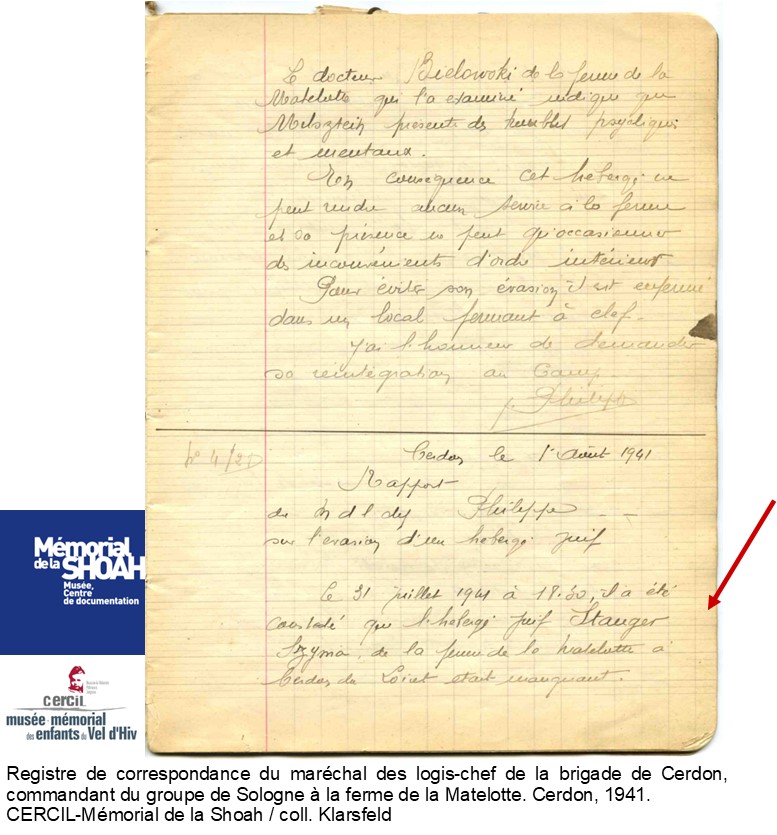

In the register that was kept at the Matelotte farm, the Chief Field Marshal of the Cerdon brigade, Philippe, wrote a report on August 1, 1944, about the escape of a “Jewish resident“.

It says:

“On July 31, 1944, at 6:30 p.m., the Jewish resident Stanger Szymon, from the Matelotte farm, in Cerdon du Loiret, was found to be missing. He was present at the 1:30 p.m. check and then presumably took advantage of the comings and goings in the courtyard of the barracks, caused by the bad weather, to get away from the camp.

Searches were fruitless and his escape was reported by telephone to the gendarmerie.”

Work outside the camps: Sologne

“The history of Sologne is a chapter apart. “Responsible for the war”, the Jews, “these parasites who did not know what work was”, were to be assigned to the toughest tasks. General Huntzinger, the prefect of Orléans and the commanding officers of the camps of Pithiviers and Beaune-la-Rolande shared family ties. According to the Orléans press, they received a sum of 300 million to organize the reclamation of the Sologne marshes. […] When the request for volunteers was made [at Beaune-la-Rolande], the clandestine organization and the barrack leaders, by mutual agreement, initially refused. Discussions took place. Nevertheless, it was decided not to resist in the event of a transfer. This decision was taken in the hope of finding better opportunities for escape in Sologne. […] In the end, the commandant sent to Sologne the internees who had been punished in some way. 275 internees went, divided into three groups of 90 men each. They were sent to three abandoned farms. Contrary to expectations, there was more freedom and the work was bearable.”

explains D. Diamant in his book, Le Billet vert.

The entry made in the register by the commandant of the Sologne group at Matelotte farm

Simon headed for Lyon

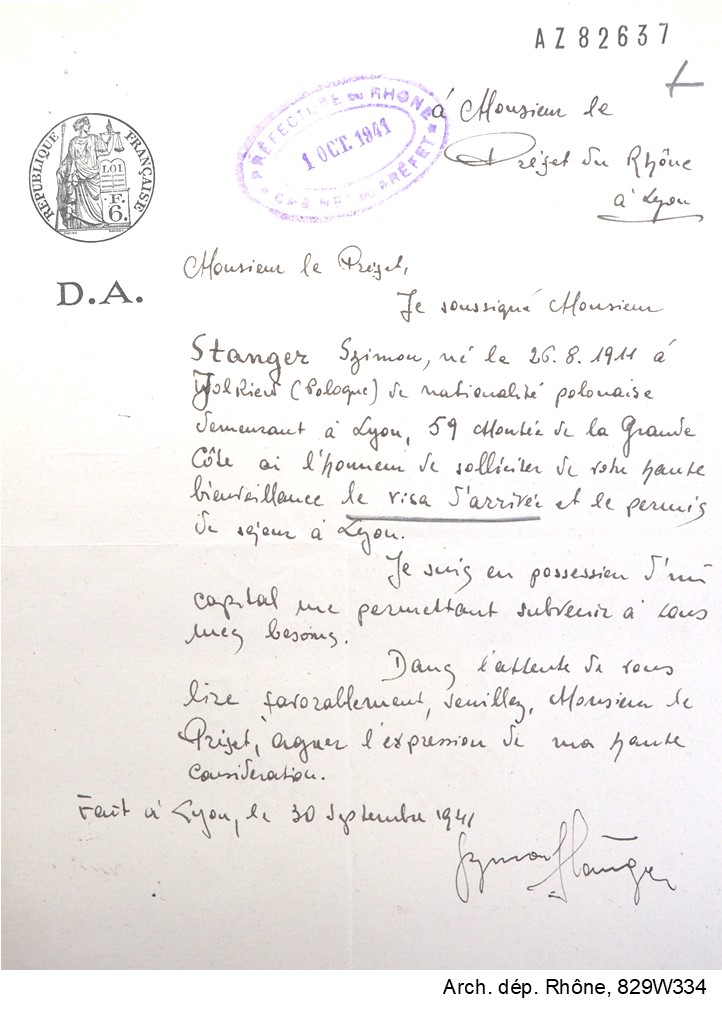

Simon escaped from Sologne on July 31, 1941. We found the next trace of him in Lyon, thanks to a letter written in his handwriting and signed “Szymon” on September 30, 1941.

He had thus succeeded in crossing into the free zone after he left the Matelotte farm. But how? Who with? We have been unable to find out anything about this.

Nevertheless, on reading his letter, we noticed an important detail: “I am in possession of enough capital to meet my needs”. In September 1941, after having been arrested and having escaped from the camp, he still had some money. He must have covered his back and had help from someone to get some money back, given that Jewish property had been confiscated, or “Aryanized”, in the occupied zone since the autumn of 1940, and since July 1941 in the “free” zone! This might explain why he was able to escape.

We found out later, again in a file from the Rhone departmental archives, reference N° 829W334, that he had 14,000 francs on him.

Lyon, 1941

When Simon Stanger arrived in the city of Lyon, he stated in his letter to the prefect that he was a Polish citizen, which was factually true, although Poland was by then ruled by Germany. He was therefore unable to have his identity card renewed.

Since September 24, 1940, Alexandre Angeli had been the prefect of Lyon. At the end of the war, he was judged and sentenced for collaboration. He had very wide-ranging powers and was actively involved in enforcing the laws of the Vichy regime.

We were amazed to see that Simon, although he had escaped from detention and was surely a wanted man, still wrote to the French authorities, who had been responsible for arresting him in the first place.

Simon’s letter to the prefect of Lyon, from the Rhone departmental archives, ref. 829W334

We also noticed that Simon’s handwriting and signature suggest that he was very well-educated and had a perfect command of the French language. Did he write the letter himself? Did he copy it? Or might it have been written and signed for him by a French person? It is the same in his application for French citizenship by naturalization. He wrote very good French.

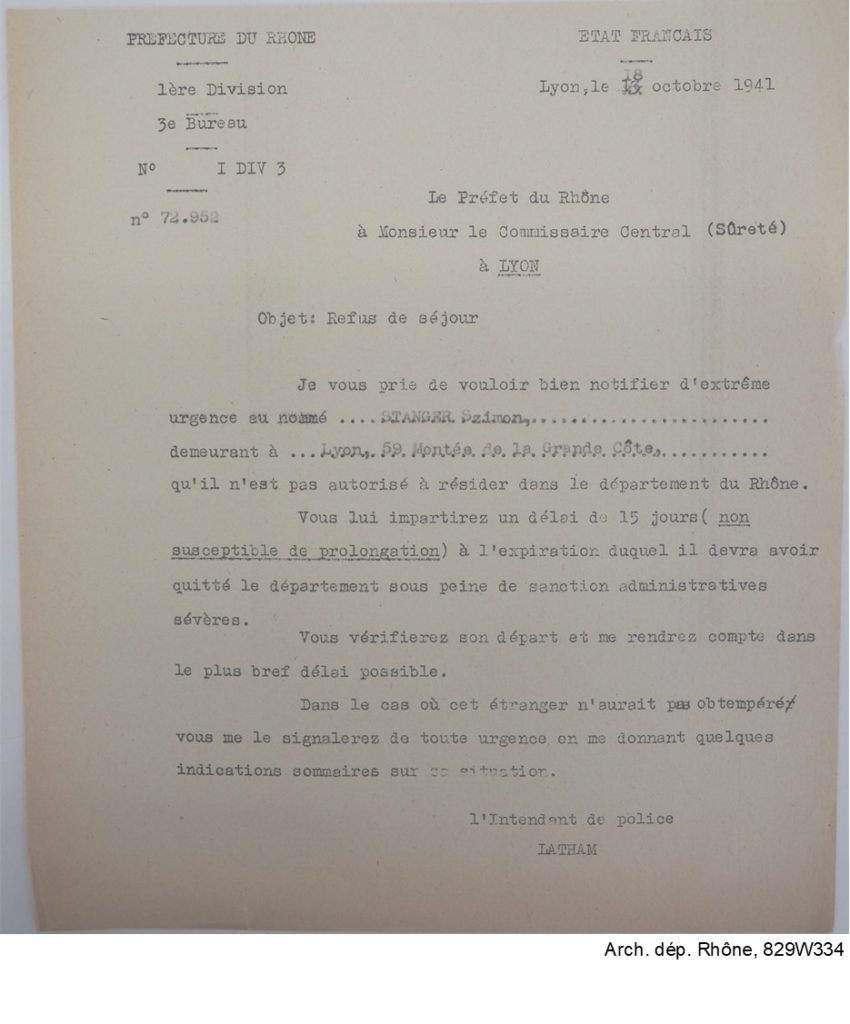

In response to Simon’s letter, the Prefect of the Rhone wrote to the Commissioner of Security in Lyon, saying “he is not authorized to reside in the Rhône department” and asking him to notify Simon Stanger that he had “a period of 15 days to leave the department, under penalty of severe official sanctions.”

Letter dated October 18, 1941, from the Prefect of the Rhône to the Central Commissioner of Security in Lyon.

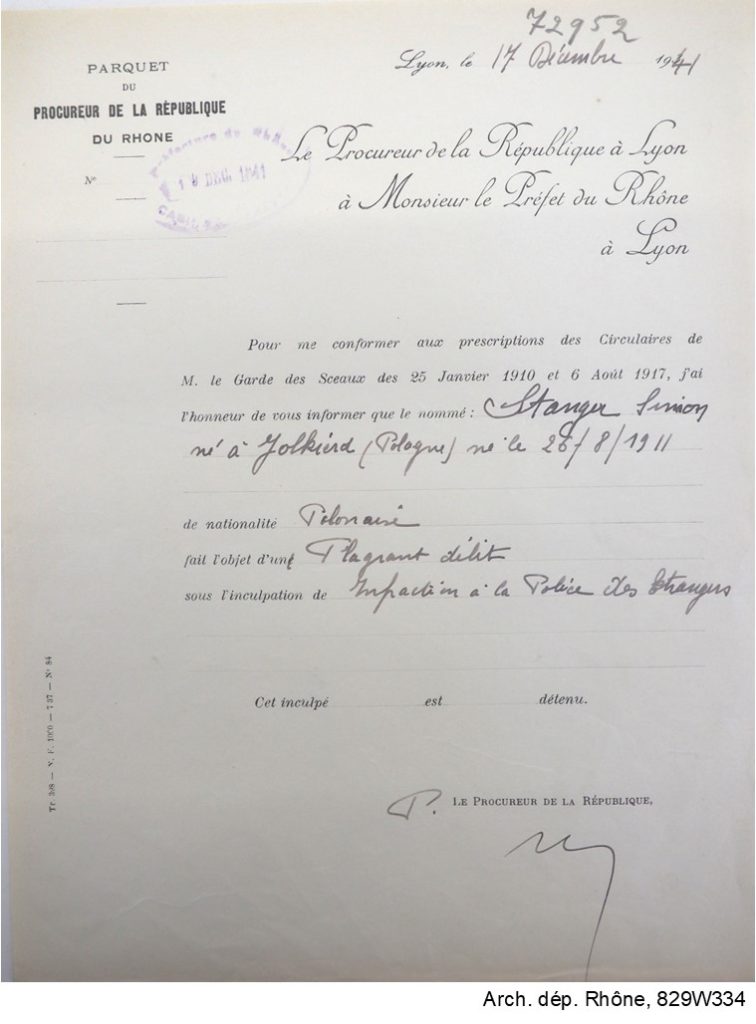

Lyon, 1941, the second arrest

In spite of the letter from the Rhône prefecture, dated October 18, 1941, giving Simon Stanger, living at 59 Montée de la Grande Côte in Lyon,15 days to leave the city, Simon decided to stay on and go into hiding.

He was arrested again in December 1941 at a hotel at 66, rue Mercière, in which he was staying at the time.

In a letter addressed to the Prefect of the Rhone (Rhone departmental archives, file n° 829W334), on December 17, 1941, the reason for the arrest was describe as follows: “Flagrant offence on the charge of an infraction against the Foreigners service of the Police.”

Lyon, with no identity papers

Simon was arrested for the second time, this time in the free zone. He obviously chose to stay on in Lyon rather than follow the order given to him to leave the Rhône department “under penalty of severe official sanctions”.

He was arrested because his identity papers were valid, according to the law of May 2, 1938. He was unable to produce the necessary documents when stopped by the Foreigners service of the Police.

For failure to produce the required documents, an identity card and a residence permit, Simon was incarcerated in the Saint Paul Prison in Lyon.

He was detained there from December 16, 1941 to January 9, 1942.

The file in the Rhone departmental archives includes an extract from the custody register of the Lyon prison (reference 829_W_334).

We discovered that was single and was 5’7” tall.

An individual data sheet was drawn up. It mentions that he had a “wide face” and includes his 10 fingerprints.

He was released from custody following a court ruling on January 9, 1942. (Rhone departmental archives dossier, ref. UCOR 1417).

The Saint-Paul prison

The Saint-Paul and Saint-Joseph prisons in Lyon were both detention centers for men.

They are located in the second district, south of the Perrache train station in the Confluent area, on the banks of the river Rhône.

The Saint-Paul prison was built between 1860 and 1865 by Antonin Louvier. At the time, it was regarded as a most modern and most suitable detention facility.

Antonin Louvier designed this innovative prison, which had six buildings around a surveillance rotunda with a chapel above it. It was constructed entirely of cut stone.

The overcrowding of the prisons made the life of the inmates unbearable. The poor sanitary conditions, the everyday violence and the dilapidated state of the premises led to the closure of the two prisons in 2009.

The Saint-Paul prison has since been renovated and now houses a university campus.

S. Fernandes

R. Rizzo

Klaus Barbie, the “butcher of Lyon”

In 1987, the German Nazi war criminal, Klaus Barbie, was imprisoned for life in the Saint-Joseph prison. He died there on September 25, 1991.

During the Second World War, from 1942 onwards, Nikolaus, known as Klaus, Barbie was the head of the Gestapo in Lyon.

He was single-handedly responsible for the execution or murder of more than 4,000 individuals and the deportation of 7,500 Jews.

His brutality earned him the nickname “the Butcher of Lyon”.

Among the many crimes that Klaus Barbie committed was the deportation of a group of children from a home in Izieu, in the Ain department of France. 44 children, aged 4 to 17, and 7 supervisors were arrested. The fact that the children were Jewish had been a closely guarded secret. They were transferred to Drancy and then most of them were deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered as soon as they arrived.

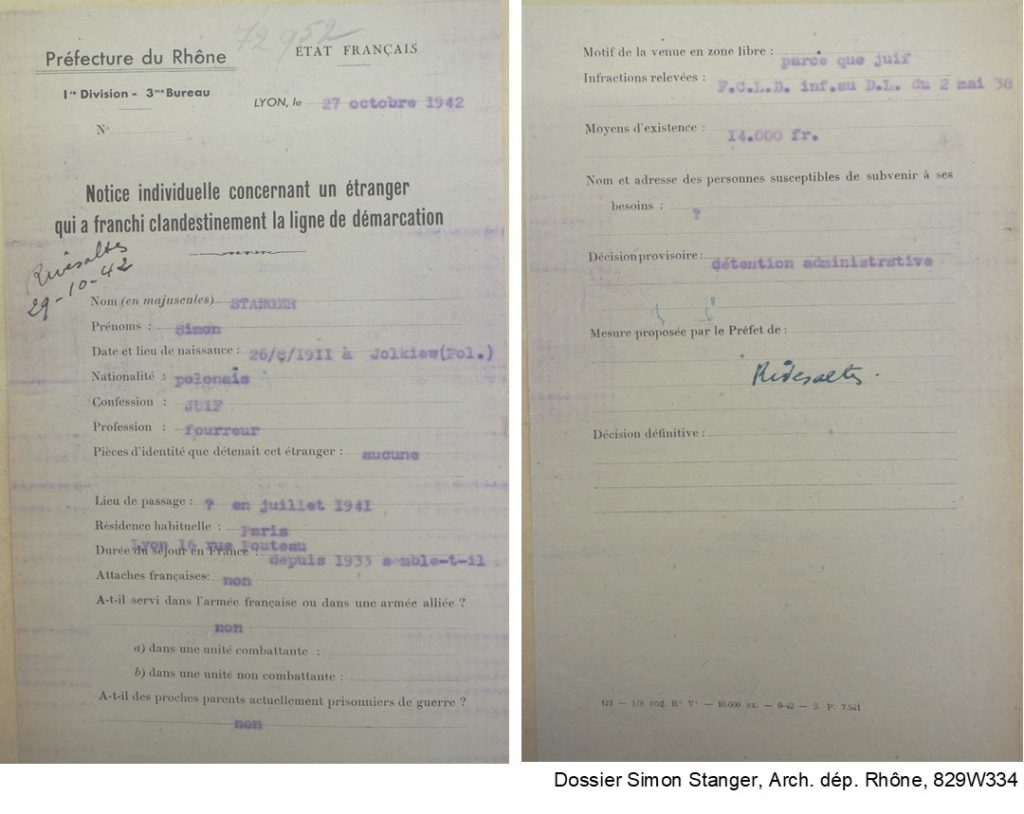

Lyon, late 1942, the third arrest

When Simon appeared before the Court for not having been able to produce his identity papers, he was acquitted on the basis of a letter that the Prefect of the Rhône wrote on January 8, 1942 to the Procureur de la République, the State Prosecutor (Rhône departmental archives, file n°, 829_W_334).

In this letter, it is stated that the foreigner Simon Stanger seemed to be able to provide a legitimate explanation, having submitted “in good time, an application for permission to reside in the Rhône.”

Simon was released on January 10, 1942.

We found the case file with a record of the court judgement (Rhône departmental archives: Ucor 1417) thanks to the historian V. Sansico, who wrote a book in 2015 called La Justice déshonorée, 1940-1944 (Disgraced Justice, 1940-1944) and who discusses the Simon Stanger case. We would like to thank her for this.

From then on, Simon lived his life in hiding.

He was found again while staying with Mrs. Angèle Eme, at 16 rue Pouteau, in the 1st district of Lyon.

At the end of October 1942, Simon was the victim of a round-up and was arrested again.

An “individual notice concerning a foreigner who crossed the demarcation line in secret”, from the Rhône prefecture, tells us that he had most likely crossed the line in July 1941 (?), that he had 14,000 francs in his possession, that he had already committed an offence when stopped by the Police service for Foreigners and lastly that he was to be remanded in custody at Rivesaltes (Rhône departmental archives, file 829_W_334).

October 1942, the Rivesaltes camp

On October 27, 1942, according to a decision by the Rhône prefecture, Simon was sent to the Rivesaltes camp, near Perpignan, in the Pyrénées-Orientales department of France.

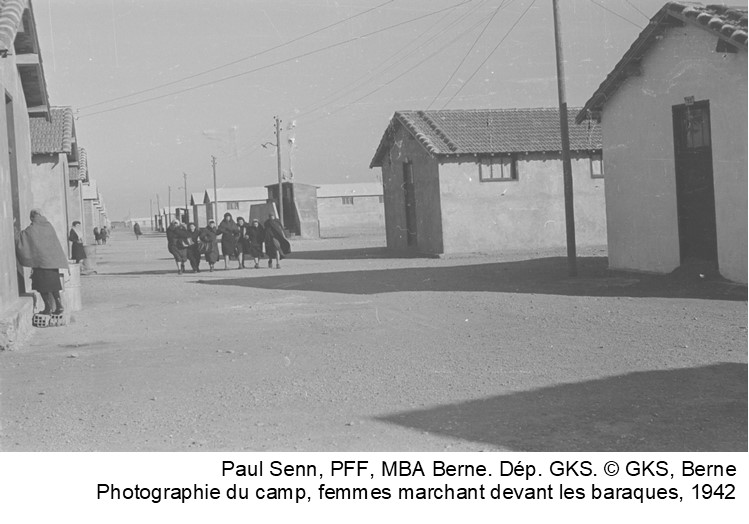

Rivesaltes before the war

The Joffre camp, known as “Rivesaltes”, was founded in 1938, ten miles from Perpignan, to the east of the Pyrenees. It officially opened in February 1939 as a military facility. It covered around 1500 acres.

1939 saw the end of the Spanish Civil War. The fall of Barcelona led to the arrival of thousands of Spanish refugees in France. The French authorities were in a state of panic and were overwhelmed.

After the establishment of the Vichy government, the structure of the internment system changed.

Rivesaltes during the war

The camp was used initially as a refuge for Spaniards fleeing their homeland. It was an accommodation center for families. Later on, it was used for the internment of gypsies and Jews.

On May 31, 1941, the camp had 6,475 inmates of 16 different nationalities (53% were Spanish, 40% were foreign Jews, 7% were French gypsies).

In 1942, the camp was used to gather all the Jews arrested in the free zone. It thus became the “Drancy of the free zone”. Several deportation convoys departed from Riversaltes, first stopping at Drancy.

At the end of November 1942, the German army moved into the Rivesaltes camp. They returned it to its original purpose as a military camp until August 19, 1944, when they left.

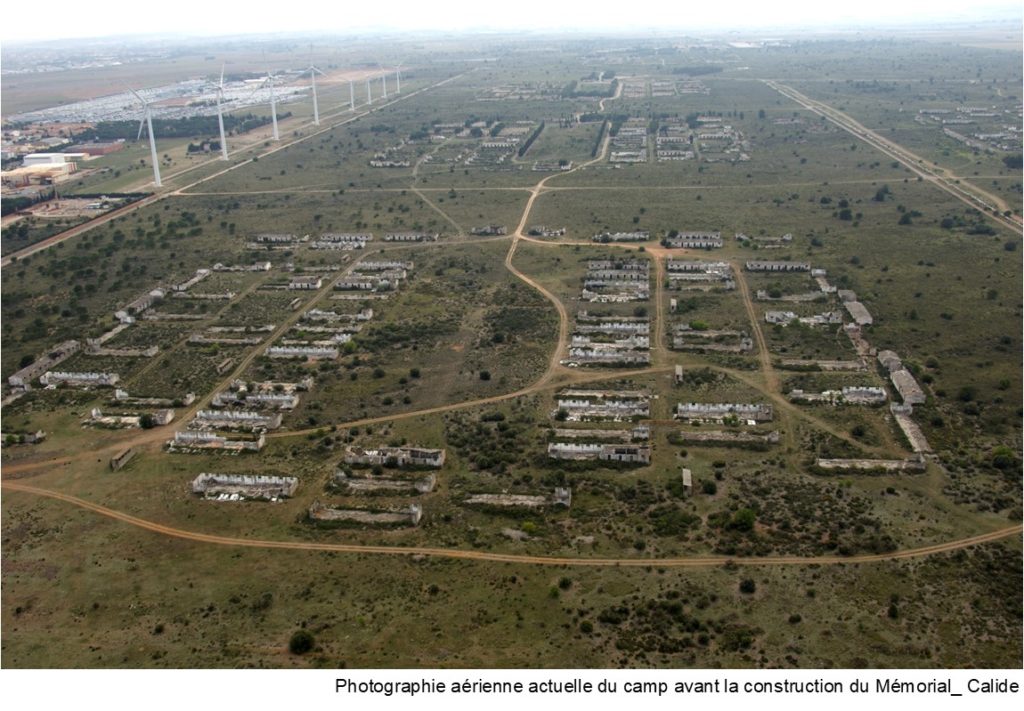

Rivesaltes after the war

A few weeks after the Germans left, the camp became a supervised residential center, that is, an official detention center or prisoner of war camp.

Between 1945 and 1946, thousands of people (Austrian, German and Italian prisoners of war, etc.) passed through Rivesaltes.

In 1948, the Joffre camp once again became a military base.

However, it was again used as a transit camp during the Algerian war in the early 1960s, in particular for the Harkis.

The Rivesaltes camp was the largest internment camp in Western Europe, having spanned a civil war, a world war and a colonial war.

Today, the Rivesaltes camp is a memorial site. It spans the municipalities of Rivesaltes and Salses-le-Château. It pays tribute to all of the people who were incarcerated or accommodated in the camp.

C. Beyhier-Sarron

T. Prévost

L. Colodeau

H. Larissi

C. Allimonnier

A. Gentet

Woman walking beside the barrack huts at Rivesaltes camp in 1942

Late 1942, Simon’s second escape

Simon was transferred to the Rivesaltes camp on October 29, 1942.

He did not stay there for long, however. We discovered that he escaped in November 1942, on the 15th to be exact.

We also know, thanks to file in the Rhône departmental archives (file 829_W_334), that he returned to Lyon, once again to the home of the same landlady, Mrs. Angèle Eme, at 16 rue Pouteau, in the 1st district of Lyon.

In a letter dated March 19, 1951, written with regard to his application for French citizenship, it is mentioned that: “The man named Stanger Simon, born on 26/8/1911 in Zolkiew (Poland), to Jacob and Stewa Sichter, of Polish nationality and Jewish faith, is said to have lived clandestinely from the end of 1941 to 1944 at the home of Mrs. Eme Angèle, 16 rue Pouteau in Lyon (1st district)”.

We are curious as to why Simon went back to Lyon, when he had already been arrested there twice.

Photo of the Rivesaltes camp before it was turned into a memorial site

June 1944 – the fourth arrest, in Lyon

Back in Lyon, while staying with the same landlady, Simon was arrested a fourth time, on the evening of June 24 or 26, 1944.

A document in Simon’s file to be recognized as a political deportee reads as follows (DAVCC, cote 21P 677 692):

“Mrs. Eme […] declares that she secretly sheltered Simon Stanger from the end of 1941 to 24 or 26/6/1944. She is only aware of the arrest, following which he was interned in Rivesaltes. She heard from some people, she does not remember who, that her tenant had been arrested by the Militia on the evening of the 24th or 26th during a raid in the Croix Rousse district. The next day, she was visited by a man claiming to be from the Gestapo, who took delivery of everything that belonged to Stanger. […] She had no further news of him until 1945, after his liberation.”

The French Militia

On January 30, 1943, the Vichy regime set up an armed group called the French Militia.

The official leader of the group was Pierre Laval, head of the Vichy government, but the Militia was led by Joseph Darnand.

There were several conditions for becoming a member: to be French by birth, not be Jewish, not belong to any organization, be volunteers and be approved by the chief of the department.

Collaborating with the Nazis, the Militia was involved in tracking down Jews, Resistance fighters, partisans, STO draft dodgers and anyone else the regime deemed dangerous. Its vocation was to be “the main instrument for the moral, intellectual and social recovery of the country.” (Extract from the speech given by M. Caillard, departmental head of the French Militia, in Carcassonne, on February 28, 1943).

It had more than 30,000 members.

The Lyon Militia

It was 1943. There was no longer any distinction between the occupied and non-occupied zones. In the south, the Militia was based in Lyon. It had a thousand members, divided into five units.

600 of them made up the ranks of the Franc-Garde, formed in June 1943, which essentially fought against Resistance groups. It had a reputation for using excessive violence. Its members could be recognized by their clothing: black uniforms and berets marked with the Greek gamma.

Another section of the group was led by Joseph Lécussan and Paul Touvier. This was the documentation-intelligence service: they looked for any information on real or suspected adversaries.

During the last six months of the Vichy regime, the Militia relentlessly recruited new members and claimed many lives: they were responsible for the assassinations including those of Jean Zay on June 20, 1944, 7 Jewish hostages in Rillieux-la-Pape on June 29, 1944 and Georges Mandel on July 7, 1944.

In Lyon, the Militia set up its headquarters in the heart of the city, at 85, rue de la République, just a mile or so from where Simon was staying.

M. Grejon

E. Jahier

Paul Touvier, the head of the Militia in Lyon

Paul Touvier, who worked for the SNCF (French Railways), joined the Militia in 1943. He became head of intelligence in Savoie, in the Rhône, and then at a regional level.

He fled in 1944, sentenced to death in absentia in the Rhône in 1946, then in Savoie in 1947.

His remained in hiding until 1971, when he was pardoned by Georges Pompidou.

The publicity surrounding this decision in 1972 caused an outcry and sent him back on the run.

He was finally arrested in 1989, two years after the trial of Klaus Barbie.

In 1994, he was convicted of complicity in crimes against humanity. He died in Fresnes prison on July 17, 1996.

The Montluc prison

Arrested on June 26, 1944, due to his own carelessness (?), Simon was interned in the Montluc prison.

He was held there from June 26, 1944 until July 3, 1944, when he was transferred to Drancy.

The Montluc prison is located at 4, rue Jeanne-Hachette in the 3rd district of Lyon. It was built in 1921 on the slopes of Fort Montluc.

Built on land belonging to Fort Montluc and the Ministry of War, the prison took its name from the Fort, but the buildings were completely separate.

In 1921, following the inauguration of the Franco-Chinese Institute in Lyon, at Fort St-Irénée, a hundred Chinese student workers who had been refused admission decided to occupy the Fort. They were then removed by the police and taken to “Fort Montluc”.

In 1926, the Montluc prison was made available for use by the civil justice system, but was little used due to a decrease in the civilian prison population in the 1920s and 1930s, and the prison was closed in October 1932.

In December 1939, the prison was put back into service. The usual suspects of the military justice system were held there, as well as a number of communist militants.

After the signing of the armistice on June 22, 1940, France was divided into two. The city of Lyon was in the free zone.

The number of people interned in Montluc increased. In 1942, about 400 people were interned in this prison, which was designed for 127 people.

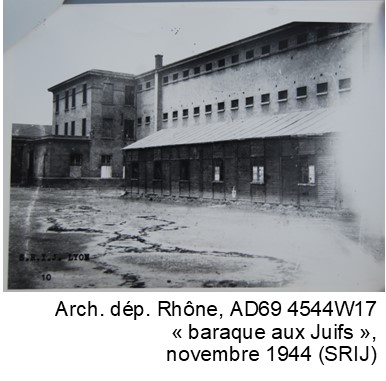

The prison was requisitioned by the German authorities. 7731 people were imprisoned there between 1943 and 1944, including Simon. Thousands of men and women, hostages and Resistance fighters were persecuted there. All areas of the prison were used to lock up victims awaiting transfer or deportation: they were held not only in the 43 square foot cells, but also in the workshop, the store, the refectory and a barrack hut in the courtyard (which was demolished after the Second World War), known as the “baraque aux Juifs”, the “Jewish hut”.

Between 1943 and 1944, up to 1,300 people were imprisoned at the same time, even though the prison had room for only a hundred.

P. Renoncé

R. Da Silva Oliveira

The French academic, André Frossard, testified on May 25, 1987, during the Barbie trial. He recounted the detention conditions in the “Jewish hut” at Fort Montluc. He states:

“We lived there as if we were condemned to death; it was the Jewish hut that supplied the hostages; we were awaiting execution. […] To be a Jew in Montluc meant to endure a harsher regime than anyone else. They were not even treated as enemies or as an inferior race, but as an inferior species.”

(http://alainjakubowicz.fr/index.php/2017/05/25/25-mai-1987-retour-baraque-aux-juifs/)

Interior view of Montluc prison, taken in November 1944.

From the Rhône departmental archives, ref. AD69 4544W17

The “baraque aux Juifs”, or Jewish hut, in November 1944.

From the Rhône departmental archives, ref. AD69 4544W17

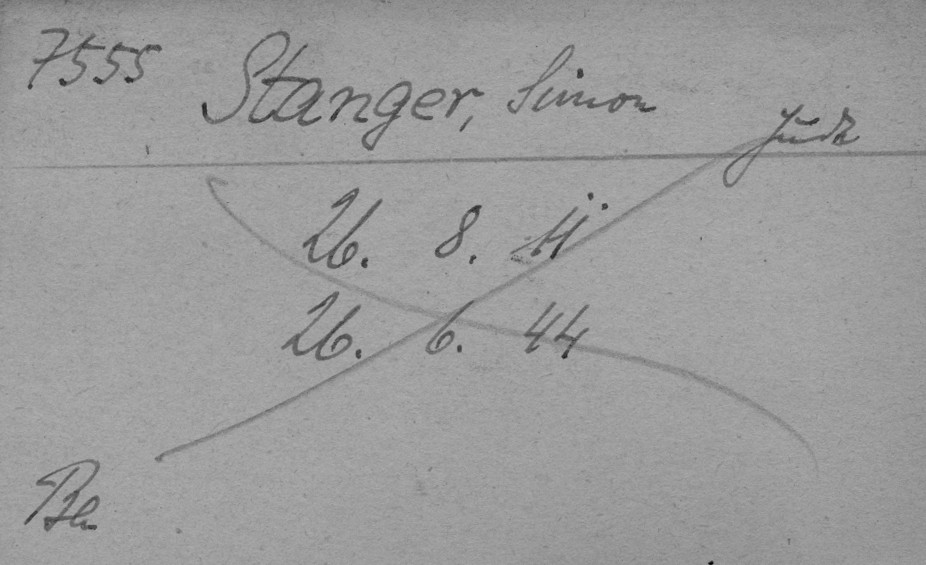

Scan of the German record card for Simon Stanger. From the Rhône departmental archives, ref. 3335W21.

The German record card for Simon Stanger shows his name, the date that he arrived in Montluc and his date of birth. On the top left is his prisoner number: he was the 7555th prisoner of the German political police to be registered at Montluc. On the bottom left is the place where he was interned (Ba = Barrack) and the inscription “Jew” in German is on the right, under his name.

Simon Stanger in Drancy

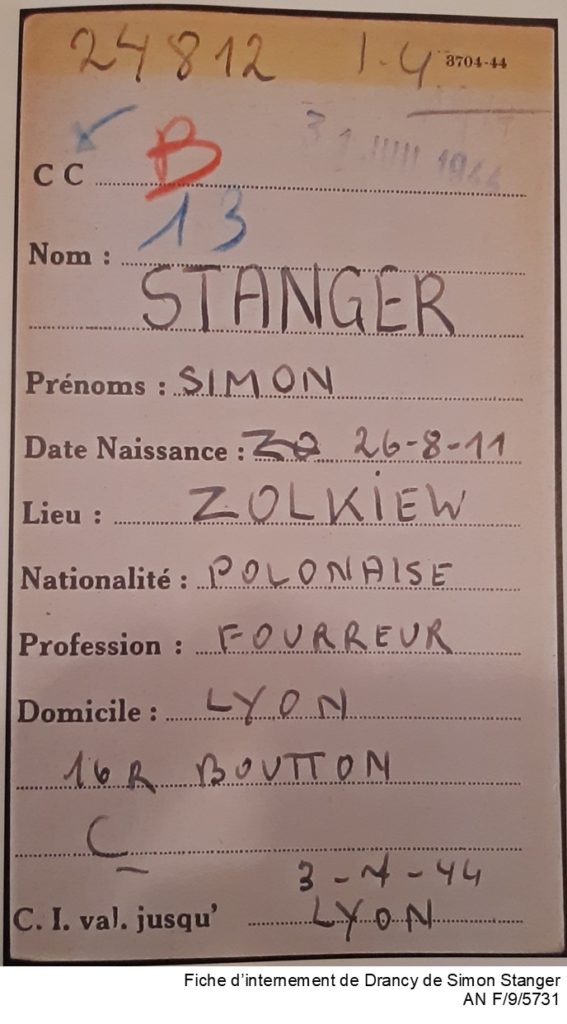

As noted on his Drancy camp internment record, Simon arrived there on July 3, 1944.

He spent 28 days there.

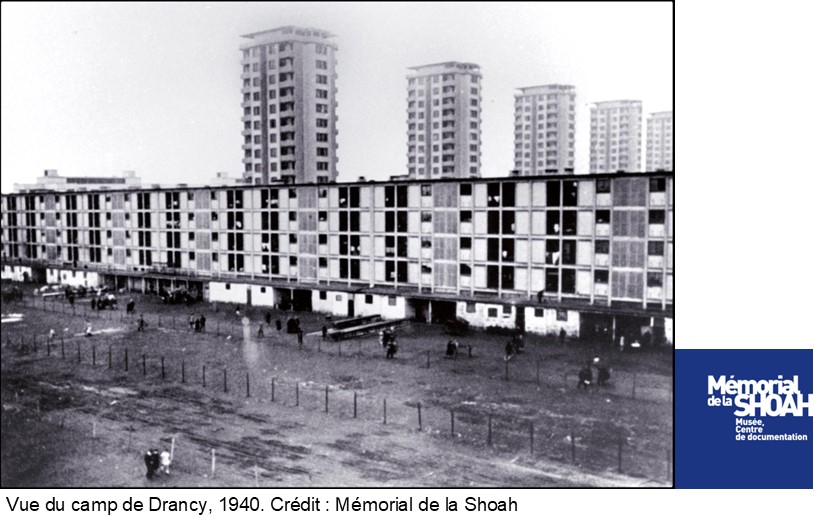

Drancy, or “la cité de la Muette”

Drancy camp was in Seine-Saint-Denis, a suburb of Paris in the Île-de-France region of France.

In the 1930s, some low budget apartments were built for families from Drancy. It was very modern and bold project at the time! The housing complex was built between 1931 and 1937.

The architecture of these buildings was very distinctive, since standard, prefabricated materials were used throughout. The site was intended to provide 1,250 housing units. There were a series of 14-storey towers, each with two long 2-3 story buildings adjoining it. The buildings were nicknamed “the comb”, and were built in the shape of a horseshoe around a space called the “entrance courtyard”.

Then, in the 1940s, the unfinished building complex was used as an internment camp.

The French internment camps were official detention centers or refugee or prisoner of war camps, and then assembly camps for Jews.

In August 1941, Drancy became an assembly and transit camp.

From August 20, 1941 to August 17, 1944, nearly 80,000 people (men, women, children) were interned in the Paris suburb, simply because they were Jews.

On September 20, 1941, the Red Cross was given permission to set up an office in the camp. They provided meals to the camp, which were delivered by a Jewish Solidarity Committee “de la rue Amelot“.

After that, new furniture for the dormitories was delivered: bunk beds, straw mattresses and, blankets. The internees were allowed to receive letters every two weeks.

About 30 people died in the camp between October and November 1941. During this time, 750 interned patients were released under the supervision of a commission including a doctor from the prefecture and some German servicemen. In December 1941, some very sick people were transferred to various hospitals.

On July 3, 1942, at around 6 a.m., the French police picked up all the patients and took them back to Drancy. The gendarmes who were in charge of searching the patients often took advantage of the opportunity to confiscate a little of what they wanted for their own use or to sell on the black market. Visitors were not allowed.

The three forced labor camps in Paris

There were three satellite camps attached to Drancy. They were in Paris itself, and were used for forced labor (Dienststelle Westen): Lévitan, at 85-87 rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin, in the 8th district; Austerlitz, at 43 quai de la Gare, also in the 8th district; and one at 2, rue de Bassano, the former mansion of the Jewish family Cahen d’Anvers, where they made haute couture fashion garments and luxury furs. L. Klejman’s grandmother spent the last few months of her life there before she was deported.

Up until July 1943, 63 convoys departed from Bourget-Drancy railroad station. After that, they left from Bobigny. In total, more than 65,000 people were sent to the killing centers, mainly to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

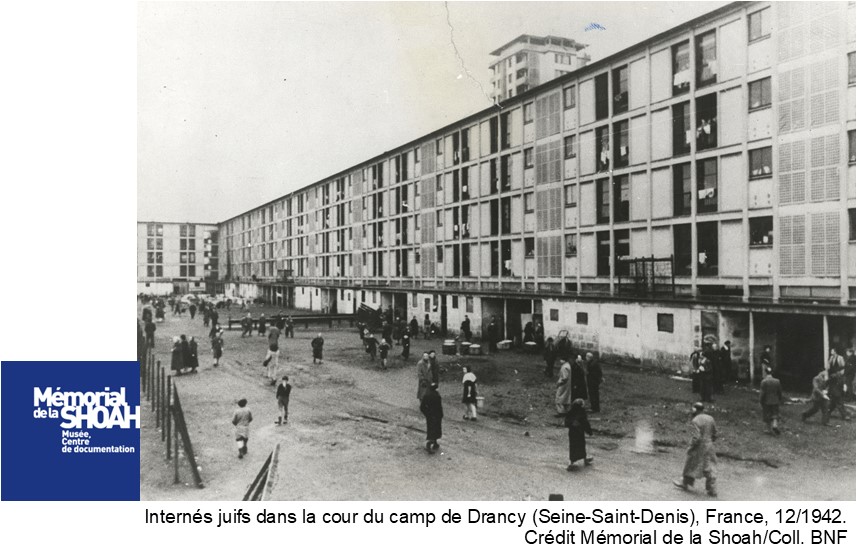

In the second half of 1942, there were large numbers of new arrivals and not enough of anything to go around. During the worst raids in 1942, there were 7,000 people in the camp, even though its maximum capacity was only 5,000. Nine out of ten Jews passed through Drancy camp during the Holocaust.

In early summer 1944, as the Allied troops were advancing, thousands of Jews being held in southern cities were transferred to Drancy to be deported.

The final convoy left Drancy on August 17, 1944. The deportees were marched to the Bobigny train station. The march was led by the Nazi officer Aloïs Brunner, who had taken charge of the camp a year earlier, on June 18, 1943.

The camp was closed in August 1944.

Before they left, the Nazis burned all the camp records so that there would be no evidence of the torture they had inflicted, but two internees from the camp managed to salvage a file containing the names of all the deportees who had passed through the camp.

The camp was then entrusted to the Resistance. On August 20, the remaining internees were liberated.

After the liberation of Paris, from August 19 through 24, 1944, Drancy camp was used as a detention center for people suspected of collaboration, such as the writer and director Sacha Guitry and the singer Germaine Lubin, among others.

Léglise

Gaudin

View of Drancy camp in 1940. Photo credit, Shoah Memorial

View of Drancy camp in 1940. Photo credit, Shoah Memorial

Jewish prisoners in the courtyard of Drancy camp, in December 1942. Photo credit, Shoah Memorial, BNF collection

Drancy today

At present, between 600 and 700 people rent the apartments in the U-shaped building. These were restored for their original purpose at the end of the war.

The Drancy camp has been on the list of protected monuments and sites since May 25, 2001. It was on this day that Catherine Tasca, the French Minister of Culture, signed a decree designating la Cité de la Muette an architectural monument.

In 2009, during renovation work, graffiti was found on some slabs of plaster. It had been engraved or written in pencil, mostly by Jewish internees. The oldest graffiti found dates from August 1941. The writers inscribed their name and the date of their arrival at the camp, and in some cases, later on, they added the date on which they left. The names of some people deported on Convoy 77 were among them.

On September 21, 2012, at the request of the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah, the then President of the Republic, François Hollande, inaugurated the Shoah Memorial in Drancy. Now a permanent, well-documented exhibition, it gives visitors the opportunity to learn about the history of the Cité de la Muette and the central role that Drancy camp played in the deportation of French Jews during the Second World War.

M. Rigaud-Léonce

Simon Stanger’s internment record card from Drancy camp. French national archives, ref. F/9/5731

Simon aboard Convoy 77, heading for Auschwitz

At the age of 33, Simon was deported on Convoy 77 on July 31, 1944.

At the end of this part of his story, it is time for a recap.

Simon was arrested four times between 1941 and 1944.

He was interned in two camps in the Loiret department of France: Beaune-la-Rolande and the Matelotte farm in the Sologne region, from which he escaped.

He was imprisoned twice: at the Saint-Paul Prison and the Montluc Prison, both in Lyon.

He was interned in the free zone at the Rivesaltes camp, near Perpignan, from which he also escaped.

He was interned in Drancy for 28 days.

Convoy 77

The Convoy 77 non-profit organization has compiled a list of 1306 men, women and children who were deported on convoy n° 77.

On July 31, 1944, Convoy 77, the last large convoy to deport Jews from Drancy, left Bobigny station bound for the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center.

982 men and women.

324 children.

The convoy left Drancy by bus. There were 1306 deportees, including more than 300 children. They were taken to the Bobigny railroad station. There, the Jews were loaded into cattle cars.

First of all, there were five stops at towns in France, at Épernay, Châlons-sur-Marne, Bar-Le-Duc, Novéant and Metz.

The convoy continued its journey into Germany, passing through Saarbrucken, Frankfurt am Main, Fulda, Erfurt, Leipzig and finally Dresden.

From there, it crossed the border into Poland and arrived in the town of Gortliz. It then passed through Cosel and Katowice before arriving at the Auschwitz-Birkenau killing center.

The convoy left Drancy, France, on July 31, 1944 and arrived in Auschwitz-Birkenau, Poland, on August 3, 1944.

M. Ndala-Bituala

M. Allimonnier

S. El Hakkouni

B. Lesage

A prisoner in Auschwitz

Deported on July 31, 1944, Simon arrived at Auschwitz on August 3, 1944, as shown in the records provided by the Auschwitz Museum.

The records show also that Simon was selected for admission to the camp.

He was registered as a “prisoner” with the serial number B-3931.

He was listed twice in the records of the camp infirmary for prisoners – on January 5 and 18, 1945 (operating room – block 21, KL Auschwitz I).

He was liberated from the Auschwitz Konzentrationslager (German for concentration camp) on January 27, 1945 by the Soviet army.

He was then sent to a hospital set up by the Polish Red Cross in the grounds of the liberated camp.

The final entry in the records is that he was released from Auschwitz and liberated on March 9, 1945.

Auschwitz I

Before the war

Oswiecim, which is about 45 miles from Krakow in Poland, was renamed Auschwitz in 1939 after Germany invaded Poland.

In the late 1930s, it was home to 7,000 to 8,000 Jews out of a total population of 12,000.

It was in this town, in April 1940, that Himmler ordered the construction of the largest of the concentration camps. It was built on the site of a former Polish artillery barracks.

During the war

Auschwitz I was the original concentration camp and administrative headquarters managed by Rudolf Höss from May 1940 to November 1943, then by Arthur Liebehenschel from November 1943 to May 1944 and finally by Richard Baer from May 1944 until the evacuation of the camp in January 1945.

It was a forced labor camp with a surface area of about 15 square miles, divided into several blocks.

The prisoners in the camp were political critics and enemies of the Nazi regime and people regarded as “inferior” by the Nazis: Jews, gypsies, people with disabilities, homosexuals etc. The Nazis used the prisoners to work in their factories.

The living conditions in the camp were abominable: the prisoners were treated cruelly, beaten, insulted and humiliated (for example, when they first arrived, the SS made them strip naked and shaved them all over).

The prisoners were crammed into tiny cells. Each block was intended to hold 400 people, but in reality, there were between 700 and 1000.

The liberation of the Auschwitz camp took place in January 1945. The prisoners who were able to walk were evacuated from January 17 to 21, 1945. The others, who remained in the camp, were liberated by the Red Army on 27 January 1945. It was then that the Soviet troops discovered that a massacre had taken place there.

Auschwitz nowadays

Auschwitz, which is now called Oswiecim again, is a town of 40,000 inhabitants.

The Auschwitz camp has been made into a museum. It is a major historical and cultural monument dedicated to the “duty of remembrance”: to never forget the Holocaus and to pay tribute to all the people who died in this camp.

The museum has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979.

A. Lieblang

O. Ventolini

May 1945 – Simon’s return to France

Simon was repatriated to the Marseille Center in France on May 10, 1945.

As for the detail of his return, we were very fortunate to find a very rare record, a “Carte de Repatrié” (repatriated person’s card), in the Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division file, record n° 21P 677 692.

It was issued to him in Paris on May 20, 1945.

It is an old document that is barely legible, but this is what it says: he was given a suit, a shirt and a handkerchief, and various sums of money, including one in June 1945.

In September 1945, he was convalescing.

He moved to 70, Faubourg Poissonnière and stayed there until October 1, 1945. He then rented an apartment at 40, rue d’Enghien in the 10th district of Paris. He paid a rent of 4647 French francs for this apartment until 1954.

We suppose that he soon resumed his work as a furrier, despite having been diagnosed with respiratory problems when he returned to France.

He actually got back his furrier’s store at 56, Faubourg Poissonnière on September 26, 1947, as shown on the registration form in the trade register (ref. D34U3 2343) and on the corresponding page of the register (ref. D33U3).

Records from the trade register showing that Simon reopened his store in Paris

1961 – Simon was finally granted French citizenship

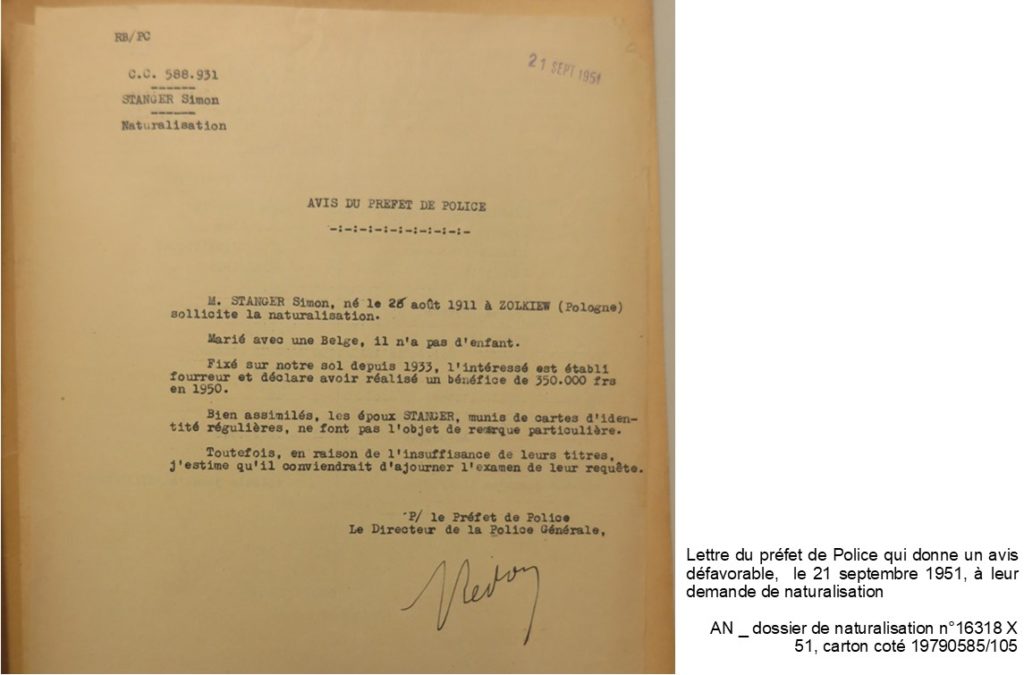

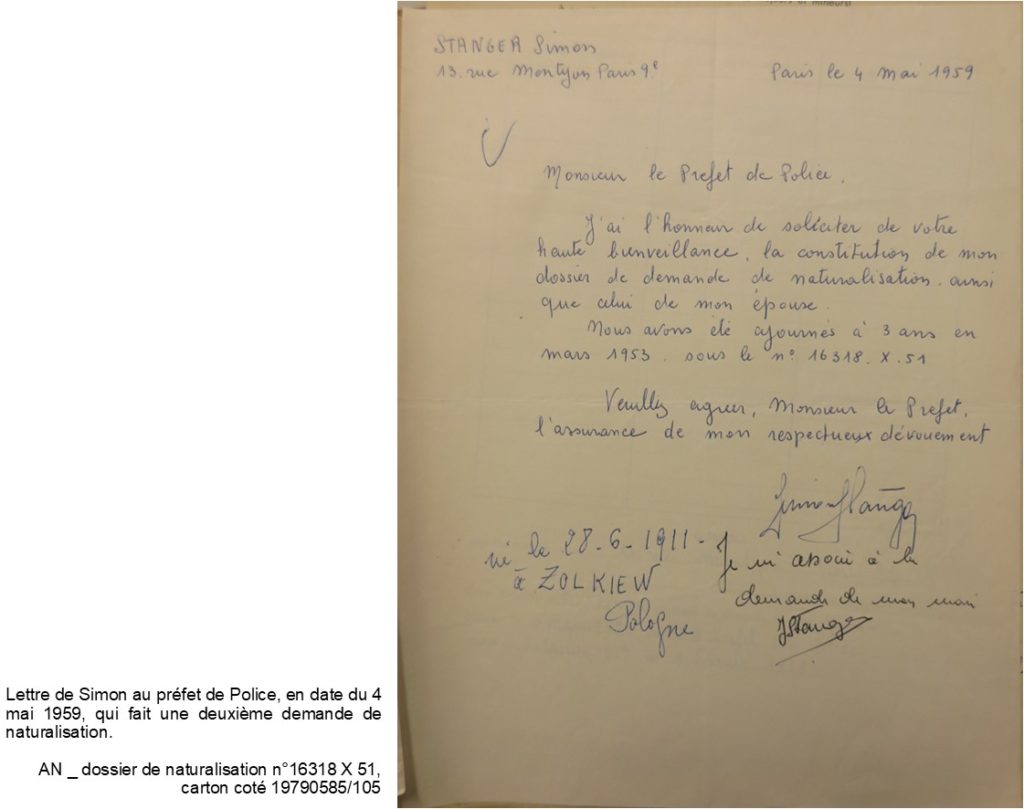

When he returned to France in 1945, Simon began another long journey, an administrative process that involved numerous pitfalls. He applied for French citizenship by naturalization on September 12, 1950, renewed his application in May 1959, and then began a request for the status of “political deportee”, which was granted on July 23, 1957.

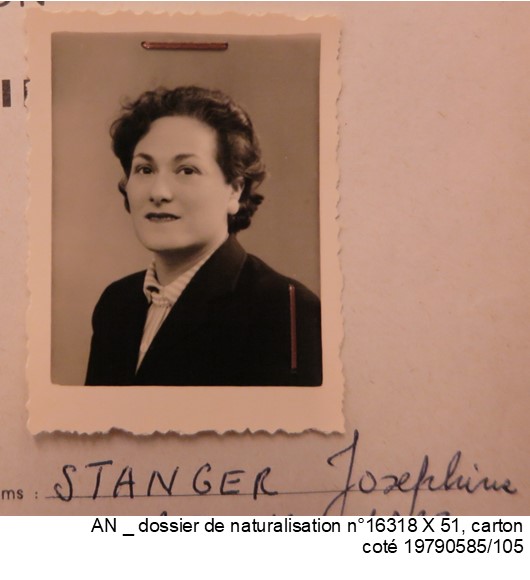

The naturalization application file kindly provided by the French National Archives (number 16318 X 51, in file 19790585/105), for which we would like to thank them, enabled us to find out about his wife, Josephine Stanger, née Horowitz.

They were married on March 15, 1950, in the town hall of the 13th district of Paris.

The file relating to his application for French citizenship by naturalization is ninety pages long.

Simon compiled a dossier in which we can trace his entire journey: the times he was arrested, a recommendation from the Prefect of the Rhone dated March 29, 1951, which “does not oppose a favorable response to the request for naturalization […] if he has acquired […] sufficient credentials to justify this special gesture”. On February 21, 1951, the Paris Chamber of Commerce did not object to Simon Stanger’s naturalization. However, in 1959, we find the following opinion: “Although nothing unfavorable has been revealed about the person concerned, there is no adequate evidence to show in an indisputable way the merits of the applicant for naturalization as a French citizen.”

We see that Simon justified his request for naturalization by explaining that he “wished to settle permanently in France and out of sympathy for France and its institutions”

We see that Simon justified his request for naturalization by explaining that he “wished to settle permanently in France and out of sympathy for France and its institutions”.

He had a clean criminal record and had to prove that he had paid his taxes on time. There is even a report about his integration into French society. Simon Stanger had to appear at the General Police Department where he was questioned about “his lifestyle, his occupations, the circles in which he mixed and his level of education […]”. In conclusion, the report says that Simon Stanger was “integrated through his morals, his frame of mind, his attitudes and [the fact] that he speaks the French language fluently.”

His first application was refused in March 1953, apparently on the grounds that “Simon and Josephine have no children, Simon’s profession is of no national importance, Simon did not attempt to serve in the French ranks during the 1939-1945 hostilities and has no proof of resistance activities, and lastly, they have not provided any proof of loyalty [to France].”

His second request was accepted even though the Prefect of Police had issued a negative assessment on the grounds of his having “insufficient credentials”.

A record in the Paris Archives (ref. D33U3 628) shows that Simon reopened his fur business in 1947. He therefore returned to his former occupation.

In 1950, he employed two French people: Edmond Adler, born in Paris, who lived at 59 rue du Département, Paris 18th, and Fernande Ghiban, also born in Paris, who lived at 27 rue Poissonnière, in the 2nd district.

He was a member of the fur trade union.

Simon declared that he earned 10,000 NF (new French francs) per year.

On October 8, 1961, having been refused for the first time eight years earlier, Simon Stanger appeared in the official French gazette, the Journal Officiel. He was finally naturalized and granted French citizenship.

etters from the Prefect of Police in 1951 and Simon Stanger in 1959, relating to his request for French citizenship.

Source: French National Archives, naturalization file n° 16318 X 51

Joséphine Stanger, née Horowitz

As we investigated the life of Simon Stanger, we also found out about his wife, Josephine Horowitz.

She was born on December 29, 1923, in Antwerp, Belgium.

She was the daughter of Samuel Horowitz, born on January 12, 1896 in Antwerp, and Anna Horowitz, born on June 1, 1897 in Krakow, Poland, both of whom were Belgian citizens.

Her parents were diamond merchants.

Joséphine, known as Josée, had one sister, Stella Horowitz, born on May 8, 1927, also in Antwerp.

The Horowitz family moved to France for work in December 1932. Josephine was 9 years old at the time. Her parents wanted to settle permanently in France.

They moved to Paris, where they lived at 35 rue Victor Masse, in the 9th district, from 1934 to 1937, and then at 55 rue Lamarck, in the 18th district, from 1937 to 1942.

Josephine went high school in France and passed the first part of the baccalaureate. From October 1943 to August 14, 1945, the Horowitz family went into hiding in the free zone, during which time they used the surname Herbier. They stayed in Le Puy, in the Haute-Loire department, most likely at 55, boulevard Carnot. Josephine’s father was arrested in the Puy-de-Dôme department. He was transferred from the free zone to Drancy and then deported on Convoy 51 on March 6, 1943. He was imprisoned in the Sobibor camp, from which he never returned.

Back in the Paris area, Joséphine, along with her mother and sister, moved to Allee des Platanes in Suresnes until 1947, when they moved back to the 18th district of Paris. Their last known family address was 22 rue Francoeur, in the 18th district. Joséphine then met Simon and the two of them moved to 40 rue d’Enghien, in the 10th district of Paris, until 1954; then to 13 rue Monthyon, in the 9th district, and finally to 36 rue d’Hauteville, in the 10th district, where they lived until 1977.

Joséphine did not go out to work after she got married. We note in the file that from July 1949 to March 1950, she was an secretary/assistant to the dental surgeon M. Burgos, at 5, rue du Bac in Suresnes.

Josephine’s sister was a student when Simon and his wife filed their first application for French citizenship by naturalization. When they made their second application, Stella was married to a dental surgeon, Abraham Kranceblum. She became French by marriage.

Photos of Joséphine from the applications for French citizenship.

Source: French National Archives, file n° 16318 X 51

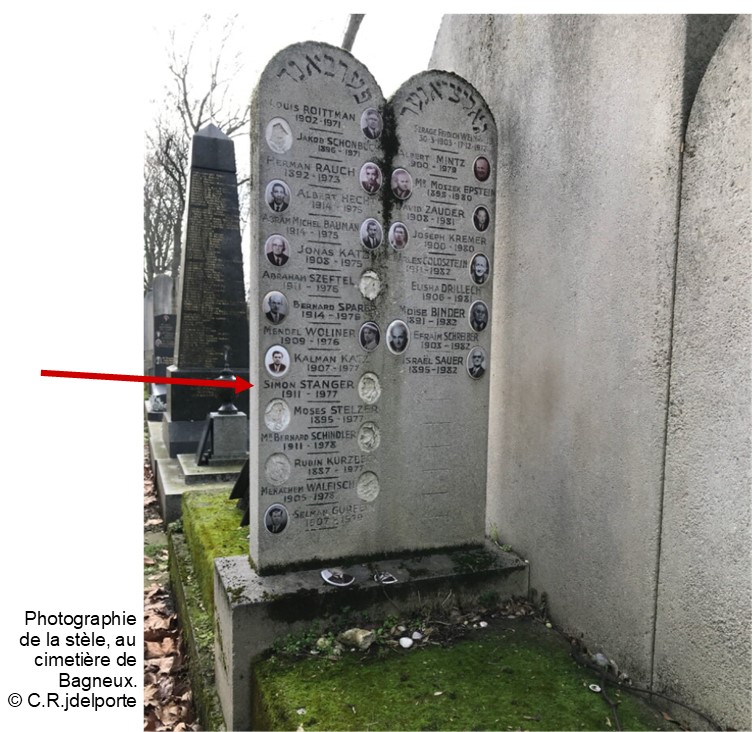

Simon, buried in Bagneux cemetery

After much research into Simon’s life after he returned to Paris, we finally found a trace of him at the end of his life.

First of all, thanks to L. Klejman, our research led us to the Bagneux cemetery.

We discovered that Simon Stanger was buried in Bagneux in a communal grave, along with other people of Jewish origin. The dates on the headstone match: Simon Stanger, 1911-1977.

The staff at the Bagneux cemetery agreed to do a search for us, but to no avail. We were unable to find out why Simon is buried there, let alone the reason for the communal burial.

Finally, after much research and many requests, we received a copy of Simon Stanger’s death certificate by mail to the school.

Simon Stanger, husband of Josephine Horowitz, died on March 23, 1977, at 2:30 p.m. in his home at 36, rue d’Hauteville.

“The death certificate was drawn up on March 24, 1977 at 9:00 a.m., based on the declaration of Isaak Scheuernan, representative, residing in Paris 19th district, at 6, Square Simon Bolivar, who read the certificate and was asked to read it, and signed it with us.”

In memory of Simon

Photo of the headstone bearing the name Simon Stanger at Bagneux cemetery

Link to our journal (in French) about Simon’s life

https://fr.calameo.com/read/006788130c2f24ccab880

Français

Français Polski

Polski