Eliette MEYER (1904-1944)

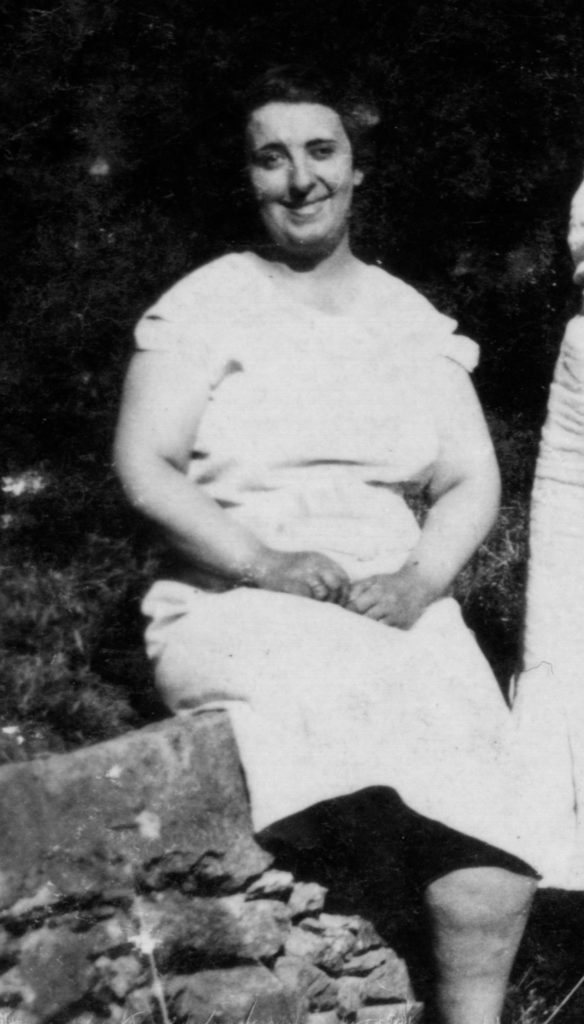

Eliette Meyer ©Claude Bloch family archives

As part of the Devoir de Mémoire (“Duty to Remember”) project that has been running for several years at the Alexis-Kandelaft junior high school in Chazay-d’Azergues, in the Rhône department of France, we, Blandine Renard and Olivier Charnay, history and literature teachers, chose to work with some 9th grade students to research and write Eliette Meyer’s biography. We also wanted to reconstruct her life in a different way, in the form of a video documentary.

This work, which began in early April 2020, in the middle of the coronarvirus lockdown, was carried out with the students thanks to the digital resources made available to allow teaching to continue. The students were also assisted by Séverine Koprivnik, cultural coordinator at the Montluc Prison National Memorial Center.

This idea of reconstructing Eliette Mayer’s life was developed jointly with Philippe Perron, director and producer at CANOPE Lyon: to film and have filmed the very creation of this biography during this most unusual period of lockdown. The idea here was not to put ourselves in the spotlight, but rather to read and watch how the students’ work helped to reconstruct Eliette Meyer’s life story in the best way possible.

Claude Bloch, her son, a Holocaust survivor, agreed to testify in June 2020 during an interview filmed at the Montluc Prison National Memorial Center.

The video version of this biography, as well as the interview with Claude Bloch, both in French, are available on the Memento channel on the Academy of Lyon’s streaming video service:

The biography can be found here

And the Interview here

Eliette Meyer (1904-1944)

The biography below contains a selection of documents illustrating selected events in Eliette Mayer’s life, but a complete list of sources is available at the end.

Lyon: Childhood and family life

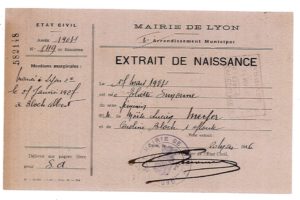

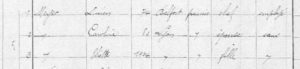

Eliette Simonne Meyer was born on March 17, 1904 at 46, rue Franklin in the 2nd district of Lyon. She was the daughter of Lucien Moïse Meyer, born on November 9, 1874 in Belfort, and Caroline Bloch, born on January 28, 1878 in Lyon, who, since her marriage on December 16, 1901, had chosen to use her husband’s surname.

Eliette Meyer birth certificate, ©SHD/PAVCC 21 P 516 025

Eliette, who was an only child, spent her entire childhood with her parents in the 2nd district of Lyon. She was about ten years old when the family moved to rue Sainte Hélène. Her wider family also included an aunt and a first cousin, her father’s sister and niece, and an uncle, her mother’s brother.

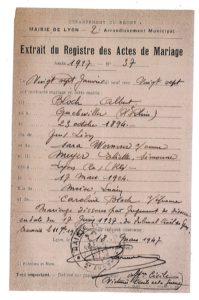

Eliette and Albert’s marriage certificate ©SHD/PAVCC 21 P 516 025

On January 27, 1927, Eliette married Albert Bloch, born on October 23, 1894 in Guebwiller, and thus changed her surname. She moved in with him at 35, quai Gailleton in Lyon.

The couple’s first son was born in 1927, but died a short time later. On November 1, 1928, Eliette gave birth to a second child, Claude Léon Bloch. A third son, born in 1931, died two years later, in 1933.

Eliette often took Claude to play at Place Bellecour, in the center of Lyon, where she would hire a chair and meet up with her friends. As she worked only occasionally, as a secretary in her husband’s store, she had some free time.

On June 17, 1937, ten years after they were married, Eliette divorced Albert and went back to using to her maiden name, Meyer.

She then moved, together with Claude, to a small apartment at 46, rue Franklin. Her parents, meanwhile, lived in a larger apartment at number 44. The following year, in 1938, her son’s father died.

Place Bellecour in the 1940s ©Lyon Municipal library / P0546 SA 16-03

1911 census (46 rue Franklin, Lyon) ©Rhône Departmental Archives, ref. 5 M 530

France at war

On September 3, 1939, France declared war on Germany, which had invaded Poland on September 1. Following a major German offensive on May 10, 1940, French forces were overwhelmed and an armistice was signed with the Reich on June 22, 1940. This stipulated that France would be divided into two areas: the occupied zone in the north and the free zone in the south.

The Vichy regime: antisemitism and collaboration

In France, the Third Republic collapsed on July 10, 1940 and the French state was created. This French State, also called the Vichy Regime, was led by Marshal Pétain and during the Second World War it cooperated with the Nazi regime.

The occupied zone and the free zone, with thanks to Eric Gaba for original blank map and Rama for zones — Personal work, NGDC World Data Bank II

The French state enacted a number of anti-Semitic laws aimed at excluding Jews from society. On October 3, Jews working in the French public service were forced to leave their jobs.

Eliette Meyer, who was at that time working at the Prefecture of the Rhone department, was therefore obliged to look for a new job.

As of June 2, 1941, Jews were obliged to take part in a census and the French authorities compiled registers of their names and addresses, thus facilitating future arrests.

Eliette and her entire family intentionally avoided participating in the census. From then on, the Meyer family, as well as all those who were not counted, were regarded as outlaws.

Round-ups in the region were increasing.

In Lyon, in August 1942, more than 500 Jewish people were arrested and deported, while in Villeurbanne, where Eliette was now working, nearly 300 people were rounded up in March 1943. Meanwhile, Eliette’s first cousin, who had lived in Paris with her family, was in Auvergne where she and her children had sought refuge near the village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon. Her husband, who had stayed in Paris in the occupied zone, was arrested and deported on the first convoy to Auschwitz where he died in March 1942.

It was also in 1942, in November, that Hitler launched operation “Attila” or “Anton”, in response to the Allied landings in North Africa. The Free Zone was invaded and France was now totally occupied. The French authorities also required Jews’ identity cards to be stamped with the word “Jewish”, and this increased anti-Semitism in France even further. The Meyer family lived in constant fear of being discovered. This explains why, on January 1, 1943, they once again broke the law to try to protect themselves. When Claude was 15 years old, his grandfather Lucien Moïse Meyer altered his first identity card by changing his grandson’s last name “Bloch” to “Blachet”, a name with a less Jewish connotation.

Everyday life during the war

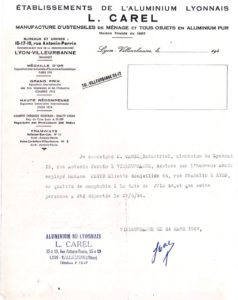

After she had to leave her job in the public sector, Eliette worked as an accountant and secretary for a company called L. Carel, which made saucepans, in Villeurbanne.

Employment certificate from L. Carel, dated June 1944 ©SHD/PAVCC 21 P 516 025

Ever since the start of the war, it had been very difficult to buy food supplies. Ration coupons were needed for almost everything. However, the Meyers found a little village, Saint-Appolinaire, in the Azergues valley, to the northwest of Lyon, where they could trade pots and pans with peasant farmers in exchange for food. L. Carel sold these pans to Eliette about once a month, after much pleading on her part. Eliette and her son were then able to take the train to the village and go around the farms to ask for food. The milkman would drop them off in the village square in the morning and meet them at the end of the day to take them back down to the train station. “It was essential to be on time,” her son Claude Bloch recalls. They also had to avoid the French and German checkpoints.

In February 1944, Eliette’s mother, Caroline, heard that roundups of Jews were about to take place in Lyon. The family therefore decided to leave their apartments in Lyon and rent a three-room apartment from some people who agreed to take them in. It was at 6, chemin de Bellevue in Crépieux-la-Pape, a town in the Ain region that is now part of Rillieux-la-Pape.

They were right to move when they did, because in May 1944, Eliette’s parents’ apartment was raided by the Militia and turned into an office.

It is for this reason that very few family documents (photos, letters, pay slips etc.) still exist.

Claude Bloch has one, and only one, photo of his mother; which was taken before the war.

Eliette Meyer ©Claude Bloch’s family archives

June 29,1944: The arrest

On May 26th, 1944, Allied bombs rained down on Lyon, particularly on the Avenue Berthelot, where the Gestapo had been headquartered since April 1943. They then moved to 32, Place Bellecour. On June 28, 1944, Philippe Henriot, a Vichy collaborator, was assassinated by Resistance fighters. In reprisal, Paul Touvier, head of the Lyon Militia, decided to kill seven Jews in the cemetery at Rillieux, a village near Crépieux-la-Pape, the following day.

On June 29, 1944 at 11:45 a.m., Eliette, her father and her only son Claude, were arrested by French soldiers at their home, 6 chemin de Bellevue in Crépieux-la-Pape. Eliette was on sick leave that day due to kidney problems, while her son Claude was on vacation and repairing his bicycle. Her mother, Caroline, was not there, as she had a dentist appointment and had left early to run some errands.

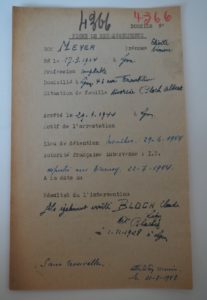

Arrest information record ©Rhône Departmental Archives ref. 3335 W 13

Two men went upstairs to arrest them. One of them laid a pistol on the table and told them to pack their bags. No one tried anything risky because they knew they were in a helpless situation. Eliette asked her son, despite the summer heat, to put on his long pants, which made him look older. Before leaving the house, Lucien asked to go to the bathroom. There were two identical doors: one to the washroom and the other leading to the basement, which led to the outside. According to Claude Bloch, his grandfather hesitated for a split second. He could have got away if he had run very fast, but his daughter and grandson were still there and they risked having to pay the price for his escape. He therefore only went to the bathroom, and in doing so, he condemned himself in order to save the lives of his loved ones.

After the war, the owner of the house, Mr. Billard, and a neighbor, Mr. Giraudet, bore witness to the arrest of the family, referring to the French Popular Party (P.P.F.). According to Eliette’s son, who was able to identify him from photos, the arrest was carried out by Paul Touvier, head of the French Militia in Lyon.

Internment in Montluc and then in Drancy

After they were arrested, Eliette, Lucien and Claude were transferred in a Renault Juvaquatre vehicle to the Gestapo headquarters at Place Bellecour in Lyon.

A recent photo of the building used as the Gestapo headquarters on Place Bellecour © Rhône Departmental Archives, ref. 4544 W 23

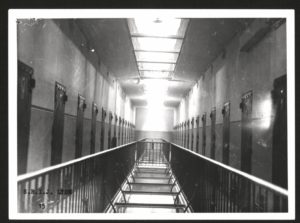

Eliette and her father were separated from Claude for questioning. Lucien did not survive the interrogation. When Eliette was taken back to the basement where her son was being held, she had just enough time to whisper in his ear “they killed your grandfather”. Moments later, he saw a man carrying Lucien’s body away. That evening, Eliette and Claude were taken to the Montluc prison and spent the night together in a cell.

Cells in Montluc Prison, in Lyon ©Rhône Departmental Archives, ref. 4544 W 17

They were separated again the following day; Claude was sent to the “barracks for the Jews” and Eliette remained in her cell, along with seven or eight other people.

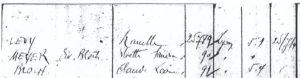

It was almost a month later, on July 20, 1944, that Eliette and her son were summoned to come out of their respective cells “with luggage”. They were then taken by bus to Perrache station in Lyon where they boarded a train for a destination that was as yet unknown to them. Men and women travelled in separate cars. After a stopover in Dijon on July 21, Eliette and her son arrived the next day at Bobigny train station, near the Drancy transit camp. They were registered in the camp on July 25. They were both put in the same building, where they stayed together for a little over a week.

Drancy Camp arrivals log, French National Archives

Convoy 77

On July 31, Eliette and her son left Drancy on Convoy N°77. They were among the 986 men and women, and 324 children, who were deported on the last of the large convoys to leave Drancy for Auschwitz (figures supplied by the Convoy 77 association).

She traveled with Claude, for three long days, in a cattle car. Deprived of food and water, they stood with about 80 other people, while on the outside of the wagons it was written “Men 40, Horses longways 8”. They arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on August 3, in the early hours of the morning, when it was still dark. The deportees were separated into two lines, women and children on one side and men on the other. Eliette headed towards the first line, but when her son began to follow her, she pushed him back to the men’s line. Despite his young age, his long pants made him look like more like a man than a child. It was the last time Claude was to see his mother. Eliette died at the age of 40.

What happened to Eliette Meyer next is not clear. During the evacuation and winding-down of the Auschwitz site by the camp authorities, many important documents were destroyed.

Her son feels it very likely that she was killed in the gas chambers as soon as she arrived at the camp because her white hair, which had not been colored for several weeks, made her look older. He also told us that he hopes that his mother was indeed gassed soon after arrival and that she did not have to endure long months of suffering in the camps “to achieve the same result”.

Post-war recognition

Claude Bloch returned from deportation in July 1945 and was reunited with his grandmother.

The Meyer-Bloch family tree, by Margaux Chevaleyre, Chazay d’Azergues junior high school

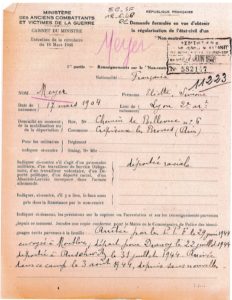

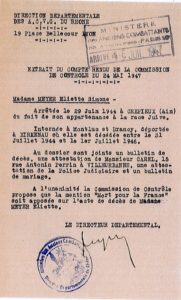

Claude took the necessary steps to have his mother declared dead and, some years later, filed a complaint against Paul Touvier, the militiaman who was allegedly behind their arrest. As a result of his efforts, Eliette was initially registered as “not having returned” from Birkenau on May 20, 1946.

Request for official recognition as a “Non-returnee” ©SHD/PAVCC 21 P 516 025

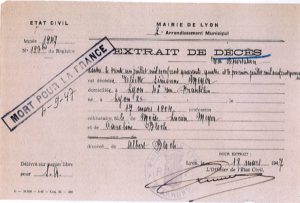

Next, the Civil Registry of Deportees office declared Eliette missing on September 6 of the same year. Her death certificate was finallyissued at Lyon City Hall on March 17, 1947. It states that Eliette died between July 31, 1944 and July 1, 1946.

Death certificate issued in 1947 ©SHD/PAVCC 21 P 516 025

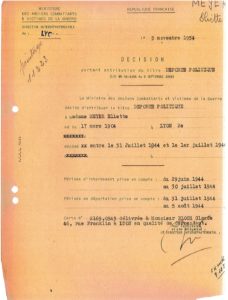

The authorities thus collected together all of the evidence showing that Eliette Meyer was arrested on racial grounds, because she was Jewish. As a French citizen, she was thus recognized as “Morte pour la France”, or having “Died for France” and this was noted on her death certificate on September 4, 1947. In 1954, she was finally acknowledged as having been a “political deportee”, i.e., a civilian victim of the war.

“Died for France” certificate ©SHD/PAVCC 21 P 516 025

“Political deportee” certificate ©SHD/PAVCC 21 P 516 025

That same year, Claude Bloch, her son, received 12,000 francs from the government, a sum that his mother, as a victim, would have received had she lived.

Upon returning to the scene of their arrest in the 1990s, Claude learned from his former landlord’s daughter that they had surely been turned in.

Lucien Moïse Meyer’s death certificate was issued on June 26, 1947, and he also received the distinction “Died for France”. Finally, by a decree dated July 3, 1995, Eliette was granted the distinction “Died during deportation” and this too was added to her death certificate.

The Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris ©Shoah Memorial

Our conclusion:

Our teachers suggested that we write this biography in the difficult context of the spring 2020 lockdown. We had just completed our second project of the year on the Duty to Remember and this idea made sense to us immediately. We carried out the whole project during the lockdown, each of us in our own home and yet all of us together, and we coordinated our research and work through weekly video-conferences.

A video conference on Zoom, during the lockdown

We had the chance to meet with Claude Bloch to help us complete our project. We would like to thank him very warmly for the trust he put in us by passing on his family memories and the story of his mother, who he last saw when he was our age. How can we not imagine ourselves in his position, as an adolescent growing up without his mother?

Photo of Claude Bloch, taken at the Montluc Prison National Memorial Museum in June 2020

It seems to us that it is our responsibility as future citizens to keep the memory of the Holocaust alive and, in our turn, to pass it on. It is important to understand that education about the Holocaust must not be limited to history lessons. With our newfound voices, using social media and other means of communication, we must keep this memory alive.

We would therefore like to thank our teachers, Blandine Renard and Olivier Charnay, cultural facilitator Séverine Koprivnik, film director Philippe Perron and history student Blanche Renard, as well as all the other people who have contributed their time and energy to our work..

Chloé, Clément, Fiona, Jérémie, Margaux, Maellys, Candice, David, Isabelle, Juliette

- Kandelaft junior high school

28 June, 2020

Notes and overview of sources available

for biographical research into the life of Eliette Meyer

The victim’s status

In order to define the victim’s status, we look at the ways in which he or she was a victim (imprisonment, deportation etc.) and whether or not he or she was a part of the resistance movement.

– If the person was just imprisoned, he or she is described as an “internee”.

– If the person was deported, we describe them as a “deportee”.

– If the person was involved in combatting the enemy, we note « military » or « resistant »

– If the person was not involved in fighting or resisting, for example if they were arrested as a hostage or because they were Jewish, we note “civilian” or “political”.

We therefore come across files on ” political internees”, “resistant internees”, “political deportees”, “resistant deportees”, etc., which include evidence to show what these people were subjected to in order to be officially recognized as victims. Resistance fighters or families of resistance fighters received more assistance than “political” (civilian) victims.

In addition, for someone who was part of the resistance movement, nationality was irrelevant, whereas for a political (civilian) victim, it had to be proven that the person was a French citizen.

Victims’ rights

Being a victim entitled the person to receive financial assistance and gave them certain rights. If the person was deceased, their family dealt with the necessary formalities and put together the documents needed to have the person recognized as “Mort pour la France”, or “Died for France”. This entitled their children or parents to receive State aid as a “rightful claimant”. If the victim or their family did not take all the necessary steps, it is often difficult to locate information.

Rejected applications

– People who were imprisoned or deported after having been arrested for a civil offense (theft or other crimes not related to the resistance) were not eligible for victim status.

– People who were civilian (political) victims but who were not French citizens were also ineligible.

– People were refused resistance member status or military status if there was insufficient evidence.

Eliette Meyer was recognized as a “political deportee” and as having “Died for France”.

Lucien Moïse Meyer was recognized as a “political internee” and as having “Died for France”.

Claude Bloch was recognized as a “political deportee”.

1. Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division of the Ministry of Defense Historical Service, in Caen. (série 21 P)

The French Ministry of the Armed Forces has various records offices known as the Service Historique de la Défense (SHD), or Historical Defense Service, which are organized by theme. The SHD holds both its own archives and also those of the former “Ministère des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre” or “Ministry of Veterans and War Victims”. This is now part of the Ministry of the Armed Forces and is called the Office National des Anciens Combattants et Victimes de Guerre (ONACVG), or National Office of Veterans and War Victims. Its records are now held mainly in Caen, in Normandy, at the Historical Defense Service, Victims of Contemporary Conflicts Archives Division (or Pôle, in French)

These files contain information on the investigation into whether the living or deceased victim or their family was entitled to receive State assistance. They therefore include a wealth of interesting material. The files show whether there was sufficient evidence for a person to be recognized as a war victim and whether the person “Died for France”.

2. The Rhône Departmental Archives and the Lyon Metropolitan Archives (3335 W)

These documents, from the “Fonds Montluc” (Montluc collection), originally belonged to the judicial police, who carried out a major post-war investigation to trace the victims that the Germans had incarcerated in Montluc prison in 1943 and 1944. They also gathered together evidence found in German archives, the archives of the Vichy regime and witness statements etc.

There are only two documents relating to Eliette Meyer:

– a small note with just her name, date of arrest and a file number. This document was produced by the police to identify the file. At that time, when there were no computers, such cards were filed in small boxes, sorted either by number or in alphabetical order.

– another document that the police found in the Vichy regime’s archives, to which they then added further notes. At that time, when a person was arrested by the Germans and the Vichy regime became aware of it, a card was created with the person’s details (written in black). Then, the “IP”, the Vichy Police Intendant, got involved and asked the Germans for an interpreter to find out what had happened to the person in question. As a result, the Vichy regime knew that Eliette Meyer had been imprisoned in Montluc and had left for Drancy on 22-7-1944. The post-war police noted the result of their investigation at the bottom of the sheet: “sans nouvelles”, or “no further news”. Finally, they gave an official document to the family: “attestation remise le 31-8-48“, or “attestation issued on 31-8-48”.

3. Yad Vashem – The World Holocaust Remembrance Center

This record comes from the Yad Vashem Memorial, a Jerusalem-based center for documentation, research and education. In particular, it produces pages of witness accounts from all over the world about Jewish people who were murdered during the Second World War.

The information noted on Eliette’s page matches the account of Claude Bloch (the witness mentioned at the foot of the document) about his mother. Please note, however, that some witnesses were not direct witnesses to the events or descendants of the victims.

https://yvng.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=en

4. The Documentation Center for the Deportation of Jewish Children from Lyon (CDDEJ, Le Centre de Documentation sur la Déportation des Enfants Juifs de Lyon)

This association was founded during Klaus Barbie’s trial in Lyon in 1987. It assembles a large number of archives, particularly from schools and town halls, about the children’s lives. Its aim is to make this information available to students, teachers and historians.

A document from La Martinière, where Claude Bloch went to school during the war, mentions his mother’s name.

https://www.deportesdelyon.fr/le-cddej

5. The Shoah Memorial in Paris

These archives were mostly gathered at the request of Isaac Schneersohn, an industrialist who set up a secret archive collection during the war. The objective was to gather evidence of the persecution of the Jews in order to bear witness and seek justice at the end of the war.

There is a record of Eliette Meyer’s stay at Drancy camp (the search log when she first arrived) and her name is on the list of deportees on Convoy 77, as is that of her son, Claude Bloch. Her name is also inscribed on the “Wall of Names” at the Shoah Memorial.

http://www.memorialdelashoah.org/archives-et-documentation/quest-ce-que-la-shoah.html

6. The National Memorial Museum at Montluc prison

The museum has a biographical panel about Eliette Meyer, produced in 2013.

http://www.memorial-montluc.fr/

Summary of the work published by Professor Charlotte Bonnet on October 5, 2020

We are pleased to share with you all the work done in recent weeks, as well as the preliminary work done during the lockdown, on the biography of a deportee, Eliette Meyer, on the Convoy 77 website. Some of us had the opportunity to participate in a Zoom meeting at the end of August, and since then we have been working to ensure that this multi-stakeholder school project is published and that the memory of the Holocaust continues to be passed on using electronic media.

- First of all, the biography researched and written by the students, with the support of their teachers, Blandine Renard and Olivier Charnay, and the cultural facilitator at the National Memorial Museum at Montluc prison, Séverine Koprivnik:

- Next, the film directed by Philippe Perron, of the Canopé network, in partnership with Olivier Charnay of the DRANE de Lyon, available on the Memento channel of the DRANE of the Academy of Lyon:

- In addition, at the same time, the the witness account of Mr. Claude Bloch, Eliette Meyer’s son, National Memorial Museum at Montluc prison, during which the students were able to interact with him:

- We also provide links to the articles published by students and participants, particularly those of France 3 Rhône-Alpes and the interview with RCF Lyon:

France 3 (the video report is at the end of the article):

RCF Lyon :

The newspapers Progrès Lyon and Patriote Beaujolais:

- Finally, we have registered this project in the États Généraux du Numérique, [a French government initiative to encourage the use of digital media in education] because we believe that what has been achieved using all the digital means at our disposal can be a source of ideas for our contemporaries, for the purposes of passing on history and memory and as demonstration of our experience to help with future work with students:

We sincerely thank you for the support given to us, from near and far, which has enabled us to bring this project to fruition. It remains anchored in the minds of our students, whom we see regularly, and who pass on their work to their high school teachers, friends, acquaintances, etc. through social networks or word of mouth.

We intend to continue this work of memory in the coming years and we hope to have you by our side again!

Please accept our most sincere thanks.

On behalf of Blandine Renard, Olivier Charnay, Séverine Koprivnik and Philippe Perron

Kind regards

Nathalie BONNET

Image library

Contributor(s)

The Alexis Kandelaft junior high school at Chazay d’Azergues in the Rhone department of France, Blandine Renard and Olivier Charnay, history and literature teachers and the 9the grade students/

References

- Video biography

- Interview with Claude Bloch in June 2020

Links

- https://tube.ac-lyon.fr/videos/watch/f1bccd89-d12a-4a42-898f-a3412900ebf4

- https://tube.ac-lyon.fr/videos/watch/06d2fde5-0c2b-458d-a21f-826e171cd751

Français

Français Polski

Polski

[…] Alexis Kandelaft à Chazay d’Azergues, dans le Rhône, ont travaillé sur la biographie d’Eliette Meyer, assassinée à Auschwitz à l’âge de 40 ans. Ce travail fait partie des onze projets […]